Coordination

What is coordination?

Successful movement involves the complex coordination of multiple joints and muscles which is achieved via the appropriate sequencing, timing and grading of muscle recruitment (Shumway-Cook and Woollacott 2007; Berthier et al. 2005). Even a simple reaching task involves all levels of the central and peripheral nervous system with the integration of these sensorimotor systems occurring primarily in the cerebellum (S2.12) (Fuller 2004). Smooth accurate movement involves the interaction of hand–eye coordination, inter-limb and trunk coordination.

Incoordinated movement

• Sensory feedback: Proprioception (S2.23) or vision (S2.10 and S3.27)

• Motor output: Altered muscle tone (S3.21) or muscle weakness (S3.30).

Ataxia

Ataxia is a term used to describe the motor incoordination presented by patients with a deficit affecting the cerebellum (S2.12) during voluntary movement. It includes symptoms such as nystagmus, reduced manual dexterity, poor balance and altered gait (Bakker et al. 2006; Ilg et al. 2008), dysarthria and dysmetria (Thoma et al. 2008). Dysmetria, is a problem with judging the distance of movement and is often referred to as intention tremor. The outcome is inaccurate movement with overshooting (hypermetria) and undershooting (hypometria) during the task. Ataxia can affect the trunk (trunk ataxia) or limbs (limb ataxia) or both, depending on whether the lesion is in midline or the cerebellar hemispheres, respectively. The incoordinated movement that is produced affects mobility, when the patient presents with a drunken swaggering gait and all other functional activities. Ataxic movement is thought to occur due to impairment in the timing and duration of muscle activation, or the magnitude and grading of force production (Ausim 2007).

How do I assess coordination?

Observation of functional tasks

Assessment of coordination usually begins by observing the patient’s ability to perform simple functional tasks (S3.18) taking note of the accuracy, speed and trajectory of movement.

The activities observed should challenge both the limbs and trunk. To identify a trunk deficit in isolation, the patient could be requested to sit unsupported with upper limbs held in a static position away from the body. Excessive movement of the trunk could indicate incoordination. However, the therapist should be mindful that there is a great deal of overlap between the concepts of trunk coordination, trunk stability (S3.25) and balance (S3.32). The therapist should also be aware that any problems with trunk coordination will also affect the accuracy of limb movements.

Simple tests of limb coordination

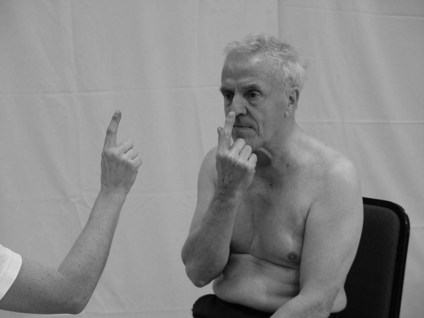

Finger-to-nose test

Therapist

1. The therapist sits in front of the patient, facing them.

2. The therapist holds their finger in front of the patient at eye level (approx. arms length from the patient).

3. With eyes open the patient is asked to touch their own nose with their index finger and then touch the therapist’s finger (Fig. 26.1).

Figure 26.1 Finger–nose test.

4. This is repeated several times and should be accomplished smoothly and easily.

5. If the performance is accurate, ask the patient to repeat the movement faster.

6. Modify the position of the therapist’s finger and repeat the test, to test different planes of movement.

7. This test can be repeated with eyes closed with the patient only touching their own nose.

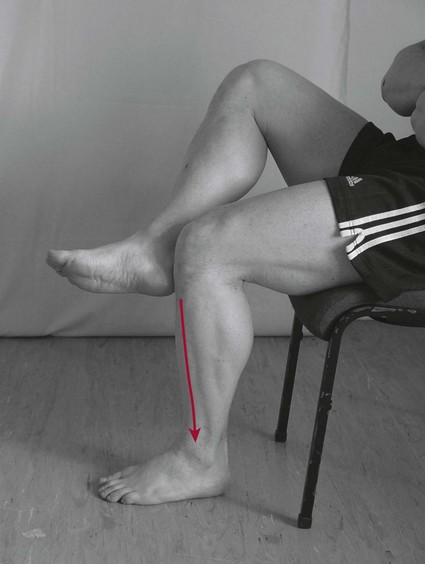

Heel–shin test

Therapist

1. The patient is asked to place the heel of one lower limb to touch the knee of the opposite leg.

2. The patient is requested to run the heel down the shin towards the ankle joint (Fig. 26.2). This should be accomplished smoothly and easily.

Figure 26.2 Heel–shin test.

3. If the performance is accurate this can be repeated several times with increasing speed.

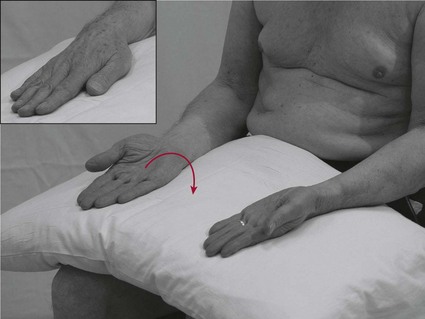

Dysdiadochokinesia

This is the inability to perform rapidly alternating movements.

Therapist

1. The patient should start with one hand rested on their thigh (palm down).

2. They are then asked to turn the hand over (palm up) and continue alternating between palm up and down at a reasonable speed (Fig. 26.3).

Figure 26.3 Testing for dysdiadochokinesia.

3. Repeat with the other hand.

4. This test can be modified so that the patient performs the task at 90° shoulder flexion or by alternating different opposing muscle groups around other peripheral joints (e.g. flexion and extension of the knee).

Note: Dysdiadochokinesia is commonly seen as part of ataxia (cerebellar lesion) but is also difficult to achieve for patients with hypertonia and hypotonia (S3.21).

Hand ‘flip’ test (inter-limb coordination)

Therapist

1. The patient starts with left hand palm down on their lap (the stationary hand).

2. The patient is asked to touch the back of the left hand with the anterior aspect of the fingers of the right hand (Fig. 26.4).

Figure 26.4 Hand ‘flip’ test.

3. The left hand is then turned over (palm up) and the patient touches the palm with the posterior aspect of the fingers of the right hand (Fig. 26.4).

4. This is repeated several times as quickly as possible.

Other simple tests

Is there any deviation from the expected smooth accurate movement?

Does the heel fall off the anterior part of the shin?

Is there evidence of hand slapping rather than a touch?

Does the performance deteriorate when the speed is increased?

Does the patient overshoot or undershoot the target? Yes, this is dysmetria.

Does the performance deteriorate significantly with eyes closed? If the original task was accurate this may indicate a deficit of proprioception.

Is there excessive trunk movement during the task? This could indicate trunk involvement. Sit the patient supported and re-test.

Analysis

Testing coordination informs the therapist of the existence of a movement dysfunction but not about its cause. Further investigation using other objective assessment tools (S3.19–34), integrated with knowledge related to the patient’s pathological condition will facilitate analysis of the causal factors.

References and Further Reading

Ausim, AS. And the olive said to the cerebellum: organization and functional significance of the olivo-cerebellar system. Neuroscientist. 2007; 13:616–626.

Bakker, M, Allum, JH, Visser, JE, et al. Postural responses to multidirectional stance perturbations in cerebellar ataxia. Experimental Neurology. 2006; 202:21–35.

Berthier, NE, Rosenstein, MT, Barto, AG. Approximate optimal control as a model for motor learning. Psychological Review. 2005; 112:329–346.

Crawford, JD, Medendorp, WP, Marotta, JJ. Spatial transformations for eye–hand coordination. Journal of Neurophysiology. 2004; 92110–92119.

Fuller, G. Neurological examination made easy, ed 3. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 2004.

Ilg, W, Giese, MA, Gizewski, ER, et al. The influence of focal cerebellar lesions on the control and adaptation of gait. Brain. 2008; 131:2913–2927.

Johansson, RS, Westling, G, Bäckström, A, et al. Eye–hand coordination in object manipulation. Journal of Neuroscience. 2001; 2117:6917–6932.

Schmitz, TJ. Coordination assessment. In O’Sullivan SB, Schmitz TJ, eds.: Physical rehabilitation assessment and treatment, ed 4, Philadelphia: FA Davis, 2001.

Shumway-Cook, A, Woollacott, MH. Motor control translating research into clinical practice, ed 3. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2007.

Thoma, P, Bellebaum, C, Koch, B, et al. The cerebellum is involved in reward-based reversal learning. Cerebellum. 2008; 7:433–443.