CHAPTER 18 Correction of Mal-United Intra-Articular Distal Radius Fractures with an Inside-Out Osteotomy Technique

Rationale and Basic Science Pertinent to the Procedure

The benefits of early correction of mal–united extra–articular distal radius fractures are well known.1 Obviously, when the mal–union affects also the joint surface the altered mechanics2 will lead to rapid radiocarpal osteoarthritis in young active individuals.3–5 Although this articular disruption calls for immediate correction, there are just a few papers that deal with the problem.4,6–8 Recently, Ring et al.8 reported good results by using a direct open approach. The technique is difficult, however, and there is a risk of causing additional damage due to the limited access to the joint space through a capsulotomy incision. Furthermore, devascularization of the fracture fragments due to detachment from their soft–tissue attachments is possible.

We have performed an open osteototomy for correction of mal–united intra–articular distal radius fractures several times. We have been limited to performing relatively simple osteotomies (i.e., single longitudinal or coronal osteotomy, or simple transverse) due to the previously described difficulties. Our main concern, however, was the difficulty in visualizing the articular reduction. In effect, once the mal–united fragment was reduced (elevated) the narrow radiocarpal space prevented an adequate assessment of the joint congruity without extreme manipulation of the wrist. The surgeon must solely rely on fluoroscopy to assess the reduction, even though fluoroscopy has been shown to be unreliable with regard to evaluating any articular gap or step–off under the best of circumstances.9

Inspired by the experience with laparoscopy, in which carbon dioxide is used in place of fluid—and by the invaluable informal comments by other colleagues who were performing parts of arthroscopic ganglion resection without fluid irrigation (personal communication, doctors Atzei and Luchetti of Italy and doctors Zaidemberg and Perotto of Argentina)—we were inspired to perform wrist arthroscopy without infusing fluid (i.e., the dry technique).10 This proved to be crucial to the execution of the technique described in this chapter. An intra–articular inside–out osteotomy11 of distal radius mal–unions hinges on use of the “dry” arthroscopic technique, which is therefore also presented in detail (along with some technical tips).

Contraindications

There are no absolute contraindications to this technique, provided the cartilage is not worn out.11 We have no experience with osteotomies older than three months. It is possible that the presence of cartilage degeneration or arthrofibrosis might impede the arthroscopic procedure, but we have no data to support or refute this. A loss of articular cartilage would preclude this operation, in which case we would then opt for an osteochondral graft12 or a partial wrist arthrodesis.13,14 We would therefore recommend a diagnostic arthroscopy in cases older than three months prior to proceeding with an osteotomy.

Surgical Technique

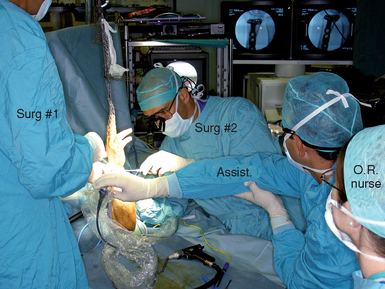

The surgical technique is similar to a standard wrist arthroscopy save that irrigation fluid is not used during the procedure. It is of note, however, that this technique is more cumbersome and complicated than the average wrist arthroscopy. First, it requires an open exposure of the distal radius for plate fixation of the fragments in addition to the arthroscopic–assisted osteotomy. Second, it requires alternating the hand from a suspended position to flat on the operating table. Third, fluoroscopy is used periodically during the procedure—which is facilitated by placing the hand flat. The osteotomes and probes used need to be sturdier than the average arthroscopic instruments (Figure 18.1).

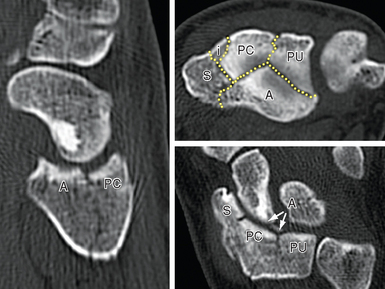

Finally, the assistance of another experienced surgeon is integral to the procedure (Figure 18.2). It is important that everyone on the surgical team be prepared and familiar with their assigned role in order to minimize operating time. It is helpful for the surgeon to preplan the osteotomies beforehand based on a review of the preoperative X–rays and if possible of the original fracture films. The author has found a good–quality preoperative CT scan to be invaluable, since the intraoperative view of the joint can be quite confusing due to the disruption (Figure 18.3).

The hand is then placed on traction from a bow with a custom–made system that allows one to easily change the hand from a horizontal to a vertical position while maintaining a sterile field.11 The standard 3−/,4 and 6–R portals are developed. Transverse 1–cm skin incisions are preferred on the dorsum of the wrist because they heal with a minimal scar. To avoid lacerating any nerve or tendon, a superficial skin incision is made with a #15 blade. A hemostat is used to widen the portal to permit the smooth entrance of the osteotomes and other necessary instruments (Figure 18.1). Apart from dorsal portals, a volar radial (VR) portal is always used. If a Henry incision is planned, the portal is developed as recommended by Levy and Glickel.15 Otherwise, we follow the technique of Doi et al. or of Slutsky16,17 (Figure 18.4). The quality of the articular cartilage over the adjacent scaphoid and lunate is assessed along with exploration of the midcarpal joint if there is any doubt as to the integrity of the interosseous ligaments.

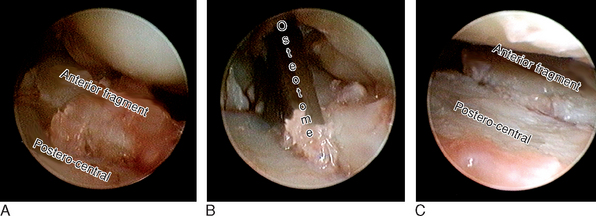

Often, scar and new bone formation between the fragments impede reduction. This early granulation tissue should be resected with the help of small curettes or burs introduced through the portals. Once the reduction is acceptable (Figure 18.5), one surgeon maintains the position of the fragments while the assistant inserts the distal locking pegs in the plate. This step may be difficult because the flexor carpi radialis (FCR) and digital flexors are under tension (due to the traction) and impede insertion of any ulnar screws in the plate. This step is facilitated by backing off the wrist traction sufficiently to allow tendon retraction by insertion of a Farabeuf retractor. A compromise must be made in order to prevent a complete collapse of the radiocarpal space.

FIGURE 18.5 Correction of a step-off in the patient shown in Figure 18.2. In the right wrist, the arthroscope is in 6-R (at the very far upper left corner is the styloid). (A) Step-off on the scaphoid fossa. (B) The osteotome (entering the joint through the volo-radial portal) is separating the mal-united fragments. (C) Corresponding view after reduction.

(From Piñal F, et al. Dry arthroscopy of the wrist: surgical technique. J Hand Surg 2007;32A:119–23.)

The hand is again suspended under traction for a final inspection of the articular surface. The joint is then irrigated with 10 to 30 cc of saline introduced through the scope’s side tube, and a shaver is used to remove all debris. Fluoroscopy can be used repeatedly throughout the procedure by releasing the hand from the traction bow.11 Some authors find it easier to perform wrist arthroscopy with the hand lying flat on the table, but we have no experience with this technique.18

Practical Tips

From a practical point of view, the lack of extravasated fluid allows one to easily define the tissue planes during an open approach to the distal radius. One disadvantage is the learning curve that comes with mastering any new technique. A frequent frustration of the dry technique is the frequent loss of vision from blood or soft–tissue splashes. Valuable time is lost by removing the scope for cleaning each time this occurs. There are several tricks to maintaining visual access that should be kept in mind.10,11

Results

The technique presented in this paper is drawn from experience in four patients with nascent intra–articular mal–unions of relatively short duration (five weeks to three months), with a follow–up of 18 days to 6 months. Two patients had a single fragment mobilized (one anteromedial fragment, one styloid fragment). The other two patients had two or more fragments mobilized (both C31 fractures of the AO classification) (Figures 18.6 and 18.7). Gaps of less than 1 mm were unavoidable after the operation due to a preexisting loss of cartilage and early granulation tissue, but intra–articular steps were reduced to 0 mm (from a maximum of 5 mm).

FIGURE 18.6 Same patient as in Figures 18.2 and 18.3. (A) Preoperative X-ray (depressed fragments highlighted by black dots). (B) Restoration of the articular line (six weeks).

(From Piñal F, et al. Dry arthroscopy of the wrist: surgical technique. J Hand Surg 2007;32A:119–23.)

It may be argued that fragments may be more easily defined early on by simply breaking the external callus. Based on the experience of our group and others, however, impacted cartilage containing fracture fragments is soundly healed by as early as three to four weeks and needs to be redefined with the use of an osteotome.19,20 Piecemeal fragmentation can occur if the mobilization is not done carefully. Herein lies the advantage of the procedure. The arthroscope allows us to follow the exact line of chondral fracture under magnification, and to restore the anatomy of the cartilaginous surface.

Acknowledgments

Gratitude goes to Mr. Robert Jenkins for help with the English translation of this chapter.

1 Jupiter JB, Ring D. A comparison of early and late reconstruction of malunited fractures of the distal end of the radius. J Bone Joint Surg. 1996;78A:739-748.

2 Wagner WFJr., Tencer AF, Kiser P, Trumble TE. Effects of intra-articular distal radius depression on wrist joint contact characteristics. J Hand Surg. 1996;21A:554-660.

3 Knirk JL, Jupiter JB. Intra-articular fractures of the distal end of the radius in young adults. J Bone Joint Surg. 1986;68A:647-659.

4 Fernandez DL. Reconstructive procedures for malunion and traumatic arthritis. Orthop Clin North Am. 1993;24:341-363.

5 Trumble TE, Schmitt SR, Vedder NB. Factors affecting functional outcome of displaced intra-articular distal radius fractures. J Hand Surg. 1994;19A:325-340.

6 González del Piño J, Nagy L, González Hernandez E, Bartolome del Valle E. Osteotomías intraarticulares complejas del radio por fractura. Indicaciones y técnica quirúrgica. Revista de Ortopedia y Traumatología. 2000;44:406-417.

7 Thivaios GC, McKee MD. Sliding osteotomy for deformity correction following malunion of volarly displaced distal radial fractures. J Orthop Trauma. 2003;17:326-333.

8 Ring D, Prommersberger KJ, González del Piño J, Capomassi M, Slullitel M, Jupiter JB. Corrective osteotomy for malunited articular fractures of the distal radius. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87:1503-1509.

9 Edwards CCII, Haraszti CJ, McGillivary GR, Gutow AP. Intra-articular distal radius fractures: Arthroscopic assessment of radiographically assisted reduction. J Hand Surg. 2001;26A:1036-1041.

10 Piñal F del, Garcia-Bernal FJ, Pisani D, Regalado J, Ayala H. The dry technique for wrist arthroscopy. J Hand Surg. 2007;32A:119-123.

11 Piñal F del, Garcia-Bernal FJ, Delgado J, Sanmartín M, Regalado J. Correction of malunited intra-articular distal radius fractures with an inside-out osteotomy technique. J Hand Surg. 2006;31A:1029-1034.

12 Piñal F del, García-Bernal JF, Delgado J, Regalado J, Sanmartín M. Reconstruction of the distal radius facet by a free vascularized osteochondral autograft: Anatomic study and report of a case. J Hand Surg. 2005;30A:1200-1210.

13 Saffar P. Radio-lunate arthrodesis for distal radial intraarticular malunion. J Hand Surg. 1996;21B:14-20.

14 Garcia-Elias M, Lluch A, Ferreres A, Papini-Zorli I, Rahimtoola ZO. Treatment of radiocarpal degenerative osteoarthritis by radioscapholunate arthrodesis and distal scaphoidectomy. J Hand Surg. 2005;30A:8-15.

15 Levy HJ, Glickel SZ. Arthroscopic assisted internal fixation of volar intraarticular wrist fractures. Arthroscopy. 1993;9:122-124.

16 Doi K, Hattori Y, Otsuka K, Abe Y, Yamamoto H. Intra-articular fractures of the distal aspect of the radius: Arthroscopically assisted reduction compared with open reduction and internal fixation. J Bone Joint Surg. 1999;81A:1093-1110.

17 Slutsky DJ. Clinical applications of volar portals in wrist arthroscopy. Tech Hand Up Extrem Surg. 2004;8:229-238.

18 Huracek J, Troeger H. Wrist arthroscopy without distraction: A technique to visualise instability of the wrist after a ligamentous tear. J Bone Joint Surg. 2000;82B:1011-1012.

19 Marx RG, Axelrod TS. Intraarticular osteotomy of distal radius malunions. Clin Orthop. 1996;327:152-157.

20 Piñal F del, Garcia-Bernal FJ, Delgado J, Sanmartin M, Regalado J. Results of osteotomy, open reduction, and internal fixation for late-presenting malunited intra-articular fractures of the base of the middle phalanx. J Hand Surg. 2005;30:1039-1050.