Chapter 8 Course and management of childbirth

CHOICES IN CHILDBIRTH

With the trend towards hospital birth in the developed countries, some groups of women question whether this is always appropriate, claiming that on admission to hospital a pregnant woman loses her autonomy, may not be told about proposed procedures, and can be treated impersonally by busy attending staff. In other words, a normal event is medicalized. Several international organizations have addressed the issues raised by women and made recommendations, which are summarized in Box 8.1.

Box 8.1 Childbirth recommendations

The criticisms advanced by women’s groups have had an effect on obstetric practice and the childbirth choices now provided in many places (Box 8.2).

Prepared participatory childbirth

In this approach the parents undertake childbirth training, learning about the processes of childbirth and how to accept the pains of uterine contractions (see pp. 49–50). Labour is managed by trained staff, and the principles mentioned earlier are observed by both staff and patients. The birth takes place in a quiet environment and the baby is given to the mother at once so that she may offer suckling and celebrate the birth.

Actively managed childbirth

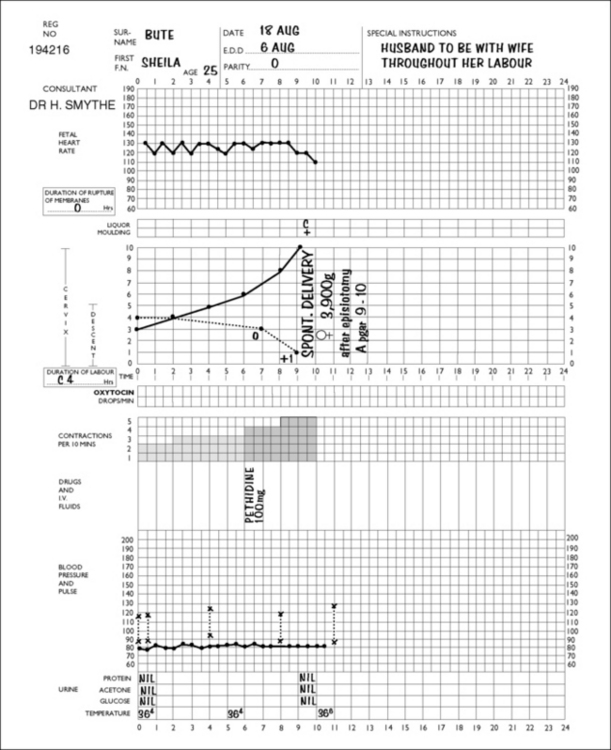

On admission to the delivery unit, the diagnosis of labour is either confirmed or rejected. If the woman is in labour, the time of admission is designated as the start of labour. A partogram is started and the progress of labour is marked on it (Fig. 8.1). Vaginal examinations are made every 2–4 hours and the cervical dilatation is recorded on the partogram. Action lines, printed on transparent plastic, are superimposed on the partogram (Fig. 8.2). In the active stage of labour the slowest acceptable rate of cervical dilatation is 1 cm/h. If the cervical dilatation lies to the right of the appropriate action line the membranes are ruptured and an incremental dilute oxytocin infusion is established in nulliparous women (and some multiparous women), provided that a single fetus presents as a vertex and there are no signs of fetal distress.

Elective caesarean section

A small but increasing number of women, particularly those over the age of 35, inform their obstetrician during pregnancy that they wish to be delivered by caesarean section. The obstetrician should listen to the woman and discern the underlying reasons for her request. For some it may be a fear of the pain of labour, for others to avoid any risk of pelvic floor damage during delivery, or a perception that abdominal delivery removes all risks for the baby. It is particularly important that the risks of caesarean versus vaginal delivery are carefully explained (Box 8.3). If the woman confirms that she wishes to be delivered by caesarean section, the obstetrician should either agree to her wish or arrange for a consultation with another colleague.

Box 8.3 Effects of caesarean section compared with vaginal birth

Adapted from Caesarean Section, National Collaborating Centre for Women’s and Children’s Health. 2004. RCOG Press www.rcog.org.uk. Full details of absolute and relative risks can be obtained from full guideline.

| Increased | No difference | Decreased |

|---|---|---|

| Abdominal pain | Blood loss >1000 ml | Perineal pain |

| Bladder and ureteric injury | Infection-wound or endometritis | Urinary incontinence |

| Need for laparotomy or D&C | Genital tract injury | Uterovaginal prolapse |

| Hysterectomy | Back pain | |

| ICU admission | Dyspareunia | |

| Thromboembolism | Postnatal depression | |

| Length of hospital stay | Neonatal morbidity (excluding breech) | |

| Readmission | Neonatal intracranial haemorrhage | |

| Placenta praevia | Brachial plexus palsy | |

| Uterine rupture | Cerebral palsy | |

| Maternal death | ||

| Stillbirth in future pregnancies | ||

| Secondary infertility | ||

| Neonatal respiratory morbidity |

ONSET OF LABOUR

Onset of true labour

Duration of labour

The duration of labour is not easy to determine precisely as its onset is often indefinite and subjective (Box 8.4). In studies of informed women whose labour started spontaneously there was a wide variation in the duration of labour, as can be seen in Table 8.1.

| NULLIPARAE | MULTIPARAE | |

|---|---|---|

| 1st stage | 8.25 (2–12) | 5.5 (1–9) |

| 2nd stage | 1 (0.25–1.5) | 0.25 (0–0.75) |

| 3rd stage | 0.25 (0–1)9.5 (2.25–14) | 0.25 (0–0.5)6 (1–10.25) |

PROGRESS AND MANAGEMENT OF LABOUR AND BIRTH

The management of labour begins when the woman seeks admission to hospital, which she does when she believes or knows that she is in labour. As labour is a time of anxiety and stress, the attitude of the member of staff who admits her is most important. The care of the woman during her labour and childbirth may be conducted by a midwife (see also p. 66), or by midwives in partnership with an obstetrician or a general practitioner.

Admission

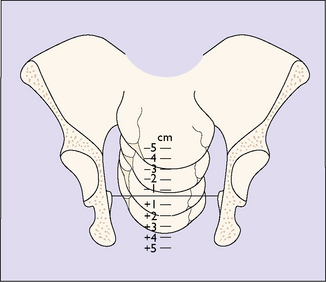

A general examination is made by a midwife or a doctor, the blood pressure, pulse and temperature being recorded. The abdomen is palpated to determine the presentation of the fetus and the position of the presenting part in relation to the pelvic brim (see Fig. 6.17). A vaginal examination may be carried out, with aseptic precautions, to determine the effacement and dilatation of the cervix and the position and station of the presenting part. The station of the presenting part is the level of the lowest fetal bony part (head or breech) in relation to an imaginary line joining the mother’s ischial spines. It is measured in centimetres above or below the ischial spines (Fig. 8.3). If the amniotic sac (the membranes) has ruptured this is noted. Evidence does not support the common practice of performing a routine 20-minute cardiotocogram (CTG) on admission in low-risk women. The ‘admission CTG’ is associated with higher intervention rates, i.e. augmentation of labour, epidural analgesia and operative delivery, without a clear improvement in neonatal outcome. The woman is transferred from the admission room to a bed in a delivery room (if she has not already been admitted to it) and a partogram is started which shows the progress of labour at a glance.

First stage of labour

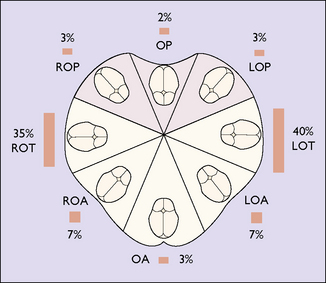

At the beginning of the first stage of labour the fetal presenting part (usually it is the head, so this term will be used in the rest of this chapter instead of the presenting part) has descended into the true pelvis to some extent. In a normally shaped pelvis the position of the occiput is in the transverse diameter of the pelvis in 75% of cases, in the oblique in 14% of cases, in the direct anterior position in 3% of cases, and in a posterior diameter in 8% of cases (Fig. 8.4).

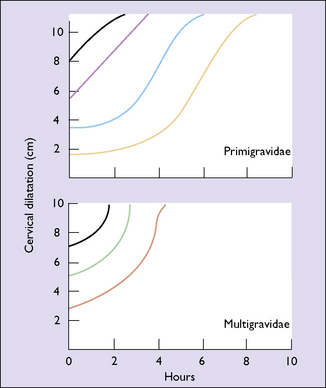

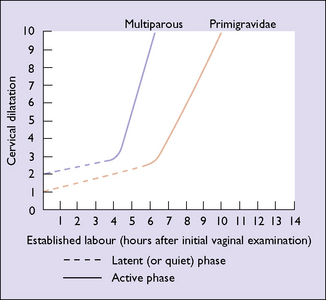

The duration of the latent and active phases is shown in Figure 8.5. If they last for more than 12 hours in a nulliparous woman, or more than 9 hours in a multiparous woman, the cause should be investigated (see Ch. 21).

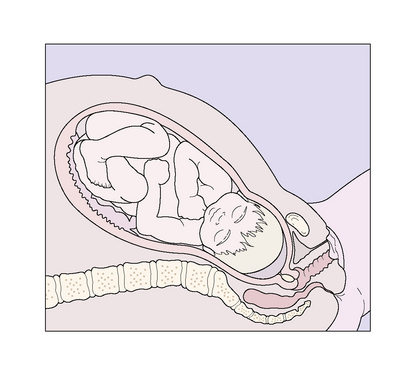

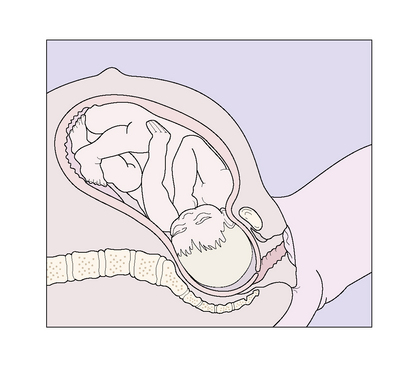

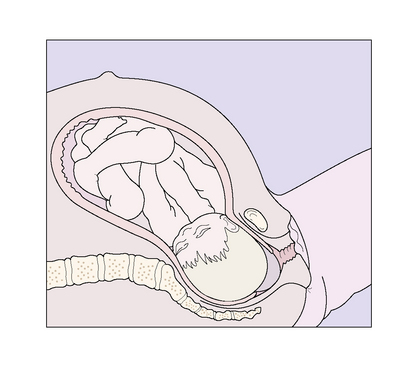

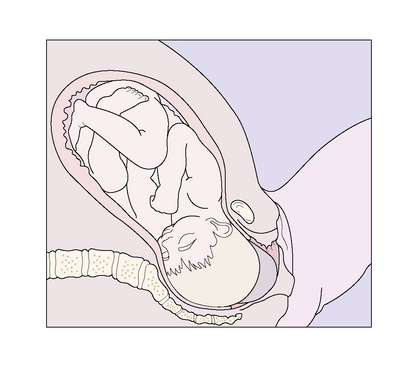

During the active part of the first stage of labour, the fetal head descends more deeply into the maternal pelvis and flexes (Figs 8.6–8.8).

Specific care in the first stage

The following steps should be followed:

Second stage of labour

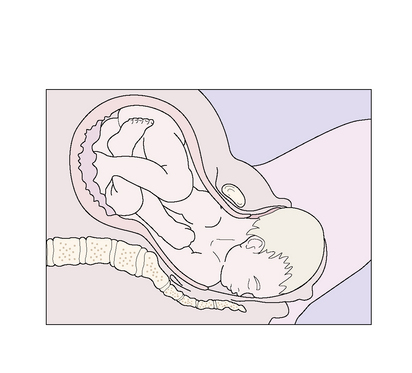

The second stage of labour begins when the cervix is fully dilated, to complete the formation of the curved birth canal, and ends with the birth of the baby. The second stage of labour is the expulsive stage, during which the fetus is forced through the birth canal. The uterine contractions become more frequent, recurring at 2–5-minute intervals, and are stronger, lasting 60–90 seconds. The fetal head descends deeply into the pelvis and, on reaching the gutter-shaped pelvic floor, rotates anteriorly (internal rotation) so that the occiput lies behind the symphysis pubis (Fig. 8.9). Anterior rotation occurs in 98% of cases, although in 2% of cases the head rotates posteriorly, with the result that the occiput lies in front of the sacrum.

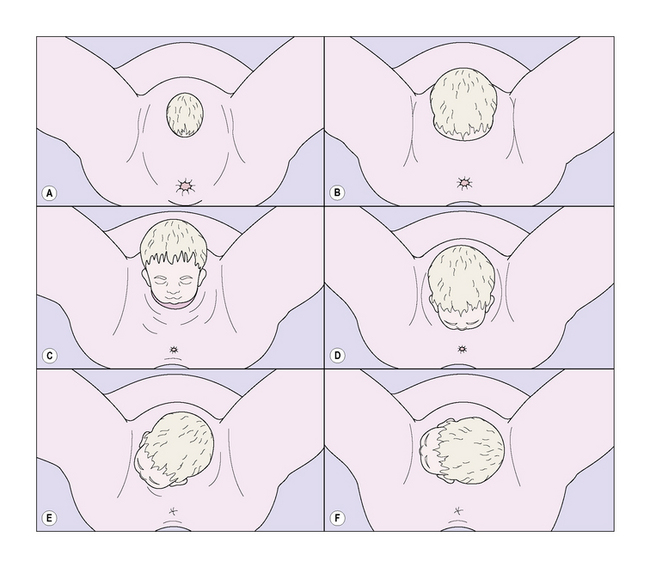

As the fetal head is pushed deeper into the pelvis the patient may complain of intense pressure on her rectum or pains radiating down her legs, caused by pressure on the sacral nerve plexus or obturator nerve. Some 15 minutes later the anus begins to open, exposing its anterior wall, and the head can be seen inside the vagina. With each contraction the fetal head becomes a little more visible, retreating a little between contractions but advancing slightly all the time (Fig. 8.10).

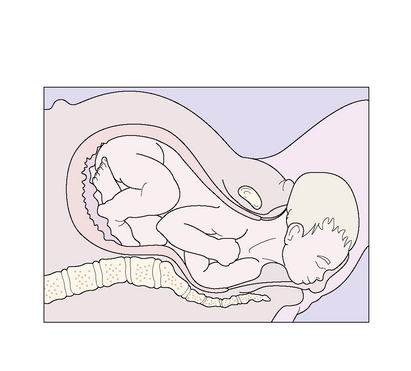

The head now presses on the posterior wall of the lower vagina and the perineum becomes thinner and stretched, its skin tense and shining. The woman complains of a ‘bursting’ feeling and a desire to push even without a uterine contraction. Soon a large part of the head can be seen between the stretched labia, and the parietal bosses become visible. The further sequence of the birth is shown in Figures 8.11 and 8.12, and is now described. With an extra effort the baby’s head is born, extending at the neck so that the forehead, the nose, the mouth and the chin appear in sequence. Mucus streams from the baby’s mouth and nose. After a short pause, the head rotates into a transverse diameter (external rotation). This brings the shoulders into the anterior–posterior diameter of the lower pelvis. The shoulders are born next, the anterior shoulder stemming from behind the symphysis and the posterior shoulder rolling over the perineum, followed by the baby’s trunk and legs. The baby gasps once or twice and cries vigorously. The uterus contracts to a size found at 20 weeks’ gestation.

BIRTH OF THE BABY

Shoulders

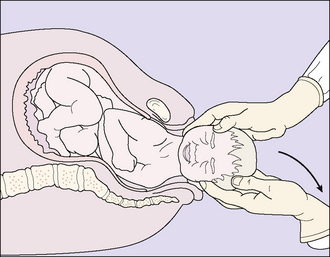

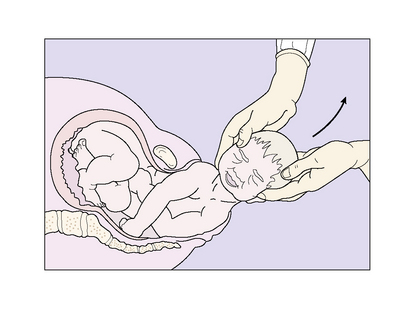

As the baby’s head rotates, mucus streams from its mouth and nose. With the next contraction, the rotated head is grasped gently between the attendant’s two hands, which are placed over the sides of the head, and the head is drawn posteriorly so that the anterior shoulder is released from behind the pubic bones (Fig. 8.13). Following the birth of the anterior shoulder, the baby is swept upwards in an arc to release the posterior shoulder, followed by the body and the legs (Fig. 8.14).

THE NEWBORN BABY

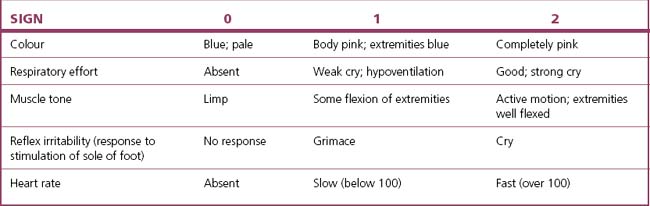

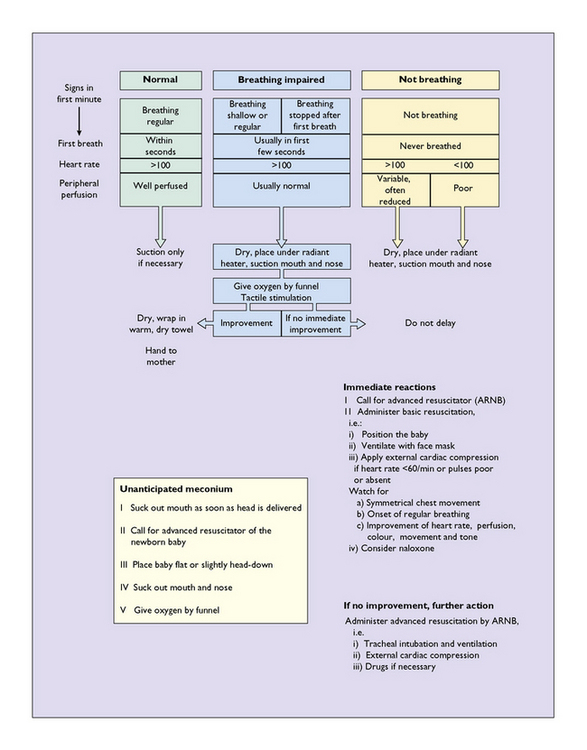

The neonate lies between its mother’s legs, usually taking its first breath within seconds, and starting to cry and to move its arms and legs. It is checked for good respiratory effort, its colour and its alertness. Either an Apgar score is taken (Table 8.2) or the Basic Resuscitation Programme suggested in the UK is adopted (Fig. 8.15). Most babies establish respiration easily and quickly, but a few are born in a mild or severe hypoxic state. This problem is discussed further in Chapter 26. The baby is checked for gross malformations. It is then given to the mother for cuddling and suckling. This early mother–baby contact encourages (but is not essential for) bonding, and if the baby is put to the breast this helps to ‘bring in’ the milk.

Vitamin K

Most neonates develop vitamin K deficiency by the third day of life. This predisposes the baby to a bleeding diathesis (haemorrhagic disease of the newborn) caused by the depression of clotting factors II, VII, IX and X. The baby may bleed from the gastrointestinal tract, the umbilical cord, or from skin punctures. A late-onset variety of vitamin K deficiency may affect breastfed babies between 4 and 6 weeks after birth. It manifests as gastrointestinal bleeding or intracranial haemorrhage. To prevent these possible problems it is currently recommended that all newborn babies should be given phytomenadione (vitamin K1), either 1.0 mg intramuscularly at birth or 1.0 mg orally at birth, at 3–4 days and at 6 weeks of age. The further care of the newborn infant is described in Chapter 9.

PROGRESS, MANAGEMENT AND DELIVERY OF THE PLACENTA

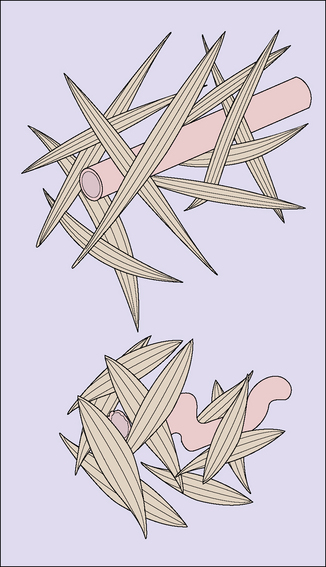

Separation of the placenta takes place through the spongy layer of the decidua basalis, as the result of uterine contractions being added to the retraction of the uterus that follows the birth of the child. The retraction of the uterus reduces the size of the placental bed to one-quarter of its size in pregnancy, with the result that the placenta buckles inwards, tearing the blood vessels of the intervillous space and causing a retroplacental haemorrhage, which further separates the placenta. The process starts as the baby is born and separation is usually complete within 5 minutes, but the placenta may be held in the uterus for longer because the membranes take longer to strip from the underlying decidua. Following the separation of the placenta, the lattice arrangements of the myometrial fibres effectively strangle the blood vessels supplying the placental bed, reducing further blood loss and encouraging the formation of fibrin plugs in their torn ends (Fig. 8.16).

Management of the third stage of labour

There are two methods of managing the third stage of labour:

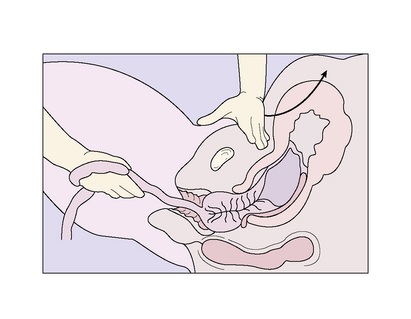

Active management

The delivery of the baby following the injection is conducted slowly over 60 seconds. The umbilical cord is divided and clamped 2 minutes after the birth. The slowness is because the oxytocic effect takes about 2 minutes to produce a strong uterine contraction. The attendant’s left hand is placed on the uterus to detect the contraction. When it occurs, the hand is placed suprapubically and pushes the uterus upwards while the right hand grasps the umbilical cord and pulls the placenta out of the vagina in a controlled manner (Fig. 8.17). The membranes are drawn out intact by twisting them into a rope and pulling them out with a sponge forceps or the hand. In 1–2% of cases the placenta is retained, but no blood loss occurs. After a 10-minute delay another attempt is made to pull the placenta out by controlled cord traction. If this fails, manual removal is necessary (see p. 184).

Retained placenta

INSPECTION AND REPAIR OF THE GENITAL TRACT AND PERINEUM

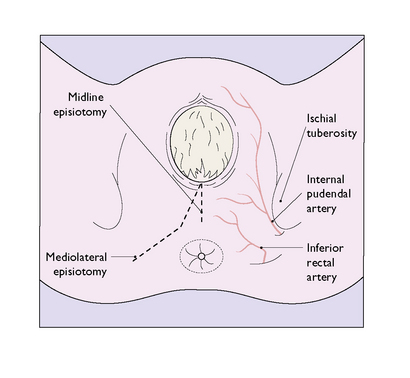

Episiotomy

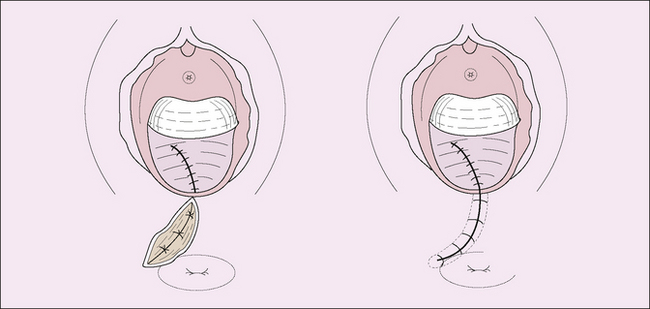

If the accoucheur thinks that an episiotomy is required because the fetal head is overdistending the woman’s perineum, they should explain what they propose to the patient. If the woman agrees to the procedure, the perineum should be infiltrated with a local anaesthetic, unless the woman has already had an epidural anaesthetic. The episiotomy incision may be midline or mediolateral (Fig. 8.18). The midline incision has the advantage that no large blood vessels are encountered and it is easier to repair. Its disadvantage is that it may extend into the rectum. If a large episiotomy is needed, for example when a difficult midforceps delivery is anticipated, a mediolateral episiotomy is preferred.

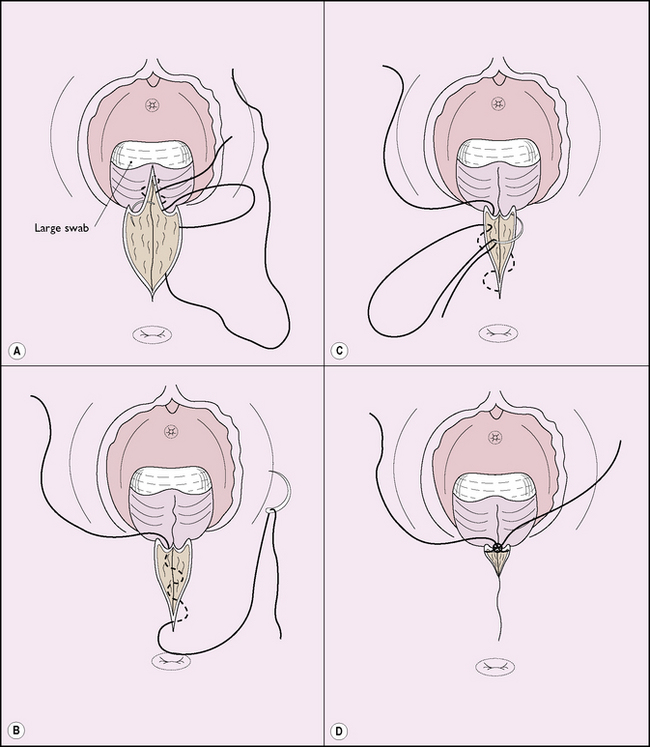

One method of repairing an episiotomy is shown in Figure 8.19. This repair is the least painful postoperatively, particularly when 2/0 polyglycolic suture material is used.

Another method is to use continuous suture to repair the vagina and interrupted sutures for the perineal muscles and skin; a continuous subcuticular skin closure is associated with less pain and dyspareunia 3 months postpartum. The standard repair of an episiotomy is shown in Figure 8.20.

Perineal tears

Four degrees of perineal tear are recognized:

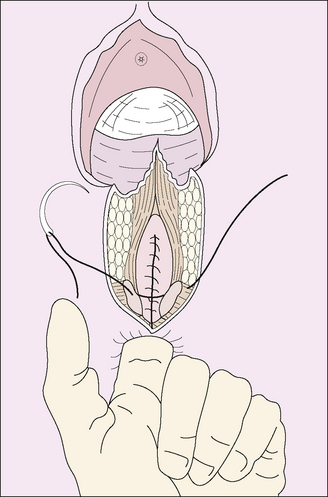

First-degree tears are easy to repair; one or two sutures are all that is needed. Second- and third-degree tears need more care and their repair is shown in Figure 8.20. Third- and fourth-degree tears are uncommon, occurring in less than 1% of births. They usually follow a forceps delivery in a primigravida, the birth of a baby weighing more than 4 kg, or the delivery of a fetus persistently maintaining an occipitoposterior position. Careful repair is essential, but even then half of the women have persisting anal incontinence (usually only of flatus) for about 6 months owing to poorly repaired sphincter damage, and 4% have faecal incontinence. Pelvic exercises may resolve the problem, but if these fail surgery may be needed. Repair of fourth-degree tears requires considerable skill, and it is essential to secure the apex of the tear otherwise a rectovaginal fistula may result. The anal sphincter retracts when torn and its exposed ends must be identified and rejoined by sutures (Fig. 8.21).

Lacerations of the lower genital tract

After a difficult delivery the vagina and the clitoral area should be inspected for lacerations. Any large laceration should be sutured. Continued bleeding in spite of a firmly contracted uterus suggests an internal laceration. The vagina and cervix should be inspected with good illumination. If a lacerated cervix is found the tear is sutured, care being taken to include the apex of the tear (Fig. 8.22).

MANAGEMENT OF THE IMMEDIATE POSTDELIVERY PERIOD

The woman should remain in the delivery room for 1 hour. The medical attendants will check regularly that the uterus is contracted, that there is no excessive blood loss and that the vital signs are normal. During this time the baby will be checked thoroughly for abnormalities (see pp. 86–88), cleansed and returned to the mother to enable the parents to celebrate the birth.

Before the woman leaves the delivery room, the attendant must be sure that:

PAIN RELIEF DURING LABOUR AND CHILDBIRTH

The ideal obstetric method of pain relief should:

Local analgesia

Nerve supply of the vulva

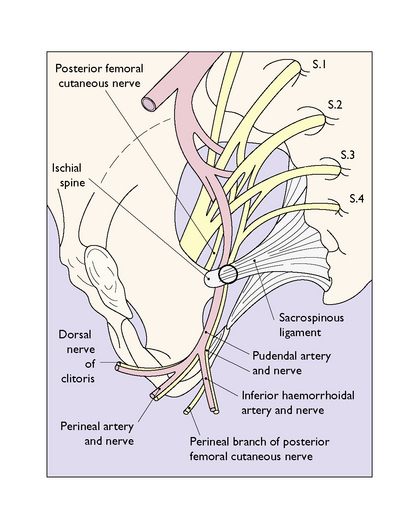

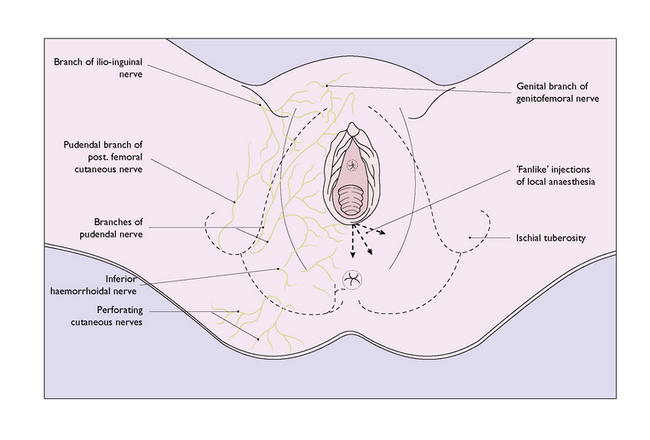

The female vulva is innervated mainly by branches of the pudendal nerve. The pudendal nerve, derived from S2, S3 and S4, leaves the pelvis medial to the sciatic nerve through the greater sciatic foramen. It then crosses the external surface of the ischial spine and re-enters the pelvis through the lesser sciatic notch and, passing along the lateral wall of the ischiorectal fossa, divides into branches that supply most of the perineum (Fig. 8.23). Further sensory branches to the skin of the perineum are derived from the ilioinguinal nerve, the pudendal branch of the posterior femoral cutaneous nerve and the genital branch of the genitofemoral nerve (Fig. 8.24).

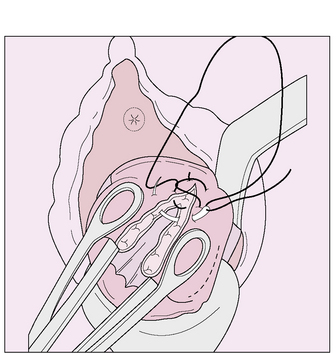

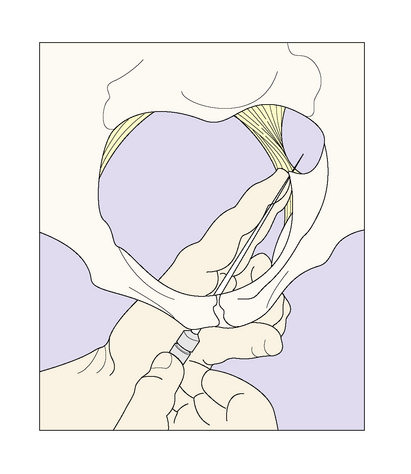

Technique of pudendal nerve block

A 10 cm 20-gauge needle and, if available, a needle director are required. Two fingers are introduced into the vagina to palpate the ischial spine, the guide containing the needle being introduced in the groove between the index and middle finger to impinge on the spine. The guide is then directed to lie just medial to, and below, the ischial spine, and the needle is advanced 1 cm beyond the guide (if no guide is available the needle is introduced between the fingers to the same site) and pushed through the sacrospinous ligament (Fig. 8.25); 10 mL of 0.5% lidocaine (lignocaine) are injected behind each ischial spine, and a further 10 mL are used to make a perineal infiltration. Anaesthesia should be effective within 5 minutes and it should be tested. The lower vagina and perineum become insensitive to pain. The use of pudendal nerve block is not without problems. For example, the needle may be difficult to introduce accurately in a relatively mobile patient, particularly when the fetal head is deeply engaged.

Technique of perineal nerve infiltration

Using a 7.5 cm 22-gauge needle and 20 mL of 0.5–1.0% lidocaine (lignocaine) the perineum is infiltrated in a fan-like manner, the base being the posterior fourchette at the midline. Three lines of infiltration are required, one medially as far as the anal sphincter and midway between the skin and the vaginal mucosa, and two others at 45 ° to block the nerves as they reach the perineum (Fig. 8.25). The analgesia is effective in about 3 minutes and lasts between 45 and 90 minutes. It should be tested by pricking the skin with a sharp needle before any procedure is begun.