Chapter 24 Craniopharyngiomas

Craniopharyngiomas are tumors of neuroepithelial origin that arise from squamous cell rests found along the path of the primitive craniopharyngeal duct. Their incidence ranges between 0.5 and 2.5 per 100,000 person years and does not vary by sex or race. Craniopharyngiomas account for 1.2% to 4.6% of all intracranial tumors (Central Brain Tumor Registry of the United States). They exhibit a bimodal distribution, first peaking during childhood (5–14 years) and later peaking in adults ranging from 50 to 74 years; they comprise 5% to 10% of pediatric brain tumors and 1% to 4% of adult brain tumors.1–4 Craniopharyngiomas have a growth pattern that is often in close proximity to the pituitary infundibulum, and can occur within the sella, suprasellar space, or third ventricle, frequently spanning these spaces. These tumors tend to involve a number of neural structures, including the optic nerves, internal carotid arteries (ICAs), and pituitary gland, causing a variety of symptoms. Common clinical presentations include visual dysfunction with symptoms of chiasmatic as well as postchiasmatic compression, hypothalamic dysfunction with behavioral changes ranging from alterations in eating patterns, to apathy, and even obtundation and pituitary dysfunction, often manifesting as hypopituitarism.

Classification

Several authors who attempted to radiographically classify craniopharyngiomas include Rougerie, Pertuiset, Konovalov, Steno, Hoffman, Samii, and Kassam.5–11 Although none have been universally adopted, these classifications all share the principle of subdividing lesions along the length of extension in the primary vertical axis; the resulting relationship is with the optic chiasm and the third ventricular floor immediately posterior to it.

Anatomy

Another important limiting factor during surgical resection is the close apposition of craniopharyngiomas to the pituitary infundibulum. This opposition has led some to argue that gross total resection cannot be achieved without the section and removal of the involved part of the infundibulum. Although this point remains contested, the morbidity of sacrificing the infundibulum is significant, particularly in pediatric patients.12–19 Diabetes insipidus and hypopituitarism after injury to the infundibulum can impact both the physical and mental growth of patients and limit their daily functional capacity.

Treatment Decision Making

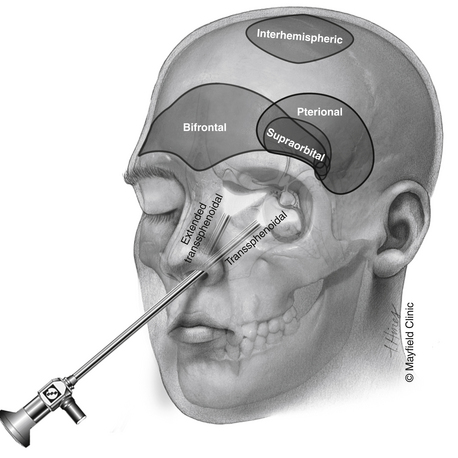

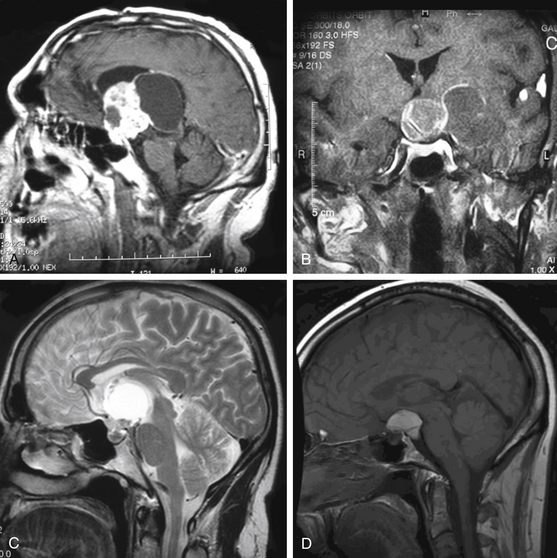

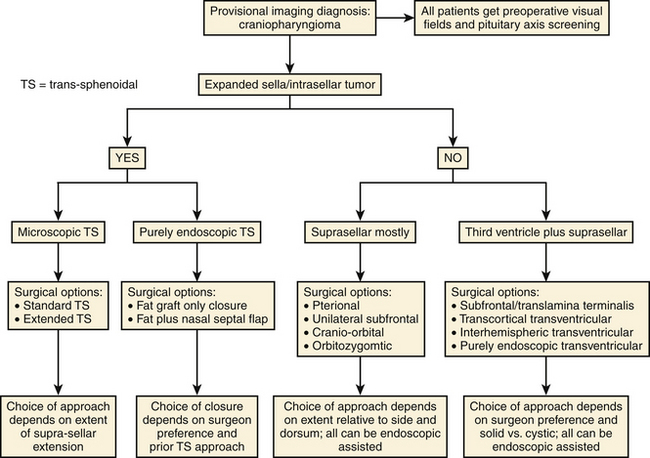

Although most patients undergo both surgical and radiation treatments, a number of questions need to be addressed on an individual level. Choice of surgical approach depends primarily on the extent of the lesion along the vertical axis (Fig. 24-1). Lesions that are purely intrasellar are preferably approached through a trans-sphenoidal approach. Microscopic or endoscopic corridors have been well described and mimic the approach to pituitary adenomas. Because intrasellar lesions are often cystic, obliteration of the tumor cavity with fat may not be indicated unless a cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leak is manifested intraoperatively, effectively allowing for a prolonged outlet that can delay or prevent future reaccumulation of fluid within the cavity. The trans-sphenoidal route can also be used successfully in the presence of significant suprasellar extension in mostly cystic lesions. The recent development of expanded endoscopic trans-sphenoidal approaches to the sella make the resection of the cyst wall possible when vascular adherence is not a significant issue.

Transcranial routes to the suprasellar space range from a supraorbital corridor to the pterional approach (with or without an orbital or orbitozygomatic osteotomy) to the bifrontal craniotomy. Although each one of these approaches provides a similar exposure to lesions in the suprasellar space, they differ in several important ways. The supraorbital craniotomy, which minimizes soft-tissue morbidity and creates a shorter overall incision, is limited by the size of the frontal sinus. Violation of the frontal sinus through the supraorbital approach can cause a CSF leak that is challenging to fix or a rotation periosteal flap is difficult. Additional limitations of the supraorbital craniotomy include the limited vertical exposure and difficulty with effective brain retraction.

Surgical Techniques

Trans-Sphenoidal/Expanded Trans-Sphenoidal Approach

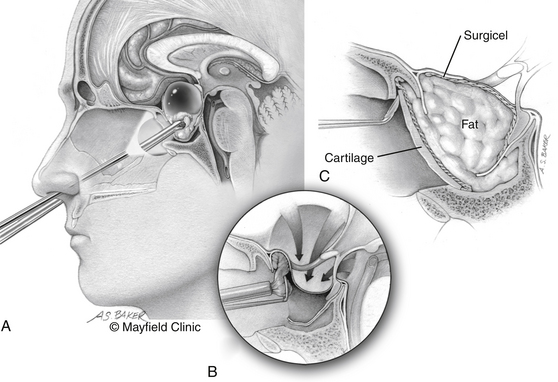

The patient is positioned supine; the head in the “sniffing” position allows for elevation above the level of the heart and drainage of bloody material inferiorly away from the surgical field. The traditional trans-sphenoidal approach through a microscopic or endoscopic approach can be used. Intrasellar tumors and mostly cystic craniopharyngiomas even with a significant suprasellar extension are excellent candidates for this approach (Fig. 24-2).

The expanded trans-sphenoidal approach requires significant bony removal superiorly past the tuberculum. Importantly, at the beginning of an expanded trans-sphenoidal approach, consideration should be given to raising a nasoseptal mucosal flap, which will be used during closure.20 Visualization of the superior aspect of the lesion and its relationship to the undersurface of the optic chiasm is feasible with debulking of the tumor. The perforating vessels and the plane with the optic apparatus need to be sharply dissected under direct vision. However, present endoscopic instrumentation creates an obstacle to effective dissection in many patients.

Although a watertight closure of expanded trans-sphenoidal approaches remains elusive, significant steps have been made during the past several years. Simple fat obliteration proves to be inadequate reconstruction. Multilayer reconstructions and the use of vascularized pedicled mucosal flaps have been promising as an effective reconstruction that can prevent leaks. Use of specialized clips that attempt direct dural reapproximation is an obvious improvement, yet technically very challenging. Deployment of inflatable balloons within the sphenoid sinus can augment the reconstruction. Lumbar subarachnoid drains for temporary CSF diversion offer mechanical advantages but must be balanced by their risk of potential complications, compression of neurovascular structures for the former, and development of pneumocephalus for the latter.

Bifrontal Craniotomy

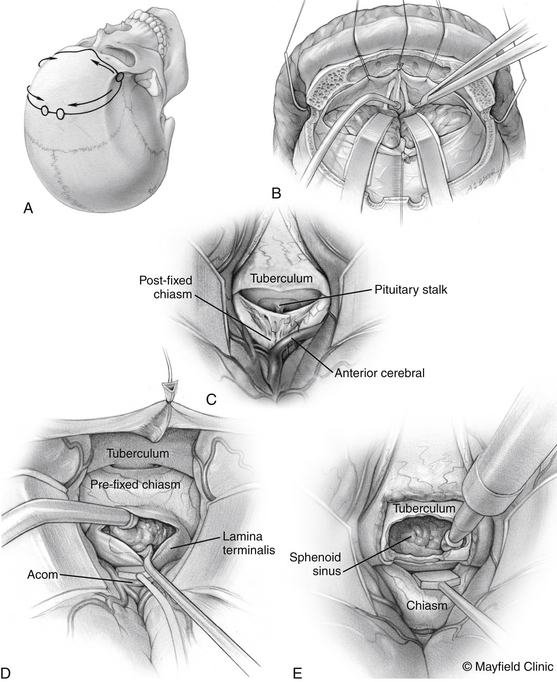

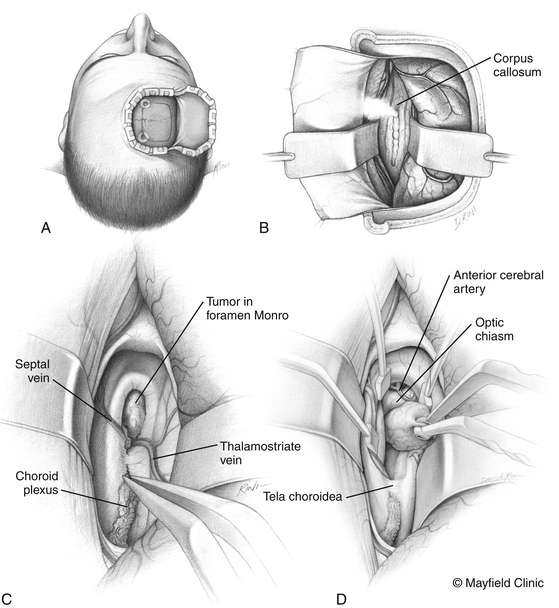

The patient is positioned supine with the head slightly extended in three-point pin fixation in the Mayfield clamp. Frameless stereotactic guidance is a useful adjunct for accurate localization of the lesion. A bifrontal incision is marked behind the hairline. Ensuring that the lateral limits are close to the zygomas bilaterally then limits the pressure on the skin flap and avoids flap ischemia. Burr holes are placed on either side of the superior sagittal sinus, approximately 5 cm above the nasion and laterally superior to the keyhole, just lateral to the superior insertion of the temporalis muscle, which is elevated in a limited fashion. The inferior bony cut is preferably made just superior to the frontal sinus; however, transgression of the sinus can be fixed easily with the use of a rotational pericranial flap. The dura is opened in a horizontal incision inferiorly and the superior sagittal sinus is divided with medium vascular clips. The falx is incised and the anterior interhemispheric space is explored (Fig. 24-3).

Pterional Craniotomy

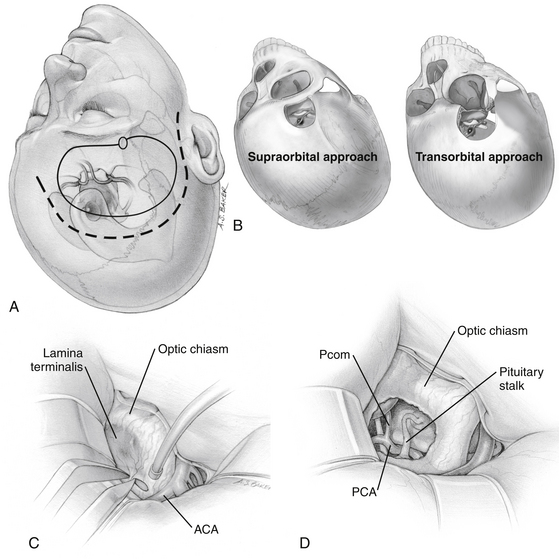

The traditional frontotemporal or pterional craniotomy is perhaps the most widely used approach for the treatment of craniopharyngiomas. Reduction of the sphenoid wing is a standard part of this approach because it improves exposure superiorly. Once the basal cisterns are opened, there are two major corridors for lesion resection: the subchiasmatic corridor between the two optic nerves and the opticocarotid corridor between the lateral aspect of the ipsilateral optic nerve and ICA (Fig. 24-4).

The supraorbital craniotomy and its transorbital variant provide a similar degree of exposure with somewhat limited soft tissue dissection (Fig. 24-4B). The temporalis muscle is mobilized to a much lesser degree. With the incision is linear within the eyebrow, there is little need for subcutaneous dissection. The bone flap, which averages 3 × 2 cm, provides adequate access to most lesions in the parasellar space. Care should be taken to avoid injury to the frontalis branch of the facial nerve along the lateral aspect of the incision. The use of frameless stereotactic guidance is recommended to prevent violation of the lateral recess of the frontal sinus. Reconstruction of the sinus from this approach is limited and may result in a transnasal CSF leak that can prove difficult to seal. In our practice, an extensive lateral recess of the frontal sinus is a contraindication for this approach.

Transventricular Approach

The transventricular approach is an important surgical corridor for lesions that are primarily third ventricular in location. Although this can be used in most lesions that occupy the third ventricle, the presence of obstructive lateral ventriculomegaly makes this the preferred approach for such lesions. Access to the lateral ventricle can be achieved preferably in a transfrontal fashion in the presence of dilated lateral ventricles and in an interhemispheric fashion in the presence of normal or small-sized lateral ventricles. Our choice patient positions are the neutral supine for the transfrontal approach and the lateral side of access down with the head slightly tilted up for the interhemispheric approach (Fig. 24-5).

At the conclusion of the surgery, the placement of a ventricular catheter through the opening to the lateral ventricle is recommended in cases of symptomatic hydrocephalus preoperatively, an unusually bloody dissection, and the presence of residual tumor that may not relieve pre-existing hydrocephalus. We have found, however, that the need for CSF diversion usually becomes clinically apparent in a delayed fashion, when symptoms appear days to even several weeks postoperatively. The obvious exception to this is acute new-onset obstructive hydrocephalus that results from an immediate postoperative third ventricular hemorrhage. As a result, in our practice, the intraoperative placement of a ventricular catheter in this setting is infrequent.

Cyst Aspiration

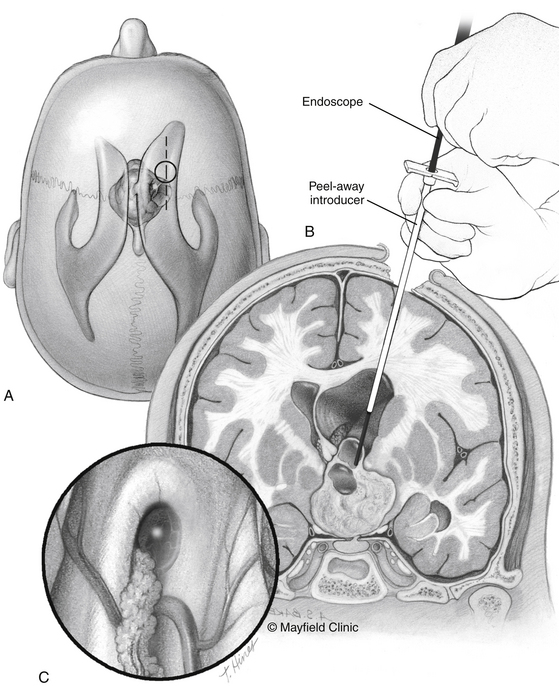

The placement of a catheter can be accomplished with stereotactic guidance or in an endoscope-assisted manner. Frameless stereotactic guidance is often accurate enough for safe catheterization of a large symptomatic cystic lesion and is recommended both in the case of simple aspiration, the placement of an Ommaya reservoir, or endoscope-assisted cyst fenestration (Fig. 24-6). In cases of hydrocephalus, an endoscope can safely navigate through the foramen of Monro, then allow for fenestration of a third ventricular cyst, and guide placement of a catheter within the deflated cyst under direct vision. However, it is a rare case of a craniopharyngioma that endoscopy can achieve more than fenestration and aspiration. Because most cyst walls have a close adherence of the third ventricle, endoscopic gross total resection is almost never possible.

Radiation Therapy

Intracavitary Therapy

Intracavitary delivery of radiation therapy refers to the instillation of a radioisotope (90 yttrium, 32 phosphorus, or 186 rhenium) into a deflated tumor cyst cavity through an indwelling catheter.21,22 By this method, a high dose (about 150 Gy) can be delivered to the surrounding secretory epithelial layer that lines the cyst with good tumor control. In the literature, results with respect to vision and endocrine function vary widely, and are part of the reason that this technique has not been widely accepted.

Outcomes

The primary treatment of craniopharyngiomas remains surgical. The literature indicates rates of gross total resection range widely between 10% to 90%. Yet compilation of all surgical studies reviewed reveals a rough average of 58%—a number that is optimistic in our experience.12,13,23–42 Estimates of gross total resection clearly depend on the postoperative imaging modality used; older studies in which CT was used reported lower rates of observed residuals.

Plenty of published evidence suggests that surgical resection is inadequate as the sole treatment for most craniopharyngiomas. Although it comes as no surprise that the rates of local tumor control after subtotal resection are generally low, rates after gross total resection are similar ranging between 6% and 57%.25,29–31,34,38,39,43

Operative morbidity includes postoperative visual dysfunction in 5.8% to 19% of patients and postoperative endocrinologic dysfunction in 50% to 100% of patients. Unlike most other brain tumors, an important consideration in the surgical treatment of craniopharyngiomas is perioperative mortality, which ranges between 1.1% to 10% in the early postoperative phase even in the most recent studies.12,23–26,28–32,34,35,38,40,42–45 These rates undoubtedly are associated with the anatomic location of these lesions, and their infiltrative relationship with the hypothalamus and vascular structures. Evidence also exists on the association of improved perioperative outcomes with decreased degrees of surgical resection.46–51

Trans-sphenoidal approaches and their variants with extension to the parasellar region using either the microscope or endoscope are effective in the treatment of primarily cystic craniopharyngiomas.11,20,52–67 Transventricular endoscopic approaches have a limited utility, primarily for fenestration of cystic lesions, followed by implantation of intracystic catheters under direct visualization.68–71 Several other surgical approaches have been described but have limited clinical applicability and no proven significant benefit in operative outcomes.72–75 A promising exception to this is the supraorbital craniotomy that has an increasing role, replacing the larger subfrontal and pterional approaches in less invasive and smaller tumors.76 Examples of these tumors and recommended approaches are shown in Fig. 24-7 and an overall recommended management of these lesions is shown in Fig. 24-8.

FIGURE 24-8 Diagram of recommended surgical management of craniopharyngiomas as per the authors’ experience.

The largest body of literature with respect to the radiation treatment of craniopharyngiomas deals with fractionated radiation therapy.35,51,77–91 The majority of the studies include patients treated in the adjuvant setting either postoperatively or at recurrence. Local control ranged between 80% to 100% and follow-up was up to 12 years post-treatment. Morbidity is limited; no visual dysfunction in general is observed when doses less than 60 Gy are used. When compared with patients after gross total resection alone, patients after subtotal resection that was followed by adjuvant fXRT, particularly during the early postoperative period, demonstrated improved tumor control rates and decreased morbidity.31,44,86,92–97

During the past decade, a number of publications on the treatment of craniopharyngiomas with stereotactic radiosurgery have reported that control rates range between 80% to 90% at 5 years post-treatment; response rates of 58% to 80% have been reported with median marginal dose of 9 to 16 Gy.98–109 Morbidity of this approach appears to be low with visual dysfunction in 6.1% of patients.100

Given the cystic nature of many craniopharyngiomas, stereotactic aspiration of the cystic component with the instillation of radioactive material can be an effective minimally invasive route of treatment. Several types of beta-emitting isotopes have been used, including phosphorus 32, ytrium 90, and rhenium 186.110–120 These colloid preparations can deliver high radiation doses of 100 to 200 Gy in the few surrounding millimeters, effectively treating the wall of cystic lesions, while depositing little radiation in the surrounding normal brain. Used as primary treatment after cyst aspiration or at recurrence, intracavitary radiation therapy has shown local tumor control rates of 70% to 96%.111,112,115

Stereotactic instillation of bleomycin has also shown 57% to 100% response rates.121–126 Although peritumoral edema can be observed postprocedure, it is rarely clinically limiting.121,122

Albright A.L., Hadjipanayis C.G., Lunsford L.D., et al. Individualized treatment of pediatric craniopharyngiomas. Childs Nerv Syst. 21, 2005. 8–9:649-654

Caldarelli M., Massimi L., Tamburrini G., et al. Long-term results of the surgical treatment of craniopharyngioma: the experience at the Policlinico Gemelli, Catholic University, Rome. Childs Nerv Syst. 21, 2005. 8–9:747-757

Cavallo L.M., Prevedello D.M., Solari D., et al. Extended endoscopic endonasal transsphenoidal approach for residual or recurrent craniopharyngiomas. J Neurosurg. 2009;111(3):578-589.

Chakrabarti I., Amar A.P., Couldwell W., et al. Long-term neurological, visual, and endocrine outcomes following transnasal resection of craniopharyngioma. J Neurosurg. 2005;102(4):650-657.

Combs S.E., Thilmann C., Huber P.E., et al. Achievement of long-term local control in patients with craniopharyngiomas using high precision stereotactic radiotherapy. Cancer. 2007;109(11):2308-2314.

Derrey S., Blond S., Reyns N., et al. Management of cystic craniopharyngiomas with stereotactic endocavitary irradiation using colloidal 186Re: a retrospective study of 48 consecutive patients. Neurosurgery. 2008;63(6):1045-1053.

Dhellemmes P., Vinchon M. Radical resection for craniopharyngiomas in children: surgical technique and clinical results. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2006;19(suppl 1):329-335.

Di Rocco C., Caldarelli M., Tamburrini G., et al. Surgical management of craniopharyngiomas—experience with a pediatric series. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2006;19(suppl 1):355-366.

Fitzek M.M., Linggood R.M., Adams J., et al. Combined proton and photon irradiation for craniopharyngioma: long-term results of the early cohort of patients treated at Harvard Cyclotron Laboratory and Massachusetts General Hospital. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;64(5):1348-1354.

Gardner P.A., Kassam A.B., Snyderman C.H., et al. Outcomes following endoscopic, expanded endonasal resection of suprasellar craniopharyngiomas: a case series. J Neurosurg. 2008;109(1):6-16.

Gardner P.A., Prevedello D.M., Kassam A.B., et al. The evolution of the endonasal approach for craniopharyngiomas. J Neurosurg. 2008;108(5):1043-1047.

Gonc E.N., Yordam N., Ozon A., et al. Endocrinological outcome of different treatment options in children with craniopharyngioma: a retrospective analysis of 66 cases. Pediatr Neurosurg. 2004;40(3):112-119.

Hukin J., Steinbok P., Lafay-Cousin L., et al. Intracystic bleomycin therapy for craniopharyngioma in children: the Canadian experience. Cancer. 2007;109(10):2124-2131.

Kassam A.B., Gardner P.A., Snyderman C.H., et al. Expanded endonasal approach, a fully endoscopic transnasal approach for the resection of midline suprasellar craniopharyngiomas: a new classification based on the infundibulum. J Neurosurg. 2008;108(4):715-728.

Kim S.D., Park J.Y., Park J., et al. Radiological findings following postsurgical intratumoral bleomycin injection for cystic craniopharyngioma. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2007;109(3):236-241.

Kobayashi T., Kida Y., Mori Y., et al. Long-term results of gamma knife surgery for the treatment of craniopharyngioma in 98 consecutive cases. J Neurosurg. 2005;103(suppl 6):482-488.

Lena G., Paz Paredes A., Scavarda D., et al. Craniopharyngioma in children: Marseille experience. Childs Nerv Syst. 2005;21:8-9. 778-784

Lin L.L., El Naqa I., Leonard J.R., et al. Long-term outcome in children treated for craniopharyngioma with and without radiotherapy. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2008;1(2):126-130.

Maira G., Anile C., Albanese A., et al. The role of transsphenoidal surgery in the treatment of craniopharyngiomas. J Neurosurg. 2004;100(3):445-451.

Minniti G., Saran F., Traish D., et al. Fractionated stereotactic conformal radiotherapy following conservative surgery in the control of craniopharyngiomas. Radiother Oncol. 2007;82(1):90-95.

Mottolese C., Szathmari A., Berlier P., et al. Craniopharyngiomas: our experience in Lyon. Childs Nerv Syst. 2005;21:8-9. 790-798

Samii M., Samii A. Surgical management of craniopharyngiomas. In: Schmidek H., Roberts D. Operative Neurosurgical Techniques. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2006:437-452.

Sosa I.J., Krieger M.D., McComb J.G. Craniopharyngiomas of childhood: the CHLA experience. Childs Nerv Syst. 2005;21:8-9. 785-789

Takahashi H., Yamaguchi F., Teramoto A. Long-term outcome and reconsideration of intracystic chemotherapy with bleomycin for craniopharyngioma in children. Childs Nerv Syst. 2005;21:8-9. 701-704

1. Moore K., Couldwell W. Craniopharyngioma. In: Bernstein M., Berger M. Neuro-oncology: The Essentials. New York: Thieme, 2000.

2. Kernohan J. Tumors of Congenital Origin. In: Mickler J., editor. Pathology of Central Nervous System. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1971:1927-1937.

3. Bunin G.R., Surawicz T.S., Witman P.A., et al. The descriptive epidemiology of craniopharyngioma. J Neurosurg. 1998;89:4547-4551.

4. Samii M., Tatagiba M. Surgical management of craniopharyngiomas: a review. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 1997;37:2141-2149.

5. Petruiset B. Craniopharyngiomas. In: Vinken P., Bruyn G. Handbook of Clinical Neurology. Amsterdam: North Holland, 1975.

6. Hoffman H., Long D.M., editor. Current Therapy in Neurological Surgery. Philadelphia: BC Becker, 1989.

7. Steno J. Microsurgical topography of craniopharyngiomas. Acta Neurochir Suppl (Wien). 1985;35:94-100.

8. Konovalov A.N. Microsurgery of tumours of diencephalic region. Neurosurg Rev. 1983;6:237-241.

9. Samii M., Samii A. Surgical management of craniopharyngiomas. In: Schmidek H., Roberts D. Operative Neurosurgical Techniques. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2006:437-452.

10. Rougerie J., Raimondi A. Craniopharyngiomas. In: Amador L., editor. Brain Tumors in Young. Springfield, IL: Charles C Thomas; 1983:599-618.

11. Kassam A.B., Gardner P.A., Snyderman C.H., et al. Expanded endonasal approach, a fully endoscopic transnasal approach for the resection of midline suprasellar craniopharyngiomas: a new classification based on the infundibulum. J Neurosurg. 2008;108(4):715-728.

12. Chakrabarti I., Amar A.P., Couldwell W., et al. Long-term neurological, visual, and endocrine outcomes following transnasal resection of craniopharyngioma. J Neurosurg. 2005;102(4):650-657.

13. Bin-Abbas B., Mawlawi H., Sakati N., et al. Endocrine sequelae of childhood craniopharyngioma. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2001;14(7):869-874.

14. DeVile C.J., Grant D.B., Hayward R.D., et al. Growth and endocrine sequelae of craniopharyngioma. Arch Dis Child. 1996;75(2):108-114.

15. Thomsett M.J., Conte F.A., Kaplan S.L., et al. Endocrine and neurologic outcome in childhood craniopharyngioma: review of effect of treatment in 42 patients. J Pediatr. 1980;97(5):728-735.

16. Matarazzo P., Genitori L., Lala R., et al. Endocrine function and water metabolism in children and adolescents with surgically treated intra/parasellar tumors. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2004;17(11):1487-1495.

17. Lyen K.R., Grant D.B. Endocrine function, morbidity, and mortality after surgery for craniopharyngioma. Arch Dis Child. 1982;57(11):837-841.

18. Kang J.K., Song J.U. Results of the management of craniopharyngioma in children. An endocrinological approach to the treatment. Childs Nerv Syst. 1988;4(3):135-138.

19. Gonc E.N., Yordam N., Ozon A., et al. Endocrinological outcome of different treatment options in children with craniopharyngioma: a retrospective analysis of 66 cases. Pediatr Neurosurg. 2004;40(3):112-119.

20. Shah R.N., Surowitz J.B., Patel M.R., et al. Endoscopic pedicled nasoseptal flap reconstruction for pediatric skull base defects. Laryngoscope. 2009;119(6):1067-1075.

21. Caceres A. Intracavitary therapeutic options in the management of cystic craniopharyngioma. Childs Nerv Syst. 2005;21:8-9. 705-718

22. Blackburn T.P., Doughty D., Plowman P.N. Stereotactic intracavitary therapy of recurrent cystic craniopharyngioma by instillation of 90yttrium. Br J Neurosurg. 1999;13(4):359-365.

23. Mottolese C., Szathmari A., Berlier P., et al. Craniopharyngiomas: our experience in Lyon. Childs Nerv Syst. 2005;21:8-9. 790-798

24. Duff J., Meyer F.B., Ilstrup D.M., et al. Long-term outcomes for surgically resected craniopharyngiomas. Neurosurgery. 2000;46(2):291-302. discussion 302-305

25. Albright A.L., Hadjipanayis C.G., Lunsford L.D., et al. Individualized treatment of pediatric craniopharyngiomas. Childs Nerv Syst. 2005;21:8-9. 649-654

26. Baskin D.S., Wilson C.B. Surgical management of craniopharyngiomas. A review of 74 cases. J Neurosurg. 1986;65(1):22-27.

27. Caldarelli M., di Rocco C., Papacci F., et al. Management of recurrent craniopharyngioma. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1998;140(5):447-454.

28. Caldarelli M., Massimi L., Tamburrini G., et al. Long-term results of the surgical treatment of craniopharyngioma: the experience at the Policlinico Gemelli, Catholic University, Rome. Childs Nerv Syst. 21, 2005. 8–9:747-757

29. Di Rocco C., Caldarelli M., Tamburrini G., et al. Surgical management of craniopharyngiomas—experience with a pediatric series. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2006;19(suppl 1):355-366.

30. Fahlbusch R., Honegger J., Paulus W., et al. Surgical treatment of craniopharyngiomas: experience with 168 patients. J Neurosurg. 1999;90(2):237-250.

31. Fischer E.G., Welch K., Shillito J.Jr, et al. Craniopharyngiomas in children. Long-term effects of conservative surgical procedures combined with radiation therapy. J Neurosurg. 1990;73(4):534-540.

32. Fisher P.G., Jenab J., Gopldthwaite P.T., et al. Outcomes and failure patterns in childhood craniopharyngiomas. Childs Nerv Syst. 1998;14(10):558-563.

33. Hoffman H.J. Craniopharyngiomas. Can J Neurol Sci. 1985;12(4):348-352.

34. Hoffman H.J., De Silva M., Humphreys R.P., et al. Aggressive surgical management of craniopharyngiomas in children. J Neurosurg. 1992;76(1):47-52.

35. Hoogenhout J., Otten B.J., Kazem I., et al. Surgery and radiation therapy in the management of craniopharyngiomas. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1984;10(12):2293-2297.

36. Khafaga Y., Jenkin D., Kanaan I., et al. Craniopharyngioma in children. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1998;42(3):601-606.

37. Kim S.K., Wang K.C., Shin S.H., et al. Radical excision of pediatric craniopharyngioma: recurrence pattern and prognostic factors. Childs Nerv Syst. 2001;17(9):531-536. discussion 537

38. Lena G., Paz Paredes A., Scavarda D., et al. Craniopharyngioma in children: Marseille experience. Childs Nerv Syst. 2005;21:8-9. 778-784

39. Lin L.L., El Naqa I., Leonard J.R., et al. Long-term outcome in children treated for craniopharyngioma with and without radiotherapy. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2008;1(2):126-130.

40. Mark R.J., Lutge W.R., Shimizu K.T., et al. Craniopharyngioma: treatment in the CT and MR imaging era. Radiology. 1995;197(1):195-198.

41. Sosa I.J., Krieger M.D., McComb J.G. Craniopharyngiomas of childhood: the CHLA experience. Childs Nerv Syst. 2005;21:8-9. 785-789

42. Van Effenterre R., Boch A.L. Craniopharyngioma in adults and children: a study of 122 surgical cases. J Neurosurg. 2002;97(1):3-11.

43. Dhellemmes P., Vinchon M. Radical resection for craniopharyngiomas in children: surgical technique and clinical results. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2006;19(suppl 1):329-335.

44. Kalapurakal J.A., Goldman S., Hsieh Y.C., et al. Clinical outcome in children with craniopharyngioma treated with primary surgery and radiotherapy deferred until relapse. Med Pediatr Oncol. 2003;40(4):214-218.

45. Symon L., Pell M.F., Habib A.H. Radical excision of craniopharyngioma by the temporal route: a review of 50 patients. Br J Neurosurg. 1991;5(6):539-549.

46. Colangelo M., Ambrosio A., Ambrosio C. Neurological and behavioral sequelae following different approaches to craniopharyngioma. Long-term follow-up review and therapeutic guidelines. Childs Nerv Syst. 1990;6(7):379-382.

47. Fraioli M.F., Santoni R., Fraioli C., et al. “Conservative” surgical approach and early postoperative radiotherapy in a patient with a huge cystic craniopharyngioma. Childs Nerv Syst. 2006;22(2):151-163.

48. Ivkov M., Ribarić I., Slavik E., et al. Surgical treatment of craniopharyngiomas in adults. Acta Neurochir Suppl (Wien). 1979;28(2):352-356.

49. Merchant T.E., Kiehna E.N., Sanford R.A., et al. Craniopharyngioma: the St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital experience 1984-2001. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2002;53(3):533-542.

50. Honegger J., Buchfelder M., Fahlbusch R. Surgical treatment of craniopharyngiomas: endocrinological results. J Neurosurg. 1999;90(2):251-257.

51. Lichter A.S., Wara W.M., Sheline G.E., et al. The treatment of craniopharyngiomas. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1977;2:7-8. 675-683

52. Rudnick E.F., DiNardo L.J. Image-guided endoscopic endonasal resection of a recurrent craniopharyngioma. Am J Otolaryngol. 2006;27(4):266-267.

53. Im S.H., Wang K.C., Kim S.K., et al. Transsphenoidal microsurgery for pediatric craniopharyngioma: special considerations regarding indications and method. Pediatr Neurosurg. 2003;39(2):97-103.

54. Konig A., Ludecke D.K., Herrmann H.D. Transnasal surgery in the treatment of craniopharyngiomas. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1986;83:1-2. 1-7

55. Couldwell W.T., Weiss M.H., Rabb C., et al. Variations on the standard transsphenoidal approach to the sellar region, with emphasis on the extended approaches and parasellar approaches: surgical experience in 105 cases. Neurosurgery. 2004;55(3):539-550.

56. Abe T., Ludecke D.K. Transnasal surgery for infradiaphragmatic craniopharyngiomas in pediatric patients. Neurosurgery. 1999;44(5):957-966.

57. Frank G., Pasquini E., Doglietto F., et al. The endoscopic extended transsphenoidal approach for craniopharyngiomas. Neurosurgery. 59(1 suppl 1), 2006. oNS75–83

58. Norris J.S., Pavaresh M., Afshar F. Primary transsphenoidal microsurgery in the treatment of craniopharyngiomas. Br J Neurosurg. 1998;12(4):305-312.

59. Laws E.R. Jr: Transsphenoidal removal of craniopharyngioma. Pediatr Neurosurg. 1994;21(suppl 1):57-63.

60. Laws E.R.Jr, Morris A.M., Maartens N. Gliadel for pituitary adenomas and craniopharyngiomas. Neurosurgery. 2003;53(2):255-269.

61. Locatelli D., Levi D., Rampa F., et al. Endoscopic approach for the treatment of relapses in cystic craniopharyngiomas. Childs Nerv Syst. 2004;20:11-12. 863-867

62. Maira G., Anile C., Albanese A., et al. The role of transsphenoidal surgery in the treatment of craniopharyngiomas. J Neurosurg. 2004;100(3):445-451.

63. Cavallo L.M., Prevedello D.M., Solari D., et al. Extended endoscopic endonasal transsphenoidal approach for residual or recurrent craniopharyngiomas. J Neurosurg. 2009;111(3):578-589.

64. Gardner P.A., Kassam A.B., Snyderman C.H., et al. Outcomes following endoscopic, expanded endonasal resection of suprasellar craniopharyngiomas: a case series. J Neurosurg. 2008;109(1):6-16.

65. Gardner P.A., Prevedello D.M., Kassam A.B., et al. The evolution of the endonasal approach for craniopharyngiomas. J Neurosurg. 2008;108(5):1043-1047.

66. Kassam A.B., Prevedello D.M., Thomas A., et al. Endoscopic endonasal pituitary transposition for a transdorsum sellae approach to the interpeduncular cistern. Neurosurgery. 2008;62(3 suppl 1):57-72. discussion 72-74

67. Lunsford L.D., Niranjan A., Martin J.J., et al. Radiosurgery for miscellaneous skull base tumors. Prog Neurol Surg. 2007;20:192-205.

68. Joki T., Oi S., Babapour B., et al. Neuroendoscopic placement of Ommaya reservoir into a cystic craniopharyngioma. Childs Nerv Syst. 2002;18(11):629-633.

69. Delitala A., Brunori A., Chiappetta F. Purely neuroendoscopic transventricular management of cystic craniopharyngiomas. Childs Nerv Syst. 2004;20:11-12. 858-862

70. Cinalli G., Spennato P., Cianciulli E., et al. The role of transventricular neuroendoscopy in the management of craniopharyngiomas: three patient reports and review of the literature. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2006;19(suppl 1):341-354.

71. Pettorini B.L., Tamburrini G., Massimi L., et al. Endoscopic transventricular positioning of intracystic catheter for treatment of craniopharyngioma. Technical note. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2009;4(3):245-248.

72. Siomin V., Spektor S., Beni-Adani L., et al. Application of the orbito-cranial approach in pediatric neurosurgery. Childs Nerv Syst. 2001;17(10):612-617.

73. Shirane R., Hayashi T., Tominaga T. Fronto-basal interhemispheric approach for craniopharyngiomas extending outside the suprasellar cistern. Childs Nerv Syst. 2005;21:8-9. 669-678

74. Inoue H.K., Fujimaki H., Kohga H., et al. Basal interhemispheric supra- and/or infrachiasmal approaches via superomedial orbitotomy for hypothalamic lesions: preservation of hypothalamo-pituitary functions in combination treatment with radiosurgery. Childs Nerv Syst. 1997;13(5):250-256.

75. Al-Mefty O., Ayoubi S., Kadri P.A. The petrosal approach for the total removal of giant retrochiasmatic craniopharyngiomas in children. J Neurosurg. 2007;106(suppl 2):87-92.

76. Kabil M.S. Shahinian HK: application of the supraorbital endoscopic approach to tumors of the anterior cranial base. J Craniofac Surg. 2005;16(6):1070-1074. discussion 1075

77. Varlotto J.M., Flickinger J.C., Kondziolka D., et al. External beam irradiation of craniopharyngiomas: long-term analysis of tumor control and morbidity. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2002;54(2):492-499.

78. Wara W.M., Sneed P.K., Larson D.A. The role of radiation therapy in the treatment of craniopharyngioma. Pediatr Neurosurg. 1994;21(suppl 1):98-100.

79. Calvo F.A., Hornedo J., Arellano A., et al. Radiation therapy in craniopharyngiomas. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1983;9(4):493-496.

80. Combs S.E., Thilmann C., Huber P.E., et al. Achievement of long-term local control in patients with craniopharyngiomas using high precision stereotactic radiotherapy. Cancer. 2007;109(11):2308-2314.

81. Fitzek M.M., Linggood R.M., Adams J., et al. Combined proton and photon irradiation for craniopharyngioma: long-term results of the early cohort of patients treated at Harvard Cyclotron Laboratory and Massachusetts General Hospital. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;64(5):1348-1354.

82. Flickinger J.C., Lunsford L.D., Singer J., et al. Megavoltage external beam irradiation of craniopharyngiomas: analysis of tumor control and morbidity. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1990;19(1):117-122.

83. Flickinger J.C., Deutsch M., Lunsford L.D. Repeat megavoltage irradiation of pituitary and suprasellar tumors. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1989;17(1):171-175.

84. Gurkaynak M., Ozyar E., Zorlu F., et al. Results of radiotherapy in craniopharyngiomas analysed by the linear quadratic model. Acta Oncol. 1994;33(8):941-943.

85. Minniti G., Saran F., Traish D., et al. Fractionated stereotactic conformal radiotherapy following conservative surgery in the control of craniopharyngiomas. Radiother Oncol. 2007;82(1):90-95.

86. Moon S.H., Kim I.H., Park S.W., et al. Early adjuvant radiotherapy toward long-term survival and better quality of life for craniopharyngiomas—a study in single institute. Childs Nerv Syst. 2005;21:8-9. 799-807

87. Onoyama Y., Ono K., Yabumoto E., et al. Radiation therapy of craniopharyngioma. Radiology. 1977;125(3):799-803.

88. Pemberton L.S., Dougal M., Magee B., et al. Experience of external beam radiotherapy given adjuvantly or at relapse following surgery for craniopharyngioma. Radiother Oncol. 2005;77(1):99-104.

89. Richmond I.L., Wara W.M., Wilson C.B. Role of radiation therapy in the management of craniopharyngiomas in children. Neurosurgery. 1980;6(5):513-517.

90. Schulz-Ertner D., Frank C., Herfarth K.K., et al. Fractionated stereotactic radiotherapy for craniopharyngiomas. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2002;54(4):1114-1120.

91. Thompson I.L., Griffin T.W., Parker R.G., et al. Craniopharyngioma: the role of radiation therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1978;4:11-12. 1059-1063

92. Cavazzuti V., Fischer E.G., Welch K., et al. Neurological and psychophysiological sequelae following different treatments of craniopharyngioma in children. J Neurosurg. 1983;59(3):409-417.

93. Danoff B.F., Cowchock F.S., Kramer S. Childhood craniopharyngioma: survival, local control, endocrine and neurologic function following radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1983;9(2):171-175.

94. Wen B.C., Hussey D.H., Staples J., et al. A comparison of the roles of surgery and radiation therapy in the management of craniopharyngiomas. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1989;16(1):17-24.

95. Stripp D.C., Maity A., Janss A.J., et al. Surgery with or without radiation therapy in the management of craniopharyngiomas in children and young adults. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2004;58(3):714-720.

96. Weiss M., Sutton L., Marcial V., et al. The role of radiation therapy in the management of childhood craniopharyngioma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1989;17(6):1313-1321.

97. Rajan B., Ashley S., Gorman C., et al. Craniopharyngioma—a long-term result following limited surgery and radiotherapy. Radiother Oncol. 1993;26(1):1-10.

98. Amendola B.E., Wolf A., Coy S.R., et al. Role of radiosurgery in craniopharyngiomas: a preliminary report. Med Pediatr Oncol. 2003;41(2):123-127.

99. Chiou S.M., Lunsford L.D., Niranjan A., et al. Stereotactic radiosurgery of residual or recurrent craniopharyngioma, after surgery, with or without radiation therapy. Neuro Oncol. 2001;3(3):159-166.

100. Kobayashi T., Kida Y., Mori Y., et al. Long-term results of gamma knife surgery for the treatment of craniopharyngioma in 98 consecutive cases. J Neurosurg. 2005;103(suppl 6):482-488.

101. Kobayashi T., Tanaka T., Kida Y. Stereotactic gamma radiosurgery of craniopharyngiomas. Pediatr Neurosurg. 1994;21(suppl 1):69-74.

102. Pollock B.E., Natt N., Schomberg P.J. Stereotactic management of craniopharyngiomas. Stereotact Funct Neurosurg. 2002;79(1):25-32.

103. Ulfarsson E., Lindquist C., Roberts M., et al. Gamma knife radiosurgery for craniopharyngiomas: long-term results in the first Swedish patients. J Neurosurg. 2002;97(suppl 5):613-622.

104. Kondziolka D., Nathoo N., Flickinger J.C., et al. Long-term results after radiosurgery for benign intracranial tumors. Neurosurgery. 2003;53(4):815-822.

105. Kim M.S., Lee S.I., Sim S.H. Brain tumors with cysts treated with gamma knife radiosurgery: is microsurgery indicated? Stereotact Funct Neurosurg. 1999;72(suppl 1):38-44.

106. Jackson A.S., St George E.J., Hayward R.J., et al. Stereotactic radiosurgery. XVII: recurrent intrasellar craniopharyngioma. Br J Neurosurg. 2003;17:2138-2143.

107. Mokry M. Craniopharyngiomas: a six year experience with gamma knife radiosurgery. Stereotact Funct Neurosurg. 1999;72(suppl 1):140-149.

108. Plowman P.N., Wraith C., Royle N., et al. Stereotactic radiosurgery. IX. Craniopharyngioma: durable complete imaging responses and indications for treatment. Br J Neurosurg. 1999;13(4):352-358.

109. Adler J.R.Jr, Gibbs I.C., Puataweepong P., et al. Visual field preservation after multisession cyberknife radiosurgery for perioptic lesions. Neurosurgery. 2006;59(2):244-254.

110. Julow J., Backlund E.O., Lányi F., et al. Long-term results and late complications after intracavitary yttrium-90 colloid irradiation of recurrent cystic craniopharyngiomas. Neurosurgery. 2007;61(2):288-295. discussion 295-296

111. Derrey S., Blond S., Reyns N., et al. Management of cystic craniopharyngiomas with stereotactic endocavitary irradiation using colloidal 186Re: a retrospective study of 48 consecutive patients. Neurosurgery. 2008;63(6):1045-1053.

112. Hasegawa T., Kondziolka D., Hadjipanayis C.G., et al. Management of cystic craniopharyngiomas with phosphorus-32 intracavitary irradiation. Neurosurgery. 2004;54(4):813-822.

113. Hechtman C.D., Li Z., Mansur D.B., et al. Dose distribution outside of a sphere of P-32 chromic phosphorous colloid. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2005;63(3):961-968.

114. Lange M., Kirsch C.M., Steude U., et al. Intracavitary treatment of intrasellar cystic craniopharyngeomas with 90-Yttrium by trans-sphenoidal approach—a technical note. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1995;135:3-4. 206-209

115. Lunsford L.D., Pollock B.E., Kondziolka D.S., et al. Stereotactic options in the management of craniopharyngioma. Pediatr Neurosurg. 1994;21(suppl 1):90-97.

116. Pollock B.E., Lunsford L.D., Kondziolka D., et al. Phosphorus-32 intracavitary irradiation of cystic craniopharyngiomas: current technique and long-term results. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1995;33(2):437-446.

117. Schefter J.K., Allen G., Cmelak A.J., et al. The utility of external beam radiation and intracystic 32P radiation in the treatment of craniopharyngiomas. J Neurooncol. 2002;56(1):69-78.

118. Van den Berge J.H., Blaauw G., Breeman W.A., et al. Intracavitary brachytherapy of cystic craniopharyngiomas. J Neurosurg. 1992;77(4):545-550.

119. Voges J., Sturm V., Lehrke R., et al. Cystic craniopharyngioma: long-term results after intracavitary irradiation with stereotactically applied colloidal beta-emitting radioactive sources. Neurosurgery. 1997;40(2):263-269. discussion 269-270

120. Pan D.H., Lee L.S., Huang C.I., et al. Stereotactic internal irradiation for cystic craniopharyngiomas: a 6-year experience. Stereotact Funct Neurosurg. 1990;54-55:525-530.

121. Hukin J., Steinbok P., Lafay-Cousin L., et al. Intracystic bleomycin therapy for craniopharyngioma in children: the Canadian experience. Cancer. 2007;109(10):2124-2131.

122. Hader W.J., Steinbok P., Hukin J., et al. Intratumoral therapy with bleomycin for cystic craniopharyngiomas in children. Pediatr Neurosurg. 2000;33(4):211-218.

123. Mottolese C., Stan H., Hermier M., et al. Intracystic chemotherapy with bleomycin in the treatment of craniopharyngiomas. Childs Nerv Syst. 2001;17(12):724-730.

124. Kim S.D., Park J.Y., Park J., et al. Radiological findings following postsurgical intratumoral bleomycin injection for cystic craniopharyngioma. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2007;109(3):236-241.

125. Park D.H., Park J.Y., Kim J.H., et al. Outcome of postoperative intratumoral bleomycin injection for cystic craniopharyngioma. J Korean Med Sci. 2002;17(2):254-259.

126. Takahashi H., Yamaguchi F., Teramoto A. Long-term outcome and reconsideration of intracystic chemotherapy with bleomycin for craniopharyngioma in children. Childs Nerv Syst. 2005;21:8-9. 701-704