Chapter 9 CPAP, APAP and BIPAP

1 INTRODUCTION

Positive airway pressure (PAP) therapy, including continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP), adjustable positive airway pressure (APAP), and bi-level positive airway pressure (BI-PAP), is an important, non-invasive treatment for sleep disordered breathing (SDB). PAP therapy as a treatment for obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) was first developed by Colin E. Sullivan and colleagues in 1980 at the University of Sydney, New South Wales, Australia. The effectiveness of CPAP treatment first received public attention in 1981 when Sullivan published his findings, documenting that low pressures of air delivered through the nasal passages had the ability to splint the airway and provide a night of unobstructed, uninterrupted sleep, while reducing daytime somnolence.1 The recommended and only treatment available for OSA before Sullivan’s discovery was the surgical procedure of tracheotomy. Therapy models for PAP treatment have been incorporated into medical practices utilizing a variety of techniques. While surgical procedures are invasive and have variable success for OSA, PAP therapy has proven to be an effective treatment that corrects the obstructed airway, reduces the severity of SDB symptoms and the occurrence of associated co-morbidities, and has no associated risks, although compliance although remains an issue. In any case it is the first-line treatment for OSA. This chapter provides a description of how PAP is administered and a review of its history and efficacies.

2 OBJECTIVES OF PAP THERAPY IN AN ENTPRACTICE

Surgeons are understandably interested in surgical therapies for treating OSA. However, to nurture patient referrals, ENT physicians need to incorporate PAP treatments into their practice. Medical colleagues do not always have the resources or interest to examine the upper respiratory tract, diagnose SDB, and recommend appropriate patients for surgical consultations. Unfortunately, the medical community is disenchanted with surgical therapies in treating SDB due to a glaring absence of EBM Level I prospective, controlled studies demonstrating the benefit of surgery.2 Level II studies are also missing. Furthermore, the sleep physician’s anecdotal experience with surgery is not excellent for they rarely see the successes, but all too often see the failures. It is therefore the authors’ opinion that if ENT physicians choose to participate in the evaluation and management of SDB, they must offer not only home sleep testing, but also PAP administration as part of their sleep services. Currently, surgeons enjoy patient and primary care physician referrals, but if we are to maintain a position in the sleep market and retain and nurture a steady flow of patients, we must provide comprehensive services. This includes sleep testing and PAP administration in addition to our history, physical examination and surgical procedures. Setting up and managing a poly-somnographic operation is time consuming and complex. It is also expensive for patients, insurance companies, and the greater healthcare system.

Shown by numerous validation studies, multi-channel home sleep testing has proven to be highly correlated with polysomnography and equally effective in diagnosing OSA.3–6 Home sleep testing is easy to perform and fairly reimbursed. PAP therapy is more difficult to perform and is poorly reimbursed. However, if the head and neck surgeon does not provide PAP services, they will not have a comprehensive SDB practice and will ultimately lose their position in the sleep market. There was a time when allergists wished to become the entry point for patients with sinusitis. The head and neck surgery community countered, and today, patients with chronic sinusitis come to our office for evaluation, medical and surgical therapies. The authors propose that the diagnosis and treatment of OSA must follow a similar path in establishing itself within the medical community.

3 THERAPEUTIC INDICATIONS

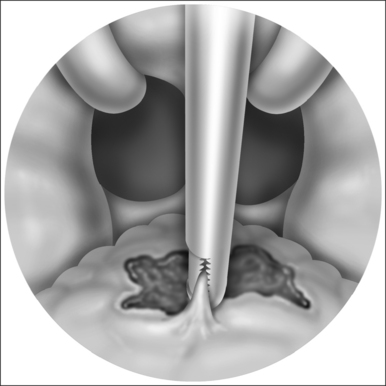

Surgical indications for the treatment of sleep disordered breathing are for the individuals who suffer from severe nasal obstruction, most notably nasal polyps, and the patients with four plus tonsils, Friedman Stage 1.7 Unfor-tunately, the majority of SDB is obstruction at the tongue base, an area where surgical therapy is not yet uniformly successful. Therefore, a large number of individuals with SDB must be provided PAP therapy, and only if this truly fails, be considered for surgical interventions. The senior author generally advises patients he will only discuss surgical therapies after the SDB patient has learned to use CPAP, and then makes an informed decision to pursue surgical options. Snoring, absent OSA, is still a surgical disease.

The indications for positive airway pressure therapy are individuals with significant SDB. The Center for Medicaid and Medicare Services (CMS) guidelines indicate PAP therapy for individuals with an Apnea Hypopnea Index (AHI) of 15 events per hour or greater or an AHI of five or greater with two or more co-morbidities.8 Co-morbidities are listed in Table 9.1. There are many individuals with an AHI of five but less than 15, who are diagnosed with mild OSA, for whom PAP therapy should be recommended. This group would include those who are symptomatic, most notably presenting with excessive daytime sleepiness, hypertension and cardiovascular co-morbidities, and those who are not surgical candidates. With the prevalence of obesity increasing, the number of those patients will increase over time.

| Category | Condition | References |

|---|---|---|

| Cardiac | Hypertension Congestive heart failure Ischemic heart disease Dysrhythmias |

35, 36 37–41 42–46 47–49 |

| Respiratory | Pulmonary hypertension | 50 |

| Neurologic | Stroke Headache |

51–53 54, 55 |

| Metabolic | Insulin resistance Metabolic syndrome |

56–58 59, 60 |

| Gastrointestinal | Gastroesophageal reflux disease | 61–64 |

| Genitourinary | Erectile dysfunction Nocturia, enuresis |

65, 66 67, 68 |

4 ENT PRACTICE MODEL

4.1 AUTO-TITRATING PAP

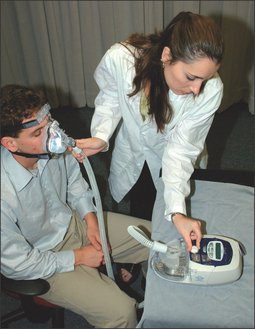

Those who utilize laboratory polysomnography will often initiate PAP therapy from their lab. This is done through a split night titration, where PAP therapy is administered half way through a polysomnography sleep test if the sleep technician believes the patient is positive for SDB. A median pressure is titrated and prescribed for a CPAP machine. Those who conduct multi-channel home sleep testing and provide all their services out of their office can do the same with auto-PAP home titrations. Introduced to the market in 2000, auto-PAP machines have the ability to automatically adjust pressure settings throughout a night’s sleep to ensure that the correct pressure is being emitted to splint open the airway.9 There are several models of auto-adjusting PAP machines available in today’s market, and these are used for the initial titration and trial. They can also be used for the PAP treatment. Two recent models are seen in Figures 9.1 and 9.2.

An auto-titrating PAP machine is provided to a SDB patient who typically takes it home and uses it for 3–7 days. They then return the machine to the prescribing physician. If the patient and/or their insurance choose to provide an APAP machine, the prescription is written for the mask and the machine. If the insurance company only covers fixed pressure CPAP, the prescription also includes the 95th percentile pressure for the CPAP machine. This is the pressure that will splint the airway open 95% of the time. Fixed pressure CPAP does well, just not quite as well as APAP. The pros and cons of APAP versus CPAP are an evolving controversy. Typically, a durable medical equipment (DME) provider supplies the equipment. While some patients report immediate compliance and benefit, some experience difficulties. These individuals need to be seen in the office, their equipment adjusted, and compliance nurtured.

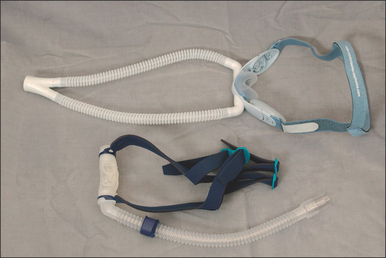

4.2 MASKS

Numerous masks are available, and many believe the mask is the key to PAP therapy. Nasal masks are generally easier to use, as they are less intrusive and certainly less claust-rophobic, but individuals who are nighttime mouth breathers will require full face masks. There is no single mask to satisfy everyone, therefore an assortment of nasal masks and full face masks should be maintained. Figures 9.3 and 9.4 show several masks currently on the market. Patients can look at and try these in the office, and select a preference for model and size. The mask is also trialed with the auto-PAP machine for 3–7 days.

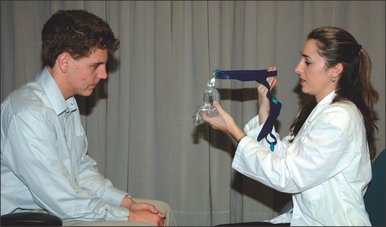

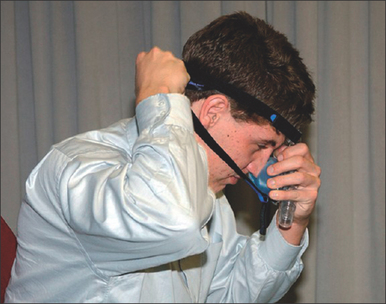

4.3 THE OFFICE VISIT

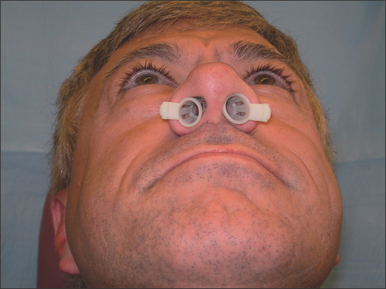

First and foremost, any lingering questions about the patient’s sleep study results should be addressed. The diagnosis and the importance of SDB as a health risk should be reiterated. Information in the form of pamphlets and handouts is an excellent supplement. To begin the PAP titration, the patient is asked if they are a mouth breather or a nasal breather to ensure that an appropriate trial mask is chosen. The titration/trial mask is then fitted to the patient and they are asked to practice putting it on their face, preferably in front of a mirror. Once the patient is comfortable handling the mask, it is connected to the titration PAP machine, and the starting procedure is demonstrated. The patient should spend a few minutes with the PAP machine on, to get an idea of how the pressure will feel. At the end of the appointment, logistical information about the PAP titration should be reviewed, and additional questions answered. This is a good time to hand out pamphlets and literature. A list of resourceful websites is generally helpful, as well as contact information, should difficulties arise. A patient should walk out of the PAP consultation with the confidence that the PAP treatment is important to their longevity and that this is a treatment they can do. Figures 9.5 to 9.10 demonstrate an office appointment for PAP fitting.

4.4 FOLLOW-UP AND COMPLIANCE TECHNIQUES

Many PAP therapy patients take one look at the mask and the machine and announce that they cannot use it. This does not constitute CPAP failure, and the physician and sleep technician must encourage patients to learn to use the PAP machine. Only once patients learn how to use PAP can they make an educated opinion about its long-term use. There are many tricks to nurture PAP use, and each practice needs to develop its own. During the 3–7 day trial, follow-up should be continuously maintained. The first night will be the most difficult for the majority of patients. A follow-up phone call should be made by the sleep technician to inquire about any difficulties the patient may have had with the PAP machine and the mask. At this time, suggestions can be made to nurture compliance. The first seemingly simple aid is to provide the patient with a sleeping pill for the first several nights. Lunesta®, while expensive and often not covered by insurance companies, is probably the preferred sleeping pill, for it is not addictive. Ambien® is an alternative. Tranquilizers and other medications are not ideal, as they will worsen the patient’s SDB, and if the patient does not use the PAP treatment, it will place them at risk for SDB difficulties, death included.

Some patients are claustrophobic and find the mask too frightening to wear. For these patients, a tranquilizer can be considered. Although time consuming, the best approach is probably to develop a program in which the patient slowly gets used to the mask and then the PAP machine. Our paradigm for the ‘difficult’ patient is to dispense the selected mask from the office and ask the patient to first wear it as an open mask without a hose and the PAP machine, just in the evenings and around their home. As they become used to this, then they can be asked to wear it during sleep. Once they are comfortable with the mask, the hose and PAP machine can be added. This can be started while awake and watching television and only after a few nights should they wear the PAP to bed. A second paradigm is to provide a PAP machine beginning at very low pressures, typically 4–6 cmH2O, increasing the pressure every couple of days until it reaches a therapeutic level. Another paradigm is to dispense an auto-adjusting PAP machine. Theoretically this only provides the required pressure to splint the sleeping airway, and is therefore unobtrusive. If the patient has difficulties, the maximum pressure can be turned down and then increased slowly. For those who experience drying, humidification can be added. In some cases, heated humidification is required. The humidifier seen in Figure 9.11 is typically an external attachment to the PAP machine. Humidification has its complexities, for the equipment and the tubing are prone to mold growth and therefore require a more aggressive daily cleaning program. The experienced PAP sleep technician and the DME can assist the patient in adopting a cleaning regime.

4.6 THE SURGEON’S ROLE IN PAP COMPLIANCE

While surgery is generally the preferred treatment for palatal snoring in an individual with an AHI of less than 15, without the co-morbidities of sleep disordered breathing, and without the two obvious surgical cures of nasal polyps and four plus tonsils, Friedman Stage I, PAP is considered the primary treatment for SDB. Compliance remains a challenging problem. Surgeons should encourage head and neck surgery evaluation of these patients and explore opportunities to improve CPAP compliance rather than surgical cure.

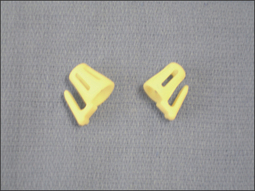

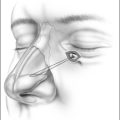

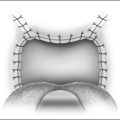

Chronic sinusitis is documented by a sinus CT scan and is treated with endoscopic sinus surgery. Much of the nasal obstruction occurs in the anterior valve area. For these individuals, sinus cones seen in Figures 9.12 and 9.13 have been found to be useful, particularly for nighttime breathing. For those who have valve problems, septoplasty, spreader grafts, alar battans, and myriad valve plasties may be considered.10 There is little science to document their benefit in nasal obstruction. There is no science to document their benefit in the treatment of PAP compliance.

Turbinectomy is a widely practiced operation. Limited turbinectomy has minor benefit and little risk. Aggressive turbinectomy has no evidence-based medicine Level I or Level II documented benefit. Aggressive turbinectomy may cause atrophic rhinitis.11 While many surgeons say it does not, there is an association, called the empty nose association, and a number of rhinological referral nasal practices that say the condition does occur. This is mentioned because those who perform aggressive turbinectomy owe the rest of the head and neck community the dignity of a well-controlled study, at least Level III evidence-based medicine, to show benefit. For the surgeon interested in the nasal surgery of the future, improved valvular surgery is needed. The senior author’s prediction is that someone will develop an alloplastic graft that will be placed submucosally, perhaps beneath the upper lateral cartilages, and will hold open the valve. Butterfly grafts also work, but are not aesthetically ideal. This is an area deserving clinical research.

4.7 PRESCRIPTIONS

It would be ideal to prescribe an auto-adjusting PAP machine to all patients. Unfortunately, fixed pressure CPAP machines are less expensive so insurance companies will only provide coverage for these. Both the physician and the DME are then challenged to nurture CPAP compliance, and adopt a follow-up procedure for their patients. A drawback to CPAP machines is that the fixed pressure may need adjustment to slightly higher or lower pressures to maintain a therapeutic level. This is where follow-up is most important, as patients may not always contact their healthcare provider when difficulties arise.

4.9 RARE CASES

Occasionally, there are individuals for whom CPAP is difficult. These individuals are typically those with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and those with very high pressures. Cheyne–Stokes breathing requires more complex positive airway pressure paradigms. Cheyne–Stokes breathing is typically seen in Class 3 and Class 4 heart failure and in patients with neurological problems.12 These rare cases are best referred to a sleep physician with a sleep laboratory for their evaluation and treatment.

5 THERAPEUTIC BENEFITS AND RISKS

5.1 BENEFITS

PAP therapy offers life-changing benefits for SDB sufferers. Depending on the dedication of the patient to adhere to therapy and frequency of use, results can be seen as early as 1 month. Excessive daytime somnolence can be reduced through long-term use. Depressive symptoms are often reduced and an increase in quality of life has been documented by numerous studies.13–16 Snoring is eradicated, as PAP keeps the patient’s airway open. Often seen in OSA patients, nocturia is also reduced with the use of PAP.17 Additionally motor vehicle accidents have been shown to decrease among treated OSA sufferers.18

Many SDB sufferers often present or are threatened with an increased risk of the aforementioned co-morbidities. Numerous studies have shown that PAP therapy significantly reduces blood pressure levels in systolic and diastolic hypertensive SDB patients, and offers a successful alternative to pharmacological treatments.19–22 PAP therapy is especially effective in patients with drug-resistant hypertension.23 Additionally, PAP therapy can benefit SDB patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus, by decreasing insulin sensitivity. Recent studies have shown that elevated glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c) levels in type 2 diabetics are reduced through long-term PAP therapy.24–27

Cholesterol levels and a decrease in the associated risk for cardiovascular disease have also shown promise from PAP therapy. Studies have shown that clinically significant reductions in cholesterol levels have been demonstrated by PAP therapy use, with results seen as early as 1 month.28,29 Additionally, poor cardiac indicators such as cardiac contractility, heart rate variability, and hemodynamics at rest can be improved within 1 week of PAP therapy.30

Changes in the structure of the upper airway anatomy have also been seen in long-term PAP users. Through continuous splinting of the upper airway, PAP therapy has the ability to permanently morph anatomy that was once causing obstruction. Through the use of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), studies have shown increase in pharyngeal volume and decrease in tongue volume and upper airway mucosal water in chronic nasal CPAP therapy use.31

5.2 RISKS

There are risks associated with PAP therapy, none of which is life threatening. Nasal symptoms are often seen with an increased risk of nasal congestion, rhinorrhea, and rare cases of pneumonia.32,33 These symptoms can be reversed through heated humidification, or nasal steroids. The mask may also elicit claustrophobia in patients.34 Mold growth in humidifiers that do not have a proper cleaning regime can also cause complex respiratory illnesses. The aforementioned techniques in our practice model can help overcome barriers related to adjustment in wearing the mask. Additionally, the mask may cause skin irritation. The patient should be asked about skin allergies before the prescription is written.

6 SUMMARY

The head and neck surgeon who wishes to practice sleep medicine is encouraged to become skilled at the history, upper respiratory tract physical examination, multi-channel home sleep testing and PAP therapies. Not only is this excellent and very satisfying patient care, it also brings substantial surgical opportunities to the practice. Snoring is the premier symptom of sleep disordered breathing, and typically the primary reason that prompts the patient to seek medical care. When a patient’s AHI is low and there are no co-morbidities present, snoring surgery can be successful. For those with more complex sleep disordered breathing, PAP therapy is a mandatory, first-line treatment. Those who fail PAP therapy should be considered for surgical therapy, either to make them more compliant or, anatomy permitting, to operate for cure. By incorporating PAP therapy paradigms into an ENT practice, treatment of SDB can achieve high therapeutic and compliance levels.

1. Sullivan CE, Issa FG, Berthon-Jones M, Eves L. Reversal of obstructive sleep apnoea by continuous positive airway pressure applied through the nares. Lancet. 1981;1(8225):862-865.

2. Sierpina VS, Philips B. Need for scholarly, objective inquiry into alternative therapies. Acad Med. 2001;76(9):863-865.

3. Golpe R, Jimenez A, Carpizo R. Home sleep studies in the assessment of sleep apnea/hypopnea syndrome. Chest. 2002;122(4):1156-1161.

4. Flemons WW, Littner MR, Rowley JA, et al. Home diagnosis of sleep apnea: a systematic review of the literature. An evidence review cosponsored by the American Academy of Sleep Medicine, the American College of Chest Physicians, and the American Thoracic Society. Chest. 2003;124(4):1543-1579.

5. Reichert JA, Bloch DA, Cundiff E, Votteri BA. Comparison of the NovaSom QSG, a new sleep apnea home-diagnostic system, and polysomnography. Sleep Med. 2003;4(3):213-218.

6. ATS/ACCP/AASM Taskforce Steering Committee. Executive summary on the systematic review and practice parameters for portable monitoring in the investigation of suspected sleep apnea in adults. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;169(10):1160-1163.

7. Souter MA, Stevenson S, Sparks B, Drennan C. Upper airway surgery benefits patients with obstructive sleep apnoea who cannot tolerate nasal continuous positive airway pressure. J Laryngol Otol. 2004;118(4):270-274.

8. Zafar S, Ayappa I, Norman RG, Krieger AC, Walsleben JA, Rapoport DM. Choice of oximeter affects apnea–hypopnea index. Chest. 2005;127(1):80-88.

9. d’Ortho MP, Grillier-Lanoir V, Levy P. Constant vs. automatic continuous positive airway pressure therapy: home evaluation. Chest. 2000;118(4):1010-1017.

10. Egan KK, Kim DW. A novel intranasal stent for functional rhinoplasty and nostril stenosis. Laryngoscope. 2005;115(5):903-909.

11. Barbosa Ade A, Caldas N, Morais AX, Campos AJ, Caldas S, Lessa F. Assessment of pre and postoperative symptomatology in patients undergoing inferior turbinectomy. Rev Bras Otorinolaringol (Engl edn). 2005;71(4):468-471.

12. Lorenzi-Filho G, Genta PR, Figueiredo AC, Inoue D. Cheyne–Stokes respiration in patients with congestive heart failure: causes and consequences. Clinics. 2005;60(4):333-344.

13. Giles TL, Lasserson TJ, Smith BJ, White J, Wright J, Cates CJ. Continuous positive airways pressure for obstructive sleep apnoea in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;25(1):CD001106.

14. Guilleminault C, Lin CM, Goncalves MA, Ramos E. Related articles. A prospective study of nocturia and the quality of life of elderly patients with obstructive sleep apnea or sleep onset insomnia. J Psychosom Res. 2004;56(5):511-515.

15. Haynes PL. The role of behavioral sleep medicine in the assessment and treatment of sleep disordered breathing. Clin Psychol Rev. 2005;25(5):673-705.

16. Kawahara S, Akashiba T, Akahoshi T, Horie T. Nasal CPAP improves the quality of life and lessens the depressive symptoms in patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Intern Med. 2005;44(5):422-427.

17. Guilleminault C, Lin CM, Goncalves MA, Ramos E. A prospective study of nocturia and the quality of life of elderly patients with obstructive sleep apnea or sleep onset insomnia. J Psychosom Res. 2004;56(5):511-515.

18. George CF. Reduction in motor vehicle collisions following treatment of sleep apnoea with nasal CPAP. Thorax. 2001;56(7):508-512.

19. Arias MA, Garcia-Rio F, Alonso-Fernandez A, Martinez I, Villamor J. Pulmonary hypertension in obstructive sleep apnoea: effects of continuous positive airway pressure A randomized, controlled cross-over study. Eur Heart J. 27(9):1106–13, 2006.

20. Dhillon S, Chung SA, Fargher T, et al. Sleep apnea, hypertension, and the effects of continuous positive airway pressure. Am J Hypertens. 2005;18(5 Pt 1):594-600.

21. Logan AG, Tkacova R, Perlikowski SM, et al. Refractory hypertension and sleep apnoea: effect of CPAP on blood pressure and baroreflex. Eur Respir J. 2003;21(2):241-247.

22. Haas DC, Foster GL, Nieto FJ. Age-dependent associations between sleep-disordered breathing and hypertension: importance of discriminating between systolic/diastolic hypertension and isolated systolic hypertension in the Sleep Heart Health Study. Circulation. 2005;111(5):614-621.

23. Poreba R, Derkacz A, Andrzejak R. Sleep apnea syndrome as a cause of secondary hypertension. A case report. Kardiol Pol. 2005;63(5):549-551.

24. Hassaballa HA, Tulaimat A, Herdegen JJ, Mokhlesi B. The effect of continuous positive airway pressure on glucose control in diabetic patients with severe obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep Breath. 2005;9(4):176-180.

25. Babu AR, Herdegen J, Fogelfeld L, Shott S, Mazzone T. Type 2 diabetes, glycemic control, and continuous positive airway pressure in obstructive sleep apnea. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165(4):447-452.

26. Harsch IA, Schahin SP, Bruckner K, et al. The effect of continuous positive airway pressure treatment on insulin sensitivity in patients with obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome and type 2 diabetes. Respiration. 2004;71(3):252-259.

27. Harsch IA, Schahin SP, Radespiel-Troger M, et al. Continuous positive airway pressure treatment rapidly improves insulin sensitivity in patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;169(2):156-162.

28. Robinson GV, Pepperell JC, Segal HC, Davies RJ, Stradling JR. Circulating cardiovascular risk factors in obstructive sleep apnoea: data from randomised controlled trials. Thorax. 2004;59(9):777-782.

29. Ip MS, Lam KS, Ho C, Tsang KW, Lam W. Serum leptin and vascular risk factors in obstructive sleep apnea. Chest. 2000;118(3):580-586.

30. Nelesen RA, Yu H, Ziegler MG, Mills PJ, Clausen JL, Dimsdale JE. Continuous positive airway pressure normalizes cardiac autonomic and hemodynamic responses to a laboratory stressor in apneic patients. Chest. 2001;119(4):1092-1101.

31. Ryan CF, Lowe AA, Li D, Fleetham JA. Magnetic resonance imaging of the upper airway in obstructive sleep apnea before and after chronic nasal continuous positive airway pressure therapy. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1991;144(4):939-944.

32. Kuzniar TJ, Gruber B, Mutlu GM. Cerebrospinal fluid leak and meningitis associated with nasal continuous positive airway pressure therapy. Chest. 2005;128(3):1882-1884.

33. Hess DR. Noninvasive positive-pressure ventilation and ventilator-associated pneumonia. Respir Care. 2005;50(7):924-929. discussion 929–31

34. Chasens ER, Pack AI, Maislin G, Dinges DF, Weaver TE. Claustrophobia and adherence to CPAP treatment. West J Nurs Res. 2005;27(3):307-321.

35. Nieto FJ, Young TB, Lind BK, et al. Association of sleep-disordered breathing, sleep apnea, and hypertension in a large community-based study. Sleep Heart Health Study. Jama. 2000;283(14):1829-1836.

36. Peppard PE, Young T, Palta M, Skatrud J. Prospective study of the association between sleep-disordered breathing and hypertension. N Engl J Med. 2000;342(19):1378-1384.

37. Lavie P, Herer P, Hoffstein V. Obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome as a risk factor for hypertension: population study. BMJ. 2000;320(7233):479-482.

38. Javaheri S, Parker TJ, Liming JD, et al. Sleep apnea in 81 ambulatory male patients with stable heart failure. Types and their prevalences, consequences, and presentations. Circulation. 1998;97(21):2154-2159.

39. Trupp RJ, Hardesty P, Osborne J, et al. Prevalence of sleep disordered breathing in a heart failure program. Congest Heart Fail. 2004;10(5):217-220.

40. Sin DD, Fitzgerald F, Parker JD, Newton G, Floras JS, Bradley TD. Risk factors for central and obstructive sleep apnea in 450 men and women with congestive heart failure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;160(4):1101-1106.

41. Laaban JP, Pascal-Sebaoun S, Bloch E, Orvoen-Frija E, Oppert JM, Huchon G. Left ventricular systolic dysfunction in patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Chest. 2002;122(4):1133-1138.

42. Hanly P, Sasson Z, Zuberi N, Lunn K. ST-segment depression during sleep in obstructive sleep apnea. Am J Cardiol. 1993;71(15):1341-1345.

43. Schafer H, Koehler U, Ploch T, Peter JH. Sleep-related myocardial ischemia and sleep structure in patients with obstructive sleep apnea and coronary heart disease. Chest. 1997;111(2):387-393.

44. Mooe T, Franklin KA, Wiklund U, Rabben T, Holmstrom K. Sleep-disordered breathing and myocardial ischemia in patients with coronary artery disease. Chest. 2000;117(6):1597-1602.

45. Mooe T, Franklin KA, Holmstrom K, Rabben T, Wiklund U. Sleep-disordered breathing and coronary artery disease: long-term prognosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164(10 Pt 1):1910-1913.

46. Peker Y, Hedner J, Kraiczi H, Loth S. Respiratory disturbance index: an independent predictor of mortality in coronary artery disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;162(1):81-86.

47. Becker H, Brandenburg U, Peter JH, Von Wichert P. Reversal of sinus arrest and atrioventricular conduction block in patients with sleep apnea during nasal continuous positive airway pressure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995;151(1):215-218.

48. Koehler U, Becker HF, Grimm W, Heitmann J, Peter JH, Schafer H. Relations among hypoxemia, sleep stage, and bradyarrhythmia during obstructive sleep apnea. Am Heart J. 2000;139(1 Pt 1):142-148.

49. Gami AS, Pressman G, Caples SM, et al. Association of atrial fibrillation and obstructive sleep apnea. Circulation. 2004;110(4):364-367.

50. Atwood CWJr., McCrory D, Garcia JG, Abman SH, Ahearn GS. Pulmonary artery hypertension and sleep-disordered breathing: ACCP evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2004;126(1 Suppl):72S-77S.

51. Dyken ME, Somers VK, Yamada T, Ren ZY, Zimmerman MB. Investigating the relationship between stroke and obstructive sleep apnea. Stroke. 1996;27(3):401-407.

52. Good DC, Henkle JQ, Gelber D, Welsh J, Verhulst S. Sleep-disordered breathing and poor functional outcome after stroke. Stroke. 1996;27(2):252-259.

53. Parra O, Arboix A, Bechich S, et al. Time course of sleep-related breathing disorders in first-ever stroke or transient ischemic attack. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;161(2 Pt 1):375-380.

54. Alberti A, Mazzotta G, Gallinella E, Sarchielli P. Headache characteristics in obstructive sleep apnea syndrome and insomnia. Acta Neurol Scand. 2005;111(5):309-316.

55. Goder R, Friege L, Fritzer G, Strenge H, Aldenhoff JB, Hinze-Selch D. Morning headaches in patients with sleep disorders: a systematic polysomnographic study. Sleep Med. 2003;4(5):385-391.

56. Ip MS, Lam B, Ng MM, Lam WK, Tsang KW, Lam KS. Obstructive sleep apnea is independently associated with insulin resistance. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;165(5):670-676.

57. Harsch IA, Schahin SP, Radespiel-Troger M, et al. Continuous positive airway pressure treatment rapidly improves insulin sensitivity in patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;169(2):156-162.

58. Punjabi NM, Shahar E, Redline S, Gottlieb DJ, Givelber R, Resnick HE. Sleep-disordered breathing, glucose intolerance, and insulin resistance: the Sleep Heart Health Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;160(6):521-530.

59. Vgontzas AN, Bixler EO, Chrousos GP. Sleep apnea is a manifestation of the metabolic syndrome. Sleep Med Rev. 2005;9(3):211-224.

60. Svatikova A, Wolk R, Gami AS, Pohanka M, Somers VK. Interactions between obstructive sleep apnea and the metabolic syndrome. Curr Diab Rep. 2005;5(1):53-58.

61. Demeter P, Pap A. The relationship between gastroesophageal reflux disease and obstructive sleep apnea. J Gastroenterol. 2004;39(9):815-820.

62. Green BT, Broughton WA, O’Connor JB. Marked improvement in nocturnal gastroesophageal reflux in a large cohort of patients with obstructive sleep apnea treated with continuous positive airway pressure. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(1):41-45.

63. Kerr P, Shoenut JP, Millar T, Buckle P, Kryger MH. Nasal CPAP reduces gastroesophageal reflux in obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Chest. 1992;101(6):1539-1544.

64. Berg S, Hoffstein V, Gislason T. Acidification of distal esophagus and sleep-related breathing disturbances. Chest. 2004;125(6):2101-2106.

65. Margel D, Cohen M, Livne PM, Pillar G. Severe, but not mild, obstructive sleep apnea syndrome is associated with erectile dysfunction. Urology. 2004;63(3):545-549.

66. Goncalves MA, Guilleminault C, Ramos E, Palha A, Paiva T. Erectile dysfunction, obstructive sleep apnea syndrome and nasal CPAP treatment. Sleep Med. 2005;6(4):333-339.

67. Hajduk IA, Strollo PJJr., Jasani RR, Atwood CWJr., Houck PR, Sanders MH. Prevalence and predictors of nocturia in obstructive sleep apnea–hypopnea syndrome – a retrospective study. Sleep. 2003;26(1):61-64.

68. Umlauf MG, Chasens ER. Sleep disordered breathing and nocturnal polyuria: nocturia and enuresis. Sleep Med Rev. 2003;7(5):403-411.