CHAPTER 39 Correction of Breast Asymmetry in Teenagers

Summary and Key Points

Introduction

Correction of breast asymmetry in the adolescent girl is a challenging problem, and the treatment alternatives are numerous. The origin of the asymmetry may involve the development of the breast tissue itself, the foundation onto which the breast tissue rests, the invasion of the breast by anomalous lesions, or the deformation of the developing breast by surrounding tissue restriction.1

Indications

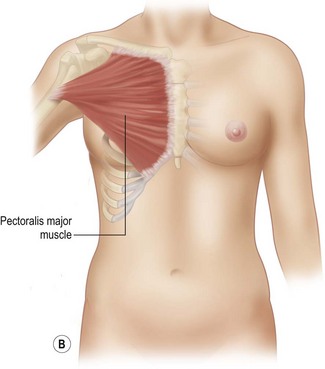

Developmental non-syndromic breast asymmetry may by reflected in either difference in size or difference in shape. Teenagers often present with overdevelopment of one breast and relative hypoplasia of the other, creating a mild to moderate asymmetry. A discussion must be undertaken to decide which breast volume the patient prefers. With mild to moderate asymmetries, it is often easiest to reduce the larger breast. Despite this, perfect symmetry remains a challenge, as only one breast is operated on. Augmentation of the smaller breast creates even more decision possibilities and symmetry challenges. The choice of material with which to augment must be selected: implant versus autologous. A unilateral implant offers an easy solution, but makes upper and lower pole symmetry with the opposite breast difficult, while autologous tissue involves more extensive surgery and donor site morbidity, albeit a more stable long term solution. Either of the latter options may still warrant contralateral breast surgery (i.e. mastopexy, reduction or augmentation) to achieve best symmetry. In the case of severe hypoplasia of the smaller breast, one has no choice but to augment the hypoplastic side, and the same decision making choices apply regarding which material to use. Additionally in this case, the possibility of increasing the skin envelope with prior expansion to obtain better ptosis must be contemplated. The treatment options are pushed yet further in the case of syndromic developmental breast asymmetry such as Poland’s syndrome. In Poland’s syndrome, variable unilateral hypoplasia, potential thoracic rib deformity along with variable absence of the pectoralis major muscle leads to all the above treatment alternatives to which is added a possible muscle transposition to correct the asymmetry (Fig. 39.1).

The thoracic cage is the foundation onto which the breast tissue rests. Asymmetry in the thoracic cage will secondarily translate into asymmetrically appearing breasts (Fig. 39.2). This is often seen in patients with scoliosis.2 Assessment of the scoliosis and resulting chest wall deformity must be recognized and related to the patient so that proper treatment options can be considered.

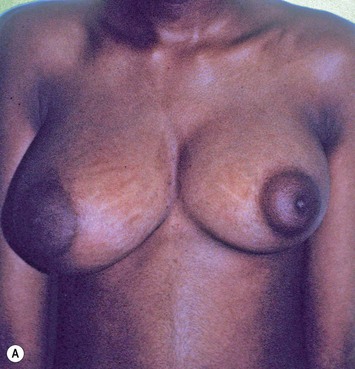

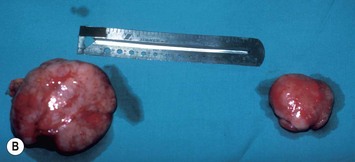

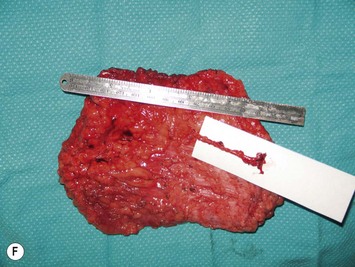

Breast asymmetry secondary to proliferation of anomalous lesions is relatively frequent, and proper examination is necessary to identify these lesions. Benign fibroadenomas are common lesions presenting in breast tissue, unilaterally or bilaterally (Fig. 39.3).3 These tumours are well circumscribed and can usually be removed completely. Preoperative ultrasonography is used to confirm the presence and location of the mass within the breast tissue.

Isolated Breast Asymmetry Reconstruction

With isolated breast asymmetry, multiple options are available depending on the severity of the asymmetry and the patient’s desires.4 With mild to moderate asymmetry one can decide to reduce the larger breast, or augment the smaller one.

Reduction of the larger breast is often the easiest solution if the contralateral breast is of sufficient volume and pleasing to the patient (Fig. 39.4). Despite this, perfect symmetry may still be problematic as only one breast is operated on, and symmetric degree of ptosis is more difficult to achieve. A contralateral mastopexy may help achieve a balanced result (Fig. 39.5).

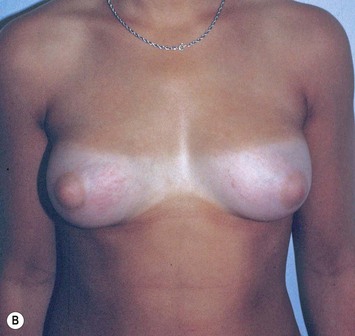

Augmentation of the smaller breast may be the decided option. The use of an implant for augmentation allows for a simple way to augment breast volume and fill out upper and lower poles of the breast (Fig. 39.6). The lack of plasticity of an implant, however, makes it difficult to achieve ideal symmetry in breast shape and contralateral surgery is often indicated (Fig. 39.7). Upper pole fullness and a relative lack of natural ptosis tend to remain with this treatment option. Additionally, the potential for capsular contracture and need to eventual implant replacement in the long term is not negligible, particularly in teenagers.

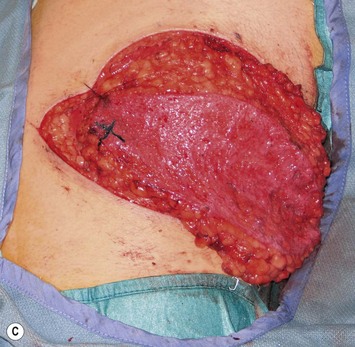

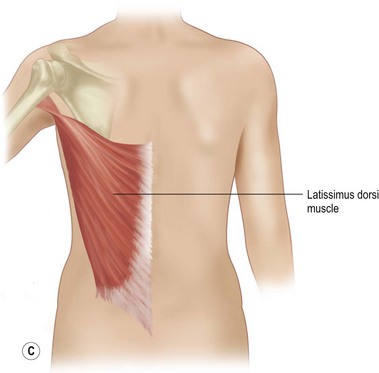

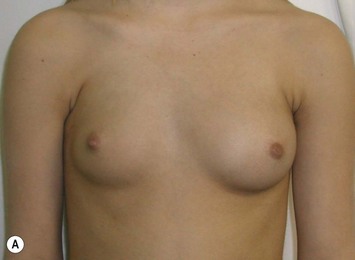

The use of autologous material for augmentation obviates many of the problems that implants pose. The tissue not only responds to physiologic changes of weight gain, ageing, or hormonal variations, but additionally responds to gravitational forces creating a far more natural ptosis mimicking the opposite breast (Figs 39.8 and 39.9). Capsular contracture or other potential surgical procedures are no longer an issue with this treatment option. The choices of autologous tissues are multiple5–7 depending on the amount required and level of surgeon’s expertise. Microsurgical free tissue autologous reconstruction is technically more demanding and creates a donor site with resultant additional scars. The long term benefits, however, are still weighted favourably. The choice of free tissue transfer is dependent on patient physiognomy and surgeon’s experience. The adolescent patient often has little abdominal fat, so that a DIEP is often inadequate in volume. An SGAP or IGAP flap offers enough volume for the most part.5,8 The latter has become our preferred free tissue transfer option as the scar location is most appealing in the North American setting. When a relatively small amount of autologous tissue is required for augmentation, the use of a pedicled latissimus myocutaneous transfer may be a valid option. This circumvents the need for microsurgical technique. This latter option can be combined with a further augmentation procedure, either allogenic or autologous. Having said this, in some patients, even though autogenous reconstruction may seem the best option from the surgeon’s point of view, a prosthetic augmentation can be done early: it is a simpler procedure that does not compromise a later autologous transfer and may help the patient mature a few years.

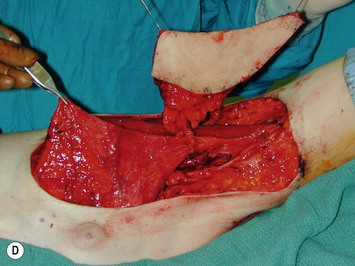

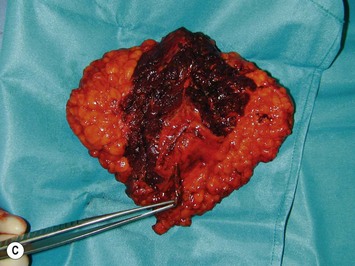

Technical details of the inferior gluteal perforator flap harvest

Mapping of the perforators is done prior to surgery with the patient in lateral decubitus position using a color Doppler to locate the major perforators as they exit the muscular aponeurosis (Fig. 39.10). The crease is marked and the flap is outlined with a major part of the flap located on the buttock itself. The patient is positioned laterally during the surgery to allow two surgical teams to work simultaneously to prepare the thorax and thoracodorsal vessels while harvesting the flap. The dissection is carried out from lateral to medial, incising the lateral and superior edge of the skin and elevating the remaining buttock skin superiorly to augment the amount of fat harvested with the flap and include more perforators if needed. The deep dissection is carried out under the gluteus muscle fascia until perforators of adequate size are located. One large perforator is generally sufficient to provide adequate blood supply to the flap. It is followed through the muscle fibres until the inferior gluteal vessels can be seen in the fibro-fatty layer beyond the gluteus maximus muscle. Lateral perforators seem to have a longer course through the muscle, supplying a longer pedicle. Careful intramuscular dissection without traction on the flap is imperative. The choice of recipient vessel (internal mammary versus thoracodorsal) depends on the local anatomy and scar location. Patients with Poland syndrome will often have had transposition of the subscapular vascular system with the latissimus transfer, requiring anastomosis to the internal mammary despite a more visible scar location. Once anastomosed to the recipient vessels, it is frequent to note that bleeding from the flap is slightly congested initially and does improve within 24–36 hours postoperatively. A flap skin island can be exposed, or buried Doppler probes on the vessels can be used for postoperative monitoring.

Poland Syndrome

With Poland syndrome, there are several elements that need to be reconstructed.9,10 These patients may have multiple deformities in addition to the hypoplasia or aplasia of the breast and/or areola and absence of the pectoralis major muscle. There may be rib abnormalities, other muscle abnormalities (latissimus dorsi, serratus anterior, etc.) and abnormalities of the upper limb such as brachysyndactyly, all of which have to be assessed and addressed. The expression of Poland syndrome is quite variable, and the treatment approaches should be tailored to the individual patient (Fig. 39.11). Regarding the breast asymmetry itself, the same reconstructive principles described above apply. The hypoplasia of the breast is often so severe that prior expansion is necessary. Additionally, the absence of the pectoralis muscle in these patients requires anterior transposition and humeral re-insertion of the latissimus dorsi to create an anterior axillary fold. The expansion and augmentation is done secondarily under the transposed muscle, offering a better muscle–skin envelope. As previously mentioned, when augmentation is done with free autologous tissue in a patient having undergone latissimus dorsi transposition, attention must be given to the recipient anastomosis vessels, as scapular vascular anatomy will most likely have been altered by the transfer. In this case, the internal mammary vessels may be the recipient vessels of choice.

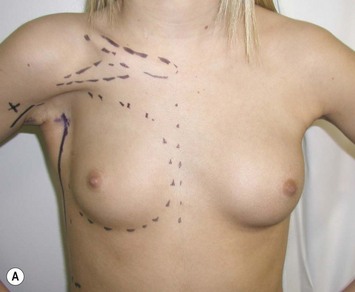

Technical details for latissimus dorsi functional transfer

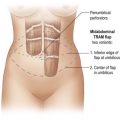

The following technical details are important for the surgeon who is undertaking Poland syndrome correction. Preoperative markings should include the location of the normal inframammary fold, the midline, and the normal pectoralis insertion on the humerus (Fig. 39.12). The latissimus muscle flap is an innervated functional transfer and the tendon needs to be detached and re-inserted on the humerus to form the anterior axillary fold. A short mid-lateral incision is used on the chest to dissect the latissimus and the anterior pocket for muscle insertion. Another 3 cm incision is made on the inner arm to re-attach the tendon with a bone anchor device on the humerus. After the tendon is reinserted, the muscle is sutured superiorly and medially. The latissimus dorsi muscle is larger but thinner than the pectoralis muscle. The muscle can be folded on itself in the upper third to increase the volume in the subclavicular area. The arm is kept adducted for 4–6 weeks postoperatively.

In some patients, the breast volume is adequate and only the latissimus transfer is necessary (Fig. 39.13).

When a small augmentation is needed either an implant or a buried musculocutaneous latissimus dorsi flap can be used. Only a modest size augmentation can be obtained with a buried dorsal skin flap (Fig. 39.14). The buried skin island can be brought directly attached on the muscle (musculocutaneous flap) or can be harvested on a perforator of the thoracodorsal artery (TAP flap) and detached from muscle. This provides more flexibility in the positioning of the functional muscle unit and the buried skin flap. The buried skin island can be placed in the subclavicular area when the breast volume is adequate and the subclavicular area remains deficient even with the latissimus muscle transfer (Fig. 39.15).

When a large volume is needed, expansion under the transposed latissimus dorsi muscle flap is helpful not only to create sufficient space for the augmentation but also to lower the nipple–areola complex. A prosthesis inserted in the expanded pocket can provide adequate symmetry when there is no ptosis of the normal breast. However, progressive ptosis of the normal side may occur and worsen the results years later (Fig. 39.16).

When a free autogenous flap (IGAP or other) is considered (Fig. 39.17), the anastomoses are planned on the internal mammary vessels since the thoracodorsal vessels are already used for the latissimus transfer. The surgeon needs to be prepared for vascular anomalies. Preoperative Doppler may help in assessing the size and location of recipient vessels.

Miscellaneous Breast Anomalies

Juvenile breast hypertrophy (sometimes called ‘virginal’) is a premature exaggerated overgrowth of breast tissue often occurring before the teenage years. This is a dramatic exception to the advice of waiting until growth is completed before envisioning treatment. In these patients breast development can be so rapid that it outgrows its existing blood supply and surgery must be performed sometimes on an urgent basis.11 Continued growth following breast reduction is frequent, and is also reported to occur years later during pregnancy.12 Some authors have recommended subcutaneous mastectomy in order to control an aggressive process. Pharmacologic treatment with tamoxifen has been reported to reduce breast growth but its use is still controversial considering the significant side effects.13 Figure 39.18 illustrates the natural history of the disease with rapid initial growth and further dramatic growth in spite of standard surgical treatment. The opposite breast did not stay static but underwent growth following its own timeline as well.

Beckers’s nevus is a unilateral hyperpigmented, often hairy, cutaneous hamartoma14–16 that can be associated with a significant breast hypoplasia and require surgical correction (Fig. 39.19).

Retractile burn scar may interfere with normal breast development.17–20 Second and third degree burns to the anterior chest are frequent in childhood. Parents should be advised to return for evaluation of the scar in late childhood to assess if breast development may be affected. When a tight scar produces elevation or lower displacement of the nipple–areola complex, it is advisable to release the scar before breast growth. Often, unburned skin can be expanded to provide local transposition flaps that can be inserted to replace part of the scar allowing normal skin distension with breast development (Fig. 39.20).

Vascular anomalies

Massive lymphatic malformations can occur on the chest and axilla. Surgical excision is more or less complete depending on the type of the lesion (macro- or microcystic). The breast tissue may be involved and partially or totally excised or may be displaced as a result of tissue distortion by the malformation. Cutaneous lymphatic fistulas are not uncommon in the axillary region as the patient reaches puberty and are a burden to the patient and a challenge to the surgeon. Creative reconstruction will be necessary to excise residual lesions, replace the skin involved, and provide acceptable breast symmetry (Fig. 39.21).

A rapidly involuting hemangioma is a benign vascular tumour that regresses spontaneously over the first few months of life leaving atrophic subcutaneous tissue and telangectasias. When located on the anterior chest, the residual deficit may include breast hypoplasia. A combination of expansion of the normal adjacent skin to resurface the area and breast reconstruction with a partially buried autogenous buttock flap can provide adequate symmetry (Fig. 39.22).

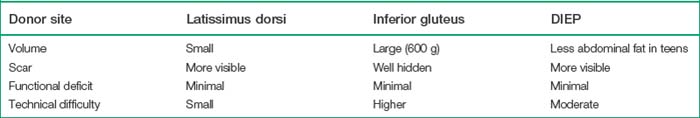

Donor Sites

Although autogenous reconstruction can provide a natural breast with longlasting symmetry, additional scarring and morbidity should be discussed at length.6,8,21 Teenagers have to be well informed since they tend to idealize the surgery expecting a perfect breast and no donor defect. The technical difficulty related to flap harvesting, the duration of the procedure and hospital stay should also be considered. Table 39.1 outlines the advantages and disadvantages of the latissimus, gluteus and abdominal flaps used (Fig. 39.23).

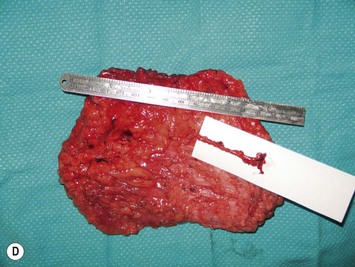

The inferior gluteus flap (Fig. 39.24) can be harvested with a piece of the gluteus muscle as a musculocutaneous flap or as a perforator flap (IGAP). Both flaps are based on the inferior gluteal vessels. The amount of tissue that can be harvested and the location of the scar are similar. However, the residual contour deformity of the musculocutaneous flap is more significant as the muscle normally inserts on the trochanter (Fig. 39.24A, C) compared with the perforator flap (Fig. 39.24B, D). Both donor sites have a slightly diminished projection that can be seen from above (Fig. 39.24E). The vascular pedicle of the perforator flap is significantly longer. The posterior thigh hypoesthesia reported following musculocutaneous flap harvest is minimal with the perforator flap.22

1 Sadove AM, van Aalst JA. Congenital and acquired pediatric breast anomalies: a review of 20 years’ experience. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;115(4):1039-1050.

2 Normelli H, Sevastik JA, Ljung G, Jonsson-Soderstrom AM. The symmetry of the breasts in normal and scoliotic girls. Spine. 1986;11(7):749-752.

3 Park CA, David LR, Argenta LC. Breast asymmetry: presentation of a giant fibroadenoma. Breast J. 2006;12(5):451-461.

4 Argenta LC, VanderKolk C, Friedman RJ, Marks M. Refinements in reconstruction of congenital breast deformities. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1985;76(1):73-82.

5 Granzow JW, Levine JL, Chiu ES, Allen RJ. Breast reconstruction with gluteal artery perforator flaps. J Plast Reconstr Aesth Surg. 2006;59(6):614-621.

6 Tachi M, Yamada A. Choice of flaps for breast reconstruction. Int J Clin Oncol. 2005;10(5):289-297.

7 Paletta CE, Bostwick JIII, Nahai F. The inferior gluteal free flap in breast reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1989;84(6):875-883.

8 Boustred AM, Nahai F. Inferior gluteal free flap breast reconstruction. Clin Plast Surg. 1998;25(2):275-282.

9 Longaker MT, Glat PM, Colen LB, Siebert JW. Reconstruction of breast asymmetry in Poland’s chest-wall deformity using microvascular free flaps. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1997;99(2):429-436.

10 Rintala AE, Nordstrom RE. Treatment of severe developmental asymmetry of the female breast. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg Hand Surg. 1989;23(3):231-235.

11 Griffith JR. Virginal breast hypertrophy. J Adolesc Health Care. 1989;10(5):423-432.

12 Ryan RF, Pernoll ML. Virginal hypertrophy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1985;75(5):737-742.

13 O’Hare PM, Frieden IJ. Virginal breast hypertrophy. Pediatr Dermatol. 2000;17(4):277-281.

14 Angelo C, Grosso MG, Stella P, et al. Becker’s nevus syndrome. Cutis. 2001;68(2):123-124.

15 Rasi A, Taghizadeh A, Yaghmaii B, Setareh-Shenas R. Becker’s nevus with ipsilateral breast hypoplasia: a case report and review of literature. Arch Iran Med. 2006;9(1):68-71.

16 Hoon JJ, Chan KY, Joon PH, Woo CY. Becker’s nevus with ipsilateral breast hypoplasia: improvement with spironolactone. J Dermatol. 2003;30(2):154-156.

17 Comparin JP, Bichet JC, Boulos JP, Oddou L, Foyatier JL. Breast burn sequelae. Classification and therapeutic indications. Ann Chir Plast Esthet. 2001;46(3):227-234.

18 Foley P, Jeeves A, Davey RB, Sparnon AL. Breast burns are not benign: long-term outcomes of burns to the breast in pre-pubertal girls. Burns. 2008;34(3):412-417.

19 Neale HW, Smith GL, Gregory RO, MacMillan BG. Breast reconstruction in the burned adolescent female (an 11-year, 157 patient experience). Plast Reconstr Surg. 1982;70(6):718-724.

20 MacLennan SE, Wells MD, Neale HW. Reconstruction of the burned breast. Clin Plast Surg. 2000;27(1):113-119.

21 Elliott LF. Options for donor sites for autogenous tissue breast reconstruction. Clin Plast Surg. 1994;21(2):177-189.

22 Dupere S, Bergeron L, Bortoluzzi P, Del-Duca T, Caouette-Laberge L. Donor-site morbidity of the inferior gluteal musculocutaneous flap for breast reconstruction in teenagers. Ann Plast Surg. 2007;59(6):617-620.