Croup Syndrome

Laryngotracheobronchitis and Acute Epiglottitis

After reading this chapter, you will be able to:

• List the anatomic alterations of the lungs associated with croup syndrome.

• Describe the causes of croup syndrome.

• List the cardiopulmonary clinical manifestations associated with croup syndrome.

• Describe the general management of croup syndrome.

• Describe the clinical strategies and rationales of the SOAPs presented in the case studies.

• Define key terms and complete self-assessment questions at the end of the chapter and on Evolve.

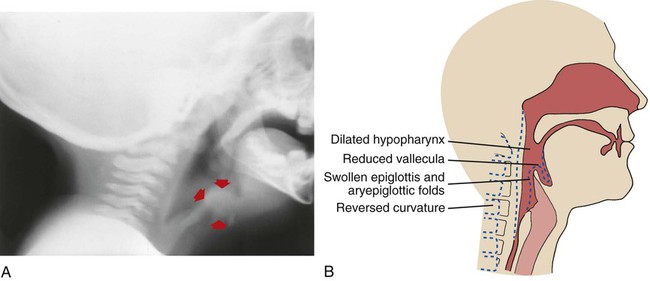

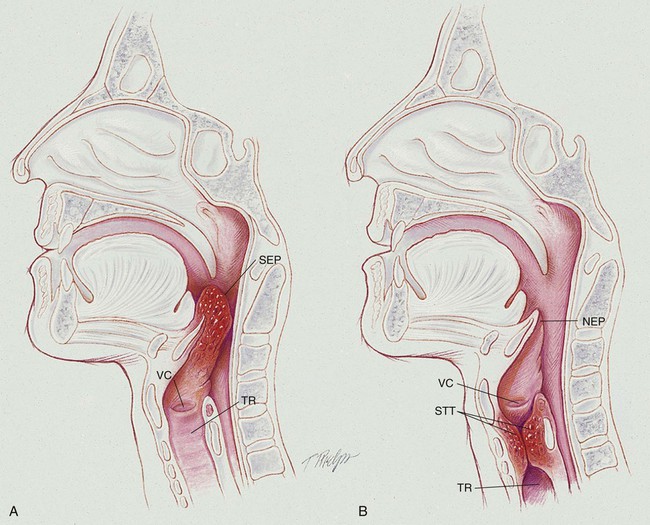

Most experts treat laryngotracheobronchitis (LTB)—which is a subglottic airway obstruction—and the term croup interchangeably, and acute epiglottitis—which is a supraglottic airway obstruction—as two entirely separate disease entities (see Figure 39-1). Historically, this is likely a result, in part, of the fact that the inspiratory stridor (i.e., the croup sound) associated with a patient with LTB is usually a loud and high-pitched brassy sound, whereas the inspiratory stridor associated with a patient with acute epiglottis is often lower in pitch or muffled, or even absent.

Anatomic Alterations of the Upper Airway

Laryngotracheobronchitis

Acute Epiglottitis

Acute epiglottitis is a life-threatening emergency. In contrast to LTB, epiglottitis is an inflammation of the supraglottic region, which includes the epiglottis, aryepiglottic folds, and false vocal cords (see Figure 39-1). Epiglottitis does not involve the pharynx, trachea, or other subglottic structures. As the edema in the epiglottis increases, the lateral borders curl and the tip of the epiglottis protrudes posteriorly and inferiorly. During inspiration the swollen epiglottis is pulled (or sucked) over the laryngeal inlet. In severe cases, this may completely block the laryngeal opening. Clinically, the classic finding is a swollen, cherry-red epiglottis.

The major pathologic or structural changes associated with croup are as follows:

Etiology and Epidemiology

Laryngotracheobronchitis

Acute Epiglottitis*

The general history and physical findings of LTB and epiglottitis are compared and contrasted in Table 39-1.

TABLE 39-1

General History and Physical Findings of Laryngotracheobronchitis (LTB) and Epiglottitis

| LTB | Epiglottitis | |

| Age | 6 months-5 years (with the peak prevalence in the second year) | 2-6 years |

| Onset | Usually slow or gradual (24-48 hours) | Abrupt (2-4 hours) |

| Fever | Absent | Present |

| Drooling | Absent | Present |

| Lateral neck x-ray findings | Haziness in subglottic area | Haziness in supraglottic area |

| Inspiratory stridor | High-pitched, brassy, loud sound | Low-pitched and muffled, or absent |

| Cough | Present (barking or brassy cough) | Absent |

| Hoarseness | Present | Absent |

| Swallowing difficulty | Absent | Present |

| White blood count | Normal (viral—parainfluenza viruses 1, 2, and 3; influenza A and B; respiratory syncytial virus) | Elevated (bacterial—Haemophilus influenza type B) |

General Management of Laryngotracheobronchitis and Epiglottitis

Racemic Epinephrine (MicroNefrin, Vaponefrin)

Aerosolized racemic epinephrine (MicroNefrin, Vaponefrin) usually is administered to children with LTB. This adrenergic agent is used for its mucosal vasoconstriction and is recognized as an effective and safe aerosol decongestant (see Aerosolized Medication Protocol, Protocol 9-4).

CASE STUDY 1

Laryngotracheobronchitis

Admitting History and Physical Examination

Respiratory Assessment and Plan

S Mother reports patient had cough and inspiratory stridor.

O Confirms above. Lungs clear except for stridor and tracheal breath sounds throughout. Vital signs: BP: 90/60, P: 160/minute, RR 50/min. Pallor noted. O2 sat. 92% on room air. CXR and soft tissue x-ray film of neck suggest laryngotracheobronchitis.

A LTB, moderate (history and inspiratory stridor)

P Notify the physician. Start cool mist aerosol treatment and Aerosolized Medication Protocol (med. neb. treatment with racemic epinephrine per protocol). Will obtain throat culture when physician is present.

Discussion

Home remedies sometimes do work. Any parent who has had a child with LTB will find this scenario familiar. What may not be as widely recognized is that sometimes warm and sometimes cool aerosols improve this syndrome. When this approach failed, the parents were wise to bring their son to the emergency department for prompt vasoconstrictive therapy accompanied by a cool mist aerosol. This resulted in prompt improvement. In most pediatric units, decongestant aerosol therapy and mist inhalation are part of the Aerosolized Medication Protocol (see Protocol 9-4). Note the emphasis on family education, including the prn use of racemic epinephrine aerosolization for outpatients. These instructions may have kept the patient from ever returning again to the emergency department to be treated for such an episode.

CASE STUDY 2

Acute Epiglottitis

Admitting History and Physical Examination

Respiratory Assessment and Plan

S Mother states that patient is in severe respiratory distress.

O RR 42/min, BP 80/50, P 140 regular. T 100.6° F. Child’s face puffy, drooling. Inspiratory stridor (worsening). Nail beds cyanotic. On a 4 L/min nasal cannula: Spo2 70%. Soft tissue x-ray exam of neck pending.

• Probable acute epiglottitis. No history of foreign body aspiration (general history).

• Impending acute ventilatory failure (history, drooling, inspiratory stridor, and cyanosis)

P STAT page for anesthesiologist and ENT surgeon. Up-regulate the Oxygen Therapy Protocol and add Aerosolized Medication Protocol pending their arrival (cool mist aerosol with 100% oxygen, with an in-line med-treatment with racemic epinephrine).

*It is of interest to note that George Washington, the first president of the United States, died in the winter of 1799 from acute epiglottitis during an epidemic of influenza. The details of the illness were fully recorded by his secretary, Tobias Lear, and this is the first published description in English of this condition. An account is given of the medical treatment and controversies that arose in criticism of the attendant doctors. (From Cohen B: The death of George Washington 1732-99: the history of “cynanchum,” J Med Biogrid Nov;13(4):225-31, 2005.)

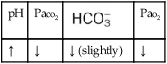

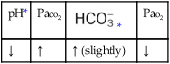

values will be lower than expected for a particular Pa

values will be lower than expected for a particular Pa

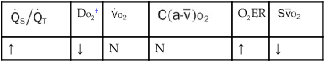

, Arterial-venous oxygen difference; DO2, total oxygen delivery; O2ER, oxygen extraction ratio;

, Arterial-venous oxygen difference; DO2, total oxygen delivery; O2ER, oxygen extraction ratio;  , pulmonary shunt fraction;

, pulmonary shunt fraction;  , mixed venous oxygen saturation;

, mixed venous oxygen saturation;  , oxygen consumption.

, oxygen consumption.