14 Critical care

Severity of illness scoring systems

Initial assessment: ABCDE

Guidelines for initial and daily patient assessment

Initial assessment

• Age, number of days on the unit

Daily investigations

Radiological investigations

Some radiological investigations may require the need for IV and/or oral contrast. Most IV contrast agents are nephrotoxic. The mainstay of prevention is good hydration. An additional bolus of an appropriate crystalloid is often required prior to giving the contrast agent. IV N-acetylcysteine (NAC) is used (p. 686) as a prophylactic agent against contrast-induced nephropathy. Prophylactic pre-procedural haemofiltration appears to be effective in patients with severely diminished renal function.

Discharge from the critical care environment

Dying patients and end-of-life care

Transportation of the critically ill patient

General considerations for patient care in the critical care environment

Infection control

Patient care

Gastrointestinal care

Nutritional support

Early enteral feeding

Prokinetic therapy/enteral feeding failure

Maintenance fluids — IV and enteral

Assessing the adequacy of fluid replacement

Packed red cell transfusion

Glycaemic control

Thrombo-prophylaxis

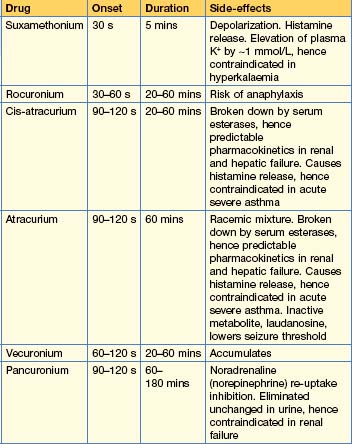

Analgesia and sedation

Guidelines

| Drug | Regime | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Morphine | Loading 5–15 mg Maintenance 1–12 mg/hour |

Slow onset. Long-acting. Active metabolites. Accumulates in renal and hepatic impairment |

| Fentanyl | Loading 25–100 mcg Maintenance 25–250 mcg/hour |

Rapid onset. Modest duration of action. No active metabolites. Renally excreted |

| Alfentanil | Loading 15–50 mcg/kg Maintenance 30–85 mcg/kg/hour (1–6 mg/hour) |

Rapid onset. Relatively short-acting. Accumulates in hepatic failure |

| Remifentanil | Maintenance 6–12 mcg/kg/hour | Rapid onset and offset of action, with minimal if any accumulation of the weakly active metabolite. Significant incidence of problematic bradycardia. Expensive |

| Clonidine | Maintenance 1–4 mcg/kg/hour | An α2 agonist. Has marked sedative and atypical analgesic effects |

| Ketamine | Analgesia Induction 0.2 mg/kg/hour Maintenance 0.5–2.0 mg/kg 1–2 mg/kg/hour |

Atypical analgesic with hypnotic effects at higher doses. Sympathomimetic; associated with emergence phenomena when given at hypnotic doses when usually co-administered with a benzodiazepine. Contraindicated in raised intracranial pressure |

Table 14.1b Continuous infusion sedative regimens

| Drug | Regime | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Propofol 1% | Loading 1.5–2.5 mg/kg Maintenance 0.5–4 mg/kg/hour (0–200 mg/hour) |

IV anaesthetic agent. Causes vasodilatation and hence hypotension. Extrahepatic metabolism, thus does not accumulate in hepatic failure. Has no analgesic properties |

| Midazolam | Loading 30–300 mcg/kg Maintenance 30–200 mcg/kg/hour (0–14 mg/hour) |

Short-acting benzodiazepine. Used with morphine. Active metabolites accumulate in all patients, esp in renal failure |

Respiratory failure

Respiratory support

Continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP)

Non-invasive ventilation

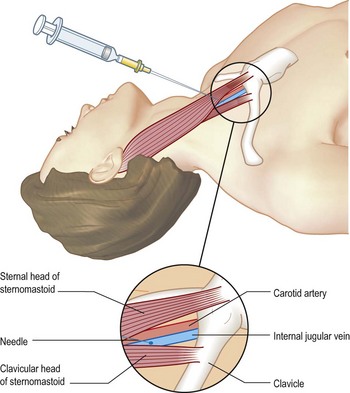

Endotracheal intubation (Box 14.1)

Box 14.1 Endotracheal intubation and tracheostomy

Technique

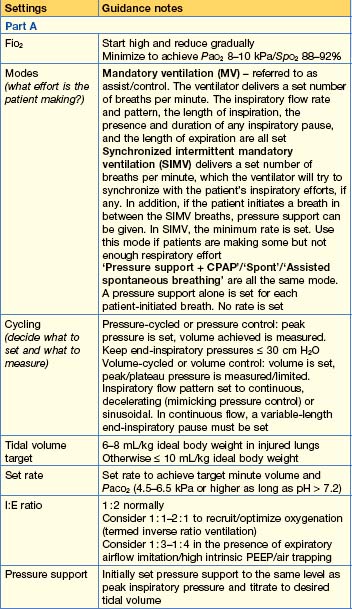

Mechanical ventilation

The mainstay of respiratory support is intermittent positive pressure ventilation (IPPV).

• To fix hypercapnia

• Unconventional ventilation

Complications associated with mechanical ventilation

• Respiratory complications

mismatch and collapse of peripheral alveoli. Traditionally, the latter was prevented by using high tidal volumes (10–12 mL/kg), but high inflation pressures, with over-distension of compliant alveoli, perhaps exacerbated by the repeated opening and closure of distal airways, can disrupt the alveolar–capillary membrane. There is an increase in microvascular permeability and release of inflammatory mediators, leading to VILI. Extreme over-distension of the lungs during mechanical ventilation with high tidal volumes and PEEP can rupture alveoli and cause air to dissect centrally along the perivascular sheaths. This ‘barotrauma’ may be complicated by pneumomediastinum, subcutaneous emphysema, pneumoperitoneum, pneumothorax and intra-abdominal air. The risk of pneumothorax is increased in those with destructive lung disease (e.g. necrotizing pneumonia, emphysema), asthma or fractured ribs.

mismatch and collapse of peripheral alveoli. Traditionally, the latter was prevented by using high tidal volumes (10–12 mL/kg), but high inflation pressures, with over-distension of compliant alveoli, perhaps exacerbated by the repeated opening and closure of distal airways, can disrupt the alveolar–capillary membrane. There is an increase in microvascular permeability and release of inflammatory mediators, leading to VILI. Extreme over-distension of the lungs during mechanical ventilation with high tidal volumes and PEEP can rupture alveoli and cause air to dissect centrally along the perivascular sheaths. This ‘barotrauma’ may be complicated by pneumomediastinum, subcutaneous emphysema, pneumoperitoneum, pneumothorax and intra-abdominal air. The risk of pneumothorax is increased in those with destructive lung disease (e.g. necrotizing pneumonia, emphysema), asthma or fractured ribs.Weaning from IPPV

The weaning process starts the moment IPPV is initiated.

Acute lung injury (ALI) and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS)

Diagnostic criteria

Pathophysiology

Changes include alveolar flooding with proteinaceous fluid (exacerbated by reduced clearance); decreased surfactant production, resulting in atelectasis and decreased compliance; and hyaline membrane formation and interstitial oedema, leading to impaired gaseous diffusion. There is increased intrapulmonary shunt and loss of mechanical defence barrier; hence the high risk of sepsis.

Management

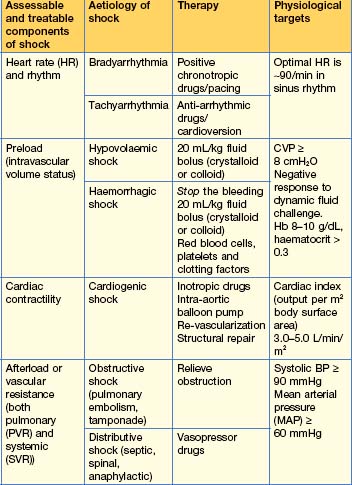

Cardiovascular failure

Terminology and normal values

Methods of continuous haemodynamic monitoring

Invasive arterial and venous pressure monitoring

Pulmonary artery catheterization and thermodilution

This is still the gold standard technique for measurement of haemodynamic status (see below).

Oesophageal Doppler

Cardiovascular supportive therapies

Rate and rhythm control

IV fluid resuscitation, the dynamic fluid challenge or pre-load optimization

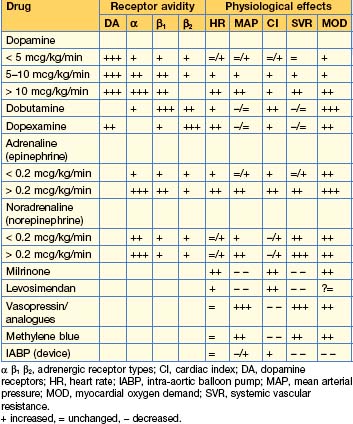

Inotropes, vasopressors and other vasoactive drugs

Table 14.6 Dosage regimens of commonly used vasoactive drugs

| Drug | Dosage range | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Dopamine | 1–20 mcg/kg/min | Dominant effect dependent on dose. Some evidence of worse outcome compared to other drugs, therefore out of favour |

| Dobutamine | 5–20 mcg/kg/min | Inodilator (positive inotropic and causes systemic vasodilatation) |

| Dopexamine | 0.25–2.0 mcg/kg/min | Positive chronotrope/inodilator/anti-inflammatory? |

| Adrenaline (epinephrine) | 0.01–1 mcg/kg/min | Inoconstrictor (positive inotropic causing systemic vasoconstriction) |

| Noradrenaline (norepinephrine) | 0.01–1 mcg/kg/min | Vasoconstrictor (some inotropic activity), first-line vasopressor |

| Milrinone (phosphodiesterase inhibitor) | 150–750 ng/kg/min | Inodilator. Significantly longer onset and elimination half-life than dobutamine. Accumulates in renal failure. Do not give loading dose |

| Levosimendan (Ca sensitizer and K channel opener) | 0.05–0.2 mcg/kg/min | Inodilator. Active metabolite with long elimination half-life, hence 24-hour infusion will have measurable effects for up to 7 days. Do not give loading dose |

| Vasopressin | 0.01–0.05 U/min | Vasoconstrictor. Second-line vasopressor in noradrenaline-resistant shock (see also functional hypoadrenalism) |

| Terlipressin (vasopressin analogue) | 0.25–2 mg bolus | Vasoconstrictor. Duration of action 4–6 hours. Alternative to vasopressin |

| Methylene blue (nitric oxide antagonist) | 2 mg/kg loading 0.25–2 mg/kg/hour |

Vasoconstrictor. 2nd/3rd line vasopressor in norepinephrine resistant shock (see also functional hypoadrenalism) |

Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome (SIRS), Sepsis, Severe Sepsis and Septic Shock

Definitions

Sepsis is defined as SIRS with a documented or suspected infection. Severe sepsis is sepsis with evidence of organ dysfunction (as defined by SOFA or equivalent, p. 31). Septic shock is defined as severe sepsis with hypotension despite adequate fluid resuscitation. Severe sepsis and septic shock are the commonest conditions requiring critical care. Their incidence is high and increasing. They are associated with a very high morbidity and an overall mortality of 30–60%.

The Surviving Sepsis campaign’s recommendations (2004) may be found at www.survivingsepsis.org.

Initial resuscitation: goals during the first 6 hours

Management goals within the first 24 hours (see Emergencies in Medicine, p. 718)

Brain injury

Brainstem death

The process of diagnosing brain death is divided into three parts: pre-conditions, exclusions and tests.

Pre-conditions

Brainstem death tests

Organ and tissue donation

Individual countries have their own processes. In the UK, organ and tissue donation are governed by the Human Tissue Act 2004 (see http://body.orpheusweb.co.uk/HTA2004/20040030.htm). Always consider donation in dying patients, especially in those with brainstem death and, in particular, if the brain injury is the sole organ failure. In the UK, to discuss any aspect of donation, contact your local transplant coordinator.

acute kidney injury

Acute kidney injury (p. 348) is a common complication of critical illness. Kidney injury is associated with increased morbidity and mortality regardless of the primary pathology, with a direct correlation between the severity of renal injury and poor outcome.

Medical management of acute oliguric/anuric renal failure

Renal replacement therapy (p. 357)

Adhikari NKJ, Fowler RA, Bhagwanjee S, Rubenfeld GD. Critical care and the global burden of critical illness in adults. Lancet. 2010;376:1339-1346.

Randall CurtisJ, Vincent J-L. Ethics and end-of-life care for adults in the intensive care unit. Lancet. 2010;376:1347-1353.

Vincent J-L, Singer M. Critical care: advances and future perspectives. Lancet. 2010;376:1354-1361.