Critical Care Patients with Special Needs

SUSAN GALLAGHER, RN, MSN, CNS, PHD

Geriatric Patients:, GINETTE A. PEPPER, PhD, RN, FAAN High-Risk Obstetric Patients:, AMY A. NICHOLS, RN, CNS, EDDPatient Transport:, RENEE HOLLERAN, RN, PhD, CEN, CCRN, CFRN, FAENPediatric Patients:, NANCY BLAKE, RN, MN, CCRN, CNAASedation In Critically Ill Patients: and JAN ODOM-FORREN, MS, RN, CPAN, FAAN

INTRODUCTION

1. Description: Obesity is a multifaceted condition of excess stores of body fat

2. Etiology: Complex and multifactorial

a. Causes may include behavioral, genetic, metabolic, biochemical, cultural, and psychosocial factors

b. Diet, appetite control, ethnicity, and sedentary lifestyle are contributing factors

3. Definitions (American Society of Bariatric Surgery)

a. Body mass index (BMI): Ratio of weight (in kilograms) to the square of height (in meters)

i. Most common and widely accepted means of measuring and expressing the degree of excess weight or obesity

ii. Significantly correlated with total body fat content; caution needed when interpreting BMI in children and in adults with edema, ascites, pregnancy, or highly developed muscles because elevated BMI does not accurately reflect excess adiposity in such cases

iii. Normal: BMI of 18.5 to 24.9

b. Overweight: Excess body weight compared to established standards (e.g., National Center for Health Statistics defines overweight as a BMI of ≥ 27.8 in men and ≥ 27.3 in women). Excess weight may come from muscle, bone, fat, and/or water.

c. Obesity: BMI of 30 or higher

i. Refers to an abnormal proportion of body fat

ii. Individual may be overweight without being obese (e.g., body builder); however, many people are both

e. Bariatrics (from the Greek baros for “weight”): Health care related to the treatment of obesity and associated conditions

a. Recent estimates suggest that more than 67% of U.S. adults are overweight (Goulenok, Monchi, and Chiche, 2004)

b. Among Americans aged 26 to 75 years, 10% to 25% are obese and more than 3% to 10% are morbidly obese, which reflects an increase of more than 25% over the past three decades irrespective of age, gender, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, or race

c. Worldwide problem in both developed and developing countries

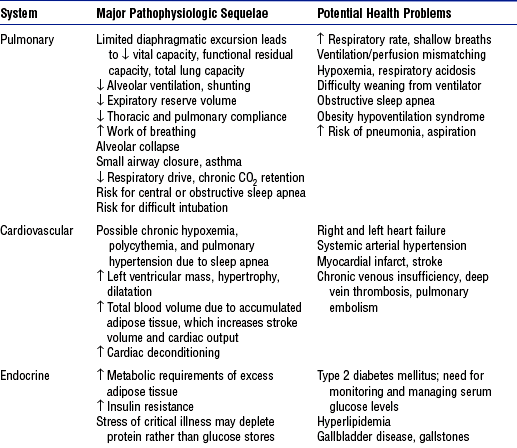

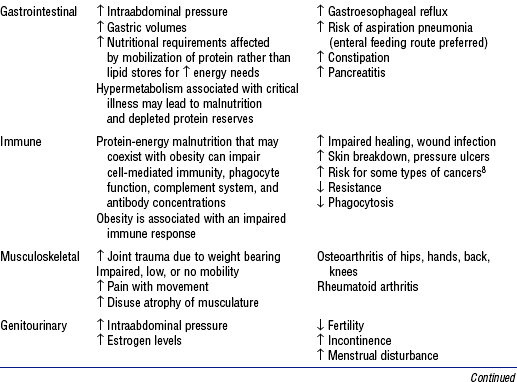

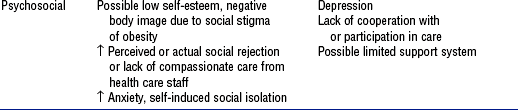

5. Pathophysiology of obesity: Physiologic sequelae of excess body weight adversely affect most body systems (Table 11-1)

6. Clinical significance to critical care nursing

a. Recent evidence suggests that high BMI may be an independent prognostic risk factor for mortality in intensive care unit (ICU) patients

b. Obesity is directly and indirectly associated with a wide spectrum of serious health disorders (see Table 11-1) that may accompany, underlie, and complicate whatever caused the patient to be admitted into a critical care unit

c. When obese patients are hospitalized, they pose a number of additional challenges to health care facilities and staff

i. Increased risk for all complications related to the immobility imposed by their size (i.e., skin breakdown, cardiac deconditioning, atelectasis, deep venous thrombosis, muscle atrophy, urinary stasis, constipation, bone demineralization)

ii. Likelihood of longer length of stay than nonobese

iii. Vulnerability to care issues more or less unique to this population

(a) Technical difficulties with common procedures such as endotracheal intubation, weaning from mechanical ventilation, positioning, weighing, and ambulation

(b) Challenges in establishing vascular access, managing fluid balance, and determining nutritional requirements

(c) Altered pharmacokinetics for some drugs due to differences in metabolism, protein binding, distribution, and clearance in obese persons, which leads to uncertain effects

(d) Inability to use some diagnostic tests due to size or weight limits

(e) Lack of availability of equipment, supplies, or additional staff that optimal care might suggest

NURSING CARE OF THE CRITICALLY ILL BARIATRIC PATIENT

a. Obesity hypoventilation syndrome (also known as Pickwickian syndrome)

i. Definition: Oxygenation decreases as BMI increases, likely due to elevated intraabdominal pressure in which mass and weight compress the thoracic cavity and limit diaphragmatic excursion. Chronic CO2 retention leads to hypercapnia, respiratory acidosis, and dependence on hypoxia for ventilatory drive.

ii. Related to obstructive sleep apnea, characterized by drowsiness, narcosis, daytime napping, difficulty sleeping at night, fatigue, hypersomnolence, depression, right heart failure, and further weight gain

iii. Incidence of respiratory complications has a direct relationship to BMI, especially among those over 350 lb

iv. Risk factors include male gender, middle age, mild sedation, BMI over 30

v. Intervention: Noninvasive positive pressure ventilation can be tried; however, mechanical ventilation must be readily available

i. Obese patients are at risk for respiratory failure due to their high oxygen consumption, decreased functional residual capacity (FRC) (which decreases exponentially with increased BMI), decreased expiratory reserve volume, and decreased total lung capacity

ii. FRC may fall into the range of closing capacity, which leads to small airway closure, ventilation/perfusion mismatch, arterial hypoxemia, and limited oxygen reserve

iii. Obese patients often experience diaphragmatic fatigue. Pressure-supported ventilation alone or with backup allows resting of the diaphragm.

(a) Mechanical ventilation initiated with a tidal volume (VT) of 5 to 7 ml/kg, based on ideal (not actual) body weight, then titrated to the patient’s ventilator mechanics

(b) Placement in reverse Trendelenburg’s position at 45 degrees may improve respiratory mechanics, maximize lung function, and increase successful ventilation or weaning. Supine position leads to decreased compliance and increased airway resistance.

(c) Placement in the prone position can improve FRC, compliance, and oxygenation. Placing a morbidly obese patient in the prone position is difficult but not impossible; hydraulic lifts help. Positive caregiver attitude and preplanning are essential.

v. Airway management requires securing of the airway, intubation, secretion control, use of special equipment, and proper positioning

(a) Assess risk factors for airway placement

(6) Protruding or missing maxillary incisors

(8) Unusually small or large mandible

(b) Measure the distance from the sternal notch to the tip of the chin in the neutral and maximally extended positions (extension should increase by 5 cm)

(c) Intubation may be challenging, with difficulty in visualizing landmarks. The Combitube is an esophageal-tracheal double-lumen airway recognized by the American Heart Association and the American Association of Anesthesiologists as an alternative to the endotracheal tube for use in obese patients.

vi. Failure to control tracheostomy secretions leads to skin breakdown, odor, and threat to a patent airway. For patients with a thick, short neck and excessive parapharyngeal fat deposits, tracheostomy surgery can be difficult, because the trachea may be buried deep in tissues. Wound is managed like any other open wound: Nonadhesive, absorbent, ¼-inch foam dressing is used to absorb excess drainage, protect the wound, and prevent injury from adhesives. Tracheostomy ties should be longer and wider to prevent trauma within skin folds.

vii. Equipment should be tailored to best serve patient and caregiver needs

c. Pneumonia (see also Chapter 2)

i. Most common cause of death from hospital-associated infection, with a prevalence of 5 to 10 per 1000 admissions. Incidence is fourfold higher in intubated, mechanically ventilated patients, because of decreased VT, decreased mucociliary transport, increased atelectasis, and infectious complications, which lead to increased morbidity and mortality.

(a) Literature suggests that the widely accepted standard of care calling for repositioning every 2 hours is seldom met; even when it is included in the hospital-mandated protocol, the standard is met only 50% of the time in critical care settings (Krishnagopalan, Johnson, and Low, 2002)

(b) Until pneumonia resolves, wound healing usually plateaus or deteriorates. Use of full-body lateral rotation therapy may reduce interface pressures, promote pulmonary function, and provide therapeutic positioning. Value of rotation therapy when used to prevent physical hazards of immobility and to manage difficulties with repositioning must be determined.

2. Potential skin integrity complications: Pressure ulcers

a. Result from pressure, friction, and/or shear; often related to insufficient frequency of and/or ineffective repositioning of the very obese patient as well as the presence of multiple overlapping skin folds that can foster the growth of bacteria or yeast

b. Contributing factors include moisture, dehydration, and malnutrition

c. Staging depends on the depth of damage to underlying tissue

d. Obese patients are at risk for atypical pressure ulcers caused by pressure within skin folds related to tubes, catheters, or an ill-fitting chair or wheelchair

i. Pressure within skin folds can be sufficient to cause skin breakdown; tubes and catheters burrow into skin folds and further erode the skin surface

ii. Pressure from side rails or armrests not designed to accommodate a larger person can cause pressure ulcers on the patient’s hips

(a) Use equipment properly sized for the patient

(b) Place and secure tubes so the patient does not rest on them

(c) Reposition (including tubes, lines, catheters) at least every 2 hours

(d) In patients with a large abdominal panniculus, it too must be repositioned to prevent ulceration beneath the panniculus. Alert patients can help lift the panniculus; dependent or unconscious patients can be turned onto the side to aid the nurse in lifting it.

e. Rotation therapy can afford effective and timely repositioning for very large patients who otherwise pose a considerable challenge to frequent turning. Even when rotation therapy is used, precautions must be taken to prevent friction and shear by using correct pressure settings, using an appropriately sized surface, and monitoring skin integrity frequently.

3. Other potential complications related to obesity: See Table 11-1

CARE OF THE MORBIDLY OBESE BARIATRIC SURGERY PATIENT

2. Potential postoperative surgical problems (beyond usual surgical risks such as bleeding, infection, emboli, aspiration, etc.), especially for open abdominal (vs. laparoscopic) procedures, for the morbidly obese and for those with underlying cardiopulmonary disorders

RELATED BARIATRIC CARE ISSUES

a. Potential for physical injury

i. Increasing incidence, cost, and number of back injury claims associated with patient care. More than half of strains and sprains are attributed to manual lifting. Manual lifting and transferring of patients are among the most frequent causes of nursing-related injuries.

ii. Lack of appropriate equipment and/or staff support at the facility

b. Greater complexity: Nursing care becomes increasingly more complicated and problematic as the size and weight of the patient population increase

c. Attitudes toward obese patients may include and communicate a negative bias

a. Standard hospital equipment, such as chairs or bed frames, may pose safety risks for obese patients and their caregivers

b. Equipment specially designed for obese patients can improve quality of care, reduce length of stay, and make care easier and safer by reducing work-related back injuries among caregivers and lowering the risk of patient injury

c. Heavy-duty walkers (for patients weighing 300 to 1000 lb) and heavy-duty beds, lifts, and wheelchairs that support up to 1000 lb are available to facilitate mobilization of very large patients. Preplanning with vendors is important.

a. Policy makers, insurance carriers, health care facilities, and clinicians all need to use standardized measurements and definitions when developing policies, procedures, and protocols for critically ill bariatric patients

b. Bariatric patient criteria (e.g., actual weight, width at widest point, or BMI) should determine which health care professionals and resources are needed in patient care to prevent complications and improve outcomes

i. Institutional policies and procedures must be available to obtain transport, transfer, and patient care devices

ii. Criteria-based protocols for the use of bariatric devices are designed to ensure more appropriate, timely, and cost-sensitive use of equipment

iii. Performance improvement teams can help develop and implement policies and identify resources for bariatric equipment needs

c. Health care professionals on the bariatric care team (physical therapist occupational therapist, or respiratory therapist; internist; bariatric surgeon; dietitian; bariatric clinical nurse specialist; wound, ostomy, and continence nurse; pharmacologist; home care coordinator; equipment vendors) need to be interested in improving critical care for the obese patient

AGE-RELATED BIOLOGIC AND BEHAVIORAL DIFFERENCES

1. Biologic and behavioral differences between older adults and younger adults require modification of nursing care

2. Age-related changes derive from three sources, according to Sloane’s rule of thirds (1992):

a. One-third are related to disease processes that are more common in older adults

b. One-third are related to disuse and inactivity, which increase with age

c. One-third result from the aging process and occur in virtually all people who live long enough. These changes aggravate diseases and the changes associated with disuse.

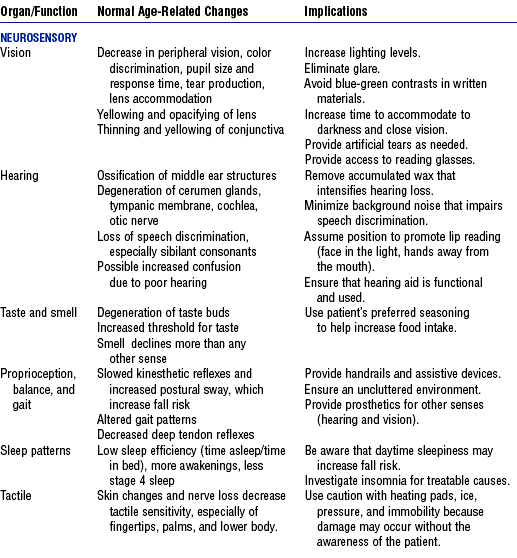

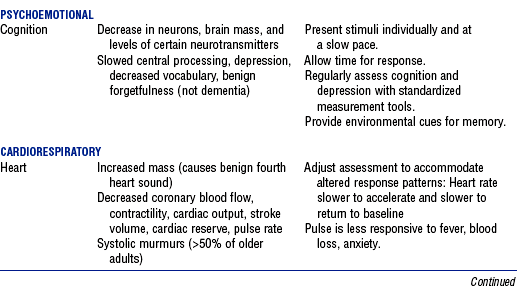

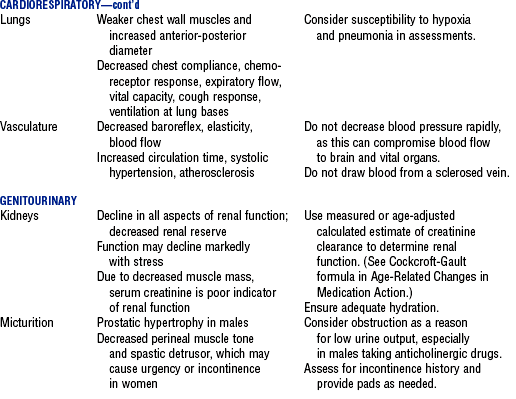

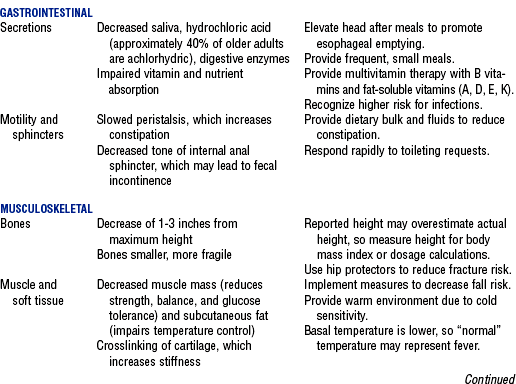

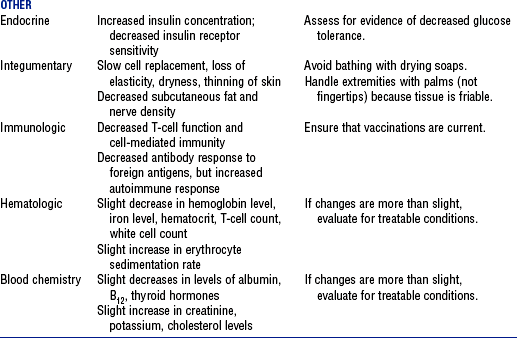

3. Normal age-related changes and implications for nursing care are summarized in Table 11-2

TABLE 11-2

Compiled from Beers MH, Jones TV, Berkwits M, et al: The Merck manual of health and aging, Whitehouse Station, NJ, 2004, Merck Research Laboratories; Ebersole P, Hess P, Luggen AS: Toward healthy aging, ed 6, St Louis, 2004, Mosby; Kane RL, Ouslander JG, Abrass IB: Essentials of clinical geriatrics, ed 5, New York, 2004, McGraw-Hill; and Timeras PS, editor: Physiological basis of aging and geriatrics, ed 3, Boca Raton, Fla, 2003, CRC Press. McGraw-Hill

AGE-RELATED CHANGES IN MEDICATION ACTION

1. Adverse drug reactions are more common in older adults than young adults (Routledge, Mahony, and Woodhouse, 2003)

2. Major reason older adults have more adverse drug reactions is that they have more diseases and take more medications, but age-related changes in drug pharmacokinetics also contribute. The most clinically significant pharmacokinetic changes in old age include the following (Pepper, 2004; Turnheim, 2003):

a. Absorption of drugs shows few age-related changes, although decreased gastric acid alters the dissolution of some drugs (e.g., enteric-coated tablets dissolve faster and may cause irritation)

b. Distribution of drugs is altered by changes in body composition. Greater fat mass increases the storage and half-life of lipid-soluble drugs (e.g., psychotropic drugs). Highly protein-bound drugs (>90% bound) are more likely to be involved in drug interactions.

c. Metabolism of high-clearance drugs (those that are avidly metabolized) is decreased due to decreased liver blood flow

i. If a drug reference indicates that a drug undergoes first-pass metabolism, it has a high hepatic clearance

ii. Effects of agents with high hepatic clearance should be assessed carefully to detect toxicity, especially if an elderly patient is not prescribed a dose lower than the typical adult dose

d. Excretion of drugs that are eliminated unchanged or as active metabolites by the kidneys is markedly impaired with aging

3. Drug interaction is another important factor in adverse drug reactions in older adults, primarily due to the number of drugs taken. The most significant drug interactions include the following:

a. Drugs that decrease gastric acid production (e.g., H2-blockers, proton pump inhibitors, antacids) may alter the absorption of oral drugs

b. Concurrent use of two drugs highly bound (>90%) to plasma albumin will increase the effect of one or both drugs, especially if drug elimination is impaired by age or disease. Use a current drug handbook for data on the degree of protein binding.

c. Drugs that induce or inhibit cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzymes can cause drug toxicity. Use a reference source that is frequently updated, such as Drug-Interactions.com (2005). CYP inhibition is the most significant drug interaction–related cause of adverse drug effects in elderly patients.

d. Drugs whose output is affected by urine pH (quinidine, amphetamines, ephedrine, phenobarbital) or that undergo tubular secretion (probenecid, cimetidine, omeprazole) can interact with and contribute to the toxicity of drugs like methotrexate, procainamide, acyclovir, nitrofurantoin, and cisplatin (Karyekar, Eddington, Briglia, et al, 2004)

4. Nonadherence to the drug regimen and prescribing error, in addition to physiologic and pharmacologic factors, may contribute to adverse drug reactions

a. Nonadherence with the prescribed drug regimen is a common cause of hospitalization among the elderly, although many comply closely with the regimen for prescribed medications (Beijer and de Blaey, 2002)

i. Teaching patients about medications as they are administered in the hospital may improve knowledge and result in better adherence (Barat, Andreason, and Damsgaard, 2001)

ii. At a minimum, the name and purpose of the medication should be stated at the time of administration if the patient is awake and cognitively intact

b. Often there is no accurate list of a patient’s medications during transitions (from home to hospital; from unit to unit in the hospital), which are times of high risk for prescription and transcription error

i. Elderly patients are more likely to have errors in the medication list (Bedell, Jabbour, and Goldberg, 2000)

ii. Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO, 2005) recommends the reconciliation of medication lists at transitions to promote accuracy in medication regimens (Pronost, Weast, and Schwarz, 2003)

c. Expert consensus panels have identified medications to avoid prescribing for older adults; the guidelines regarding potentially inappropriate medication use are called the Beers criteria (Fick et al, 2003)

COMMON GERIATRIC SYNDROMES

1. Geriatric syndromes are broad categories of signs and symptoms that may have a variety of contributing factors, including normal aging changes, multiple diagnoses, and adverse effects of therapeutic interventions. Syndromes are a major focus of nursing research and best practice guidelines.

2. SPICES is a tool for assessing major geriatric syndromes (Wallace and Fulmer, 1998). Pain is another important geriatric syndrome.

3. Nutritional and hydration disorders

a. Older adults with multiple illnesses are at risk for malnutrition (Lawrence and Amella, 2004). Risk factors for decreased muscle mass, poor immune function, and poor outcomes include underweight (BMI <19) and overweight (BMI >26).

b. Mini Nutritional Assessment (MNA) is a quick, noninvasive screening and assessment tool to identify older adults at risk of malnutrition (Nestlé Nutrition, 2005). Seek nutritional team consultation for at-risk elderly.

c. Assess hydration status using a dehydration risk appraisal checklist. If no parenteral fluids are being administered, consider shortening the nothing-by-mouth time before diagnostic tests (2 hours) and replenish fluids as soon as tests are completed (Mentes, 2004).

a. “Geriatric triad” includes three conditions that can cause confusion: Delirium, depression, and dementia

b. Delirium is an acute, reversible, life-threatening syndrome characterized by fluctuating alteration in mental status, inattention, and altered level of consciousness. Stereotypy (repetitive behaviors such as picking at the bedding) may be present. It is a cognitive reaction to a physiologic state.

i. Prevalence is up to 25% of the hospitalized elderly and up to 65% of postoperative elderly patients older than 70 years of age (Beers, 2005). Increases the risk for death or poor outcome.

ii. Mnemonic DELIRIUM summarizes the most common causes:

(c) L: Lack of drugs (withdrawal)

(f) I: Intracranial events (stroke, meningitis)

iii. Confusion Assessment Method is used to differentiate delirium from dementia and other conditions (Inouye, van Dyck, Alessi, et al, 1990)

iv. Having a family member or sitter present until the physical condition is resolved reassures the patient

c. Dementia is a chronic, irreversible, progressive condition with insidious onset that is characterized by memory and thinking deficits involving orientation, visuospatial skills, language, judgment, concentration, and the ability to sequence tasks

i. Present in about one third of the hospitalized elderly but undiagnosed in many. Often dementia is uncovered by the stress of hospitalization (Mezey and Maslow, 2004). Unrecognized dementia increases the risk for delirium (Fick and Foreman, 2000).

ii. Question the family or identify behaviors to detect dementia (Mezey and Maslow, 2004)

d. Depression is common in older adults, affecting up to 43% of older adults in acute care. Can be reversed if detected early. Untreated depression can lead to cognitive impairment, physical debilitation, and suicide (Kurlowicz, 1999).

a. Incidence and severity of falls is higher among hospitalized patients than among the community-dwelling elderly. Injury rate for hospital falls is 10% to 25%. Injuries associated with falls account for 6% of medical expenses for older adults (American Geriatric Society, 2001).

b. Risk for falls is multifactorial. JCAHO 2005 goals require facilities to assess and periodically reassess patients’ risk for fall. Validated risk assessment tools are the Morse Falls Scale (Morse, Morse, and Tylko, 1989) and the Fall Assessment Tool (Farmer, 2000; Hollinger and Patterson, 1992).

c. Implement standardized and individualized fall prevention program (Resnick, 2003)

a. Pain management principles are the same as for other age groups

b. Regular assessment for pain is imperative. Cognitively impaired older adults can give reliable reports of whether they currently have pain. Pain scale most commonly preferred by older adults is a verbal descriptor scale, rather than a visual analogue, face, or numerical scale.

c. Due to age-related changes in pharmacokinetics, older adults do not tolerate some analgesics (Ferrell, 2004; McCaffery and Pasero, 1999):

i. Propoxyphene-containing drugs carry an excess risk of central nervous system (CNS) adverse effects with limited analgesic benefit

ii. Meperidine has a toxic metabolite that accumulates in older adults due to decreased renal function, which results in irritability or even seizures. Avoid repeated dosing if used at all.

iii. Mixed agonist-antagonist analgesics should be avoided in older adults due to their unreliable efficacy and cognitive and cardiovascular effects

iv. Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) such as ibuprofen carry a high risk of gastrointestinal adverse effects with prolonged or regular use. Cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors (e.g., celecoxib) carry a cardiovascular risk.

v. Regular dosages of acetaminophen are preferred for osteoarthritis, but the total dose should not exceed 4 g/day. Some older adults have experienced hepatic damage at 3 g/day, so the minimum effective daily dose should be used.

vi. Long-acting opioids (e.g., methadone) and amitriptyline (Elavil) should be avoided due to potential adverse effects

END-OF-LIFE CARE

1. Advance directives: Legal in every state, but laws vary widely (Warm and Weismann, 2000)

a. There are two types of advance directive:

i. Living will: Written document that specifies a person’s wishes regarding medical care if the person becomes unable to communicate at the end of life

ii. Health care power of attorney, also called the durable power of attorney for health care or health care agent: Appoints someone to make decisions if the patient is unable to communicate. A financial power of attorney is different and does not permit the holder to make health care decisions.

b. Nurses can help patients understand advance directives (Douglas and Brown, 2002)

2. Syndrome of imminent death (Weisman, 2000)

a. Progresses through three stages over 24 hours to 2 weeks

i. Early stage: Either hypoactive or hyperactive delirium or increasing sleepiness, bed bound

ii. Middle stage: Further decline in mental status; pooled oral secretions from loss of swallowing reflex results in “death rattle”; fever is common

iii. Late stage: Coma; altered respiratory pattern—either fast (as high as 40 breaths/min) or slow; cold extremities

b. Confirm treatment goals with the family when the syndrome is recognized. Discuss the removal of treatments that do not contribute to comfort. Scopolamine may be used to dry secretions (decrease death rattle) and morphine may be used to control rapid respirations (goal is 10 to 15 breaths/min). Provide meticulous mouth and skin care.

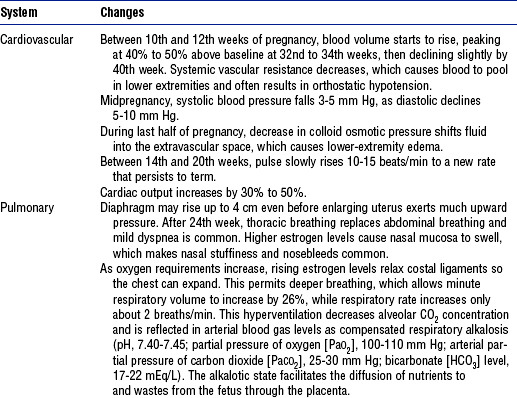

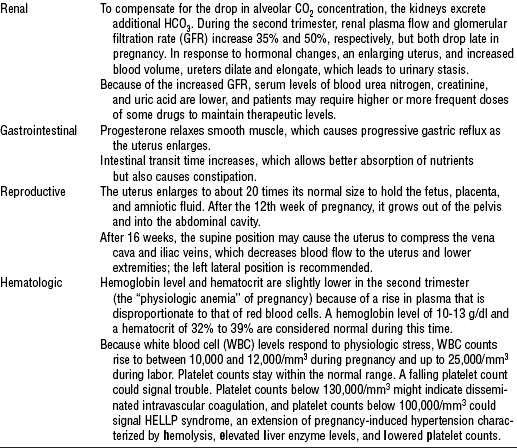

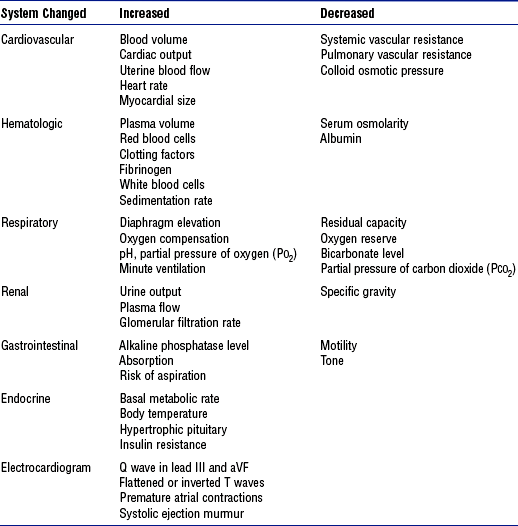

PHYSIOLOGIC CHANGES IN PREGNANCY

During pregnancy, nearly every body system undergoes adaptations that protect the growing fetus and prepare the mother for delivery. Some changes appear early and continue throughout gestation; others occur later. Tables 11-3, 11-4, and 11-5 summarize some of the most significant normal changes that critical care nurses need to keep in mind. Box 11-1 defines some common obstetric abbreviations that may be encountered in obstetric patients’ charts.

TABLE 11-5

Comparison of Hemodynamic Profiles in Pregnant and Nonpregnant Women

| Hemodynamic Parameter | Pregnant | Nonpregnant |

| Cardiac output (L/min) | 6.2 | 4.3 |

| Central venous pressure (mm Hg) | 3.7 | 3.6 |

| Colloid osmotic pressure (mm Hg) | 18 | 20.8 |

| Heart rate (beats/min) | 83 | 71 |

| Left ventricular stroke index (ml/beat) | 48 | 41 |

| Mean arterial pressure (mm Hg) | 90 | 86 |

| Pulmonary capillary wedge pressure (mm Hg) | 7.5 | 6.3 |

| Pulmonary vascular resistance (dyne/sec/cm−5) | 78 | 119 |

| Systemic vascular resistance (dyne/sec/cm−5) | 1210 | 1530 |

POSTPARTUM HEMORRHAGE

1. One of the leading causes of maternal morbidity and mortality, contributing to 30% of obstetric deaths. Definitions include subjective assessments of blood loss greater than standard norms, a 10% decline in hematocrit, and need for blood transfusion.

a. Average blood loss for vaginal delivery, cesarean section, and cesarean hysterectomy is 500, 1000, and 1500 ml, respectively

b. Management requires understanding normal delivery blood loss, the physiologic response to and common causes of postpartum hemorrhage, and appropriate interventions

2. Physiologic response to postpartum hemorrhage

a. Pregnant patients adapt more effectively to blood loss due to increased red blood cell (RBC) mass, plasma volume, and cardiac output

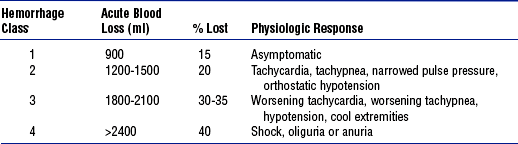

b. Early during hemorrhage, systemic vascular resistance rises to maintain blood pressure and perfusion of vital organs. If bleeding continues, vasoconstriction affords less support, which results in drops in blood pressure, cardiac output, and end-organ perfusion. Table 11-6 classifies the physiologic responses that occur at various stages of postpartum hemorrhage.

TABLE 11-6

Postpartum Hemorrhage Classification and Physiologic Response

From Gary D: Postpartum hemorrhage, New Manage Options 45(2):335, 2002.

3. Etiologic factors: Distinguished by the timing of the hemorrhage

a. Early postpartum hemorrhage (within 24 hours of delivery)

ii. Lower genital tract lacerations

iii. Lower urinary tract lacerations

b. Late postpartum hemorrhage (24 hours to 6 weeks after delivery)

a. History of precipitous or prolonged stages of labor, overstretching of the uterus, administration of medications (e.g., magnesium sulfate for pregnancy-induced hypertension), past placental retention, use of forceps or other intra-vaginal manipulations

i. Draw blood for possible cross-matching and baseline laboratory values: Hemoglobin level, hematocrit, platelet count, fibrinogen level, prothrombin time, partial thromboplastin time

ii. Estimate the volume of blood loss

iii. Identify the cause of the hemorrhage

(a) Uterine atony: Boggy, large uterus, clots, bleeding

(b) Lacerations: Firm uterus, bright red blood, steady stream of unclotted blood

(c) Hematoma: Firm uterus, bright red blood, extreme perineal-pelvic pain, unexplained tachycardia

(d) Retained placental fragments: Placenta not delivered intact, uterus remains large, absence of pain, bright red blood

5. Patient care specific to obstetric patients (see Chapter 3 for hemorrhagic shock interventions)

a. Assess the fundus: Determine the level of firmness and the placement of the fundus

b. Include estimates of the amount of lochia in intake and output assessments

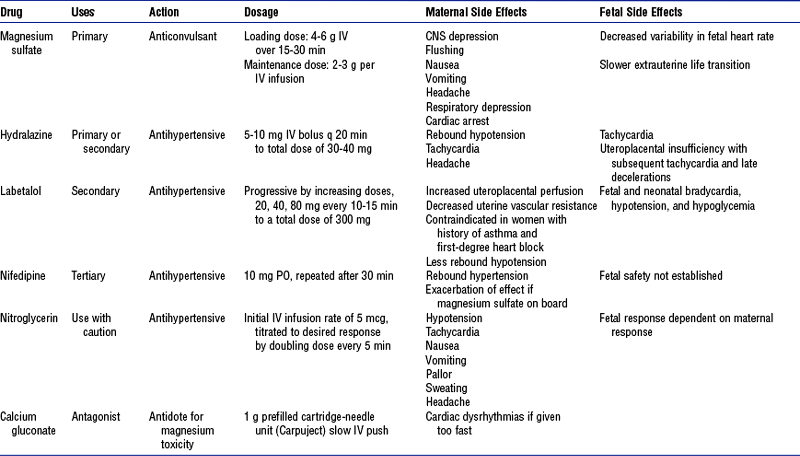

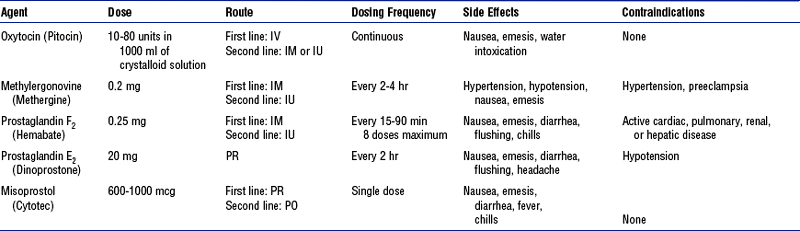

c. Administer prescribed uterotonic medications, which are the basis of drug therapy for postpartum hemorrhage. Table 11-7 lists available pharmacologic therapies for hemorrhage.

TABLE 11-7

Medications for Postpartum Hemorrhage

IM, Intramuscular; IV, intravenous; IU, intrauterine; PO, by mouth; PR, per rectum.

From Dildy GA: Postpartum hemorrhage: new management options, Clin Obstet Gynecol 4(2):330-344, 2002.

6. Evaluation: Desired patient outcomes include the following:

HYPERTENSIVE DISORDERS OF PREGNANCY

1. Definitions: Hypertension is defined as systolic blood pressure 30 mm Hg above baseline and diastolic blood pressure 15 mm Hg above baseline. In pregnancy, abnormal proteinuria is 300 mg protein or more in 24 hours.

2. Classification of hypertensive states in pregnancy

a. Gestational hypertension: Occurs in the second half of pregnancy or the first 24 hours postpartum

i. Mild: Systolic less than 160 mm Hg or diastolic less than 110 mm Hg, plus proteinuria less than 1+ on dipstick and less than 5 g in 24 hours

ii. Severe: Systolic more than 160 mm Hg or diastolic more than 110 mm Hg, plus proteinuria of more than 5 g in 24 hours

b. Preeclampsia, or pregnancy-induced hypertension (PIH): Occurs at more than 20 weeks’ gestation

i. Mild: Mild hypertension and mild proteinuria

ii. Severe: Severe hypertension and proteinuria with other symptoms including headache, visual changes, epigastric or right upper quadrant pain, and shortness of breath. May also include thrombocytopenia, pulmonary edema, and oliguria (< 500 ml in 24 hours).

a. Characterized by vasoconstriction, hemoconcentration, and possible ischemic changes in the placenta, kidney, liver, and brain

b. Intense vasoconstriction due to dysfunction of the normal interactions of vasodilatory and vasoconstrictive substances

c. Thrombocytopenia: Platelet count lower than 100,000/mm3

d. Decreased renal perfusion and reduced glomerular filtration rate

e. Hepatic system: Mildly elevated liver enzyme levels, subcapsular hematomas, or hepatic rupture

i. Chronic vasoconstriction that occurs in PIH causes fibrin deposits in hepatic sinusoids, which obstruct hepatic blood flow and alter liver function

ii. Liver swells, stretching Glisson’s capsule and producing epigastric and right upper abdominal quadrant pain

iii. Hemorrhagic periportal necrosis, subcapsular hemorrhages, and spontaneous liver rupture may occur in extreme cases. Serum liver enzyme levels rise, with aspartate aminotransferase values of 60 IU or higher (normal ≥35 IU). Jaundice and acute hepatic failure may occur.

iv. Maternal hypoglycemia is a serious prognostic indicator

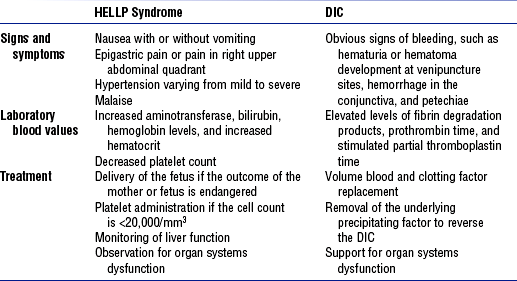

v. Risk of developing DIC is compounded: Patients with severe HELLP syndrome (all three abnormalities) are at greater risk for developing DIC than patients with partial HELLP syndrome (one or two clotting abnormalities). Despite treatment, the syndrome can escalate into DIC because the production of many clotting factors is increased in pregnancy (Table 11-9). With DIC, the clinical picture is hemorrhage and shock (see Chapter 7).

TABLE 11-9

Comparison of HELLP Syndrome and Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation (DIC)

HELLP, Hemolysis, elevated liver enzyme levels, and low platelet count.

From Bridges EJ, Womble S, Wallace M, et al: Hemodynamic monitoring in high-risk obstetrics patients: I. Expected hemodynamic changes during pregnancy, Crit Care Nurse 23:53-62, 2003.

4. Etiologic factors: Specific cause of preeclampsia is unknown (Box 11-2 lists common risk factors)

5. Patient assessment: Systematic assessments are critical to patient management; frequency is dictated by the patient’s condition and response to therapy

a. Nursing history: Medical history, past pregnancies, current pregnancy

b. Nursing examination of patient

i. Frequent monitoring for signs of cardiac decompensation (see Chapter 3), pulmonary edema (see Chapter 2), and renal failure (see Chapter 5)

ii. Hourly monitoring (deep tendon reflexes, clonus, level of consciousness) for signs of increasing CNS irritability, increasing intracranial pressure, and magnesium sulfate toxicity

iii. If the patient is antepartum, examination for fetal status and signs of placental abruption or decreased uteroplacental perfusion

c. Psychosocial and family assessment

i. Monitor RBC count, platelet count, hemoglobin level, hematocrit, coagulation profile (for hemolysis); assess for coagulation defects (increased factor VIII activity, platelet aggregation), decreased oxygen-carrying capacity, hemoconcentration or thrombocytopenia

ii. Measure serum creatinine, uric acid, blood urea nitrogen (BUN), and alkaline phosphatase levels

iii. Order liver function tests to check for elevated lactate dehydrogenase, serum glutamic-oxaloacetic transaminase, and serum glutamic-pyruvic transaminase levels

a. Only cure for PIH (regardless of gestational age) is delivery

b. Goal is to end the pregnancy with the fewest adverse effects to the mother and fetus

c. Additional management decisions may include the use of an arterial and/or pulmonary artery line for patients with severe PIH in the following situations:

i. Oliguria unresponsive to fluid challenge

iii. Hypertensive crisis refractory to conventional therapy

d. Nursing care requires accurate and astute patient assessments, strict regulation of input and output, urinary catheterization with a urometer, and comprehensive knowledge of pharmacologic therapies, management regimens, and possible complications

i. Patients who progress from HELLP to DIC need transfusions of fresh frozen plasma, platelets, cryoprecipitate, and packed RBCs. Hypotension is treated with vasopressors (e.g., dopamine). Until the patient’s condition is stabilized, the patient requires close monitoring in the ICU.

ii. Critical care nurses need to know what the signs of trouble are and how to handle complications

(a) Focus on maintaining adequate organ perfusion and watching for signs of fluid overload, bleeding, and thrombosis

(b) Administer volume replacement based on the patient’s hemodynamic values

(c) Monitor blood pressure every 5 to 15 minutes while titrating vasopressors; keep mean arterial pressure at 60 mm Hg or higher

(d) Regularly assess peripheral pulses, perfusion, and heart rate and rhythm; check intravenous (IV) and puncture sites for bleeding

(e) Administer supplemental oxygen; assess breath sounds at least every 30 minutes; respiratory difficulty could indicate fluid overload or adult respiratory distress syndrome

(f) Monitor arterial blood gas concentrations and lactate, electrolyte, BUN, and creatinine levels

(g) Watch for signs of acute tubular necrosis (e.g., decreased urinary output, increased BUN and creatinine levels, electrolyte abnormalities, metabolic acidosis)

(h) Check urine output hourly until stable, then check every 2 hours

(i) Assess vaginal discharge, bleeding at incision sites, and level of consciousness hourly while the patient’s condition is unstable and every 2 hours once stable

(j) Assess bowel sounds every 2 hours, and monitor the patient for signs of returning gut motility. Initiate an oral diet as tolerated.

(k) Continue to monitor deep tendon reflexes; watch for clonus and signs of CNS irritability. Seizures can occur up to 48 hours after delivery, so maintain seizure precautions.

AMNIOTIC FLUID EMBOLISM

1. Pathophysiology: Amniotic fluid is normally contained within the uterus, sealed off from the maternal circulation by the amniotic sac. Amniotic fluid embolism (AFE) occurs when this barrier is broken and, possibly under a pressure gradient, amniotic fluid enters the maternal venous system via the endocervical veins, placental site (if the placenta is separated), or uterine trauma site. Release of amniotic fluid containing vasoactive substances leads to pulmonary arterial spasm. Pulmonary hypertension, pulmonary capillary injury, hypoxia, hypotension, and cor pulmonale with left ventricular failure may result.

2. Etiology and risk factors: Predisposing factors for AFE include placental abruption, uterine overdistension, fetal death, trauma, tumultuous or oxytocin-stimulated labor, multiparity, advanced maternal age, and rupture of membranes

3. Patient assessment: AFE is clinically a biphasic process with the initial alterations involving central hemodynamics and oxygenation

a. Respiratory: Severe cyanosis, dyspnea, tachypnea, pink frothy sputum

b. Cardiovascular: Hypotension, shock, and dysrhythmias, but no chest pain

a. Once a presumptive diagnosis is made, supportive measures must be initiated

b. With cardiac arrest, resuscitation follows standard advanced cardiac life support (ACLS) protocols for obstetric patients

c. AFE should be managed in the ICU. Critical care nurses without obstetric expertise may become anxious when caring for pregnant patients; however, the initial priorities of care are the same as for any emergency: Maintenance of the airway, breathing, and circulation. The major difference in obstetric emergencies is the need to care for two patients.

d. Continuous fetal monitoring for signs of compromise should be performed by an obstetric nurse with expertise in electronic fetal monitoring

e. To ensure optimal uterine perfusion, the mother’s hips should be displaced to the left (which prevents the gravid uterus from compressing the inferior vena cava and decreasing venous return)

i. Administer oxygen at a concentration of 100%

ii. If a more aggressive approach is needed, provide endotracheal intubation and mechanical ventilation using a high fraction of inspired oxygen (FIo2) (>60%) and positive end-expiratory pressure (typically started at 5 cm H2O with 2- to 3-cm increments) until arterial partial pressure of oxygen (Pao2) is satisfactory

iii. Goal is to maintain Pao2 above 60 mm Hg and arterial oxygen saturation at 90% or higher

i. Position flat or in slight Trendelenburg’s position to improve venous return and CNS perfusion

ii. Provide fluid therapy, pharmacologic agents, electrocardiographic (ECG) monitoring to detect and treat arrhythmias

iii. Placement of a pulmonary artery catheter is highly recommended for monitoring cardiac output, central venous pressure, and pulmonary artery pressure and for direct access for blood samples

iv. Volume replacement with isotonic crystalloids is first-line therapy for maintaining blood pressure and avoiding overhydration in those predisposed to pulmonary edema

v. Maintain systolic blood pressure at 90 mm Hg or higher and acceptable organ perfusion (urinary output ≥ 25 ml/hr)

h. Fetal considerations: In some instances, AFE does not occur until after delivery. When AFE occurs before or during delivery, however, the fetus is in grave danger from the outset due to maternal cardiopulmonary crisis. Therefore, as soon as the mother’s condition is stabilized, delivery of a viable infant should be expedited. If resuscitation of the mother is futile, emergency bedside cesarean delivery may be necessary to save the infant.

DEFINITIONS

1. Interfacility critical care transport involves the conveyance of a critically ill or injured patient from a scene or from one clinical facility to another when the patient’s condition warrants care commensurate with the scope of practice of a specialty-trained transport nurse or physician

2. Intrafacility critical care transport involves the transfer of a critically ill or injured patient from one diagnostic, treatment or inpatient area within the hospital to another

MEMBERS OF THE CRITICAL CARE TRANSPORT TEAM

1. Interfacility transport team

a. Medical team must, at a minimum, include a specialty-trained physician or registered nurse (RN) as the primary care provider

i. At least one team member must be a registered transport nurse

ii. Program should be accredited by the Commission on Accreditation of Medical Transport Systems (CAMTS). (Refer to http://www.camts.org for a list of accredited programs.)

b. Physician or RN may be designated as the primary care provider if the following criteria are met:

i. Adequate and appropriate personnel are available to provide full coverage with physicians and RNs who are primarily assigned to the medical transport service and who are readily available within the response time determined

ii. Individual designated as the primary care provider has the appropriate state licensure

2. Intrafacility transport team

a. Personnel able to anticipate, assess, and intervene effectively if the patient experiences problems during transport. Patient whose condition is unstable or who requires a specific type of monitoring should be accompanied by staff competent in managing the instability and in interpreting and intervening appropriately based on the monitoring data. Level of care that the patient requires should be maintained in any area of the hospital. Although the CAMTS identifies staff competencies required for patient transport between hospital facilities, some of the same principles apply to staff who comprise intrahospital transfer teams.

b. RN with critical care or emergency experience and ACLS certification or its equivalent (Pediatric Advanced Life Support or Neonatal Resuscitation Program certification, or the equivalent, for an RN caring for neonatal or pediatric patients)

c. Physician familiar with the patient or with the care provided on the patient’s unit

d. Respiratory therapist if the patient is on a ventilator

e. Technician or certified nursing assistant to assist with moving or safely monitoring equipment

INDICATIONS FOR TRANSPORT

1. Interfacility: There is no universal algorithm that identifies indications for transport. Numerous associations have guidelines that recommend when a patient should be transported (see References). General indications for transport include the following:

a. Illness or injury cannot be appropriately managed at the referring facility

b. Diagnostic test, procedure, or treatment is not available at the referring facility

c. State or local regulations dictate that a particular type of patient (e.g., pediatric or trauma patient) must be cared for at a specific facility

MODES OF INTERFACILITY TRANSPORT

RISKS AND STRESSES OF TRANSPORT

1. All types of patient transport

a. Physiologic instability during transport (e.g., inadequate stabilization of the patient’s airway, breathing, and circulation; unstable cardiac rhythm)

b. Potential for further injury or death when the patient is moved

c. Inadequate patient assessment and/or monitoring during transport

d. Lack of equipment, medications, or supplies required for care or resuscitation

e. Equipment that malfunctions or is ill suited to the patient’s age, condition, or size

f. Rapid, disorganized transport due to lack of a team leader or to ineffective leadership

g. Inadequately trained transport personnel

h. Unavailability or lack of readiness of treatment area personnel to perform the procedure

i. Possibility of transport vehicle crash

ii. Long distances between treatment areas

iii. Loss of the effects of sedation or anesthesia during the transport

iv. Delayed patient arrival due to mechanical failure of the transport vehicle, traffic problems, or bad weather

i. Barometric pressure changes

ii. Hypoxia: Decreased oxygen at high altitude

(a) Hypoxic hypoxia—due to reduced FIo2 or some condition that interferes with the diffusion of oxygen from the alveoli into the systemic circulation

(b) Hypemic hypoxia—due to reduced oxygen-carrying capacity caused by conditions such as anemia, blood loss, carbon monoxide poisoning

(c) Stagnant hypoxia—caused by conditions such as shock, acute myocardial infarction, or heart failure, which slow the transport of oxygen to tissues

(d) Histotoxic hypoxia—due to interference with the tissue utilization of available oxygen caused by agents such as alcohol or narcotics, or poisons such as cyanide

c. Stresses of air and ground transport

i. Noise: Can range from 100 to 120 dB

(a) May come from sources such as rotor blades, engines, sirens, or cabin noises from equipment or loud voice communications

(b) May make it difficult to hear physiologic sounds (heart, breath, Korotkoff sounds) and equipment alarms, and to communicate verbally with the patient

ii. Temperature: Thermal changes (heat or cold) may be related to the following:

(1) Ambient temperature outside the transport vehicle

(2) Vehicle’s inability to maintain a comfortable environment

(3) Altitude—temperature decreases as altitude and barometric pressure increase

(b) Internal factors: Patient may not be able to maintain body temperature due to illness, injury, or medications, particularly neuromuscular blocking (NMB) agents

(a) Sources vary with the mode of transport

(2) Fixed-wing aircraft: Air turbulence, especially at lower altitudes

(3) Rotary-wing aircraft: Transition from main or tail rotors

(b) Can cause symptoms of mild startle reaction, including increased heart, respiratory, and metabolic rates

iv. Motion (acceleration, turning or banking, gravitational forces, visual field motion)

a. Insufficient number of staff accompanying the patient

b. Inadequate transport team staff mix to meet the patient’s needs during transport

c. Unanticipated delays related to elevator or electrical power failure

d. Lack of communication between the originating and receiving areas regarding the transport

OVERRIDING PRIORITIES IN PATIENT TRANSPORT

1. Paramount determinants in decisions regarding patient transfer and transport

a. Health, well-being, and safety of the patient require the following:

i. Securing of the patient for transport

ii. Securing of all equipment and supplies

iii. Possible restraint of the patient to avoid harm to self or others, via one or more of the following means: Pharmacologic restraint (e.g., NMB agents), pharmacologic sedation, physical restraint

b. Health, well-being, and safety of the transport team require the following:

2. Safety of the patient and transport team may require refusal to transport due to

b. Maintenance issues: Unsafe maintenance of an aircraft or ground vehicle (e.g., vehicles not properly inspected according to the manufacturer’s recommendations or state or federal regulations)

c. “Program shopping”: One program or facility refuses the transport due to weather and the referring entity attempts to find another program to undertake the transport despite unsafe weather conditions

PREPARATION FOR TRANSPORT

1. Select the appropriate transport service: Determined by the needs of the patient to be transported

c. Critical care transport team

d. Specialty team (e.g., neonatal, pediatric, perfusion, respiratory care)

2. Select the equipment for transport: Desired attributes (see Warren et al., 2004, for equipment suggested by the American College of Critical Care Medicine)

a. Indicated by the patient’s illness or injury

b. Adapted for the transport setting

c. Able to be safely restrained in the transport vehicle

e. Redundant, multifunction (e.g., noninvasive and invasive blood pressure monitoring, end-tidal CO2 and pulse oximetry)

g. Sufficient battery life for transport with backup power source

h. Able to withstand the stresses of transport, including vibration, temperature changes, accidental dropping, use by multiple persons

3. Secure equipment and supplies for transport

a. Following items are suggested for inclusion:

i. Monitor, defibrillator, external pacemaker

ii. Pulse oximeter and end-tidal CO2 monitor

iii. Advanced airway equipment (age appropriate)

iv. Transport ventilator or bag-valve device

vii. Emergency medications (for ACLS, NMB, sedation, analgesia)

viii. IV supplies: Fluids, needles, start kits (in case IV is lost during transport), infusion pumps

ix. Any other device or medication the patient may require to maintain vital functions

b. Ensure that the equipment and supplies are adequate to last for transport to the diagnostic or treatment area, for completion of the procedure, and, when warranted, for the return of the patient to the unit

4. Assess and prepare the patient for transport

i. Rapid primary survey with immediate interventions to secure and maintain a patent airway

ii. Assessment of the patency of any in-place airway device such as an endotracheal tube

i. Determine if altitude may place the patient at risk (e.g., a patient with thoracic trauma may need a chest tube for transport)

ii. Ventilator-dependent patient should be given a trial run using the transport team’s equipment

iii. In general, all patients are given oxygen during transport

ii. Establishment and maintenance of venous access

iii. Insertion of other invasive lines as indicated

iv. Anticipation of IV fluid and medication needs

v. Securing of the necessary circulatory support equipment (e.g., intraaortic balloon pump, left ventricular assist device)

i. Altitude can increase the risk of vomiting; determine whether a nasogastric tube should be inserted to prevent aspiration

ii. Motion can cause nausea and vomiting; administer prophylactic antiemetics, as ordered

e. Splinting: To prevent further injury and enhance patient comfort

i. Estimate the patient’s probable needs for analgesia

ii. Determine whether the patient has received an NMB agent; if so, plan to closely monitor the need for analgesia and/or sedation

g. Wound care: Perform an initial appraisal; reinforce for transport if indicated

h. Safety: Assess the potential of the patient to harm self or the transport team; restrain if necessary

5. Notify the receiving unit or procedure area

a. Time the unit or area should expect the patient to arrive

b. Equipment the patient will be using

c. Equipment that will be required to maintain the patient during the procedure

6. Prepare the family for interfacility transport

a. Always allow the family to see the patient before transport

b. Explain to the family why the patient must be transferred

c. Identify who will be caring for their family member during transport

d. Provide directions to the receiving facility

e. Remind the family to follow all traffic laws while in transit to the receiving facility

7. Other interventions recommended before intrafacility transport

a. Suction the endotracheal tube or other airway device, as indicated

b. Attach the patient to the transport ventilator; assess tolerance before leaving the unit

c. Ensure the patency and flow rate of IV sites and medications

d. Assess the patient’s neurologic status

e. Administer sedatives, analgesics, and any other medications that may be required during the transport. Remember that movement can cause the patient severe pain and anxiety.

f. Ensure that patients who require monitoring equipment will continue to be monitored during transport whenever possible (e.g., via wireless or battery-powered equipment)

g. Explain the need for transport to the patient and family

h. Ensure that adequate personnel are available to safely move the patient

i. If there is a procedure nurse, notify the nurse with a report that includes patient diagnosis, current medications and treatments, and planned interventions or procedures

PATIENT CARE DURING TRANSPORT

1. Patient access: Team members are positioned so they can assess and manage the patient

a. Airway equipment, including suction device, is readily accessible

b. All IV lines are visible; at least one is accessible for medication administration

c. All intake and output (urinary, gastric, chest tube, other), as well as responses to IV infusions and medications, are monitored

d. All tubes and drainage systems are secured to reduce the possibility of dislodgement

e. All transport monitors and equipment are placed within the team’s line of sight. Visible alarms should be used.

f. If the patient requires chemical or physical restraint for safe transport, ensure that the patient receives adequate sedation, analgesia, and environmental control

g. Team needs to keep in mind that movement, noise, temperature changes, and fear can increase the patient’s pain and make its management more challenging

LEGAL AND ETHICAL ISSUES RELATED TO TRANSPORT

1. Emergency Medical Treatment and Active Labor Act (EMTALA)

a. All patients who come to an emergency department should be medically screened to determine whether a medical emergency is present

b. Condition of a patient with a medical emergency must be stabilized within the capabilities of the emergency department

c. If the patient must be transported for care, the receiving hospital must accept the patient, if a bed and personnel are available

d. Referring hospital must send all copies of medical records, diagnostic studies, informed consent documents, and physician transfer certifications

e. Patient must be transported by qualified personnel, with appropriate equipment, and via the most suitable mode of transport

3. Written policies and procedures

a. Must include the indications for transport, facilities to which patients may be referred, and procedure for preparing patients for transfer and transport

b. Should specify whether a family member may or may not accompany the transport team

a. Quality improvement parameters

b. Regulations of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA): Appropriate use of patient information to improve care

5. Decision to transport or not to transport

a. No-transport decisions: Transport team needs established policies for “no transport” or the ability to consult with medical directors when making this decision

b. Family consultation: When possible, the patient’s family should be included in decisions not to transport

i. Patients who have had a cardiopulmonary arrest must be carefully assessed to determine the benefits of transport, because the effectiveness of cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) is compromised during transport

ii. In addition, the transport team may be placed at risk by not being adequately restrained while performing CPR, by sustaining needle sticks when administering drugs during CPR, and by being exposed to blood or body fluids during CPR

Pediatric Patients

1. Children—a unique population: Children are not small adults. Differences in size, anatomy, and developmental level result in unique responses to illness and technical challenges. Nurses who care for children in an adult critical care area need basic competency in developmental care, which involves first identifying the child’s developmental level and then planning care around that level. This section provides an overview of assessments, developmental levels, and anatomical differences that may influence nursing care of the critically ill child.

2. Guidelines for assessment of children

a. Whenever possible, allow the parents to hold and be with their child

b. Before touching a child, measure vital signs and complete visual assessments. Children may cry or become frightened, so that assessment findings are altered.

c. Speak in terms the child can understand based on developmental level

d. Allow the child to touch and play with medical equipment (e.g., stethoscope) used for assessment

e. Whenever possible, offer the child choices. For example, does the child want the IV line in the hand or the arm?

f. Offer positive reinforcement and give rewards, whenever possible

g. With a mature child, work together with the child to plan his or her care

h. Always tell the truth. Building a trusting relationship requires this. If something is going to hurt, do not tell the child that it won’t.

i. Listen to the parents. They are the ones who know the child best and can more readily discern subtle changes in the child’s condition.

i. Fear separation from caregivers. Allow the parents to be at the bedside as much as possible.

ii. Touch is very important. Allow the parents to hold the child; if that is not possible, encourage the parents to stroke and touch the child.

iii. Infants like to be swaddled. Keep their hands and arms at midline.

iv. Infants fear strangers. Insofar as possible, provide consistent caregivers.

v. Infants fear pain and may cry when approached, anticipating that something may hurt. Use analgesics as needed.

vi. As infants get older, they will grab at medical equipment within their reach. Although therapeutic play is beneficial and usually safe, it is important to keep dangerous items out of reach.

vii. Infants need comfort measures. Encourage the parents to bring the child’s favorite blanket or crib toy to the hospital. Hold the child awhile after procedures are completed.

viii. Infants have a need for deep sleep. Insofar as possible, cluster procedures and care to maximize periods of uninterrupted sleep.

ix. Because infants are not able to tell caregivers what is wrong, additional tests may be necessary to reach a diagnosis

x. Presence of strong visual and auditory stimuli may increase stress to infants, so lights and noise should be minimized to promote rest

xi. Restraints should be used only to keep a child safe

xii. Bronchiolitis due to respiratory syncytial virus frequently causes apnea and may require intubation

xiii. Diagnoses most frequently seen in this age group are sepsis, congenital heart disease, hypoglycemia, and bronchiolitis

b. Toddler (ages 1 to 3 years)

i. Toddlers fear separation from their caregivers. Allow caregivers to remain at the bedside as long as feasible.

ii. Toddlers frequently use the word no to gain control and autonomy. Toddlers need to be offered choices when these exist. That does not mean that they can refuse necessary care, but, for example, they can decide which arm to use for drawing blood.

iii. Toddlers have an intense fear of mutilation as well as a magical imagination. They may fixate on having adhesive strips over all needle sticks because they fear their blood could come out through those holes. For these reasons, caregivers need to use concrete terms and incorporate play when preparing toddlers for procedures.

iv. Toddlers have a strong sense of curiosity. Caregivers need to perform a complete safety check of the environment to ensure that they cannot delve into anything that might harm them.

v. Toddlers take things very literally, so explanations need to be in simple terms to avoid creating unwarranted fears and misinterpretation

vi. Toddlers need their normal routines followed whenever these can be preserved. Parents can identify routines important to their child.

vii. Toddlers need to be told the truth to develop trust in caregivers

viii. Toddlers do not understand the concept of time, so they do not distinguish between 2 hours and 2 weeks. As a result, 2 days might be better described as “two wake-ups.”

ix. Diagnoses most commonly seen in this age level are head trauma, near drowning, accidental ingestion of harmful substances, asthma, and seizures

c. Preschooler (ages 3 to 5 years)

i. Preschoolers are offended by lies and lose trust in adults rapidly, so do not say that something will not hurt if it will

ii. Preschoolers have great imaginations. The truth (no matter how bleak) in simple words is often less frightening than what they are imagining. This also needs to be remembered when dealing with the critically ill child’s siblings.

iii. Preschoolers share toddlers’ fears of bodily harm and mutilation. They may also fear that they are in the hospital because they have done something wrong or “bad.”

iv. Preschoolers are afraid of the dark and of being alone. Adjusted lighting and familiar faces nearby can help allay these fears.

v. Preschoolers fear the unknown and want to be in control of the environment. Their developing sense of self can be supported by always preparing them for procedures, by explaining what will happen in simple terms, by incorporating play into this preparation, and by allowing them to ask questions.

vi. Preschoolers may be able to help in some of their own care

vii. As with toddlers, preschoolers do not fully understand the concept of time, except for familiar distinctions such as “lunchtime”

viii. When hospitalized, preschoolers may regress to behaviors such as thumb sucking or bed wetting

ix. Preschoolers can easily misinterpret conversations and unfamiliar terms. Staff can minimize this problem by avoiding discussions about the child’s condition in locations where they might be overheard.

x. Diagnoses most often seen among preschoolers are trauma and dehydration related to influenza

d. School-aged child (ages 5 to 12 years)

i. School-aged children are concrete, operational thinkers

ii. They need to be prepared in advance for procedures, using body diagrams or models to explain what is going to happen

iii. Encourage these children to ask questions. They understand cause and effect relationships, so treatments or medications can be explained in terms of how these help them to recover.

iv. They fear loss of control, so provide choices when possible

v. They fear mutilation and understand that death is final

vi. Privacy can be extremely important. They understand that their bodies are different and do not want others to see them undressed.

vii. They want to help, to be involved; enlist their participation in care

viii. Friends are very important in their lives. Letters from friends, family, and classmates are encouraged.

ix. Diagnoses most often seen for this age group are arteriovenous malformation and trauma

e. Adolescent (ages 12 to 21 years)

i. When communicating with adolescents, it is important to be straightforward, scrupulously honest, and nonjudgmental to establish trust. Unless they feel trust, they will not be open, honest, or cooperative with caregivers; they need to know that caregivers are on their side.

ii. Exerting independence is important to adolescents, who may be noncompliant with care to express this need

iii. It is important to involve adolescents in decision making that affects their care so they can maintain a sense of control

iv. Adolescents require advance preparation for events related to their care

v. Body image is highly important. Disfiguring conditions or injuries can be especially traumatic and demand considerable therapeutic intervention.

vi. Privacy, modesty, confidentiality, and acceptance as a person are priorities to adolescents that caregivers must respect

vii. Adolescent “acting-out” behaviors may reflect relationship problems with parents, peers, or girlfriends or boyfriends that may be difficult for others to see or fully appreciate

viii. It is important to ask about drug, alcohol, and tobacco use. Adolescents may not volunteer this information, and such use could impede their care.

ix. Diagnoses most often encountered among adolescents are trauma and intentional ingestion of substances

4. Anatomical differences between children and adults

i. Children have a higher center of gravity, so are more prone to falls

ii. They have a relatively larger head and weaker neck muscles. In a car crash or long distance fall, the head may act like a missile and propel the body with greater velocity and subsequently greater force on impact and whiplash.

iii. Infants are especially vulnerable to head trauma because of their thin craniums and open fontanelles (until about 18 months of age)

iv. They have lax ligaments and can have spinal cord injury without radio-graphic abnormality

v. Their bones and ligaments are more pliable. In chest trauma, ribs may not be fractured, yet underlying organs can be damaged.

vi. Motor skills may not be fully developed, which makes them more vulnerable to falls and injury

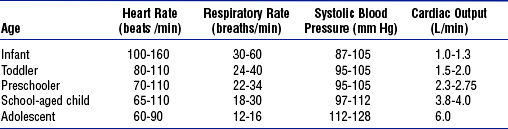

vii. Normal ranges of vital signs differ by age (Table 11-10)

i. Infants are obligate nose breathers; they can have trouble breathing if their nares are blocked by mucus or a nasogastric tube

ii. In children the tongue is disproportionately larger and can occlude the airway

iii. Airway cartilage is soft, particularly in the larynx. Care must be taken to avoid hyperextension and hyperflexion of the neck, because either could cause airway occlusion.

iv. Larynx is higher and more anterior, which makes children more prone to aspiration or airway obstruction. It can also make intubation more difficult.

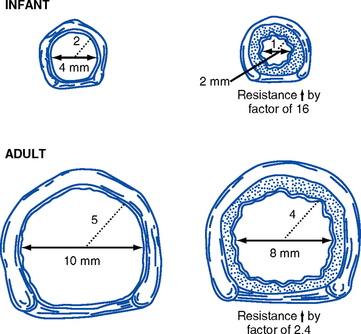

v. Tracheal diameter is proportional to body size. As a result, small degrees of swelling can occlude the airway of a small infant (Figure 11-1).

vi. In children younger than 8 years of age, the cricoid cartilage is the narrowest portion of the trachea. An inappropriately large endotracheal tube could cause tracheal swelling and damage.

vii. Tracheal length is shorter, so there is a risk of intubating the right mainstem bronchus

viii. Diaphragm is positioned more horizontally. Children use diaphragmatic breathing for ventilation, so air in the stomach can raise the diaphragm and compromise lung capacity.

ix. Chest wall is more pliable in children. They could have underlying organ damage in trauma that may be missed because of lack of obvious external injury.

i. Differences in pediatric heart rate and blood pressure are important to note (see Table 11-10)

ii. Children increase their cardiac output primarily by increasing their heart rate. Vasoconstriction may be seen, but only when fluid loss is great. Decreased blood pressure can be a very late sign of shock.

iii. Blood volume depends on the size of the child

iv. Children compensate extremely well by maintaining blood pressure. When a child’s blood pressure begins to fall, the end is near.

d. Thermoregulatory differences

i. Children, especially infants, have a large surface area–to–volume ratio and less subcutaneous tissue. As a result, they lose heat to the environment more readily and are more susceptible to poisoning by chemicals that can be absorbed through the skin.

ii. Cold stress is important to avoid because it can cause significant energy and oxygen consumption, increased metabolism, and hypoglycemia

i. Skull of the infant or young child is thin and offers little protection to the brain

ii. Children are more prone to head injuries because the head diameter is relatively larger than that of adults

iii. In children, head trauma is more often associated with hemorrhage related to shear forces and intracranial swelling

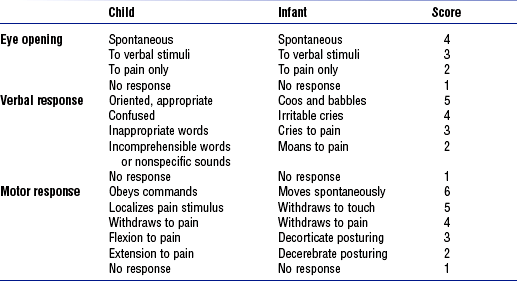

iv. Glasgow Coma Scale assessments are modified for infants and children (Table 11-11)

i. Children have a protruding abdomen, which may help protect them from major pelvic injuries

ii. Organs injured most often in children are the liver and spleen

iii. Abdominal muscles are thinner and weaker, and afford less protection to underlying organs

iv. Pelvis is more anterior, and thus more vulnerable to impact, than in the adult

5. Summary: Children are not just small adults. When they are admitted to an adult ICU, critical care nurses need to plan and provide care based on the physiologic and psychologic attributes summarized here. It is important that nurses have some basic competency in caring for children. The eight patient characteristics in the Synergy Model are different in children depending on their developmental stage because they do not have the ability to care for themselves. When nurses have the basic competencies to care for children and they understand children’s characteristics, optimal patient outcomes can result.

GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS

a. Assessment of the patient’s level of anxiety, agitation, and sedation, and response to sedative medication

b. Altered response to drugs due to underlying medical conditions

c. Tolerance to medication due to prior experience with the drug or the length of time it was received

i. Overdose of sedative due to individual variability or drug interaction

ii. Delayed elimination due to comorbidities, age, liver or kidney dysfunction

e. Withdrawal symptoms: May cause agitation or confusion

i. From drugs the patient was previously taking

ii. From sudden cessation of sedative or opioid use, which can cause a return of agitation; early symptoms of opioid withdrawal include salivation, yawning, diarrhea

f. Drug interactions of sedatives with other medications the patient is receiving

i. Anxiety, agitation, increased metabolic demand

ii. Tachycardia, hypertension, myocardial ischemia, dysrhythmias

i. Delayed emergence, delayed weaning from ventilator

ii. Pressure injury, venous stasis, muscle atrophy

iii. Increased tests, ICU and/or hospital length of stay, costs

c. Indications for sedation in the ICU

i. Anxiety (Park, Coursin, Ely, et al, 2001)—feelings of nervousness, apprehension, or fear

ii. Agitation (McGaffigan, 2002)—a more extreme form of excessive, uncontrolled, or irrational activity commonly associated with increased muscle tone and increased catecholamine levels

iii. Delirium (Bixby and Picard, 2005)—characterized by confusion, disordered speech, and hallucinations; an acute, reversible organic mental syndrome

iv. Pain—from injuries, surgery, trauma, procedures, preexisting conditions, and so on

ii. Use quantitative tools to assess sedation and pain

iii. Choose the right drug or combination of drugs; reevaluate the need for sedation

i. Before sedating, rule out the need for analgesia and treat reversible physiologic causes

ii. When the patient can communicate, assess via a quantitative scale; use the patient’s report of pain as the basis for treatment

iii. When the patient is unable to communicate, assess via subjective criteria (e.g., facial expressions, posturing, vital signs)

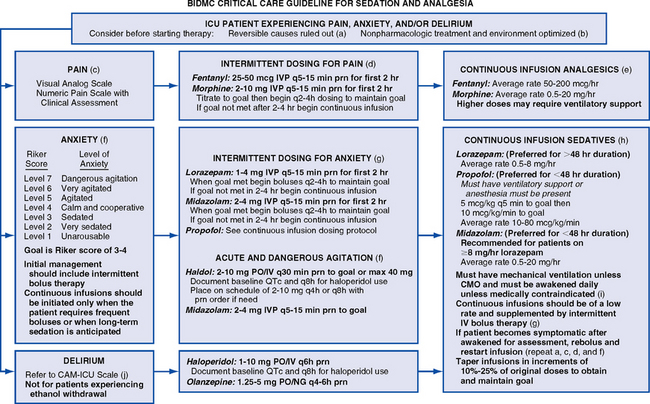

a. Establish a sedation goal and ensure that it is regularly redefined and documented

b. Use a validated sedation assessment scale, a subjective measure

c. Keep in mind that sedation scales do not assess anxiety, pain, or sedation in paralyzed patients

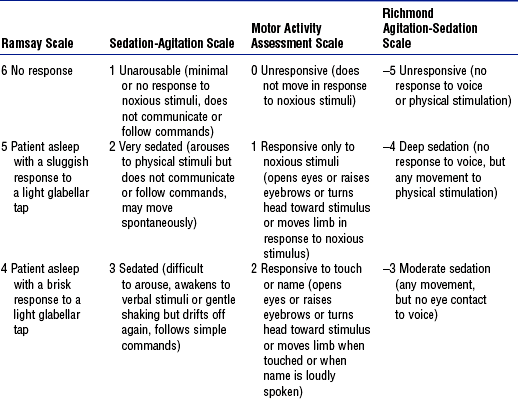

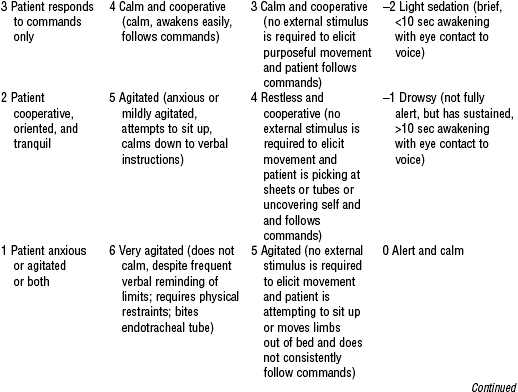

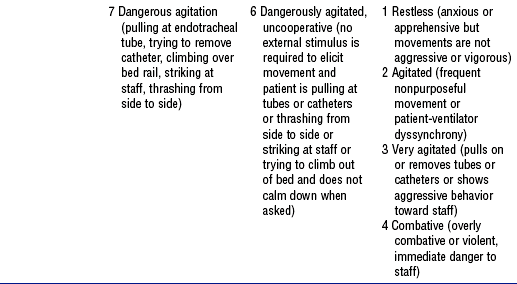

d. Sedation scales in current use: See Table 11-12

TABLE 11-12

Sedation Assessment Scales for Adult Patients

From Consensus conference on sedation assessment: a collaborative venture by Abbott Laboratories, American Association of Critical-Care Nurses, and Saint Thomas Health System, Crit Care Nurse 24(2):35, 2004. Data from Ramsay MA, Savege TM, Simpson BR, et al: Controlled sedation with alphaxalone-alphadolone, BMJ 2:656-659, 1974; Devlin JW, Boleski G, Mlynarek M, et al: Motor Activity Assessment Scale: a valid and reliable sedation scale for use with mechanically ventilated patients in an adult surgical intensive care unit, Crit Care Med 27:1271-1275, 1999; Riker RR, Fraser GL, Cox PM: Continuous infusion of haloperidol controls agitation in critically ill patients, Crit Care Med 22:433-440, 1994; Sessler CN, Gosnet MS, Grap MJ, et al: The Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale: validity and reliability in adult intensive care unit patients, Am J Respir Crit Care Med 166:1338-1344, 2002; Ely EW, Truman B, Shintani A, et al: Monitoring sedation status over time in ICU patients: reliability and validity of the Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale (RASS), JAMA 22:2983-2991, 2003.

ii. Riker Sedation-Agitation Scale (SAS)

iii. Motor Activity Assessment Scale (MAAS)

iv. Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale

v. Other scales: Luer scale; Shelly scale; COMFORT scale (tested only in children); Vancouver Interaction and Calmness Scale (VICS)—scores up to 30 for interaction (communication) and up to 30 for calmness (calm to pulling at lines); Faces Anxiety Scale

vi. New sedation assessment scale under development (including validity and reliability testing) by Abbott, American Association of Critical-Care Nurses, and the Saint Thomas Health Systems Expert Panel (DeJong MJ: Personal communication, October 11, 2004)

e. Objective measures of assessment

i. Vital signs, such as blood pressure and heart rate—not specific or sensitive

ii. Electroencephalography (EEG), auditory evoked potentials

iii. Lower esophageal contractility

iv. Bispectral index monitor (BIS)

(a) Measures effects of sedatives on the brain and consciousness

(b) Consists of a single sensor with several electrodes attached to the forehead

(c) BIS value (0 to 100) is an empirical, statistically derived number that correlates with the hypnotic level of the patient

(1) BIS value above 95 indicates full consciousness

(2) BIS value below 60 indicates reduced likelihood of consciousness

(d) Useful with deeply comatose patients or those under NMB; scores may be artificially elevated by muscle-based electrical activity in patients not under NMB

(e) BIS monitoring not completely validated as useful in the ICU, but may be a promising tool in the future

a. Benzodiazepines: Produce amnesia, hypnosis, and anxiolysis, but not analgesia

(a) Recommended for short-term use only because it causes unpredictable awakening when infusions continue longer than 48 to 72 hours

(b) Midazolam or diazepam should be used for rapid sedation of the acutely agitated

(c) Onset of action after IV dose, 2 to 5 minutes; half-life, 3 to 11 hours

b. Propofol: Produces hypnosis, anxiolysis, less amnesia than benzodiazepines, no analgesia

i. IV sedative-hypnotic general anesthetic; approved for sedation of intubated adults on mechanical ventilation in the ICU

ii. Rapid onset of action (1 to 2 min); short persistence of action once discontinued; half-life, 26 to 32 hours

iii. Preferred sedative when rapid awakening is important

iv. Can elevate triglyceride levels; monitor after 2 days of infusion

v. Add total caloric intake from lipids contained in medication in nutritional support orders

vi. Requires strict aseptic technique for administration because it contains absolutely no preservative

c. Opioids: Provide analgesia and anxiolysis

i. Recommended for IV use in the critically ill: Fentanyl, hydromorphone, morphine

ii. Scheduled doses or continuous infusion preferred over “as needed.” Patient-controlled analgesia can be used if the patient is able to understand and operate the equipment

iii. NSAIDs or acetaminophen may be used as adjuncts to opioids. Ketorolac use should be limited to a maximum of 5 days.

d. α2-Agonists: Provide hypnosis, anxiolysis, and analgesia, but no amnesia

(a) Inhibits norepinephrine release from central and peripheral presynaptic junctions

(b) Enables use of lower dosages of opiates to achieve comfort

(a) Selective α2-agonist that inhibits the release of norepinephrine

(b) Has sedative and analgesic effects without causing respiratory depression

(c) Patients remain sedated when not disturbed, but arouse easily with gentle stimulation

(d) Approved for short-term use (<24 hours)

(e) May produce transient elevations in blood pressure, bradycardia, and hypotension

6. Nonpharmacologic methods to decrease anxiety

a. Reorientation and validation of anxiety

b. Use of cards with phrases to aid communication with intubated patients unable to speak

c. Soft lighting, restful music, pleasant room design and color, pictures from home

d. Music therapy, massage, therapeutic touch, pet therapy, liberal visitation

a. Fluctuating mental status, disorganized thinking, altered level of consciousness, with or without agitation

a. Sleep promotion is imperative for patients in the ICU, although those on high dosages of sedatives demonstrate atypical sleep patterns

b. Sedative dose should be titrated with the end point defined and administration interrupted daily to reassess the patient and minimize the effects of prolonged sedative use

c. Withdrawal effects can occur if opioids, benzodiazepines, or propofol is used for longer than 7 days

d. Use of sedation guidelines, an algorithm, or a protocol is recommended (Figure 11-2)

9. Competency of the RN administering sedatives (these requirements are equally applicable to nurses administering procedural sedation)

a. Receipt of specialized instruction related to the use of sedatives and analgesics

b. Possession of the following required competencies (Synergy Model—nursing competencies based on patient needs):

i. Knowledge of the relevant anatomy, physiology, pharmacology, recognition and management of cardiac dysrhythmias, CPR procedures

ii. Ability to assess total patient care requirements