112 Constipation

Clinical Presentation

Differential Diagnosis

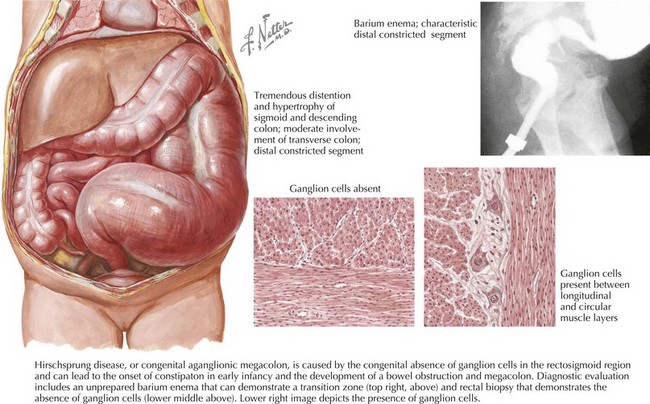

Although the majority of children with constipation have functional disease, it is important to consider the broad differential diagnosis of constipation in the pediatric population (Box 112-1). Patients with an organic disease usually present with a range of symptoms or physical findings in addition to constipation. Children with Hirschsprung’s disease (Figure 112-1) often do not pass meconium during the first 36 hours of life and have problems with constipation beginning in infancy (Table 112-1). On examination, the rectum is generally very small and empty of stool. Patients with constipation secondary to hypothyroidism generally have other symptoms and findings, including lethargy, hypotonia, a large fontanelle if presenting in infancy, short stature, cold intolerance, dry skin, feeding problems, and a palpable goiter (see Chapter 68). Celiac disease can also present with constipation in addition to poor growth and abdominal pain. Children with lead poisoning can present with constipation in addition to vomiting and intermittent abdominal pain. Patients with a tethered spinal cord may have a sacral dimple and motor deficits of the lower extremities on physical examination. In general, patients with constipation secondary to an organic illness rather than functional constipation have some additional finding or red flag on the history or physical examination to warrant further investigation.

Table 112-1 Distinguishing Functional Constipation from Hirschsprung’s Disease

| Functional Constipation | Hirschsprung’s Disease | |

|---|---|---|

| Onset | Rare in infancy | Common in infancy |

| Delayed passage of meconium | Rare | Common |

| Encopresis | Common | Unusual |

| Stool size | Very large | Small, ribbonlike |

| Failure to thrive | Rare | Common |

| Abdominal distension | Variable | Common |

| Painful defecation | Common | Rare |

| Stool in rectal vault | Common | Rare |

| Anal tone | Open, distended | Tight |

Adapted from Graham-Maar RC, Ludwig S, Markowtiz J: Constipation. In Fleisher, Ludwig (eds): Textbook of Pediatric Emergency Medicine, ed 5. Philadelphia, Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins, 2006 and Behrman RE, Kliegman RM: Nelson Essentials of Pediatrics, ed 4. St. Louis, Saunders, 2002.

Evaluation and Management

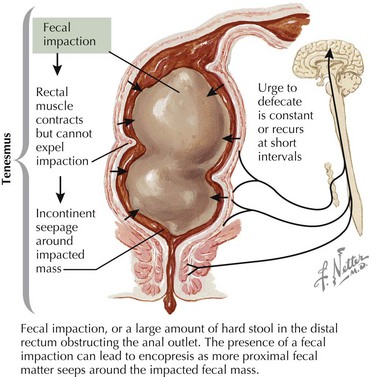

Treatment of functional constipation generally involves determining whether a fecal impaction is present, treating the impaction, initiating maintenance treatment with oral medication, and educating the patient and the family. Fecal impaction (Figure 112-2) is defined as a hard mass in the lower abdomen on physical examination, a dilated rectum filled with a large amount of hard stool on rectal examination or excessive stool on abdominal radiography. Disimpaction must occur before maintenance therapy can be effective and is best accomplished by the rectal route with phosphate enemas, saline enemas, or mineral oil enemas. An oral approach to disimpaction is slower and less effective than rectal disimpaction, but if necessary, it can be attempted with high doses of polyethylene glycol electrolyte solutions or with high-dose magnesium hydroxide, magnesium citrate, lactulose, sorbitol, senna, mineral oil, or bisacodyl.

Baker SS, Liptak GS, Colletti RB, et al. Constipation in infants and children: evaluation and treatment. A medical position statement of the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1999;29(5):612-626.

Benninga M, Candy DC, Catto-Smith AG, et al. The Paris Consensus on Childhood Constipation Terminology (PACCT) Group. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2005;40(3):273-275.

Borowitz SM, Cox DJ, Kovatchev B, et al. Treatment of childhood constipation by primary care physicians: efficacy and predictors of outcome. Pediatrics. 2005;115:873-877.

Evaluation and treatment of constipation in children: summary of updated recommendations of the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology. Hepatology and Nutrition. North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2006;43(3):405-407.