Chapter 21 Correction of nasal obstruction due to nasal valve collapse

1 INTRODUCTION

Airway obstruction or difficulty breathing through the nose is one of the most frequent complaints presented to an otolaryngologist. Nasal septal deviation and turbinate hypertrophy are easily identified as areas of anatomic obstruction. One area that can be overlooked as an etiology for obstruction is an incompetent nasal valve. Nasal valve obstruction can markedly reduce airflow through the anterior nostril. This reduction in flow can contribute to snoring. A patient who complains of snoring is indicating that something more serious may be occurring. Snoring can present as a symptom of obstructive sleep apnea. Many people who snore also admit to excessive daytime sleepiness and fatigue.1

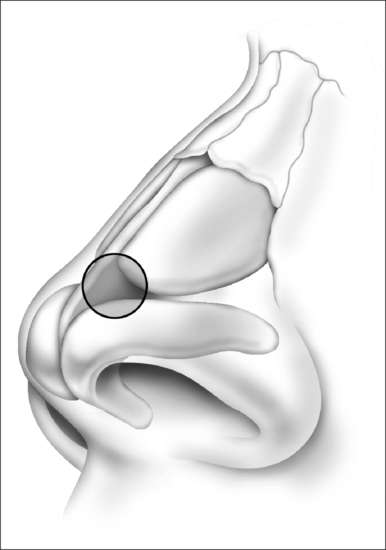

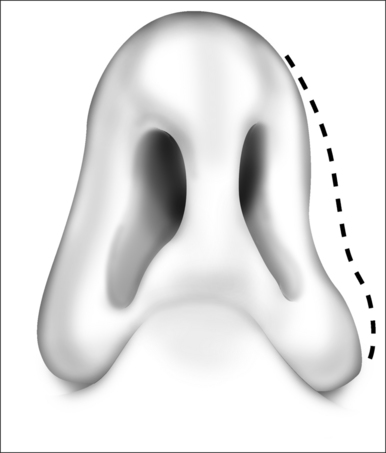

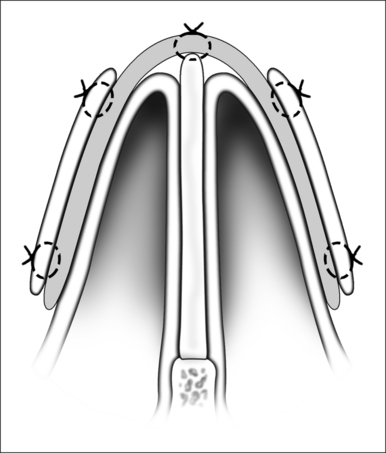

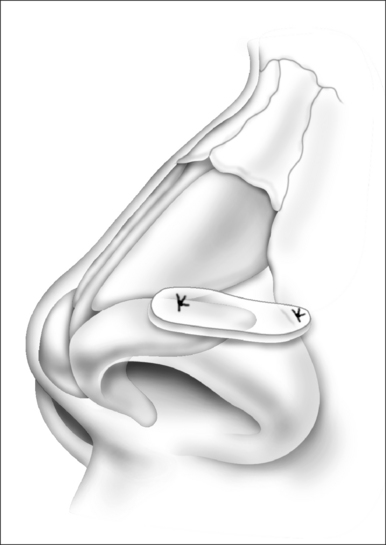

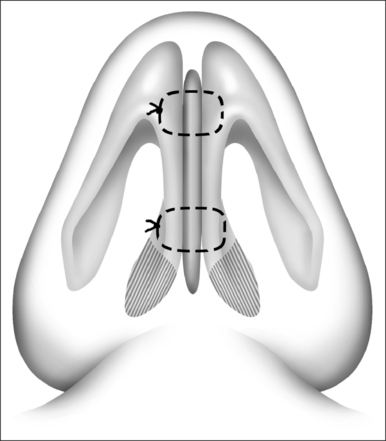

The internal valve is the area in which the septum articulates with the lower border of the upper lateral cartilage (Fig. 21.1A). The angle of this area is normally 10° to 15°. Minimal reduction in this angle can substantially restrict nasal airflow. The external nasal valve is an area composed of the alar or lower lateral cartilage with its associated cutaneous support as a mobile alar wall (Fig. 21.1B). It is bordered superiorly by the caudal edge of the upper lateral cartilages, inferiorly by the nasal floor, and posteriorly by the inferior turbinate. Laterally it is supported by the pyriform aperture of the maxilla and fibrofatty tissue of the ala.2

In consideration of surgical approaches to correct nasal obstruction, all possible causes must be entertained. Correction of septal deviation alone may not alleviate obstruction. Valvular effects may equal or surpass a deviation of the septum as the cause of airflow obstruction. In an excellent study by Constantain it was shown that septoplasty in addition to internal and external valve reconstruction offered the best relief in nasal obstruction. This combined approach offered significantly improved airflow in comparison to septoplasty alone.3

2 EXAMINATION

Examination before and after the application of topical vasoconstrictors can allow the effects of turbinate hyperplasia to be evaluated. The use of a standard nasal speculum spreads the valve open and can allow a narrowed valve to go undetected. An otoscope is a useful tool to evaluate internal valve collapse as it dose not splay open the area of concern. Some advocate the use of a Q-tip or cerumen spoon to elevate the sidewall of the nose 1–2 mm. If the patient reports improved breathing with this conservative maneuver, valve restriction is contributing to the patient’s obstruction.4 It is important to evaluate the competence of both the internal and the external nasal valves as concurrent correction is often required in order to alleviate the symptoms of nasal obstruction.

3 SURGICAL APPROACHES

3.1 INTERNAL NASAL VALVE

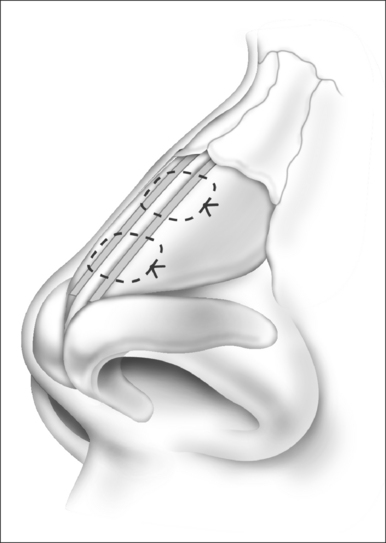

The spreader graft as described by Sheen in 19845 has been the most common approach to correct internal nasal valve collapse. Several adaptations to this technique have been reported in the literature.6–9 Each offers a varying twist of the standard that may accommodate specific circumstances pertaining to individual patients. An open approach is preferable as it allows superior visualization of anatomy.

3.1.1 TECHNIQUES FOR INTERNAL VALVE REPAIR

Spreader graft

Cartilage spanning graft

This technique is advantageous in elderly patients with thin septal cartilages. It can also be used in patients with thick skin. The disadvantage of this method is that the tip is made to appear wider, and may not be acceptable to a cosmetic rhinoplasty patient or patients with thin skin.

Splay conchal graft1,10,11

3.1.2 TECHNIQUES TO RECONSTRUCT THE EXTERNAL NASAL VALVE

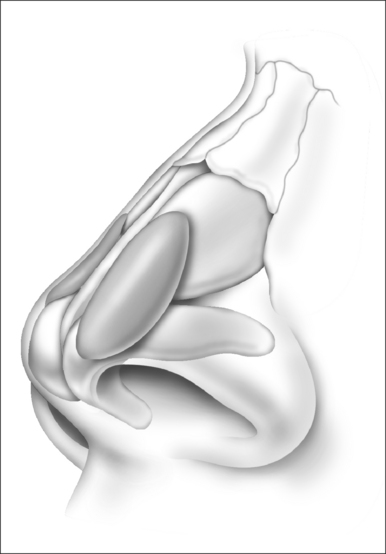

Alar batten graft2,12,13

Columelloplasty

The width of the columella often plays an important role in narrowing the nostril. Strengthening the columella and narrowing the footplates can improve nasal airflow.14

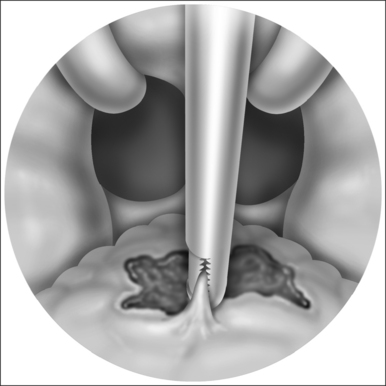

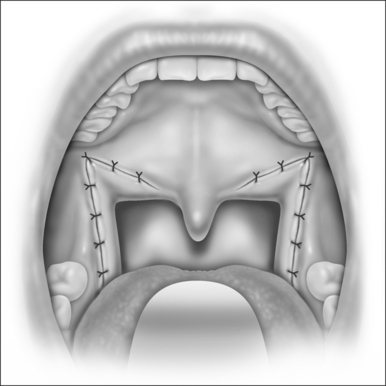

Nasal valve suspension technique

This technique is a simple approach, providing an internal suspension suture to elevate the nasal valve. It is most beneficial for the treatment of internal nasal valve collapse but I have seen improvement in external valve collapse also. The technique involves anchoring sutures into the inferior orbital rim and guiding sutures to suspend the nasal valve. Cartilage harvesting is not involved. The technique was originally described by Paniello15 and advancements in this technique have been described over the years.16

Technique

In summary, no one procedure will be applicable to all patients. Knowledge of a variety of techniques is essential in order to customize your approach to correct the patient’s specific defect.

1. Akcam T, Freidman O, Cook T. The effect on snoring of structural nasal valve dilation with a butterfly graft. Arch Oto Head Neck Surgery. 2004;130:1313-1318.

2. Kosh M., Jen A., Honrado C., Pearlman S. Nasal valve reconstruction. Arch Facial Plastic Surg. 2004;6:167-171.

3. Constantain M, Clardy R. The relative importance of septal and nasal valvular surgery in correcting airway obstruction in primary and secondary rhinoplasty. Plastic Reconst Surg. 1996;98(1):38-58.

4. Becker D., Becker S. Treatment of nasal obstruction from nasal valve collapse with alar batten grafts. J Long-Term Effects of Med Implants. 2003;13(3):259-269.

5. Sheen JH. Spreader graft: a method of reconstructing the roof of the middle nasal vault following rhinoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1984;73:230-239.

6. Ozturan O. Techniques for improvement of the internal nasal valve in functional-cosmetic nasal surgery. Acta Otolaryngol. 2000;120:312-315.

7. Andre R, Paun S, Vuyk H. Endonasal spreader graft placement as treatment for internal nasal valve insufficiency. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2004;6:36-40.

8. Gupta A, Brooks D, Stager S, Lindsey W. Surgical access to the internal nasal valve. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2003;5:155-158.

9. Boccieri A. Mini spreader grafts: a new technique associated with reshaping of the nasal tip. Plastic Reconst Surg. 2005;116(5):1525-1534.

10. Deylamipour M, Azarhoshandh A, Karimi H. Reconstruction of the internal nasal valve with a splay conceal graft. Plastic Reconst Surg. 2005;116(3):712-722.

11. Stucker F, Lian T, Karen M. Management of the keel nose and associated valve collapse. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2002;128:842-846.

12. Kalan A, Kenyon G, Seemungal T. Treatment of external nasal valve (alar rim) collapse with an alar strut. J Laryngol Otol. 2001;115:788-791.

13. Romo III T, Sclafani A, Sabini P. Use of porous high density polyethylene in revision rhinoplasty and in the plattyrrhine nose. Aesth Plast Surg. 1998;22:211-221.

14. Ghidini A, Dallari S, Marchioni D. Surgery of the nasal columella in external valve collapse. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2002;11:701-703.

15. Paniello R. Nasal valve suspension. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1996;122:1342-1346.

16. Friedman M, Ibrahim H, Syed Z. Nasal valve suspension: an improved, simplified technique for nasal valve collapse. Laryngoscope. 2003;113:381-385.