3 Current context

neurological rehabilitation and neurological physiotherapy

Introduction

Neurological conditions are those conditions which affect parts of the nervous system. The causes of these conditions are varied and may include trauma, vascular disruption, infection, tumour or degeneration of the nervous system. Conditions may affect the central nervous system, consisting of the brain and spinal cord, or the peripheral nervous system, consisting of the peripheral nerves (Table 3.1). Neurological conditions are often complex, and people with these conditions may require support from many different services. Acupuncture may provide benefits for people with neurological conditions, but it represents just one possible option among many. An awareness of the important aspects of a comprehensive service for people with neurological conditions is important. This chapter aims to outline the various components that are required for effective management of people with neurological conditions.

| Central nervous system | Peripheral nervous system |

|---|---|

Prevalence and incidence of neurological conditions

Neurological conditions are common. Around 10 million people in the UK live with a neurological condition which substantially affects their life [1]. Stroke is by far the commonest neurological condition. Each year, around 125 000 people in the UK, 700 000 in the USA and 1 million in the European Union have a stroke [2]. In the UK, of those individuals with neurological conditions, around 350 000 require help for most of their daily activities, and over 1 million require assistance with some daily tasks [1]. Each year 1% of the UK population are newly diagnosed with a neurological condition and 19% of hospital admissions are for a neurological problem requiring treatment from a neurologist or neurosurgeon [1].

Models of health care

Medical model

The medical model assumes that all illnesses are explained by disease and that the treatment of disease will restore the individual to health [3]. This model was originally developed in the late 19th and early 20th centuries following the scientific discoveries of infectious disease by Pasteur and cellular pathology by Virchow [4]. The medical model is based on reductionism and a dualistic notion of the mind and body. It evaluates individuals in isolation from their environment and takes no account of the social, psychological or behavioural aspects of illness or the patient’s experience of that illness [5, 6]. It was originally developed for the management of severe medical conditions. In these situations treatment of the disease may indeed result in substantial improvements in health. However, with the growing prevalence of chronic disease, the inadequacies of this model are highlighted. The model cannot explain symptoms for which there is no underlying pathology. It also fails to appreciate the complex interaction of social, psychological and environmental factors and their impact on the overall experience of illness by the individual.

Biopsychosocial model

The biopsychosocial model considers individuals as well as their health problem and the social context. It recognizes that health, disease, illness and disability result from complex interactions of biological, emotional, cognitive, social and environmental factors. It recognizes that psychological and social factors influence the person’s perceptions and actions, and therefore the experience of illness. This model suggests that effective treatment of the disease may not automatically result in the resolution of illness and disability. This model has been adopted by the World Health Organization as the basis for the International Classification of Function (ICF) [7].

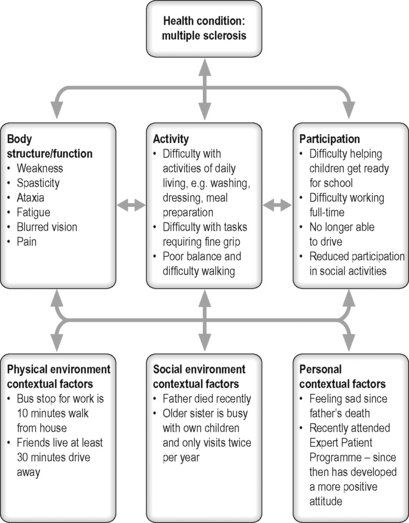

Presentation of neurological conditions and ICF

Neurological conditions may result in a wide range of difficulties. These may include problems with physical ability, sensation, cognition, communication, behaviour and psychological functioning. The ICF developed by the World Health Organization [7] provides a useful framework to classify the consequences of disease (Figure 3.1) [8]. It is based on the biopsychosocial model of disability and supports the consideration of an individual’s situation within the context of biological factors and also the social and physical environment.

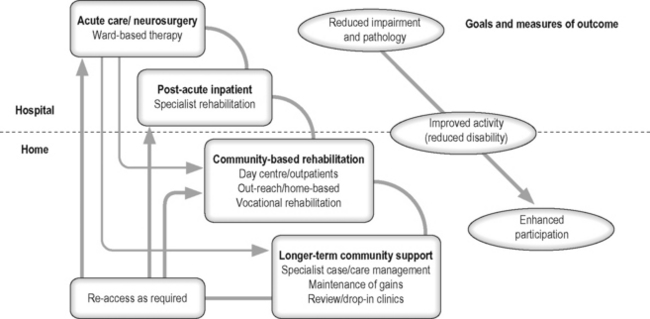

General principles of rehabilitation

Rehabilitation has been defined as: ‘the use of all means aimed at reducing the impact of disabling and handicapping conditions and at enabling people with disabilities to achieve optimal social integration’ [10]. Rehabilitation is a continuous and coordinated process which starts at the onset of an illness or injury and aims to support individuals to achieve roles in society consistent with their aspirations [8]. Many individuals with neurological conditions will require access to rehabilitation services. Support needs to be provided for individuals throughout their life. Clear mechanisms for individuals to re-access relevant services are required (Figure 3.2). In addition palliative care is required to support individuals coming to the end of their lives [11].

Key aspects of effective rehabilitation

Person-centred service

The person should be at the centre of the service provided. Individuals should be provided with sufficient information about treatment options to allow them to be actively involved in all decisions regarding their management [9]. Information provided needs to take account of any communication difficulties that the individual may have. Attention should be paid to the person’s emotional needs as well as practical needs. Support should also be provided to family members and carers [9].

Specialist multidisciplinary team

Access to a coordinated specialist rehabilitation team is an important factor in effective management of the wide range of difficulties an individual may report [12, 13]. The specialist team members should include a doctor, nurse, physiotherapist, occupational therapist, speech and language therapist, clinical psychologist and social worker. Access to the expertise of other services is also important. Such services include dietetics, continence advisory service, orthotics, chiropody, pain management and spasticity management services, ophthalmology and liaison psychiatry.

Goal-setting

Goal-setting is an integral part of rehabilitation and allows the person and the specialist team to focus on key aspects identified as important by the individual [14]. Goals are specific time-bound measurable outcomes relating to a desired or expected future state. Goals are set by the individual, with support from the relevant team members. They guide and inform therapy, as well as providing a structure for the individual regarding future targeted outcomes [15]. Goals need to be challenging but achievable and include long-term (weeks/months) and short-term goals (days/weeks) [12].

Outcome measures

Outcome measures provide information regarding the outcome for an individual following rehabilitation. The use of validated standardized outcome measures is required within rehabilitation services to provide information on individual outcomes, as well as to allow service evaluation [16]. A wide range of outcomes measures have been validated, and they include those that reflect the perspective of the person as well as the clinician [17].

Evidence-based practice

Management programmes for people with neurological conditions need to be based on best available evidence. Evidence-based practice involves the integration of individual clinical expertise with the findings from the best available research [18]. A range of clinical guidelines have been developed to support improved care of people with conditions such as stroke or multiple sclerosis. Guidelines have been based on an extensive review of available research evidence combined with expert opinion [12, 13, 19, 20].

Chronic disease management

Chronic disease

Chronic diseases are diseases of long duration and usually slow progress. They are the leading cause of death and disability worldwide [21]. Many neurological conditions are chronic diseases requiring management over time. These diseases often have a range of persistent symptoms with no cure and the potential for significant impact on the individual’s quality of life [22]. Successful management requires an effective collaboration between the person and relevant health and social care professionals.

The ‘expert patient’

Over time individuals with chronic conditions develop considerable knowledge and experience about their condition and how it affects their life. This expertise has not always been utilized fully within management decisions. There is now a shift in emphasis to support these individuals to be key decision-makers in collaboration with health care professionals [23]. Self-management programmes are supporting this process of the development of ‘expert patients’ [24].

Chronic disease self-management programmes

Self-management programmes aim to equip people with chronic diseases with the skills to manage problems that they frequently encounter. These programmes have been developed over the last 20 years and are delivered in countries across the globe [21]. Many programmes are generic whilst some are specific to a particular chronic condition. The programmes are led by teams of trained volunteers all living with a long-term condition. Evidence indicates that these programmes can help to reduce severity of symptoms, improve life control and resourcefulness, and improve activity levels and life satisfaction [24]. The programmes aim to support people to develop the following skills:

An important aspect of the programme is to enhance the individual’s perceived self-efficacy. Self-efficacy denotes confidence in one’s ability to accomplish a particular goal. Evidence shows that those with higher levels of self-efficacy are more effective in managing their condition [25].

Health and clinical governance

Health governance is a global concept which relates to the actions and means by which a society organizes itself for the promotion and protection of the health of its population [26]. In the UK this has been labelled ‘clinical governance’ and defined as ‘a framework through which National Health Service organizations are accountable for continuously improving the quality of their services and safeguarding high standards of care by creating an environment in which excellence in clinical care will flourish’ [27]. It was introduced as part of health service reform and aimed to address inequalities in quality of service provision across the country. An intrinsic aspect of clinical governance is the establishment of clinical standards against which performance can be measured. Clinical guidelines for people with neurological conditions have been developed, such as those relating to stroke, Parkinson’s disease, multiple sclerosis, motor neurone disease and acquired brain injury [12, 13, 19, 20, 28, 29].

Consent and capacity

Patients must consent to treatments that they receive. Valid consent will depend upon the individual having the capacity to make a decision, as well as ensuring they are not acting under duress. In addition they must have received sufficient information about the intended benefits and possible risks of the proposed procedure [30]. The Mental Capacity Act 2005 for England and Wales came fully into force in October 2007. This provides a statutory framework to empower and protect any person who may lack capacity [31]. Every individual is presumed to have capacity unless it is proved otherwise. People with brain injury or disease may have impaired capacity and therefore may be unable to consent. When patients do lack capacity, any acts or decisions made under the Act on their behalf must be carried out in their best interests.

Key principles of neurological physiotherapy

The physiotherapist is an important member of the multidisciplinary team supporting people with neurological conditions. Physiotherapy is defined as a ‘health-care profession concerned with human function and movement and maximizing potential. It uses physical approaches to promote, maintain and restore physical, psychological and social well-being, taking account of variations in health status’ [32]. Physiotherapy input follows the general principles of rehabilitation outlined earlier, such as using a person-centred approach, use of goals and outcome measurement and the principles of chronic disease management.

Historical development of neurological physiotherapy

Neurological physiotherapy has undergone substantial changes over the past century. During the first half of the 20th century, treatments focused on individual muscle strengthening, bracing or surgery [33]. New treatment methods emerged during the 1950s and 1960s. These were based on the understanding of neurophysiology at that time, and assumed that abnormal movement patterns could be changed by applying afferent stimulation [34]. These ‘neurofacilitation’ approaches were developed by Rood (1956), Kabat (1961), the Bobaths (1965), Brunnstrom (1966) and Knott and Voss (1968). More recently, approaches based on insights from the fields of motor control and learning, biomechanics, muscle biology, brain imaging and cognitive psychology have been developed [34–37].

Physiotherapy within the multidisciplinary team

Physiotherapists work closely with other members of the multidisciplinary team. The physiotherapist’s particular expertise lies within the assessment, analysis and treatment of movement disorders, which are limiting the function of the individual [34]. The physiotherapist will also liaise with colleagues to gain additional information, such as information from the speech and language therapist on the person’s ability to understand language, as well as information from the occupational therapist and psychologist regarding the person’s cognitive ability and emotional status.

Neurological physiotherapy assessment

Body structure/function

Assessment may include evaluation of sensation, proprioception, muscle function, including ability to activate muscles, sustain activation of muscles and coordinate movements, muscle power, muscle tone, including presence of hypotonia, spasticity, dystonia, athetosis, chorea, rigidity, tremor and ataxia, flexibility of joints and muscles, praxis, perceptual ability and cardiorespiratory fitness [34]. Additional assessments may include review of visual and vestibular systems [38] and neurodynamics [39]. Problematic symptoms such as pain or fatigue will also be evaluated.

Interventions

Interventions will be determined by the stated aims of the person in conjunction with findings on assessment. Broad categories of interventions are outlined in Figure 3.3 and discussed below. Interventions will be modified when required to ensure effective participation by those individuals with cognitive, communicative or behavioural difficulties.

Influence sensorimotor system

People with neurological conditions may present with a wide range of different sensory and motor impairments which compromise functional ability [34]. Key principles of treatment will be to maximize remaining functional ability and to minimize secondary complications [40, 41]. Important therapeutic options will now be outlined.

Maximize functional ability

Movement is an essential component of functional ability and is therefore a prime target for intervention [34]. Treatments will be task-oriented and broadly aimed towards enhancing sensorimotor control as a basis for improved posture, balance and mobility including walking, upper-limb function and orofacial function [42–44]. Treatments aim to help individuals achieve their goals and may include intensive task-specific training, for example, treadmill training or constraint-induced movement therapy [34, 40, 44, 45]. In addition, interventions such as muscle strengthening and aerobic conditioning will be utilized as required [42]. The individual will be encouraged to participate actively throughout the rehabilitation process.

Minimize secondary complications

Complications such as adaptive shortening of muscles may occur secondary to primary impairments such as weakness [46]. These secondary complications may have a profound effect on the individual and need to be minimized as far as possible. Those individuals with complex and severe disability may require effective postural management over the 24-hour period, including comfortable but supported sleeping postures and customized support within their wheelchair [41, 47]. Those who are more able may benefit from targeted activity and stretch of ‘at-risk’ muscles such as gastrocnemius and soleus [40]. Passive muscle length may be improved by serial casting [48]. Spasticity may be problematic for some individuals and may contribute to loss of muscle length, as well as difficulties with postural management [41]. Useful interventions to manage spasticity may include oral medication, focal botulinum toxin injections or intrathecal baclofen [49].

Reduce symptoms

Individuals with different neurological conditions commonly report high levels of problematic symptoms such as pain and fatigue as well as sleep and mood disturbance [50–52]. These symptoms are commonly overlooked and undertreated [53, 54]. Physiotherapy options for these symptoms may include education regarding self-management as well as the use of exercise and acupuncture.

Pain

Pain is commonly a target for physiotherapeutic intervention. Treatment options may include exercise, re-education of movement control, manual or manipulative therapy, education about self-management, graded exposure to problematic activities and pacing of activity level [55]. Pain-relieving modalities used may include transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) or acupuncture [56]. These pain management options may be valuable to people with neurological conditions. There are indications that TENS may be of value for pain associated with spasticity in multiple sclerosis [57]. Neuromuscular stimulation via implanted electrodes may be a useful option to reduce shoulder pain in hemiplegia [58]. A few studies have evaluated the impact of acupuncture on pain in neurological conditions (see Chapter 4).

Fatigue

Fatigue is described as an overwhelming sense of tiredness, lack of energy or exhaustion and is very common in many different neurological conditions [59, 60]. It is a complex symptom with possible contributions from muscle weakness, general physical deconditioning, cognitive impairment, mood disturbance and poor sleep [61, 62]. Active exercise programmes have resulted in reduced fatigue for people with multiple sclerosis [63, 64]. Exercise programmes for other conditions such as stroke have revealed the benefits of increased cardiovascular fitness, but not clear effects on fatigue [65]. Preliminary studies indicate the value of acupuncture for cancer-related fatigue and in fibromyalgia [66, 67]. There are anecdotal reports of improved energy levels and reduced fatigue in neurological conditions following acupuncture but no formal studies.

Sleep disturbance

Sleep disturbance or insomnia includes difficulty falling asleep, staying asleep or non-restorative sleep [68]. In neurological conditions sleep quality is commonly reduced and may be affected by pain, anxiety, muscle spasms in limbs, periodic limb movements or nocturia [69]. Lack of sleep may contribute to daytime fatigue and mood disturbance and commonly coexists with anxiety or depression. Non-pharmacological management includes education regarding good sleep hygiene practices and relaxation. Exercise has long been suggested as an option to enhance sleep quality, but studies evaluating clinical populations are not common [70]. King et al. [71] noted benefits on sleep in older adults following moderate-intensity exercise. Physical exercise using a bicycle ergometer was found to be as effective as dopaminergic agents for sleep disturbed by periodic limb movements in spinal cord injury [72]. Improved sleep quality has been reported by individuals with multiple sclerosis following aerobic and strengthening exercises [73]. Acupuncture may provide reduction of insomnia in a range of psychiatric and medical conditions, although more randomized controlled trials are required [74]. Benefits from acupuncture for sleep quality have been noted in people with Parkinson’s disease and stroke [75, 76].

Mood disturbance

Mood disturbances such as anxiety and depression are highly prevalent in neurological conditions and commonly coexist with pain, fatigue and insomnia. Numerous studies have highlighted the benefits of exercise for depression and anxiety within a wide range of conditions, although large studies of greater rigour are still required [77, 78]. The positive benefits from exercise have also been noted in people with neurological conditions [79]. The evidence for acupuncture in mood disorder is inconclusive, although there have been some positive studies [80]. There are no major studies assessing the impact of acupuncture in neurological conditions, although anecdotal reports and case reports indicate benefit [81]. More research is needed.

Enhance self-efficacy

Self-efficacy in neurological conditions

Many studies have highlighted the impact of low self-efficacy in neurological conditions. In spinal cord injury low self-efficacy was strongly associated with lower self-assessed quality of life [82]. Individuals were also at higher risk of experiencing debilitating pain. In Parkinson’s disease individuals with low balance self-efficacy were able to walk shorter distances than those with higher self-efficacy [83]. In stroke, lower levels of self-efficacy were associated with higher levels of depression, poorer walking ability, poorer function, poorer quality of life, increased disability and greater dissatisfaction with community integration [84–87].

Options to enhance self-efficacy

Self-efficacy may be enhanced by a number of processes. These include helping the individual to experience success when completing a chosen task, the observation of others completing similar tasks, as well as verbal affirmation from others, including health care professionals or peers. These opportunities may be built into standard rehabilitation programmes. Effective goal-setting, based around the individual’s own priorities, with regular review, allows the repeated experience of achievement as successive short-term goals are achieved. Treatment of patients within a group context may provide additional opportunities for the experience of success coupled with peer support. Those with particularly low levels of self-efficacy may benefit from targeted support, especially at times of transition such as discharge from inpatient services [88]. Self-efficacy is an important target for treatment. Treatment programmes focusing on physical ability need to incorporate strategies to enhance self-efficacy to ensure that gains for the individual are maximized.

Provide support

Neurological conditions commonly result in substantial difficulties for the individual. An event such as a stroke, spinal cord injury or traumatic brain injury will change the person’s life forever. A relapse of multiple sclerosis is likely to mean that some functional ability may be lost and not regained. The development of Parkinson’s disease marks the beginning of a process of gradual deterioration of function. Active physiotherapy treatments and education aim to make the best of people’s remaining abilities, but they cannot replace that which is lost. Therefore part of the physiotherapist’s role lies in supporting patients in coming to terms with the ways in which their body, their life and their possibilities for the future have changed [89]. This support provides the background context for all other encounters with the person.

[1] Neurological Alliance. Neuro Numbers: A Brief Review of the Numbers of People in the UK with a Neurological Condition. London: Neurological Alliance, 2003.

[2] Pendlebury S.T. Worldwide under-funding of stroke research. Int J Stroke. 2007;2(2):80-84.

[3] Wade D.T., Halligan P.W. Do biomedical models of illness make for good healthcare systems? BMJ. 2004;329(7479):1398-1401.

[4] Waddell G. Biopsychosocial analysis of low back pain. Baillières Clin Rheumatol. 1992;6(3):523-557.

[5] Engel G.L. The need for a new medical model: a challenge for biomedicine. Science. 1977;196(4286):129-136.

[6] Waddell G. Preventing incapacity in people with musculoskeletal disorders. Br Med Bull. 2006;77–78(1):55-69.

[7] World Health Organization. Towards a common language for functioning, disability and health: ICF. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2002.

[8] Gutenbrunneer C., Ward A.B., Chamberlain M.A. White book on physical and rehabilitation medicine in Europe. J Rehabil Med. 2007;39(S45):1-48.

[9] Department of Health. The National Service Framework for Long-term Conditions. London: Department of Health, 2005.

[10] Martin J., Meltzer H., Eliot D. Report 1: The prevalence of disability among adults. Office of Population, Census and Surveys, Social Survey Division; OPCS surveys of disease in Great Britain, 1988–89, 1988.

[11] RCP. The National Council for Palliative Care, BSRM. Long-term neurological conditions: management at the interface between neurology, rehabilitation and palliative care. London: Royal College of Physicians, 2008.

[12] RCP. National clinical guideline for stroke. London: Royal College of Physicians, 2008.

[13] NICE. Multiple sclerosis: National clinical guidelines for diagnosis and management in primary and secondary care. London: National Institute for Clinical Excellence/National Collaborating Centre for Chronic Conditions, 2003.

[14] Wade D.T. Evidence relating to goal planning in rehabilitation. Clin Rehabil. 1998;12(4):273-275.

[15] Holliday R.C., Ballinger C., Playford E.D. Goal setting in neurological rehabilitation: patients’ perspectives. Disabil Rehabil. 2007;29(5):389-394.

[16] Freeman J.A., Hobart J.C., Playford E.D., et al. Evaluating neurorehabilitation: lessons from routine data collection. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2005;76(5):723-728.

[17] Skinner A., Turner-Stokes L. The use of standardized outcome measures in rehabilitation centres in the UK. Clin Rehabil. 2006;20(7):609-615.

[18] Sackett D.L., Rosenberg W.M., Gray J.A., et al. Evidence based medicine: what it is and what it isn’t. BMJ. 1996;312(7023):71-72.

[19] RCP BRSM. Rehabilitation following acquired brain injury: national clinical guidelines. London: Royal College of Physicians; British Society of Rehabilitation Medicine, 2003.

[20] National Collaborating Centre for Chronic Conditions. Parkinson’s disease; national clinical guideline for diagnosis and management in primary and secondary care. London: Royal College of Physicians, 2006.

[21] World Health Organization. Preventing chronic diseases: a vital investment: WHO global report. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2005.

[22] Holman H., Lorig K. Patient self-management: a key to effectiveness and efficiency in care of chronic disease. Public Health Rep. 2004;119(3):239-243.

[23] Lorig K. Partnerships between expert patients and physicians. Lancet. 2002;359(9309):814-815.

[24] Department of Health. The expert patient: a new approach to chronic disease management for the 21st century. London: Department of Health, 2001.

[25] Marks R., Allegrante J.P., Lorig K. A review and synthesis of research evidence for self-efficacy-enhancing interventions for reducing chronic disability: implications for health education practice (part I). Health Promot Pract. 2005;6(1):37-43.

[26] Dodgson R., Lee K., Drager N. Global health governance: a conceptual review. Geneva: WHO, 2002.

[27] Department of Health. Clinical governance: in the new NHS. London: Department of Health, 1999.

[28] BSRM. Job Centre Plus, RCP. Vocational assessment and rehabilitation after acquired brain injury: inter-agency guidelines. London: Royal College of Physicians, 2004.

[29] Motor Neurone Disease Association. Standards of care to achieve quality of life for people affected by motor neurone disease. Motor Neurone Disease Association, 2000.

[30] CSP. Core standards of physiotherapy practice. London: Chartered Society of Physiotherapy, 2005.

[31] Department of Health, Public Guardianship Office. Mental capacity act 2005 – summary. Department of Health; Public Guardianship Office, 2007. Available online at: http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/SocialCare/Deliveringadultsocialcare/MentalCapacity/MentalCapacityAct2005/DH_064735 10-1-0009

[32] Chartered Society of Physiotherapy. Curriculum framework for qualifying programmes in physiotherapy. London: Chartered Society of Physiotherapy, 2002.

[33] Gordon J. Assumptions underlying physical therapy intervention: theoretical and historical perspectives. Movement science; foundations for physical therapy in rehabilitation. Maryland: Aspen, 2000;1-31.

[34] Shumway-Cook A., Woollacott M. Motor control: translating research into clinical practice. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins, 2007.

[35] Woollacott M.H., Shumway-Cook A. Changes in posture control across the life span – a systems approach. Phys Ther. 1990;70(12):799-807.

[36] Carr J.H., Shepherd R.B. A Motor Relearning Programme for Stroke, 2nd ed. London: Heinemann, 1987.

[37] Carr J., Shepherd R. Stroke Rehabilitation:Guidelines for Exercise and Training to Optimize Motor Skill. Edinburgh: Elsevier, 2003.

[38] Boyer F.C., Percebois-Macadre L., Regrain E., et al. Vestibular rehabilitation therapy. Neurophysiol Clin. 2008;38(6):479-487.

[39] Butler D.S. The sensitive nervous system. Adelaide: Noigroup, 2000.

[40] Carr J., Shepherd R. Movement science; foundations for physical therapy in rehabilitation, 2nd ed. Maryland: Aspen, 2000.

[41] Pope P.M. Severe and complex neurological disability: management of the physical condition. Edinburgh: Elsevier, 2007.

[42] Refshauge K., Ada L., Ellis E. Science-based rehabilitation: theories into practice. Edinburgh: Elsevier, 2005.

[43] Vanswearingen J. Facial rehabilitation: a neuromuscular reeducation, patient-centered approach. Facial Plast Surg. 2008;24(2):250-259.

[44] Schmidt R.A., Wrisberg C.A. Motor Learning and Performance: A Situation-Based Learning Approach, 4th ed. Illinois: Human Kinetics, 2008.

[45] Wolf S.L., Winstein C.J., Miller J.P., et al. Retention of upper limb function in stroke survivors who have received constraint-induced movement therapy: the EXCITE randomised trial. Lancet Neurol. 2008;7(1):33-40.

[46] Ada L., O’Dwyer N., O’Neill E. Relation between spasticity, weakness and contracture of the elbow flexors and upper limb activity after stroke: an observational study. Disabil Rehabil. 2006;28(13/14):891-897.

[47] Holmes K.J., Michael S.M., Thorpe S.L., et al. Management of scoliosis with special seating for the non-ambulant spastic cerebral palsy population – a biomechanical study. Clin Biomech. 2003;18(6):480-487.

[48] Singer B.J., Jegasothy G.M., Singer K.P., et al. Evaluation of serial casting to correct equinovarus deformity of the ankle after acquired brain injury in adults. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2003;84(4):483-491.

[49] Barnes M.P., Johnson G.R. Upper motor neurone syndrome and spasticity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008.

[50] Simuni T., Sethi K. Nonmotor manifestations of Parkinson’s disease. Ann Neurol. 2009;64(S2):S65-S80.

[51] Brown R.F., Valpiani E.M., Tennant C.C., et al. Longitudinal assessment of anxiety, depression, and fatigue in people with multiple sclerosis. Psychol Psychother. 2009;82:41-56.

[52] Leppavuori A., Pohjasvaara T., Vataja R., et al. Insomnia in ischemic stroke patients. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2002;14(2):90-97.

[53] Ludwig J. Parkinson disease: do we need to improve treatment strategies that focus on nonmotor complications such as pain? Nat Clin Pract Neurol. 2008;4(9):478-479.

[54] Korostil M., Feinstein A. Anxiety disorders and their clinical correlates in multiple sclerosis patients. Mult Scler. 2007;13(1):67-72.

[55] Gifford L., Thacker M., Jones M.A. Physiotherapy and pain. In: McMahon S.B., Koltzenburg M., editors. Wall and Melzack’s textbook of pain. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2006:603-617.

[56] Barlas P., Lundeberg T. Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation and acupuncture. In: McMahon S.B., Koltzenburg M., editors. Wall and Melzack’s textbook of pain. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2006:583-590.

[57] Miller L., Mattison P., Paul L., et al. The effects of transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) on spasticity in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2007;13(4):527-533.

[58] Chae J., Yu D.T., Walker M.E., et al. Intramuscular electrical stimulation for hemiplegic shoulder pain: a 12-month follow-up of a multiple-center, randomized clinical trial. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2005;84(11):832-842.

[59] Schepers V.P., Visser-Meily A.M., Ketelaar M., et al. Poststroke fatigue: course and its relation to personal and stroke-related factors. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2006;87(2):184-188.

[60] Belmont A., Agar N., Hugeron C., et al. Fatigue and traumatic brain injury. Ann Readapt Med Phys. 2006;49(6):283-284.

[61] Leocani L., Colombo B., Comi G. Physiopathology of fatigue in multiple sclerosis. Neurol Sci. 2008;29(0):241-243.

[62] Barat M., Dehail P., de Seze M. Fatigue after spinal cord injury. Ann Readapt Med Phys. 2006;49(6):277-279.

[63] Fragoso Y.D., Santana D.L., Pinto R.C. The positive effects of a physical activity program for multiple sclerosis patients with fatigue. NeuroRehabilitation. 2008;23(2):153-157.

[64] Dodd K.J., Taylor N.F., Denisenko S., et al. A qualitative analysis of a progressive resistance exercise programme for people with multiple sclerosis. Disabil Rehabil. 2006;28(18):1127-1134.

[65] Macko R.F., Ivey F.M., Forrester L.W., et al. Treadmill exercise rehabilitation improves ambulatory function and cardiovascular fitness in patients with chronic stroke: a randomized, controlled trial. Stroke. 2005;36(10):2206-2211.

[66] Martin D.P., Sletten C.D., Williams B.A., et al. Improvement in fibromyalgia symptoms with acupuncture: results of a randomized controlled trial. Mayo Clin Proc. 2006;81(6):749-757.

[67] Molassiotis A., Sylt P., Diggins H. The management of cancer-related fatigue after chemotherapy with acupuncture and acupressure: A randomised controlled trial. Complement Ther Med. 2007;15(4):228-237.

[68] Roth T. Insomnia: definition, prevalence, etiology, and consequences. J Clin Sleep Med. 2007;3(5 Suppl):S7-110.

[69] Stanton B.R., Barnes F., Silber E. Sleep and fatigue in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2006;12(4):481-486.

[70] Driver H.S., Taylor S.R. Exercise and sleep. Sleep Med Rev. 2000;4(4):387-402.

[71] King A.C., Pruitt L.A., Woo S., et al. Effects of moderate-intensity exercise on polysomnographic and subjective sleep quality in older adults with mild to moderate sleep complaints. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2008;63(9):997-1004.

[72] de Mello M.T., Esteves A.M., Tufik S. Comparison between dopaminergic agents and physical exercise as treatment for periodic limb movements in patients with spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2004;42(4):218-221.

[73] Smith C., Hale L., Olson K., et al. How does exercise influence fatigue in people with multiple sclerosis? Disabil Rehabil. 2008:1-8.

[74] Kalavapalli R., Singareddy R. Role of acupuncture in the treatment of insomnia: a comprehensive review. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2007;13(3):184-193.

[75] Kim Y.S., Lee S.H., Jung W.S., et al. Intradermal acupuncture on shen-men and nei-kuan acupoints in patients with insomnia after stroke. Am J Chin Med. 2004;32(5):771-778.

[76] Shulman L.M., Wen X., Weiner W.J., et al. Acupuncture therapy for the symptoms of Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2002;17(4):799-802.

[77] Daley A. Exercise and depression: a review of reviews. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2008;15(2):140-147.

[78] Martinsen E.W. Physical activity in the prevention and treatment of anxiety and depression. Nord J Psychiatry. 2008;62(Suppl. 47):25-29.

[79] Macko R.F., Benvenuti F., Stanhope S., et al. Adaptive physical activity improves mobility function and quality of life in chronic hemiparesis. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2008;45(2):323-328.

[80] Karst M., Winterhalter M., Munte S., et al. Auricular acupuncture for dental anxiety: a randomized controlled trial. Anesthesia Analgesia. 2007;104(2):295-300.

[81] Donnellan C.P. Acupuncture for central pain affecting the ribcage following traumatic brain injury and rib fractures – a case report. Acupunct Med. 2006;24(3):129-133.

[82] Middleton J., Tran Y., Craig A. Relationship between quality of life and self-efficacy in persons with spinal cord injuries. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2007;88(12):1643-1648.

[83] Mak M.K.Y., Pang M.Y.C. Balance self-efficacy determines walking capacity in people with Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2008;23(13):1936-1939.

[84] Robinson-Smith G., Johnston M.V., Allen J. Self-care self-efficacy, quality of life, and depression after stroke. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2000;81(4):460-464.

[85] LeBrasseur N.K., Sayers S.P., Ouellette M.M., et al. Muscle impairments and behavioral factors mediate functional limitations and disability following stroke. Phys Ther. 2006;86(10):1342-1350.

[86] Pang M.Y.C., Eng J.J., Miller W.C. Determinants of satisfaction with community reintegration in older adults with chronic stroke: role of balance self-efficacy. Phys Ther. 2007;87(3):282-291.

[87] Bonetti D., Johnston M. Perceived control predicting the recovery of individual-specific walking behaviours following stroke: testing psychological models and constructs. Br J Health Psychol. 2008;13(Pt 3):463-478.

[88] Jones F., Partridge C., Reid F. The Stroke Self-Efficacy Questionnaire: measuring individual confidence in functional performance after stroke. J Clin Nurs. 2008;17(7B):244-252.

[89] Toombs S.K. Healing and incurable illness. In: Fulford K.W.M., Dickenson D.L., Murray T.H., editors. Healthcare ethics and human values: an introductory text with readings and case studies. Massachusetts: Blackwell; 2002:125-132.