Chapter 4 Cultural Issues in Pediatric Care

The Importance of Culture to Medical Practice

Tables 4-1 to 4-3 display some cultural values associated with 4 minority populations in the USA: Latinos, Muslims, Native Americans, and African-Americans, illustrating both areas of significant overlap and great variation that are relevant to health perceptions and health seeking. Latinos may subscribe to the importance of “personalismo,” placing great importance on politeness in the face of stress and adversity and thus expect a display of warmth from their physician, including physical touching such as handshakes, hands on the shoulder, and occasionally hugging. By contrast, in the Muslim culture, for a person to touch the body of a member of the opposite gender, including on the arm or a pat on the shoulder, is considered highly inappropriate.

Table 4-1 CULTURAL VALUES* RELEVANT TO HEALTH AND HEALTH-SEEKING BEHAVIOR

| CULTURAL GROUP | RELEVANT CULTURAL NORMS | |

|---|---|---|

| Description of Norm | Consequences of Failure to Appreciate | |

| Latino | Fatalismo: Fate is predetermined, reducing belief in the importance of screening and prevention | Less preventive screening |

| Simpatia: Politeness/kindness in the face of adversity—expectation that the physician should be polite and pleasant, not detached | Nonadherence to therapy, failure to make follow-up visits | |

| Personalismo: Expectation of developing a warm, personal relationship with the clinician, including introductory touching | Refusal to divulge important parts of medical history, dissatisfaction with treatment | |

| Respecto: Deferential behavior on the basis of age, social stature, and economic position, including reluctance to ask questions | Mistaking a deferential nod of the head/not asking questions for understanding; anger at not receiving due signs of respect | |

| Familismo: Needs of the extended family outrank those of the individual, and thus family may need to be consulted in medical decision-making | Unnecessary conflict, inability to reach a decision | |

| Muslim | Fasting during the holy month of Ramadan: Fasting from sunrise to sundown, beginning during the teen years. Women are exempted during pregnancy, lactation, and menstruation and exemptions for illness, but may be associated with a sense of personal failure. | Inappropriate therapy; will not take medicines during daytime misinterpreted as noncompliance; misdiagnosed |

| Modesty: Women’s body including hair, body, arms, and legs not to be seen by men other than in immediate family. Female chaperone and/or husband must be present during exam and only that part of the body being examined should be uncovered. | Deep personal outrage, seeking alternative care | |

| Touch: Forbidden to touch members of the opposite sex other than close family. Even a handshake may be inappropriate. | Patient discomfort, seeking care elsewhere | |

| After death, body belongs to God: Postmortem exam will not be permitted unless required by law, family may wish to perform after-death care | Unnecessary intensification of grief and loss | |

| Cleanliness essential before prayer: Individual must perform ritual ablutions before prayer, especially elimination of urine and stool. Nurse may need to assist in cleaning if patient is incapable. | Affront to religious beliefs | |

| God’s will: God causes all to happen for a reason, and only God can bring about healing | Allopathic medicine will be rejected if it conflicts with religious beliefs, family may not seek health care | |

| Patriarchal, extended family: Older male typically is head of household, and family may defer to him for decision-making | Child’s mother or even both parents may not be able to make decisions about child’s care; emergency decisions may require additional time | |

| Halal (permitted) vs harem (forbidden) foods and medications: Foods and medicine containing alcohol (some cough and cold syrups) or pork (some gelatin-coated pills) are not permitted | Refusal of medication, religious effrontery | |

| Native American | Nature provides the spiritual, emotional, physical, social, and biologic means for human life; by caring for the earth, Native Americans will be provided for. Harmonious living is important. | Spiritual living is required of Native Americans; if treatments do not reflect this view, they are likely not to be followed |

| Passive forbearance or right of the individual to choose his or her path: Another family member cannot intervene | Mother’s failure to intervene in a child’s behavior and/or use of noncoercive disciplinary techniques may be mistaken for neglect | |

| Natural unfolding of the individual: Parents further the development of their children by limiting direct interventions and viewing their natural unfolding | Many pediatric preventive practices will run counter to this philosophy | |

| Talking circle format to decision-making: Interactive learning format including diverse tribal members | Lecturing, excluding the views of elders is likely to result in advice that will be disregarded | |

| African-American | Great heterogeneity in beliefs and culture among African-Americans | Risk of stereotyping and/or making assumptions that do not apply to a specific patient or family |

| Extended family and variations in family size and child care arrangements are common; matriarchal decision-making regarding health care | Advice/instructions given only to the parent and not to others involved in health decision-making may not be effective | |

| Parenting style often involves stricter adherence to rules than seen in some other cultures | Advice regarding discipline may be disregarded if it is inconsistent with perceived norms; other parenting styles may not be effective | |

| History-based widespread mistrust of medical profession and strong orientation toward culturally specific alternative/complementary medicine | In patient noncompliance, physicians will be consulted as a last resort | |

| Greater orientation toward others; the role of an individual is emphasized as it relates to others within a social network | Compliance may be difficult if the needs of 1 individual are stressed above the needs of the group | |

| Spirituality/religiosity important; church attendance central in most African-American families | Loss of opportunity to work with the church as an ally in health care | |

| East and Southeast Asian | Long history of eastern medicines (e.g., Chinese medicine) as well as more localized medical traditions | May engage with multiple health systems (Western biomedical and traditional) for treatment of symptoms and diseases |

| Extended families and care networks. Grandparents may provide day-to-day care for children while parents work outside of the home. | Parents may not be the only individuals a physician needs to communicate with in regard to symptoms, follow-through on treatments, and preventive behaviors | |

| Sexually conservative. Strong taboos for premarital sexual relationships, especially for women. | Adolescents may be reluctant to talk about issues of sexuality, pregnancy, birth control with physicians. Recent immigrants or native populations may have less knowledge regarding pregnancy prevention, STIs, and HIV. | |

| Infant/child feeding practices may overemphasize infant’s or child’s need to eat a certain amount of food to stay “healthy” | Guidelines for child nutrition and feeding practices may not be followed out of concern for child’s well-being | |

| Saving face. This is a complex value whereby an individual may lose prestige or respect by a third party when a second individual says negative or contradictory statements. | Avoid statements that are potentially value-laden or imply a criticism of an individual. Utilize statements such as “We have now found that it is better to…” rather than criticizing a practice. | |

* Adherence to these or other beliefs will vary among members of a cultural group based on nation of origin, specific religious sect, degree of acculturation, age of patient, etc.

Table 4-2 EXAMPLES OF DISEASE BELIEFS OR PRACTICES

| CULTURAL GROUP | EXAMPLES |

|---|---|

| Latino | Use of traditional medicines (nopales or cooked prickly pear cactus as a hypoglycemic agent) along with allopathic medicine |

| Recognition of disorders not recognized in Western allopathic medicine (empacho, in which food adheres to the intestines or stomach), which are treated with folk remedies but also brought to the pediatrician | |

| Cultural interpretation of disease (caida de mollera or fallen fontanel) as a cultural interpretation of severe dehydration in infants | |

| Muslim | Female genital mutilation: Practiced in some Muslim countries, the majority do not practice it and it is not a direct teaching of the Koran |

| Koranic faith healers: Utilize verses from the Koran, holy water, and specific foods to bring about recovery | |

| Native American | Traditional “interpreters” or “healers” interpret signs and answers to prayers. Their advice may be sought in addition or instead of allopathic medicine. |

| Dreams are believed to provide guidance; messages in the dream will be followed | |

| East and Southeast Asian | Concepts of “hot” and “cold,” whereby a combination of hot and cold foods and other substances (e.g., coffee, alcohol) combine to cause illness. One important aspect is that Western medicines are considered hot by Vietnamese, and therefore, nonadherence may occur if it is perceived that too much of a medicine will make their child’s body hot. Note: Hot and cold do not refer to temperatures, but are a typology of different foods; for example, fish is hot and ginger is cold. Foods, teas, and herbs are also important forms of medicine because they provide balance between hot and cold. |

Cultural Competence

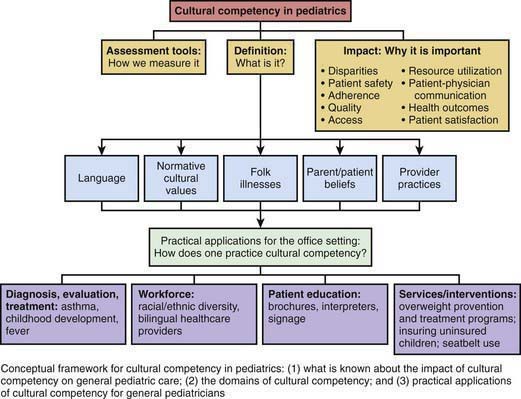

Physicians and patients bring to their interaction personal and professional values from multiple cultural systems that have significant implications for the delivery of health care. Physician “cultural competence” is therefore critical to a successful patient-provider interaction (Fig. 4-1). Campinha-Bacote’s model for understanding and assessing culturally competency is frequently used in education and research: (1) learning to value and understand other cultures, in part through self-awareness of one’s own cultural values (“cultural awareness”); (2) learning basic fundamentals about other cultures, particularly those of the patients with whom the physician will interact (“cultural knowledge”); (3) developing the ability to apply cultural knowledge in patient encounters (“cultural skills”); (4) seeking exposure to cross-cultural interactions (“cultural encounters”); and (5) being motivated to achieve all of the previous (“cultural desire”). This framework provides an important guide to pediatric education and practice and, thus, will serve as the outline for the remainder of this chapter.

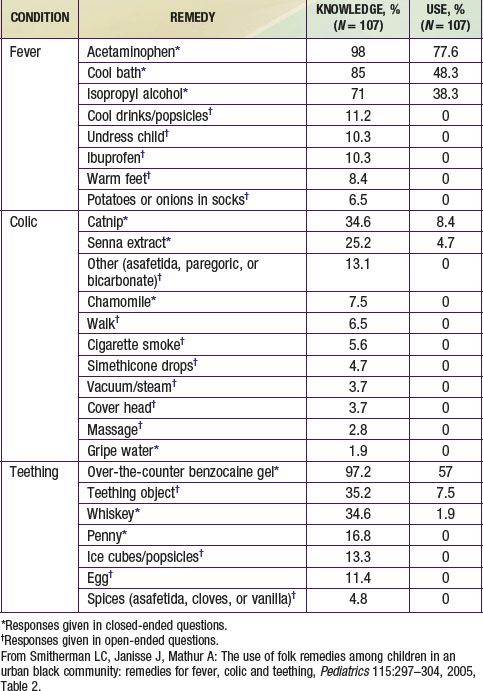

Figure 4-1 Components of cultural competency in pediatric practice.

(From Brotanek JM, Seeley CE, Flores G: The importance of cultural competency in general pediatrics, Curr Opin Pediatr 20:711–718, 2008, Fig 1, p 712.)

Brotanek JM, Seeley CE, Flores G. The importance of cultural competency in general pediatrics. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2008;20(6):711-718.

Bruss MB, Applegate B, Quitugua J, et al. Ethnicity and diet of children: development of culturally sensitive measures. Health Educ Behav. 2007;34:735-749.

Cheah CSL, Chirkov V. Parents’ personal and cultural beliefs regarding young children. J Cross Cult Psychol. 2008;39(4):402-423.

Daley TC. The need for cross-cultural research on the pervasive developmental disorders. Transcult Psychiatry. 2002;39:531-552.

Dumont-Mathieu TM, Bernstein BA, Dworkin PH, et al. Role of pediatric health care professionals in the provision of parenting advice: a qualitative study with mothers from 4 minority ethnocultural groups. Pediatrics. 2006;118:e839.

Flores G. Culture, ethnicity, and linguistic issues in pediatric care: urgent priorities and unanswered questions. Ambul Pediatr. 2004;4:276-282.

Kaljee LM, Green M, Riel R, et al. Sexual stigma, sexual behaviors, and abstinence among Vietnamese adolescents: implications for risk and protective behaviors for HIV, STIs, and unwanted pregnancy. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2007;18(2):48-59.

Kirk-Smith MD, Stretch DD. The influence of medical professionalism on scientific practice. J Eval Clin Pract. 2003;9:417-422.

Lawrence P, Rozmus C. Culturally sensitive care of the Muslim patient. J Transcult Nurs. 2001;12:228-233.

Lieu TA, Finkelstein JA, Lozano P, et al. Cultural competence policies and other predictors of asthma care quality for Medicaid-insured children. Pediatrics. 2004;114:e102-e110.

Reimann JO, Talavera GA, Salmon M, et al. Cultural competence among physicians treating Mexican Americans who have diabetes: a structural model. Soc Sci Med. 2004;59:2195-2205.

Rivero-Vergne A, Berrios R, Romero I. Cultural aspects of the Puerto Rican cancer experience: the mother as the main protagonist. Qual Health Res. 2008;18(6):811-820.

Schousboe I. Local and global perspectives on the everyday lives of children. Culture Psychology. 2005;11:207-227.

Smitherman LC, Janisse J, Mathur A. The use of folk remedies among children in an urban black community: remedies for fever, colic and teething. Pediatrics. 2005;115:297-304.

Stanton B, Galbraith J, Kaljee L, editors. The uncharted path from clinic-based to community-based research. New York: Nova Publishers, 2008.

Stanton B, Huang CC, Armstrong RW, et al. Global health training for pediatric residents. Pediatr Ann. 2008;37:786-798.

Taylor JS. Confronting “culture” in medicine’s “culture of no culture,”. Acad Med. 2003;78:555-559.

Van Esterik P. Contemporary trends in infant feeding research. Annu Rev Anthropol. 2002;31:257-278.

Yoshioka MR, Schustack A. Disclosure of HIV status: cultural issues of Asian patients. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2001;15(2):77-82.