Chapter contents

1.1 Contextualising the learning environment 1

1.2 Addressing misconceptions 2

1.3 Why is a reliable system of pulse taking important? The evidence 3

1.4 Ongoing practice 4

1.1. Contextualising the learning environment

Pulse diagnosis knowledge and its teaching is sometimes written about in nostalgic terms when referring to the traditional methods of learning Chinese medicine (CM) within the master — apprentice system. In this system a student would indenture themselves to a practitioner in exchange for learning CM. This has been termed a ‘craft’ method of learning, not dissimilar to the European craft system or apprenticeship model (Higgs & Edwards 1999, Swart et al 2005):

Apprentices learn in the workplace setting, by studying the ‘master’s art’, from simple, highly supervised tasks to more complex and independent tasks, until they become independent practitioners and finally masters themselves. The focus of the apprenticeship system was on the practical knowledge, craft and art of the practice role of a health care worker. At its best, this model offered individual tuition, direct demonstration and supervision at the hands of an expert role model. At worst, this process incorporated poor role models, limited quality control, limited knowledge of the field and lack of foundation in relevant biomedical, clinical and human sciences

Traditional apprentice systems also have a tendency to focus on traditions to the exclusion of new innovations. Knowledge associated with the rapid and ongoing development in both CM and biomedical fields of health may additionally be excluded from such systems of training. Thus, as a sole model of education, it is probably unsuitable for providing the basic foundational training required of CM practitioners in the modern context. This is because the contemporary or modern practitioner requires knowledge attained from the biomedical system, in addition to the CM system, in order to practice within an increasingly regulated environment. Such knowledge and regulatory requirements for individuals entering the CM profession today render the traditional apprenticeship model of training as either an adjunct to structured degree courses, or suitable for neophyte practitioners as a postgraduate study stream.

Within the modern context of CM education, most practitioners receive their foundational training from attending structured tertiary courses rather than the craft or apprenticeship system. There are a number of reasons for this. Primarily, there are relatively large numbers of individuals entering the profession with too few established practitioners willing to participate in the training of neophyte practitioners. For example, the British Medical Association noted a 36% increase in acupuncture practitioners and a 51% increase in allied health practitioners using acupuncture from 1998 to the year 2000 (BMA 2000). Such an increase in practitioner numbers within a short time frame could never have been catered for by established CM practitioners using traditional apprenticeship training methods (assuming that the ‘new’ practitioners were all appropriately trained).

Courses have been created to meet the demand for CM education in many countries, with sound programs structured to produce competent CM health professionals. In some educational sectors, this has meant developing courses and course content to meet specific criteria developed by regulatory or accreditation bodies. For example, the Australian state of Victoria has a Chinese Medicine Registration Board that requires benchmarks in knowledge and associated skills to be met by graduates from university and other tertiary programs in acupuncture and CM in that state in order to practise in that state. The process for developing such courses is not solely driven by educators but is often in response to CM industry directives. For example, a joint working party representing educators and industry bodies developed guidelines for education of primary CM practitioners in Australia, making reference to similar documentation prepared by the World Health Organization (NASC 2001, WHO 1999). In the US the Acupuncture Examining Committee and the National Commission for the Certification of Acupuncturists (NCCA) set industry entry exam requirements for those wishing to be licensed to practice (BMA 2000). Other countries have set minimum competency benchmarks for the safe and knowledgeable practice of acupuncture, such as New Zealand’s National Diploma of Acupuncture. In addition to educational requirements, many countries are moving to a regulatory model for the practice of CM and acupuncture on concerns of potential risks of harm to patient health and safety.

Accordingly, this book addresses knowledge and skill guidelines for developing a solid foundation in pulse diagnosis. It is as relevant for those from a range of training methods as it is for those from academia. It is a flexible modulated guide to pulse diagnosis and is relevant to regulatory requirements for CM education in pulse diagnosis. It is also an appropriate basis for further learning in other systems of pulse diagnosis such as the family lineage teachings or for further study of other complex systems of pulse diagnosis such as described in the Mai Jing(Wang, Yang (trans) 1997).

1.2. Addressing misconceptions

A misconception about the use of pulse diagnosis is that it was never intended to be used as the sole method of diagnosis. Ideally, the pulse should be appropriately used in conjunction with other diagnostic practices and this was detailed in several classic literature sources. Yet other classical texts such as the Nan Jing clearly emphasised the opposite, noting within its opening chapter that the pulse can be used as the sole diagnostic technique. However, scepticism about such a claim led many commentators over subsequent centuries to question the validity of this claim, warning of the dangers of relying upon a single diagnostic process. The dissent between historical literature sources sets the scene for the perceived usefulness of pulse diagnosis within contemporary practice. While pulse contributes unique information to the clinical diagnostic process, other diagnostic techniques complement this information. Sometimes, pulse diagnosis is not the most suitable diagnostic or most appropriate means of investigation. For example, assessment of the pulse of a patient presenting with an acute sprained ankle would arguably offer little information regarding the extent of the injury sustained to the ligaments. Similarly, Clavey (2003) notes diagnosis should not be dependent solely on the use of pulse for identifying damp/phlegm conditions (p. 296). A systemic condition of damp may not always manifest a damp pulse due to other underlying factors and variables that are present. It is telling that the classical texts on pulse such as the Mai Jing also contain information on using pulse diagnosis with other assessment methods. A motivated, highly trained practitioner uses pulse diagnosis as part of the diagnostic process, and when it is appropriate, but does not always diagnose exclusively by it.

Lay and less experienced practitioners may complicate pulse taking by attributing a mystique to pulse palpation, enshrouding the technique in deliberate obscurity. The notion that pulse diagnosis in the hands of an expert practitioner is unparalleled in the diagnosis of illness, in some literature sources, does nothing to discourage such associations. Veith, in translating the Nei Jing highlights the emphasis placed on pulse diagnosis in that ‘all other methods of determining disease are only subsidiary to palpation and used mainly in connection with it’ (p. 42)

Hence it is said: Those who wish to know the inner body feel the pulse and have thus the fundamentals for diagnosis. Those who wish to know the exterior of the body observe death and birth. Of the six (the pulse and the five colors) the feeling of the pulse is the most important medium of diagnosis

The Veith translation, first published in 1965, was the first widely available translation of any classical CM text in English. Considering the dearth of information on the practice of CM at the time, and China’s closed-door policy, it was widely read and the contents of the book soon integrated into teaching curriculum. Clearly, the Veith translation of the Nei Jing soon gripped the imagination of the neophyte professional group emerging in non-Asian countries at this time. Combined with concepts of Eastern spiritualism and the unique nature of acupuncture as the flagship technique that espoused CM, it was not inconceivable for this diagnostic technique to be soon valued over the other methods of clinical examinations by some practitioners. Ironically, in spite of the distinct dichotomy that some proponents of CM pursue between the biomedical and CM systems of health, this view of pulse diagnosis was not dissimilar to that held by practitioners of Western medicine throughout the early modern period and into the late nineteenth century.

In spite of the publishing and refinement of pulse theory over time, theories that have been shown to have little application within the CM framework for over 1000 years continue to be reiterated as the practice of CM has moved beyond its original cultural, demographical and environmental location. Whether through reiteration of previous pulse literature or derived from clinicians’ need or desire to conform to traditional theoretical constructs even though they have had little basis in the diagnosis or treatment of illness, such information has been retained in the pulse diagnostic framework. Here research is required to illuminate clinically useful information on pulse diagnosis from clinically irrelevant information. However, research and ready enquiry of the pulse assumptions and theories should be tempered with respect for a body of accumulated learning and knowledge acquired through clinical observation and empirical practice: just because something is old doesn’t mean it is outdated. It would be folly to disregard valid empirical knowledge. Conversely, however, because something is simply old doesn’t mean it is necessarily clinically useful. A balance needs to attained — the grain sorted from the chaff.

In this context, this book seeks to address some misconceptions about pulse, and its practice within CM, through examination of the available literature and evidence. The book also seeks to provide a clear guide to the practical use of pulse assessment and diagnostic techniques. To this end, we have attempted to use unambiguous terms, define obscure concepts as we use them and provide instruction on pulse diagnosis as a component of the diagnosis approach for best practice outcomes. This book seeks to promote critical appraisal skills useful in differentiating clinically relevant knowledge from non-clinically relevant claims within the literature.

1.3. Why is a reliable system of pulse taking important? The evidence

Although the historical importance of pulse palpation and its crucial role in the diagnostic process continues to be reiterated in many contemporary CM texts, the underlying assumptions and concepts that underpin pulse as a clinically useful technique have not been substantiated in studies that have used reliable research methods. The paucity of evidence means that long-held and untested assumptions are taken as clinical fact even though no independent evidence has been gathered to either support or refute their validity. For example:

• Are there differences in the pulse characteristics between the three radial arterial pulse positions Cun, Guan, and Chi?

• Are practitioners capable of discerning the minute features of quality that are said to be present in the arterial pulses?

• Can practitioners reliably discern these changes and agree with each other in their interpretation of the pulse?

It is the last of these questions that most notably impacts on the legitimacy of pulse palpation as a valid examination technique. Reliability is important in establishing whether the findings are valid, and for purposes of communication. That is, is the practitioner interpreting changes in the pulse validly as representing a particular disease? Is the practitioner consistently reliable in measuring these changes? For any examination technique, establishing that there are high levels of inter-rater reliability underpins the usefulness of the approach. In relation to pulse diagnosis, this takes on extra importance because of the inherent subjectivity of pulse taking.

In light of the subjective nature of pulse diagnosis, Dharmananda (2000) in his essay on the modern practice of pulse diagnosis claims that there is always the danger of practitioners ‘fantasising’ that the pulse being felt is providing diagnostically valuable information. That is, reading or interpreting something in the pulse when in actual fact there is nothing there. Conversely, and equally dangerous, the practitioner may fail to recognise the presentation of a diagnostically distinct pulse quality or a change in a particular aspect of the pulse which should be used for diagnosis. Both situations may occur from either poor education or poor observational skills. It is also common for experienced practitioners to disregard pulse findings simply because these did not correlate with findings from the other methods of diagnosis. In all situations, diagnoses and hence appropriate treatment may be compromised and practice will consequently suffer.

Because of the subjective nature of pulse assessment using manual techniques this book proposes the ‘pulse parameter’ system of pulse identification that has been previously shown to have reliability yet retains relevance within the CM diagnostic framework.

1.4. Ongoing practice

Although modern practice has doubtlessly been improved by the introduction of new aids, it seems certain that the average physician’s ability to feel and to interpret the pulse has declined

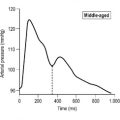

It is anticipated that the information presented in this book will assist in reversing this trend. To understand any field of medicine one needs to understand its composite parts and the relationship of each to the examination process. Pulse palpation in CM contributes to this process. In CM pulse diagnosis sits within the four examination categories as part of the palpation rubric. The other categories are questioning, listening and observation. Each, including pulse diagnosis, has its strengths and weakness. Some are more appropriate to use for different conditions, situations or with different patients, yet each contributes information for arriving at a diagnosis or understanding of the individual’s condition. Too often however, the practitioner may favour one approach over another or set greater store on one technique above all else. Pulse diagnosis is too often viewed in such a fashion. It is eschewed by some for its subjectivity, yet favoured by others as being the technique with almost mystical properties. Little has been written on the practical application of this technique, and less is recorded on the intricate system of haemodynamics that is the pulse. To truly appreciate and understand pulse diagnosis one needs to understand the vessels, the blood, pressure waves and flow waves and the interaction of these in the presence of illness and health. In this book we will examine in detail what the ancient Chinese practitioner termed the mài, the ‘vessels’ or ‘pulse’ and explore the anatomical basis of the arterial system and the complex formation that is the pulse. Biomedical knowledge contributes to our understanding of pulse and will be included when relevant in tandem with information from the CM pulse literature. Together they will provide a firm foundation for the reliable and ongoing practice of pulse diagnosis.

References

BMA, Acupuncture: efficacy, safety and practice. British Medical Association report. (2000) Harwood Academic Publishers, London .

S Clavey, Fluid physiology and pathology in traditional Chinese medicine. 2nd edn. (2003) Churchill Livingstone, Edinburgh .

S Dharmananda, The significance of traditional pulse diagnosis in the modern practice of Chinese medicine. (2000) Institute for Traditional Medicine, Portland, OR ; Online Available: <http://www.itmonline.org/arts/pulse>.

J Higgs, H Edwards, Educating beginning practitioners: challenges for health professional education. (1999) Butterworth Heinemann, Oxford .

NASC, National Academic Standards Committee for Traditional Chinese Medicine. The Australian guidelines for traditional Chinese medicine education. (2001) AACMA, Brisbane .

M O’Rourke, R Kelly, A Avolio, The arterial pulse. (1992) Lea & Febiger, Philadelphia .

V Scheid, Chinese medicine in contemporary China. (2002) Duke University Press, London .

J Swart, C Mann, S Brown, et al., Human resource development. (2005) Butterworth Heinemann, Oxford .

P Unschuld, Nan-Ching: the classic of difficult issues. (1986) University of California Press, Berkeley ; (translator).

I Veith, The Yellow Emperor’s classic of internal medicine. (1972) University of California Press, Berkeley ; (translator).

SH Wang, S Yang, The pulse classic: a translation of the Mai Jing. (1997) Blue Poppy Press, Boulder, CO ; (translator).

WHO, Guidelines on basic training and safety in acupuncture. (1999) World Health Organization, Geneva .