Cranial Nerves

General

BACKGROUND

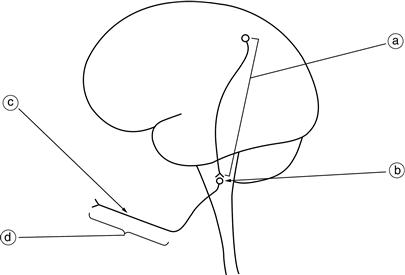

Abnormalities found when examining the ‘cranial nerves’ may arise from lesions at different levels (Fig. 5.1) including:

When examining the cranial nerves, you need to establish whether there is an abnormality in cranial nerve function, the nature and extent of the abnormality and any associations.

More than one cranial nerve may be abnormal:

• when affected by a generalised disorder (e.g. myasthenia gravis)

• following multiple lesions (e.g. multiple sclerosis, cerebrovascular disease, basal meningitis).

Abnormalities of cranial nerves are very useful in localising a lesion within the central nervous system.

Examination of the eye and its fields allows the examination of a tract running from the eye to the occipital lobe that also crosses the midline.

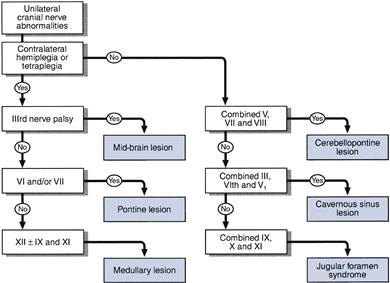

The nuclei of the cranial nerves within the brainstem act as markers for the level of the lesion (Fig. 5.2). Particularly useful are the nuclei of the III, IV, VI, VII and XII nerves. When the tongue and face are affected on the same side as a hemiplegia, the lesion must be above the XII and VII nucleus respectively. If a cranial nerve is affected on the opposite side to a hemiparesis, then the causative lesion must be at the level of the nucleus of that nerve. This is illustrated in Figure 5.3.

Multiple cranial nerve abnormalities are also recognised in a number of syndromes:

• Unilateral V, VII and VIII: cerebellopontine angle lesion.

• Unilateral III, IV, V1 and VI: cavernous sinus lesion.

• Combined unilateral IX, X and XI: jugular foramen syndrome.

– Combined bilateral X, XI and XII:

– if lower motor neurone = bulbar palsy

The most common cause of intrinsic brainstem lesions in younger patients is multiple sclerosis, and in older patients it is vascular disease. Rarer causes include gliomas, lymphomas and brainstem encephalitis.

TIP

TIP