15 Cryosurgery

Cryosurgery is the most commonly performed dermatologic procedure in the United States. There are many different ways to achieve cold temperatures, but clinically, the end result is to freeze the fluid in cells, which causes crystals that damage the cells, resulting in tissue destruction. Different cell types are destroyed at different temperatures (see Table 15-1). Melanocytes are relatively fragile causing the tendency for hypopigmentation with their death. Cartilage and bone are most resistant to freezing and other cells are in between.

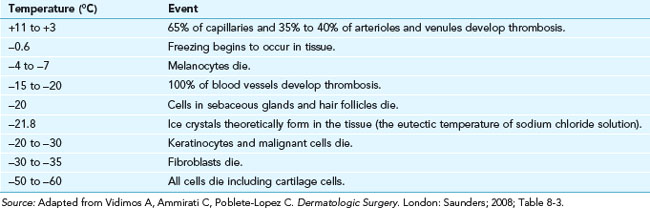

TABLE 15-1 Key Events during Freezing Including Cell Death

|

Temperature (°C) |

Event |

|---|---|

| +11 to +3 | 65% of capillaries and 35% to 40% of arterioles and venules develop thrombosis. |

| −0.6 | Freezing begins to occur in tissue. |

| −4 to −7 | Melanocytes die. |

| −15 to −20 | 100% of blood vessels develop thrombosis. |

| −20 | Cells in sebaceous glands and hair follicles die. |

| −21.8 | Ice crystals theoretically form in the tissue (the eutectic temperature of sodium chloride solution). |

| −20 to −30 | Keratinocytes and malignant cells die. |

| −30 to −35 | Fibroblasts die. |

| −50 to −60 | All cells die including cartilage cells. |

Source: Adapted from Vidimos A, Ammirati C, Poblete-Lopez C. Dermatologic Surgery. London: Saunders; 2008; Table 8-3.

Indications

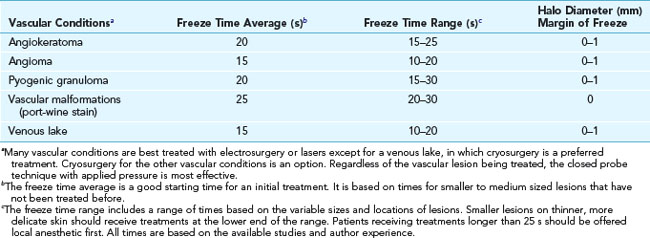

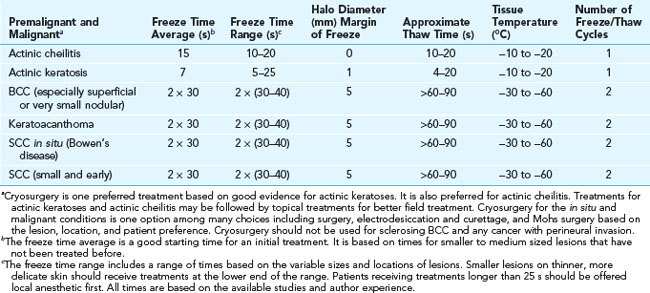

Cryosurgery is most often used to treat actinic keratoses and benign conditions. Table 15-2 provides recommended freeze times and margins of freeze for benign conditions (using liquid nitrogen with an open spray technique). Table 15-3 gives recommended freeze times and margins of freeze for vascular conditions (using liquid nitrogen with a closed probe or an open spray technique). Table 15-4 lists recommendations for treating premalignant and malignant conditions (using liquid nitrogen with an open spray technique). Details on how to perform these procedures follow.

TABLE 15-2 Recommended Freeze Times and Margin of Freeze for Benign Conditions Using Liquid Nitrogen with an Open Spray Technique

Contraindications

|

Contraindications |

Category |

|---|---|

| By Lesion | |

| Melanoma | A |

| Recurrent basal cell carcinoma | A |

| Sclerosing basal cell carcinoma (BCC) | A |

| Micronodular BCC | R |

| Nevus | A |

| Any undiagnosed lesion suspicious for non-melanoma malignancy (tissue should be sent for pathology first) | R |

| Morphea | A |

| By Area | |

| Skin cancer on ala nasi and nasolabial fold | R |

| Neoplasm of upper lip near vermillion border | R |

| Neoplasm over the shins | R |

| By Patient | |

| Previous adverse reaction to cryotherapy (e.g., cold anaphylaxis) | A |

| Cryoglobulinemia | R |

| Myeloma, lymphoma | R |

| Autoimmune disorders (including pyoderma gangrenosum) | R |

| Raynaud’s disease, especially when lesion is on fingers, toes, nose, ears, penis | R |

A, Absolute; R, relative.

Advantages of Cryosurgery

Disadvantages of Cryosurgery

Equipment for Liquid Nitrogen

FIGURE 15-2 Two types of cryosurgical spray guns from Brymill (left) and one from Wallach (right).

(Copyright Richard P. Usatine, MD.)

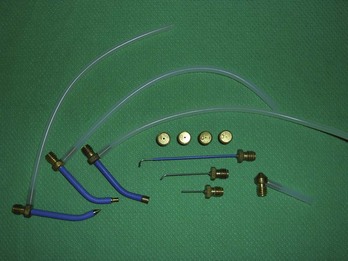

FIGURE 15-4 A large assortment of cryosurgical probes, apertures, and spray tips.

(Copyright Richard P. Usatine, MD.)

Cryosurgery: Principles and Getting Started

|

Factor |

Key Principles |

|---|---|

| Rate of tissue freezing | Rapid freezing causes more cell death. In the open spray technique, this is influenced by the rate of liquid nitrogen spray to the skin (aperture and configuration of the spray conduit). |

| Rate of intermittent spraying |

Source: Adapted from Vidimos A, Ammirati C. Poblete-Lopez C. Dermatologic Surgery. London: Saunders; 2008; Table 8-2.

Cryosurgery Methods

Many different techniques are used to perform cryosurgery. The most common ones are listed in Table 15-7, which explains how the cryogen is applied and its temperature.

|

Cryogens |

Form |

Temperatures (°C) |

|---|---|---|

| Liquid nitrogen | Open spray, closed probes and CTA Tissue temperature is less cold if delivered with CTA |

−196 |

| Nitrous oxide in tank | Closed probes on special gun | −89 |

| Solidified CO2 in tank | Closed probes on special gun | −79 |

| CryoPen | Refrigerated closed probes | −75 |

| Verruca-Freeze (chlorodifluoromethane and propane) | Chemical spray into cones or disposable buds with evaporation producing the cold | −70 |

| Wartner (dimethyl ether and propane) | OTC foam applicator for warts only | −57 |

| Histofreezer (dimethyl ether and propane) | Application is via disposable 2- and 5-mm buds | −55 |

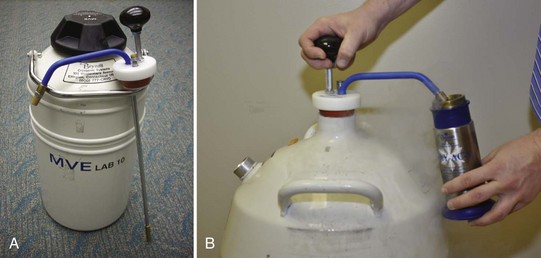

Liquid Nitrogen

Liquid nitrogen is stored in dewar containers ranging in size from 5 to 50 L. The nitrogen may be withdrawn using a ladle, a valve system, or a withdrawal tube (Figure 15-1). The withdrawal tube is the most simple and efficient way to extract liquid nitrogen from your storage container.

A more time-effective and more efficacious approach is to use a cryogun (Figure 15-2). Once filled, the unit can be used to treat many patients rapidly. The spray method allows the clinician to reach tissue temperatures of up to −196°C while the CTA is not likely to get below −20°C. Although there is a cost involved in the purchase of a cryogun, these units can last a clinician’s full career and pay for themselves very quickly. The reimbursement for cryosurgery is excellent for only a few minutes of your time.

Michael D. Bryne developed the first handheld spray device using liquid nitrogen for medical use in 1968. His family continues to run the Brymill Corporation, which sells the most widely used cryoguns. The variety of cryoguns available from Brymill include (Figure 15-2):

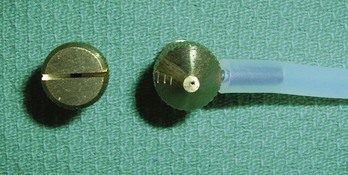

A cryoplate is a transparent plate with four conical openings of various diameters (3, 5, 8, and 10 mm) (Figure 15-8). Used with A – D apertures, the cryoplate provides localization of freezing and protection of sensitive areas such as the eyes. It is good for the novice but is limited by the fact that each opening is round and includes a preset diameter.

FIGURE 15-8 A cryoplate with four different size apertures for controlled freezing diameters.

(Copyright Richard P. Usatine, MD.)

Freezing Times, Thaw Times, and Halo Diameters

The amount of tissue destruction can be estimated by the duration of freezing (freeze time), the amount of thaw time (time until the ice ball is defrosted and is no longer white), and the margin of frozen tissue around the lesion (halo diameter). Factors that affect the freezing of tissue are summarized in Table 15-6.

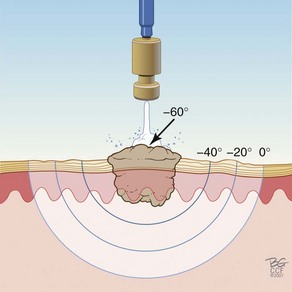

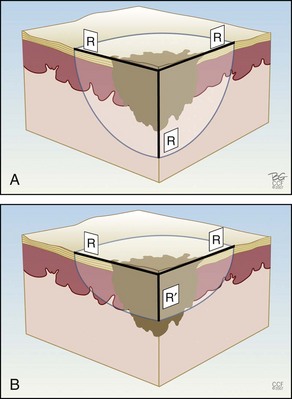

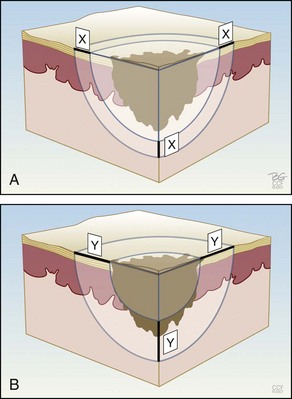

Figure 15-9 shows how the temperature of the freeze is lowest in the middle of a continuous stationary freeze and why a halo diameter is helpful. Figure 15-10 shows the typical geometry of the hemispherical freeze that occurs in the tissues. Figures 15-11 and 15-12 demonstrate the relationship between depth and temperature of freeze to spraying factors. Intermittent spraying close to the skin can increase the depth and temperature of freeze when it is desirable to treat a deep tumor.

Cryosurgery with Liquid Nitrogen Spray: Steps and Principles

Cryosurgery with Liquid Nitrogen Probes: Steps and Principles

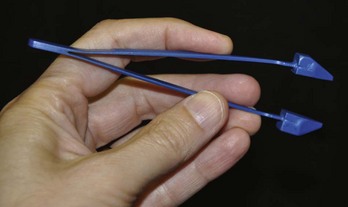

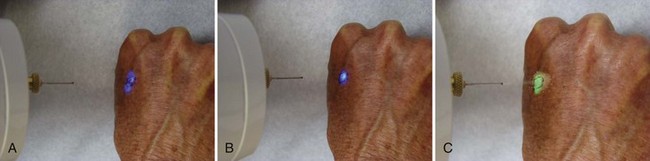

Liquid Nitrogen: Cryo Tweezers

Cryo Tweezers are designed to freeze skin tags without the overspray and inaccuracy inherent in spraying these small raised lesions. The Cryo Tweezers have a Teflon-coated brass tweezer end that holds the cold temperature after dipping them in liquid nitrogen. They have a thin “necked” portion between the heavy tweezer ends and the handle to minimize the cold spread up the handle. The tweezers should be dipped into a Styrofoam cup with LN2 so that the tips are covered, but not the handles. The initial dip should be long enough that the LN2 has stopped boiling away from the originally warm tweezer tips (about 20 seconds). The handles will get very cold, so it helps to wrap them in a 4 × 4 gauze as they are pulled out of the liquid nitrogen. Alternatively, a thick insulated glove can be used to handle the Cryo Tweezers. The skin tags are then grasped and held with the Cryo Tweezers until the freeze margin reaches normal tissue at the skin surface (Figure 15-17). The tweezers can be used to treat many skin tags before they warm up. When treating more than 10 skin tags you may need to redip the tweezers when you note that the freeze time is lengthening.

The Cryo Tweezers are particularly good for skin tags or warts on the eyelids. After grasping the elevated papule, pull the whole lid away from the eye to protect the globe from cryodamage (Figure 15-18). Then continue the freeze until the whole tag or wart is white to the base. This avoids any spray that may enter the eye. Cryo Tweezers can be cleaned between patients by dipping them into the liquid nitrogen again or using an alcohol wipe.

Alternatives to Liquid Nitrogen

Evaporative Liquids

Volatile liquids produce cold temperatures when they evaporate. They are commercially available compressed in various spray cans. These can be directly applied to a lesion by spraying into a cone placed firmly against the patient’s skin to prevent the liquid from running out. After the evaporation, the lesion and a surrounding margin, based on the cone size, will be frozen. These liquids can also be sprayed on or through (depending on the brand) a foam-tipped applicator that comes with the product and then applied to the lesion as with a CTA and liquid nitrogen (see earlier discussion). This technique has a lower initial cost for equipment, but is not as fast and versatile in its use. Also the temperatures are not as cold (see Table 15-6).

Complications

Complications of cryosurgery are listed in Box 15-1. Careful and thoughtful application of the principles in this chapter will prevent most complications.

Treating Specific Lesions

Condyloma

Condyloma acuminata are generally very responsive to cryosurgery. Many lesions can be treated rapidly without local anesthetic. Consider offering topical or local anesthetic to patients who have larger lesions. The bent spray tips are particularly useful for genital and perianal condyloma because the spray volume and speed are somewhat attenuated (Figure 15-20). While this may require slightly longer freeze times, it improves patient comfort during the procedure. The end of the spray tip should be held within 1 to 2 cm of the lesion to get good focused freezing. The patient may be given a prescription for a topical medication such as podofilox or imiquimod to start 2 weeks after cryosurgery. If the patient cannot afford one of these topical medications, cryosurgery may be repeated every 2 weeks until the lesions are gone.

If the perianal lesions are on the anal mucosa or are particularly large, some form of endoscopy should be performed to rule out internal HPV infection in the rectum (Figure 15-21). For perianal lesions in HIV-positive patients, consider a biopsy to rule out squamous cell carcinoma before initiating therapy.

FIGURE 15-21 Condyloma acuminata in the perianal region after liquid nitrogen cryosurgery with a bent tip open spray technique.

(Copyright Richard P. Usatine, MD.)

Make sure you use site-specific billing codes for cryosurgery of the penis, vulva, or perianal area. These do pay at a higher rate (see Table 38-6 in Chapter 38).

Dermatosis Papulosis Nigra

The many small seborrheic keratoses that make up dermatosis papulosis nigra (DPN) can be treated with cryosurgery. Because DPN is more frequently found on the face of women of color, it is important to avoid causing permanent hypopigmentation. This risk should be clearly spelled out and accepted by the patient before starting therapy. This is one time when we suggest getting a written consent signed. It also is prudent to test the cryosurgery out on a few lesions away from the midface to see how the patient will respond before treating many central lesions. The patient in Figure 15-22 was very pleased with her results. She was willing to except some temporary or permanent hypopigmentation just to make sure that her seborrheic keratoses were flattened so they would not show under makeup.

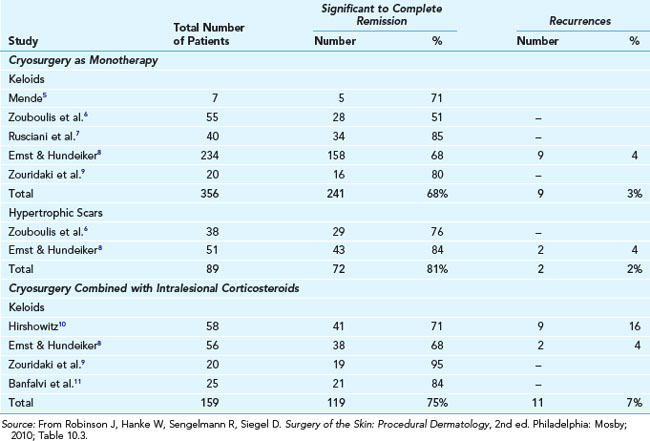

Keloids and Hypertrophic Scars

Keloids and hypertrophic scars can be a frustrating and cosmetically disfiguring complication of injury or irritation to the skin. Treatments have included applying silicone sheeting, excising and injecting the margins with steroids, injection alone, and cryotherapy alone or in conjunction with steroid injection. The data on the use of cryotherapy is nicely summarized in Table 15-8.

Syringomas

Syringomas are benign tumors that occur bilaterally around the eyes, usually on the lower eyelids. They can be treated with cryosurgery using a bent spray method. One simple way to protect the eye is to place a wooden tongue depressor between the syringomas being treated and the closed eye (Figure 15-23).

Vascular Lesions

Hemangiomas

Small or large hemangiomas can be compressed with an adherent cryoprobe and then frozen destroying the vascular tissue. Freeze the cryoprobe first before applying when using liquid nitrogen (Figure 15-24). By freezing the probe first, the probe will not stick to the skin and can be moved to other parts of the hemangioma if the probe is smaller than the hemangioma.

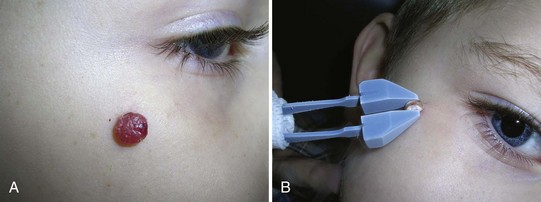

Pyogenic Granuloma

While the success rate for treating a pyogenic granuloma should be higher with a shave excision and electrosurgical destruction, some children will allow you to freeze their lesion but will not permit you to inject local anesthetic for the preferred surgical method. In these cases cryosurgery with a closed probe is preferred over the open spray technique. Because the closed probe can compress the pyogenic granuloma, the freeze can reach the base to decrease the chance of recurrence (Figure 15-25). An alternative is to compress the lesion with a Cryo Tweezer (Figure 15-26).

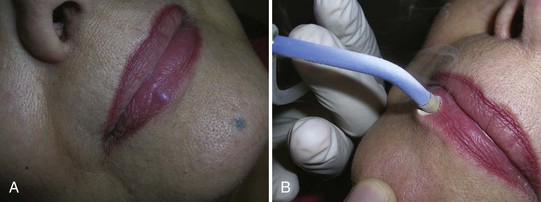

Venous Lakes

Venous lakes are vascular tumors that appear most commonly on the lower lip. They can be compressed with an adherent cryoprobe and then frozen, destroying the venous lake. Freeze the cryoprobe with liquid nitrogen first before applying (Figure 15-27) so that the probe does not stick to the lip when the freeze is complete.

Premalignant Lesions

Actinic Keratoses

Actinic keratoses (AKs) are very amenable to treatment with cryosurgery. Any of the open spray techniques can be used with the cryogun. The smaller lesions can be treated for 5 to 10 seconds, whereas the thicker more hypertrophic lesions should be treated for 10 to 20 seconds. A single freeze cycle should be adequate unless the thaw time appears too short. Table 15-9 shows the percentage cure of actinic keratoses with a single freeze/thaw cycle. Tissue destruction increases if longer freeze times or repeated freeze thaw cycles are performed.3

TABLE 15-9 Actinic Keratoses of the Face and Scalp Larger Than 5 mm—Cure Rates with a Single Freeze3

|

Single Freeze Time (s) |

Cure Rate (%) |

|---|---|

| <5 | 39 |

| 5–20 | 69 |

| >20 | 83 |

The most efficient method of treating many AKs is to have your cryogun with you in the exam room when examining a patient with many AKs. Once you and the patient determine that cryosurgery is to be done, freeze each AK as you find it so that you do not need to find each AK twice (once without and once with the cryogun). Also if you look closely, you will see that the borders of the AK become more visible as the freezing is occurring. Another option is to mark the location of AKs because they are often more easily palpated than seen (Figure 15-28).

Malignant Lesions

After developing proficiency with all kinds of benign lesions, it is reasonable to consider using cryosurgery for the least aggressive nonmelanoma skin cancers. Studies have shown that cryosurgery has similar effectiveness to electrodesiccation and curettage for correctly chosen BCCs. The most commonly recommended regimen is to maintain a freeze for 30 seconds, allow full thawing, and then repeat the 30-second freeze.4 Clinical cure rates are approximately 90%, so appropriate follow-up is important.4 If the lesion recurs after treatment, surgical excision or Mohs surgery may be indicated. These longer freeze times can be painful and difficult to tolerate, so inject with lidocaine for anesthesia prior to treatment. Efficacy and appearance are not as highly rated as surgical management, and after treatment there will likely be a prolonged period (weeks) of erythema, exudate, and healing, so judgment should be used in picking cryotherapy over surgical management.4 It is typical to have some hypopigmentation and skin atrophy after healing.

Use a surgical marker and circle the full skin cancer. If the margins are not clear, do not use cryosurgery for treatment. Measure 5 mm around the border and draw the desired halo diameter (Figure 15-29). Start the freeze and a stopwatch simultaneously—do not just estimate the 30-second freeze time. It helps to have a second person in the room to watch the time on a watch, smart phone, or the Cry-Ac Tracker. In most cases the spray can be held wide open, and intermittent pulsing only needs to be initiated if the freeze ball extends beyond the halo diameter.

Basal Cell Carcinoma

Superficial BCCs and small nodular BCCs can be treated with cryosurgery using liquid nitrogen spray guns because they produce the lowest temperatures in comparison with other cryosurgical techniques. See Contraindications on p.182 for the types of BCCs that should not be treated with cryosurgery.

Squamous Cell Carcinoma

Squamous cell carcinoma in situ responds well to cryosurgery. Small and early squamous cell carcinomas are also candidates for cryosurgery depending on the location and the patient. Decisions made on the choice of therapy for skin cancers involve many factors. See Chapter 34 for a more extensive discussion of these factors. If cryosurgery is chosen as the treatment method, the typical technique involves two 30-second freeze times separated by at least a 1-minute thaw time. As mentioned earlier, most patients will tolerate this best if lidocaine is injected prior to therapy. A keratoacanthoma is one type of well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma and is amenable to cryotherapy using the same treatment technique. The open spray technique with liquid nitrogen is preferred for treating all of these skin cancers.

Learning the Techniques

Bananas, agar plates (Figure 15-10), or uncooked chicken provide good models for practicing cryosurgery. You may observe the pattern of freeze ball that develops based on the aperture used, the rate of flow, and the intermittent spray technique used. If you use a banana or chicken, cut open the frozen area quickly to see the depth and geometry of the freeze. Try rotary or back-and-forth spray motions to cover broader areas for more superficial freezes.

Coding and Billing Pearls

When cryosurgery is used for tissue destruction, coding is based on the skin destruction codes found in Tables 38-5, 38-6, and 38-11 of Chapter 38, Surviving Financially. Benign and premalignant tissue destruction has essentially been divided into three types of CPT codes based on these diagnoses:

The general destruction codes shown in Box 15-2 are usually independent of the method of destruction and the location of the lesions. However, for destructions of benign lesions, certain specific parts of the body are reimbursed at a higher rate including the anus, penis, vulva, vagina, and eyelid. The CPT codes and typical fees charged for these are detailed in Table 38-6 of Chapter 38. Do not forget to use these codes because they do pay better than 17110 and 17111. These specific location codes are not based on the exact number of lesions and a single lesion may be reimbursed the same as many lesions.

Box 15-2 CPT General Destruction Codes

1. Kaufmann R, Spelman L, Weightman W, et al. Multicentre intraindividual randomized trial of topical methyl aminolaevulinate-photodynamic therapy vs. cryotherapy for multiple actinic keratoses on the extremities. Br J Dermatol. 2008;158:994-999.

2. Morton C, Campbell S, Gupta G, et al. Intraindividual, right-left comparison of topical methyl aminolaevulinate-photodynamic therapy and cryotherapy in subjects with actinic keratoses: a multicentre, randomized controlled study. Br J Dermatol. 2006;155:1029-1036.

3. Thai KE, Fergin P, Freeman M, et al. A prospective study of the use of cryosurgery for the treatment of actinic keratoses. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:687-692.

4. Mallon E, Dawber R. Cryosurgery in the treatment of basal cell carcinoma. Assessment of one and two freeze-thaw cycle schedules. Dermatol Surg. 1996;22:854-858.

5. Mende B. [Treatment of keloids by cryotherapy]. Z Hautkr. 1987;62:1348. 1351–1352, 1355

6. Zouboulis CC, Blume U, Buttner P, Orfanos CE. Outcomes of cryosurgery in keloids and hypertrophic scars. A prospective consecutive trial of case series. Arch Dermatol. 1993;129:1146-1151.

7. Rusciani L, Rossi G, Bono R. Use of cryotherapy in the treatment of keloids. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1993;19:529-534.

8. Ernst K, Hundeiker M. [Results of cryosurgery in 394 patients with hypertrophic scars and keloids]. Hautarzt. 1995;46:462-466.

9. Zouboulis CC, Zouridaki E, Rosenberger A, Dalkowski A. Current developments and uses of cryosurgery in the treatment of keloids and hypertrophic scars. Wound Repair Regen. 2002;10:98-102.

10. Hirshowitz B. Treatment of scars and keloids. Br J Plast Surg. 1991;44:318.

11. Banfalvi T, Boer A, Remenar E, Oberna F. [Treatment of keloids (review of the literature, therapeutic suggestions)]. Orv Hetil. 1996;137:1861-1864.