CHAPTER 29 Conventional upper and lower blepharoplasty

History

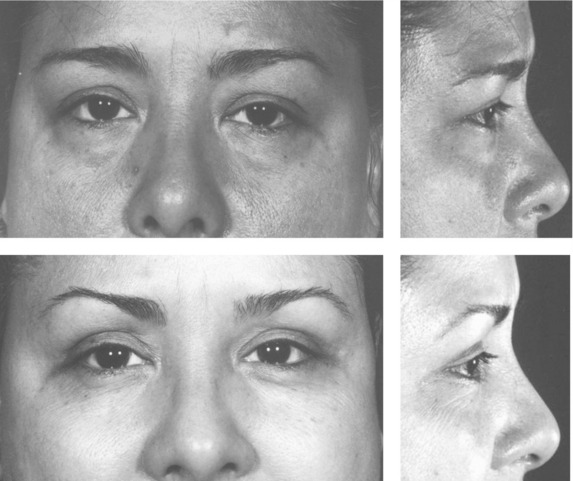

An ever-improving understanding of the dynamic nature of facial anatomy accompanied with a more holistic approach to facial aging has altered the surgical treatment of age-related periorbital changes. Conceptually, trends point towards decreasing tissue removal in favor of tissue rearrangement and repositioning. Standard blepharoplastic incisions now allow for effective treatment of all of the aforementioned age-related changes. Increasingly limited upper eyelid fat excision and minimal lower lid orbicularis occuli violation has helped avoid exacerbation of orbital hollowing and minimized ectropion, respectively. Moreover, precise soft tissue augmentation (autologous and non-autologous) of the upper lid can help recreate a more youthful appearance.1 Similarly, these techniques can be quite useful in blunting the tear trough deformity. Complementing these trends is the use of botulinum toxin (Botox, Allergan) to help decrease rhytids that characterize aging.

Physical examination

Eye exam

A detailed medical and ophthalmologic history and a standard eye exam including visual acuity in each eye is required. Dry eyes, which can be exacerbated by blepharoplasty, are best identified through careful history taking and Schirmer’s testing (less than 10 millimeters of moisture on a piece of filter paper in the conjunctival sac after five minutes is considered abnormal).2 Evaluation includes the assessment of a Bell’s phenomenon which can be protective, particularly if an ectropion develops. Agents which promote bleeding and inhibit clotting must be eliminated and adequate time for reversal of their effects must elapse prior to surgery. Perioperative blood pressure control is vital and should be managed pharmacologically if indicated. A low threshold for ophthalmologic consultation in the event of positive findings on history and physical is advocated.

Excess skin

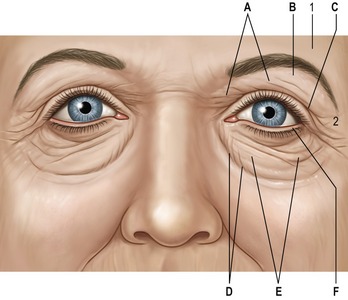

See Fig. 29.1. A common presenting complaint of patients, excess eyelid skin, or dermatochalasis, should be noted on physical evaluation and precisely assessed especially regarding extent and location. Occasionally, the upper eyelid skin redundancy is excessive enough to impact the visual axis and/or result in pseutoptosis. Asymmetry, the correction of which is a central goal of blepharoplasty, must be also identified. Excess skin resulting from blepharochalasis may, ultimately, be treated similarly to age-related skin excess but the risk of ptosis and other disease-specific conditions require recognition of this entity. Lower lid skin excess is less common than lower lid wrinkling which invites a more conservative surgical approach particularly in light of the possibility of ectropion. Pre-tarsal skin fullness is more often due to the underlying orbicularis occuli than to skin excess.

Fat pseudoherniation

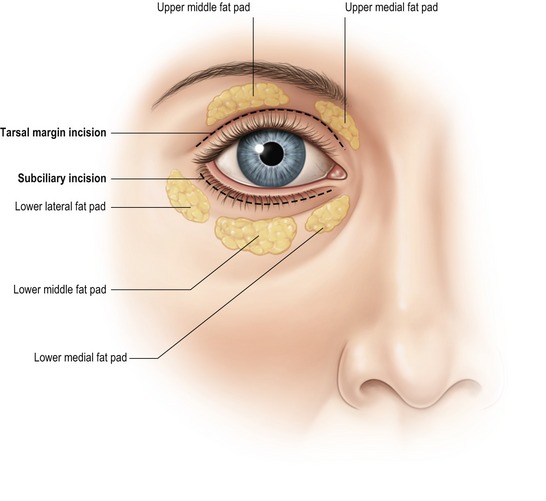

Frequently found in conjunction with skin excess, orbital fat pseudoherniation contributes significantly to the “tired look” of age-related periorbital changes (Fig. 29.2). The size and shape of the medial and middle fat pads of the upper lid and the three lower lid fat pads should be noted. Upward and downward gaze in an upright patient will accentuate the fat pads. The configuration of the lower lateral fat pads, should be documented, since they are easily underappreciated, particularly in the sedated, supine patient.

Technical steps

The patient’s upper lid is marked with a fine-tip, water insoluble marker while sitting upright (Fig. 29.2). It is best to not be misled by the upper lid crease and to place the lower markings along the cephalic border of the tarsal plate thereby setting the stage for the re-establishment of the crease in a more youthful position, albeit not eliminating the need for an aponeurotic procedure if required. Medially, the marking extends to the medial canthus. Laterally, the marking is more variable extending to a point between the lateral canthus and lateral brow as called for by the amount of skin excess and as tolerated by the condition and type of skin. The upper lid mark begins at an acute angle at the medial mark, rises to include skin causing redundancy and asymmetry, continues laterally to address “hooding” and meets the lateral mark in a more obtuse manner. If brow repositioning is planned (transblepharoplastic or otherwise) the brow is stabilized in the new, higher position and the extent of lateral upper lid incisions adjusted accordingly. A smooth Adson’s forceps can pinch the area between markings to assure against over-resection.

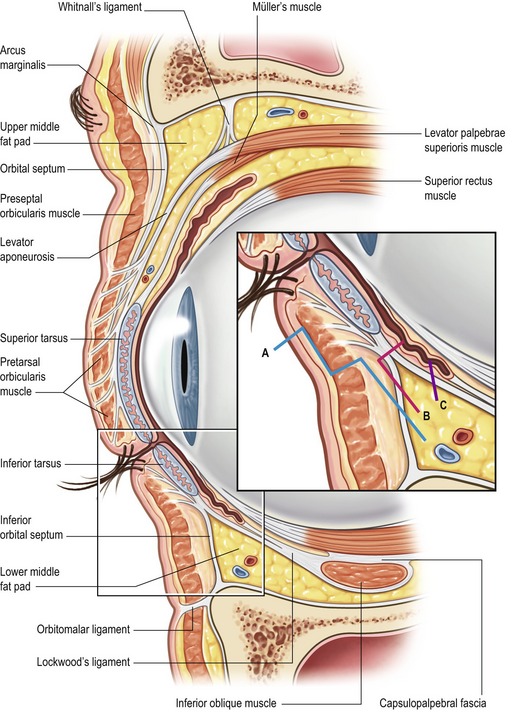

Careful application of corneal protectors is commonly performed by surgeons prior to incision. After moderate subcutaneous infiltration of epinephrine containing local anesthetic, upper lid incisions are carefully performed along the marked lines. Unlike many other areas of the body, once incisions have been made, it can be difficult to correct minor discrepancies. It is the author’s preference to connect the upper and lower incisions at the medial canthus with a single cut with straight Iris scissor, since any skin excess or overlap is more noticeable in this area. A strip of orbicularis oculi is excised towards the lower aspect of the opening, near the cephalic edge of the tarsal strip since this will aid in re-establishment of the upper lid crease at a youthful position. The orbital septum is opened with needle tip cautery or sharp scissors and fat is removed. Medial fat pad visibility on preoperative evaluation can be addressed at this point and the fat, itself, is identified by its whiter color. Generally, resection of the middle fat pad should be conservative and can even be obviated. Upper lid fullness has been recognized as a youthful characteristic and aggressive fat removal may exacerbate orbital hollowing, a hallmark of aging. If needed, correction of ptosis via levator advancement or plication can be performed by the plastic surgeon comfortable with the procedure or by an occuloplastic consultant. Access to the lower lateral fat pad through the upper lid is advocated by some, both for more complete fat pat treatment and for the ability to access the lateral retinacular structures and perform a lid tightening procedure.4 The upper lid incision also allows for ample access for adjunctive brow procedures (medial brow: corrugator resection,5 lateral brow: internal browpexy6) (Fig. 29.3). Both lids are treated prior to closure to allow for the evaluation and treatment of bleeding and closure should be delayed if a canthal procedure is planned. Closure is performed with fine gauge removable suture either in a running or interrupted fashion or a combination thereof. Interrupted closure allows for the correction of significant length discrepancies between upper and lower incisions and my help optimize alignment of the thicker cephalic incision skin with the thinner caudal skin. Narrow Steri-strips are then applied in a fashion to avoid difficulty in opening the eyes.

Strategies for rejuvenation of the lower lids have become increasingly varied. It is the author’s preference to address fat herniation separately from the skin in an effort to minimize ectropion. A transconjunctival “no touch” technique is performed in which the orbicularis oculi is untouched and the septum is minimally violated (Fig. 29.4). After moderate infiltration of epinephrine containing local anesthetic, the lower conjunctiva is opened followed by the capsulopalpebral fascia either with needle tip cautery or sharp scissors allowing for “post-septal” access to the fat pads. A high conjunctival incision above the line of fusion of the septum and capsulopalpebral fascial is appropriate for the preseptal approach, similar to that used for orbital floor fractures, but care should be taken to avoid disruption of the orbicularis. This approach is favored when arcus marginalis release and fat repositioning instead of resection is planned.7 Although a wide incision allows for access to all three fat pads, the medial and middle pads can be accessed through one small medial incision and the lateral fat pad though a small lateral incision. Maintaining a theme of this chapter, fat excision should be conservative and should be guided by the preoperative assessment and intraoperative reference to photographs. Care should be taken to adequately treat the lateral fat pad since it commonly persists postoperatively. The transconjunctival approach also provides access for midfacial procedures. Lower lid skin can be removed as a skin or skin-muscle flap. It is the author’s preference to occasionally treat the lower lid skin surgically, though a subciliary “pinch” of two millimeters of skin. If a canthopexy inadequately addresses lower lid laxity, then a formal lid shortening procedure should be performed. Closure of the conjunctiva is not necessary and, if incised, the skin can be closed with a small gauge silk baseball stitch. Mild to moderate lower lid skin excess and wrinkling can very often be adequately addressed with resurfacing techniques including chemical peels or laser treatment.

Botulinum toxin (Botox) with or without dermal filler injection provides excellent treatment for most glabellar creases and crow’s feet. Although not well-understood anatomically, the tear trough appears to be best effaced with filler injection or fat transfer.

Complications

Although serious complications are unusual, retrobulbar hematoma is a potentially devastating complication that can lead to blindness. Meticulous hemostasis and blood pressure control can help minimize the occurrence of this complication, which usually occurs within the first few hours postoperatively. The hallmark of this complication is considerable pain, a symptom not typically associated with blepharoplasty. Prompt recognition and surgical intervention (suture release and lateral canthotomy) may be sight saving. Adjunctive measures include early ophthalmologic consultation and pharmacologic therapy (acetazolamide, mannitol, and corticosteroids).

Criticisms/downsides

Pearls & pitfalls

Pearls

• Consider the entire periorbita when evaluating a patient for blepharoplasty.

• Consider non-surgical adjuncts (fillers, resurfacing agents, Botox) to complement surgical result.

• Control blood pressure and anxiety closely perioperatively.

• Refer to medical photographs intraoperatively to guide fat pad resection.

• Internal browpexy is a useful method of correcting mild to moderate lateral brow ptosis.

Summary of steps

1. Prepare a detailed, customized written plan and hang it in the operating room with photographs of the patient.

2. Mark the patient in the upright position with a fine tip permanent marker. Manually block or reposition the brow, depending on the operative plan, while performing markings.

3. Upper lid markings extend from just above the medial canthus to just above the lateral canthus or beyond if the patient is light skinned, has a large amount of skin excess, and has preexistent skin creases. The lower mark is at the tarsal plate border while the upper mark forms a gentle arc to encompass the skin excess. With the patient’s eyes closed, a smooth forceps pinch of the planned skin resection can help ensure against over-resection.

4. Lower lid markings, if skin excision is planned, follow the lower lid skin crease and extend from just below the medial canthus to an area below and lateral to the lateral canthus. Care is taken to maintain a distance of at least 8 mm between the lateral upper and lower lid markings.

5. Glabellar rhytids and the tear trough are marked if intervention is planned.

6. The patient undergoes sedation or general anesthesia and a conservative amount of epinephrine containing local anesthetic is injected into the upper eyelids. While the patient is prepped, draped, and corneal protectors are placed, ten minutes is allowed to elapse for the epinephrine to take effect.

7. A skin incision is made along the lower and upper markings with a #15 blade knife in a direction away from the medial markings with careful tension on the skin to ensure clean, non-beveled cuts. The medial junction is not incised at this point. The skin is removed with a knife and the unincised medial junction is smoothly divided with a straight iris scissors.

8. A strip of orbicularis occuli muscle in the planned location of the reformed eyelid crease is excised with curved Steven’s scissors. Care is taken to avoid injury to the underlying lid retractor mechanism, particularly in preoperative cases. The identical procedure is now performed on the other eyelid while a small absorbent dressing is placed on the operated eye.

9. If fat excision is planned, a small amount of epinephrine containing anesthetic is infiltrated deep to the septum if the patient is not under general anesthesia. Needle tip electrocautery on a low setting allows for elevation of the superior orbicularis and access to the orbital septum. A small hole is made in the medial third of the septum and a fine hemostat is used to gently dissect the medial fat pocket which is then conservatively resected with electrocautery. Often the fat is encapsulated by adhesions reminiscent of a chronic supraumbilical hernia sac and division of these adhesions by electocautery while gently teasing the fat will result in sudden exposure of a large amount of fat; the urge to remove all the fat should be resisted. The medial fat pad is accessed and treated similarly. Rarely, a ptotic lacrimal gland can be supported with suture to the inside orbital rim. Access to the lower lateral fat pad can be obtained through the lateral upper lid, particularly when a canthal tightening procedure is planned.

10. If indicated, the post-orbicular plane is followed medially for corrugator supercilii resection and/or laterally for internal browpexy.

11. The pretarsal lid skin is closed with running small gauge nylon suture in a subcuticular fashion. Attention is taken to avoid any bunching of the most medial aspect of the closure. The upper and lower lid skin must be precisely matched since the upper skin is slightly thicker than the lower. The lateral skin is closed with two or three interrupted nylon sutures to work out any skin length discrepancies. If a canthal tightening procedure is planned, the upper lid is closed after the procedure.

12. The lower lid margin is everted with eyelid hooks and a transconjunctival incision is made medially and a few millimeters above the fornix. Gentle dissection, with electrocautery and a hemostat, proceeds through the capsulopalpebral fascia and into the middle orbital fat pocket from which an appropriate amount of fat is removed. Through the same incision, attention is turned to the medial fat pocket which is treated similarly. A separate lateral incision allows for identification of the lateral fat pad which is also treated similarly. The lateral incision allows for access to and treatment of the lateral canthal mechanism, should such a procedure be indicated.

13. If an arcus marginalis procedure is planned, the preseptal approach is employed and the orbital fat is redraped underneath the tear trough and secured percutaneously.

14. If lower lid skin excision is planned, a “pinch” of subciliary skin defined by squeezing a few millimeters of skin with a smooth Adson’s forceps is excised separately. In the event that more skin excision is required, an elongated lateral stab incision is made and followed by a subcutaneous skin flap elevation and redraping at the subciliary level. The incisions are closed with a fine gauge “baseball stitch” of silk suture.

1. Finn JC, Cox S. Fillers in the periorbital complex. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am. 2007;15(1):123–132. viii

2. Jelks GW, McCord CD, Jr. Dry eye syndrome and other tear film abnormalities. Clin Plast Surg. 1981;8(4):803–810.

3. Jelks GW, Jelks EB. Preoperative evaluation of the blepharoplasty patient. Bypassing the pitfalls. Clin Plast Surg. 1993;20(2):213–223. discussion p. 224

4. Glat PM, Jelks GW, Jelks EB, et al. Evolution of the lateral canthoplasty: Techniques and indications. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1997;100(6):1396–1405. discussion pp. 1406–1408

5. Knize DM. Transpalpebral approach to the corrugator supercilii and procerus muscles. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1995;95(1):52–60. discussion pp. 61–62

6. Niechajev I. Transpalpebral browpexy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;113(7):2172–2180. discussion p. 2181

7. Hamra ST. The role of the septal reset in creating a youthful eyelid–cheek complex in facial rejuvenation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;113(7):2124–2141. discussion pp. 2142–2144