Chapter 4 Contraception: Counseling Principles

TACTICS

Patient Education

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Emergency contraception. ACOG Practice Bulletin 69. Washington, DC: ACOG, 2005.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Use of hormonal contraception in women with coexisting medical conditions. ACOG Practice Bulletin 73. Washington, DC: ACOG, 2006.

Benagiano G, Bastianelli C, Farris M. Contraception today. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2006;1092:1.

Deligeoroglou E, Christopoulos P, Creatsas G. Contraception in adolescence. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2006;1092:78.

Draper BH, Morroni C, Hoffman M, et al. Depot medroxyprogesterone versus norethisterone oenanthate for long-acting progestogenic contraception. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006:3. CD005214.

Glasier A, Gulmezoglu AM, Schmid GP, et al. Sexual and reproductive health: A matter of life and death. Lancet. 2006;368:1595.

Hansen LB, Saseen JJ, Teal SB. Levonorgestrel-only dosing strategies for emergency contraception. Pharmacotherapy. 2007;27:278.

Kulier R, Helmerhorst FM, O’Brien P, et al. Copper containing, framed intra-uterine devices for contraception. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 3, 2006. CD005347

Lesnewski R, Prine L. Initiating hormonal contraception. Am Fam Physician. 2006;74:105.

Masimasi N, Sivanandy MS, Thacker HL. Update on hormonal contraception. Cleve Clin J Med. 2007;74:186. 188, 193 passim. Review

McNamee K. The vaginal ring and transdermal patch: New methods of contraception. Sex Health. 2006;3:135.

Nelson AL. Reversible female contraception: current options and new developments. Expert Rev Med Devices. 2007;4:241.

Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Hormonal contraception: recent advances and controversies. Fertil Steril. 2006;86(5 Suppl):S229.

Smith RP. Gynecology in Primary Care. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins, 1997;209.

Szarewski A. Hormonal contraception: Recent advances. J Fam Health Care. 2006;16:35.

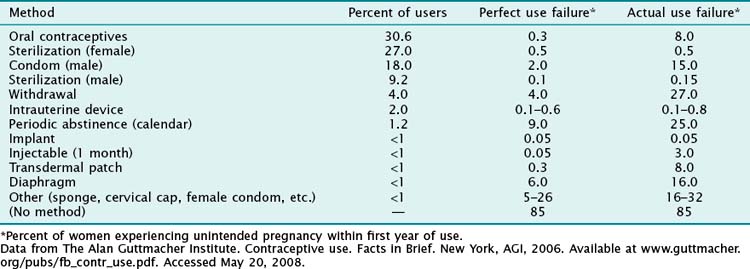

The Alan Guttmacher Institute. Contraceptive use. Facts in Brief. New York: AGI, 2006.