CHAPTER 18 Constipation

DEFINITION AND PRESENTING SYMPTOMS

The definition of constipation varies among people, and it is important to ask patients what they mean when they say “I am constipated.” Most persons are describing a perception of difficulty with bowel movements or a discomfort related to bowel movements. The most common terms used by young healthy adults to define constipation are straining (52%), hard stools (44%), and the inability to have a bowel movement (34%).1

The definition of constipation also varies among physicians and other health care providers. The traditional medical definition of constipation, based on the 95% lower confidence limit for healthy adults in North America and the United Kingdom,2 has been three or fewer bowel movements/week. Reports of stool frequency, however, are often inaccurate and do not correlate with complaints of constipation.3 In an attempt to standardize the definition of constipation, a consensus definition was initially developed by international experts in 1992 (Rome I criteria)4 and was revised in 1999 and in 2006 (Rome II and III criteria, respectively; Table 18-1).5,6

| Two or more of the following six must be present*: |

* Criteria fulfilled for the previous three months with symptom onset at least six months prior to diagnosis. In addition, loose stools should rarely be present without the use of laxatives, abdominal pain is not required, and there should be insufficient criteria for irritable bowel syndrome. These criteria may not apply when the patient is taking laxatives.

The Rome criteria incorporate the multiple symptoms of constipation, of which stool frequency is only one, and require that a minimum of two symptoms be present at least 25% of the time. Unlike the Rome I criteria, the Rome II criteria include symptoms suggestive of outlet obstruction (e.g., a sensation of anorectal blockage or obstruction and use of maneuvers to facilitate defecation). The Rome III criteria allow patients to have occasional loose stools and require that symptoms be present during the previous three months, with an onset at least six months earlier. When abdominal pain or discomfort is the predominant symptom, irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), rather than constipation, should be considered to be the diagnosis (see Chapter 118). Intermittently loose stools unrelated to laxative use also suggest a diagnosis of IBS. Although distinguishing IBS from constipation alone is important, the symptoms and pathophysiology of these entities overlap substantially.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

PREVALENCE

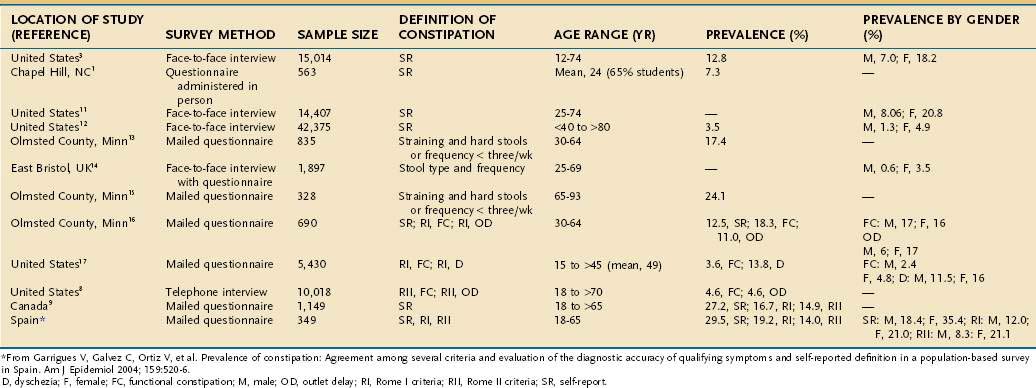

The prevalence of constipation ranges from 2% to 28% of the population in Western countries (Table 18-2)7–17 and varies depending on the demographics of the population, definition of constipation (e.g., self-reported symptoms, fewer than three bowel movements/week, or the Rome criteria), and method of questioning (e.g., postal questionnaire, interview). Some studies have attempted to identify subcategories of constipation based on the symptom pattern. In general, the prevalence is highest when constipation is self-reported9 and lowest when the Rome II criteria for constipation are applied. When the Rome II criteria are used to diagnose constipation, the effects of gender, race, socioeconomic status, and level of education on the prevalence of constipation are reduced.10

INCIDENCE

Little is known about the incidence of constipation in the general population. Talley and colleagues studied 690 nonelderly residents of Olmsted County, Minnesota, at baseline and after 12 to 20 months.18 Constipation, defined as frequent straining at stool and passing hard stool, a stool frequency of fewer than three stools/week, or both, was present in 17% of respondents on the first survey and 15% on the second survey. The rate of new constipation in this study was 50/1000 person-years, whereas the disappearance rate was 31/1000 person-years. Robson and colleagues found that 12.5% of older persons (mean age, 83 years) entering a nursing home had constipation and that constipation developed in 7% over three months of follow-up.19

PUBLIC HEALTH PERSPECTIVE

Constipation results in more than 2.5 million physician visits, 92,000 hospitalizations, and several hundred million dollars of laxative sales/year in the United States.20 Eighty-five percent of physician visits for constipation lead to a prescription for laxatives or cathartics.21 The cost of testing alone in patients with constipation has been estimated to be $6.9 billion annually.22 Among patients with constipation seen in a tertiary referral center, the average cost of a medical evaluation was $2,252, with the greatest cost attributed to colonoscopy.23

In an analysis of physician visits for constipation in the United States between 1958 and 1986, 31% of patients who required medical attention were seen by general and family practitioners, followed by internists (20%), pediatricians (15%), surgeons (9%), and obstetricians-gynecologists (9%). Only 4% of patients were seen by gastroenterologists, suggesting that few such patients were deemed to need advice from a specialist.20,21 In a National Canadian Survey, 34% of persons who reported constipation had seen a physician for their symptoms.9

RISK FACTORS

Risk factors for constipation in the United States include female gender, advanced age, nonwhite ethnicity, low levels of income and education, and low level of physical activity.3,8,11,24 Other risk factors include use of certain medications and particular underlying medical disorders (see later). Diet and lifestyle also may play a role in the development of constipation (Table 18-3).

Table 18-3 Risk Factors for Constipation

GENDER

The prevalence of self-reported constipation is two to three times higher in women than in men,10–1216 and infrequent bowel movements (e.g., once a week) are reported almost exclusively by women.25 In one study of 220 normal subjects eating their normal diets, 17% of women, but only 1% of men, passed less than 50 g of stool daily.26 The reason for the female predominance is unknown. A reduction in levels of steroid hormones has been observed in women with severe idiopathic constipation, although the clinical significance of this finding is dubious.27 An overexpression of progesterone receptors on colonic smooth muscle cells has been reported to down-regulate contractile G proteins and up-regulate inhibitory G proteins.28

In addition, overexpression of progesterone receptor B on colonic muscle cells, thereby making them more sensitive to physiologic concentrations of progesterone, has been proposed as an explanation for severe slow-transit constipation in some women.29

AGE

The prevalence of self-reported constipation among older adults ranges from 15% to 30%, with most,7,21,24,30,31 but not all,8,9,12,17 studies showing an increase in prevalence with age. Constipation is particularly problematic in nursing home residents, among whom constipation is reported in almost half and 50% to 74% use laxatives on a daily basis.32,33 Similarly, hospitalized older patients appear to be at high risk of developing constipation. A study of patients on a geriatrics ward in the United Kingdom showed that up to 42% had a fecal impaction.34

Older adults also tend to seek medical assistance for constipation more commonly than their younger counterparts. In an analysis of physician visits for constipation in the United States between 1958 and 1986, the frequency was about 1% in persons younger than 60, between 1% and 2% in those 60 to 65, and between 3% and 5% in those older than 65 years.21

Constipation in older adults is most commonly the result of excessive straining and hard stools30 rather than a decrease in stool frequency. In a community sample of 209 people ages 65 to 93 years, the main symptom used to describe constipation was the need to strain at defecation; 3% of men and 2% of women reported that their average bowel frequencies were less than three/week.29 Possible causes for the increased frequency of straining in older adults include decreased food intake, reduced mobility, weakening of abdominal and pelvic wall muscles, chronic illness, psychological factors, and medications, particularly pain-relieving drugs.19,32

Constipation is also common in children younger than 4 years.33 For example, in Great Britain, the frequency of a consultation for constipation in general practice was 2% to 3% for children ages 0 to 4, approximately 1% for women ages 15 to 64, 2% to 3% for both genders ages 65 to 74, and 5% to 6% for patients ages 75 years or older. Fecal retention with fecal soiling is a common cause of impaired quality of life and the need for medical attention in childhood.

ETHNICITY

In North America, constipation is reported more commonly by nonwhites than whites. In a survey of 15,014 persons, the frequency of constipation in whites was 12.2%, compared with 17.3% in nonwhites.3 Both groups demonstrate similar age-specific increases in prevalence.7 In developing countries, constipation is less common among the native populations, in whom stool weights are three to four times more than the median of 106 g daily in Britain.26 In rural Africa, constipation appears to be rare.

SOCIOECONOMIC CLASS AND EDUCATION LEVEL

The prevalence of constipation is influenced by socioeconomic status. In population-based surveys, subjects with a lower income status have higher rates of constipation as compared with those who have a higher income.3,6–8 In a survey of approximately 9000 Australians, men and women of lower socioeconomic status were more likely to report constipation than those of higher socioeconomic status.35 Similarly, persons who have less education tend to have an increased prevalence of constipation as compared with those who have more education.3,8,9,11,16

DIET AND PHYSICAL ACTIVITY

Cross-sectional studies have not linked low intake of fiber with constipation,29,36 yet data suggest that increased consumption of fiber decreases colonic transit time and increases stool weight and frequency.22 An analysis from the Nurses Health Study, which assessed the self-reported bowel habits of 62,036 women between the ages of 36 and 61 years, demonstrated that women who were in the highest quintile of fiber intake and who exercised daily were 68% less likely to report constipation than women who were in the lowest quintile of fiber intake and exercised less than once a week.24 Although other observational studies have supported a protective effect of physical activity on constipation, results from trials designed to test this hypothesis are conflicting. In a trial designed to assess the effect of regular exercise on chronic constipation, symptoms did not improve after a four-week exercise program.37 In healthy sedentary subjects, a nine-week program of progressively increasing exercise had no consistent effect on whole-gut transit time or stool weight.38

Dehydration has been identified as a potential risk factor for constipation. Some but not all observational studies have found an association between slowed intestinal transit time and dehydration.36,39 Although patients with constipation are advised routinely to increase their intake of fluid, the benefit of increased fluid intake has not been investigated thoroughly.

MEDICATION USE

Persons who use certain medications are at a substantially higher risk of constipation. In a review of 7251 patients with chronic constipation (and nonconstipated controls) from a general practice database, medications that were significantly associated with constipation were opioids, diuretics, antidepressants, antihistamines, antispasmodics, anticonvulsants, and aluminum antacids (Table 18-4).40 The use of aspirin or other nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in the older population is associated with a small but significantly increased risk of constipation.14

| Mechanical Obstruction |

COLONIC FUNCTION

LUMINAL CONTENTS

The main contents of the colonic lumen are food residue, water and electrolytes, bacteria, and gas. Unabsorbed food entering the cecum contains carbohydrates that are resistant to digestion and absorption by the small intestine, such as starches and nonstarch polysaccharides (NSPs). Some of the unabsorbed carbohydrate serves as substrate for bacterial proliferation and fermentation, yielding short-chain fatty acids and gas (see Chapter 16). On average, bacteria represent approximately 50% of stool weight.41 In an analysis of feces from nine healthy subjects on a metabolically controlled British diet, bacteria constituted 55% of the total solids, and fiber represented approximately 17% of the stool weight.42

A meta-analysis of the effect of wheat bran on colonic function has suggested that bran increases stool weight and decreases mean colonic transit time in healthy volunteers.42 The effect of bran may be the result primarily of increased bulk within the colonic lumen; the increased bulk stimulates propulsive motor activity. The particulate nature of some fibers also may stimulate the colon. For example, ingestion of coarse bran, 10 g twice daily, was shown to reduce colonic transit time by about one third, whereas ingestion of the same quantity of fine bran led to no significant decrease.41 Similarly, ingestion of inert plastic particles similar in size to coarse bran increased fecal output by almost three times their own weight and decreased colonic transit time.43

ABSORPTION OF WATER AND SODIUM

The colon avidly absorbs sodium and water (see Chapter 99). Increased water absorption can lead to smaller, harder stools. The colon extracts most of the 1000 to 1500 mL of fluid that crosses the ileocecal valve, and leaves only 100 to 200 mL of fecal water daily. Less reabsorption of electrolytes and nutrients takes place in the colon than in the small intestine, and sodium-chloride exchange and short-chain fatty acid transport are the principal mechanisms for stimulating water absorption. Colonic absorptive mechanisms remain intact in patients with constipation. One proposed pathophysiologic mechanism in slow-transit constipation is that the lack of peristaltic movement of contents through the colon allows more time for bacterial degradation of stool solids and increased NaCl and water absorption, thereby decreasing both stool weight and frequency.44 The volume of stool water and quantity of stool solids seem to be reduced proportionally in constipated persons.45

DIAMETER AND LENGTH

A wide or long colon may lead to a slow colonic transit rate (see Chapter 96). Although only a small fraction of patients with constipation have megacolon or megarectum, most patients with dilatation of the colon or rectum report constipation. Colonic width can be measured on barium enema films. A width of more than 6.5 cm at the pelvic brim is abnormal and has been associated with chronic constipation.46

MOTOR FUNCTION

Colonic muscle has four main functions (see also Chapter 98): (1) delays passage of the luminal contents so as to allow time for the absorption of water; (2) mixes the contents and allows contact with the mucosa; (3) allows the colon to store feces between defecations; and (4) propels the contents toward the anus. Muscle activity is affected by sleep and wakefulness, eating, emotion, the contents of the colon, and drugs. Nervous control is partly intrinsic and partly extrinsic by the sympathetic nerves and the parasympathetic sacral outflow.

Transit of contents along the colon takes hours or days (longer than transit in other portions of the gastrointestinal tract). In a study of 73 healthy subjects, the mean colonic transit time was 35 hours.47 In another similar study, the mean colonic transit time in healthy volunteers was 34 hours, with an upper limit of normal of 72 hours.48

Scintigraphic studies in constipated subjects have shown that overall transit of colonic contents is slow. In some patients, the rate of movement of contents is approximately normal in the ascending colon and hepatic flexure but delayed in the transverse and left colon. Other patients show slow transit in the right and left sides of the colon.49

Colonic propulsions are of two basic types, low-amplitude propagated contractions (LAPCs) and high-amplitude propagated contractions (HAPCs).50 The frequency and duration of HAPCs are reduced in some patients with constipation. In one study, 14 chronically constipated patients with proved slow transit of intestinal contents and one or fewer bowel movements weekly were compared with 18 healthy subjects. Four of the patients had no peristaltic movement, whereas peristaltic movement was normal in all the healthy subjects during a 24-hour period. Peristaltic movements in other subjects with constipation were fewer in number and shorter in duration, and thus passed for a shorter distance along the colon, as compared with the findings in the healthy controls. All the healthy subjects reported abdominal discomfort or an urge to defecate during peristaltic movements, and two defecated, whereas only four of the 14 subjects with constipation experienced any sensation during such movements, and none defecated.51

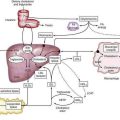

INNERVATION AND THE INTERSTITIAL CELLS OF CAJAL

Proximal colonic motility is under the involuntary control of the enteric nervous system, whereas defecation is voluntary. Slow-transit constipation may be related to autonomic dysfunction.52,53 Histologic studies have shown abnormal numbers of myenteric plexus neurons involved in excitatory or inhibitory control of colonic motility, thereby resulting in decreased amounts of the excitatory transmitter substance P54 and increased amounts of the inhibitory transmitters vasoactive intestinal polypeptide (VIP) or nitric oxide (NO).55

Interstitial cells of Cajal (ICCs) are the intestinal pacemaker cells and play an important role in regulating gastrointestinal motility. They facilitate the conduction of electrical current and mediate neural signaling between enteric nerves and muscles. ICCs initiate slow waves throughout the gastrointestinal tract. Confocal images of ICCs in patients with slow-transit constipation show not only reduced numbers but also abnormal morphology of ICCs, with irregular surface markings and a decreased number of dendrites. In patients with slow-transit constipation, the number of ICCs has been shown to be decreased in the sigmoid colon56 or the entire colon.57,58 Pathologic examination of colectomy specimens of 14 patients with severe intractable constipation has revealed decreased numbers of ICCs and myenteric ganglion cells throughout the colon.59

DEFECATORY FUNCTION

The process of defecation in healthy persons begins with a predefecatory period, during which the frequency and amplitude of propagating sequences (three or more successive pressure waves) are increased. Stimuli such as waking and meals (gastroileal reflex, also referred to as gastrocolic reflex) can stimulate this process. This predefecatory period is blunted, and may be absent, in patients with slow-transit constipation.50 The gastroileal reflex also is diminished in persons with slow-transit constipation. Stool is often present in the rectum before the urge to defecate arises. The urge to defecate is usually experienced when stool comes into contact with receptors in the upper anal canal. When the urge to defecate is resisted, retrograde movement of stool may occur and transit time increases throughout the colon (see Chapter 98).60

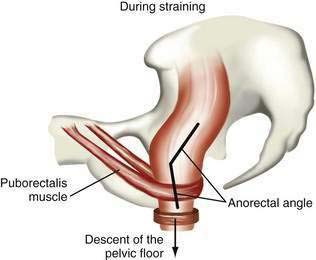

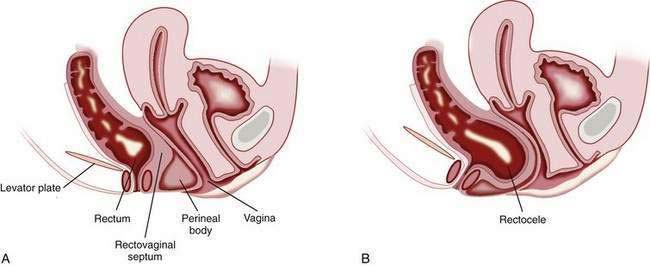

Although the sitting or squatting position seems to facilitate defecation, the benefit of squatting has not been studied in patients with constipation. Full flexion of the hips stretches the anal canal in an anteroposterior direction and straightens the anorectal angle, thereby promoting emptying of the rectum.61 Contraction of the diaphragm and abdominal muscles raises intrapelvic pressure, and the pelvic floor relaxes simultaneously. Striated muscular activity expels rectal contents, with little contribution from colonic or rectal propulsive waves. Coordinated relaxation of the puborectalis muscle, which maintains the anorectal angle, and external anal sphincter at a time when pressure is increasing in the rectum results in expulsion of stool (Fig. 18-1).

The length of the colon emptied during spontaneous defecation varies but most commonly extends from the descending colon to the rectum.62 When the propulsive action of smooth muscle is normal, defecation usually requires minimal voluntary effort. If colonic and rectal waves are infrequent or absent, however, the normal urge to defecate may not occur.51

SIZE AND CONSISTENCY OF STOOL

In a study of normal subjects who were asked to expel single hard spheres of different sizes from the rectal ampulla, the intrarectal pressure and time needed to pass the objects varied inversely with their diameters. Small hard stools are more difficult to pass than large soft stools. When larger stimulated stools were tested, a hard stool took longer to expel than a soft silicone rubber object of approximately the same shape and volume. Similarly, more subjects were able to expel a 50-mL water-filled compressible balloon than a hard 1.8-cm sphere.63

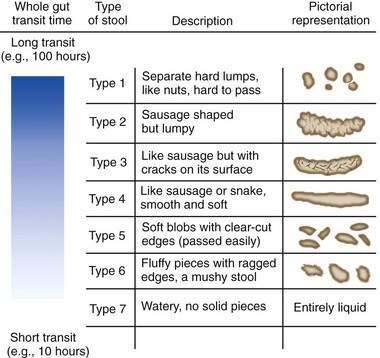

Human stools may vary in consistency from small hard lumps to liquid. The water content of stool determines consistency. Rapid colonic transit of fecal residue leads to diminished water absorption and (perhaps counterintuitively) an increase in the bacterial content of the stool. The Bristol Stool Scale25 is used in the assessment of constipation and is regarded as the best descriptor of stool form and consistency (Fig. 18-2). Stool consistency appears to be a better predictor of whole-gut transit time than of defecation frequency or stool volume.64

CLASSIFICATION

Mechanical small and large bowel obstruction, medications, and systemic illnesses can cause constipation, and these causes of secondary constipation must be excluded, especially in patients presenting with a new onset of constipation (see Table 18-4). Most often, however, constipation is caused by disordered function of the colon or rectum (functional constipation). Functional constipation can be divided into three broad categories—normal-transit constipation, slow-transit constipation, and defecatory or rectal evacuation disorders (Table 18-5). In a study of more than 1000 patients with functional constipation who were evaluated at the Mayo Clinic, 59% were found to have normal-transit constipation, 25% had defecatory disorders, 13% had slow-transit constipation, and 3% had a combination of a defecatory disorder and slow-transit constipation.65

Table 18-5 Clinical Classification of Functional Constipation

| CATEGORY | FEATURES | CHARACTERISTIC FINDINGS |

|---|---|---|

| Normal-transit constipation | Incomplete evacuation; abdominal pain may be present but not a predominant feature | Normal physiologic test results |

| Slow-transit constipation | Infrequent stools (e.g., ≤1/wk); lack of urge to defecate; poor response to fiber and laxatives; generalized symptoms, including malaise and fatigue; more prevalent in young women | Retention in colon of >20% of radiopaque markers five days after ingestion |

| Defecatory disorders (pelvic floor dysfunction, anismus, descending perineum syndrome, rectal prolapse) | Frequent straining; incomplete evacuation; need for manual maneuvers to facilitate defecation | Abnormal balloon expulsion test and/or rectal manometry |

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

NORMAL-TRANSIT CONSTIPATION

In normal-transit constipation, stool travels along the colon at a normal rate.66 Patients with normal-transit constipation may have misperceptions about their bowel frequencies and often exhibit psychosocial distress.67 Some patients have abnormalities of anorectal sensory and motor function indistinguishable from those in patients with slow-transit constipation.68 Whether increased rectal compliance and reduced rectal sensation are effects of chronic constipation or contribute to the failure of the patients to experience an urge to defecate is unclear. Most patients, however, have normal physiologic testing. IBS with constipation differs from normal-transit constipation in that abdominal pain is the predominant symptom in IBS (see Chapter 118).

SLOW-TRANSIT CONSTIPATION

Slow-transit constipation is most common in young women and is characterized by infrequent bowel movements (less than one bowel movement/week). Associated symptoms include abdominal pain, bloating, and malaise. Symptoms are often intractable, and conservative measures such as fiber supplements and osmotic laxatives are usually ineffective.69,70 The onset of symptoms is gradual and usually occurs around the time of puberty. Slow-transit constipation arises from disordered colonic motor function. Patients who have mild delays in colonic transit have symptoms similar to those seen in persons with IBS.71 In patients with more severe symptoms, the pathophysiology includes delayed emptying of the proximal colon and fewer HAPCs after meals. Colonic inertia is a term used to describe the disorder in patients with symptoms at the severe end of the spectrum. In this condition, colonic motor activity fails to increase after a meal,72 ingestion of bisacodyl,73 or administration of a cholinesterase inhibitor such as neostigmine.74

DEFECATORY DISORDERS

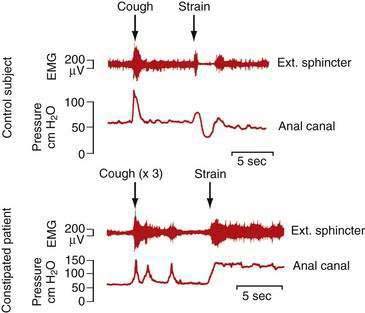

Defecatory disorders arise from failure to empty the rectum effectively because of an inability to coordinate the abdominal, rectoanal, and pelvic floor muscles. Many patients with defecatory disorders also have slow-transit constipation75 Defecatory disorders are also known as anismus, dyssynergia, pelvic floor dyssynergia, spastic pelvic floor syndrome, obstructive defecation, or outlet obstruction. These disorders appear to be acquired and may start in childhood. They may be a learned behavior to avoid some discomfort associated with the passage of large hard stools or pain associated with attempted defecation in the setting of an active anal fissure or inflamed hemorrhoids. Patients with defecatory disorders commonly have inappropriate contraction of the anal sphincter when they bear down (Fig. 18-3). This phenomenon can occur in asymptomatic subjects but is more common among patients who complain of difficult defecation.76 Some patients with a defecatory disorder are unable to raise intrarectal pressure to a level sufficient to expel stool, a disturbance that manifests clinically as failure of the pelvic floor to descend on straining.77

Defecatory disorders are particularly common in older patients with chronic constipation and excessive straining, many of whom do not respond to standard medical treatment.78 Defecatory disorders rarely are associated with structural abnormalities such as rectal intussusception, an obstructing rectocele, megarectum, or excessive perineal descent.79

Patients with defecatory disorders may report infrequent bowel movements, ineffective and excessive straining, and the need for manual disimpaction; however, symptoms, particularly in the case of pelvic floor dysfunction, do not correlate with physiologic findings.80 For a diagnosis of a defecatory disorder, a Rome working group81 has specified the criteria listed in Table 18-6. In patients with this disorder, constipation is functional and caused by dysfunction of the pelvic floor muscles as determined by physiologic tests. Pelvic floor dyssynergia is a subset of these patients in which the anal sphincter fails to relax more than 20% of its basal resting pressure during attempted defecation, despite the presence of adequate propulsive forces in the rectum.

Table 18-6 Rome III Criteria for Functional Defecation Disorders81*

| The patient must satisfy diagnostic criteria for functional constipation (see Table 18-1). |

| During repeated attempts to defecate, the patient must have at least two of the following: |

EMG, electromyography.

* Criteria fulfilled for the previous three months with symptom onset at least six months prior to diagnosis.

Functional fecal retention (FFR) is the most common defecatory disorder in children. It is a learned behavior that results from withholding defecation, often because of fear of a painful bowel movement.82 The symptoms are common and may result in secondary encopresis (fecal incontinence) because of leakage of liquid stool around a fecal impaction. FFR is the most common cause of encopresis in childhood (see Chapter 17).83

DISORDERS OF THE ANORECTUM AND PELVIC FLOOR

RECTOCELE

A rectocele is the bulging or displacement of the rectum through a defect in the anterior rectal wall. In women, the perineal body supports the anterior rectal (posterior vaginal) wall above the anorectal junction, and a layer of fascia runs from the rectovaginal pouch of Douglas to the perineal body and adheres to the posterior vaginal wall. The anterior rectal wall is unsupported above the level of the perineal body, and the rectovaginal septum can bulge anteriorly to form a rectocele (Fig. 18-4). Rectoceles can arise from damage to the rectovaginal septum or its supporting structures during vaginal childbirth. These injuries are exacerbated by repetitive increases in intra-abdominal pressure and the long-term effects of gravity. Prolapse of other pelvic organs may be present. For example, urinary incontinence, as well as a previous hysterectomy, has been reported to be more common in patients with a rectocele than in patients with difficult defecation but no demonstrable rectocele.84

Studies using defecating proctography (see later) have shown that rectoceles are common in symptomless healthy women and may protrude as much as 4 cm from the line of the anterior rectal wall without causing bowel symptoms, although 2 cm is the generally accepted lower limit of a rectocele that may be regarded as clinically significant.85 Symptomatic patients report the inability to complete fecal evacuation, perineal pain, sensation of local pressure, and appearance of a bulge at the vaginal opening on straining. Women may report the need to use their thumb or fingers to support the posterior vaginal wall to complete defecation.84 Women also may report the need to use a finger to evacuate the rectum digitally.

Defecating proctography can be used to demonstrate a rectocele, measure its size, and determine whether barium becomes trapped within the rectocele. In one study, trapping of barium in rectoceles changed with the degree of rectal emptying and was related to the size of the rectocele86; however, the size of the rectocele or degree of emptying on defecation has not been shown to correlate with the outcome of surgical repair.87,88

Asymptomatic women with rectoceles do not require surgical treatment. Kegel exercises (designed to strengthen the pelvic floor muscles that support the urethra, bladder, uterus, and rectum) and instructions to avoid repetitive increases in intra-abdominal pressure may help prevent progression of the rectocele. Surgery should be considered only for patients in whom contrast is retained during defecography and patients in whom constipation is relieved with digital vaginal pressure to facilitate defecation.89 Surgical repair can be performed by endorectal, transvaginal, or transperineal approaches. Other types of genital prolapse may also be present, and collaboration between the surgeon and gynecologist may be appropriate. In carefully selected patients surgical repair benefits approximately 75% of patients. In a review of 89 women who underwent a combined transvaginal and transanal rectocele repair for symptoms of obstructive defecation, the repair was successful in 71% of patients, as assessed by the absence of symptoms after one year.90 Reduction in the size of the rectocele, as judged by defecating proctography, does not appear to correlate clearly with improvement in symptoms.88

DESCENDING PERINEUM SYNDROME

In the descending perineum syndrome, the pelvic floor descends to a greater extent than normal (1 to 4 cm) when the patient strains during defecation, and rectal expulsion is difficult. The anorectal angle is widened as a result of pelvic floor weakness, and the rectum is more vertical than normal. The perineal body is weak (thereby facilitating formation of a rectocele), and the lax muscular support favors intrarectal mucosal intussusception or rectal prolapse. The pelvic floor may not provide the resistance necessary for extrusion of solid stool through the anal canal. A common reason for pelvic floor weakness is trauma or stretching during parturition. In some cases, repeated and prolonged defecation appears to be a damaging factor. Symptoms include constipation, incomplete rectal evacuation, excessive straining and, less commonly, digital rectal evacuation.91 Electrophysiologic studies show partial denervation of the striated muscle and evidence of pudendal nerve damage. Histologic examination of operative specimens of the pelvic floor muscles confirms loss of muscle fibers.

DIMINISHED RECTAL SENSATION

The urge to defecate depends in part on tension within the rectal wall (determined by the tone of the circular muscle of the rectal wall), rate and volume of rectal distention, and size of the rectum. Some patients with constipation appear to feel pain normally as the rectum is distended to the maximal tolerable volume, but they fail to experience an urge to defecate with intermediate volumes.92 In a study of women with severe idiopathic constipation, a higher than normal electrical stimulation current applied to the rectal mucosa was required to elicit pain, thereby suggesting a possible rectal sensory neuropathy.93

Rectal hyposensitivity (RH) is defined as insensitivity of the rectum to balloon distention on anorectal physiologic investigation, although the pathophysiology of RH is not entirely clear. Constipation is the most common presenting symptom of RH. In an investigation of 261 patients with RH, 38% had a history of pelvic surgery, 22% had a history of anal surgery, and 13% had a history of spinal trauma.94

RECTAL PROLAPSE AND SOLITARY RECTAL ULCER SYNDROME

Rectal prolapse refers to complete protrusion of the rectum through the anus (see Chapter 125). Occult (asymptomatic) rectal prolapse has been found in 33% of patients with clinically recognized rectoceles and defecatory dysfunction.95 Rectal prolapse can be detected easily on physical examination by asking the patient to strain as if to defecate. A laparoscopic rectopexy—in which the prolapsed rectum is raised and secured with sutures to the adjacent fascia—is the recommended treatment.96

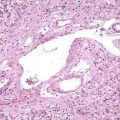

Solitary rectal ulcer syndrome is a rare disorder characterized by erythema or ulceration generally of the anterior rectal wall as a result of chronic straining (see Chapter 115). Mucus and blood may be passed when the patient strains during defecation.97,98 Endoscopic findings may include erythema, hyperemia, mucosal ulceration, and polypoid lesions. Misdiagnosis may occur because of the heterogeneous findings and misleading name of the syndrome (an ulcer need not be present). In a study of 98 patients with solitary rectal ulcer syndrome, 26% were initially diagnosed incorrectly. In patients with a rectal ulcer or mucosal hyperemia, the most common misdiagnoses were Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. In those with a polypoid lesion, the most common misdiagnosis was a neoplastic polyp.99 Histology of full-thickness specimens of the lesion reveals extension of the muscularis mucosa between crypts and disorganization of the muscularis propria. Defecography, transrectal ultrasonography, and anorectal manometry are helpful in the diagnosis.

Varying degrees of rectal prolapse exist in association with solitary rectal ulcer syndrome. Rectal prolapse and paradoxical contraction of the puborectalis muscle can lead to rectal trauma because of the high pressures generated within the rectum. In addition, rectal mucosal blood flow is reduced.100

Medical treatment may be difficult, and a single optimal therapy does not exist. The patient should be advised to resist the urge to strain. Bulk laxatives and dietary fiber may be of some benefit.101 Surgery may be required; rectopexy is performed most commonly. Of patients who undergo surgery for solitary rectal ulcer syndrome with rectal prolapse, 55% to 60% report long-term satisfaction, although a colostomy is eventually required in approximately one third of patients.102 Repair of a rectal prolapse may aggravate constipation. Biofeedback appears to be a promising mode of therapy for patients with solitary rectal ulcer syndrome.103

SYSTEMIC DISORDERS

HYPOTHYROIDISM

Constipation is the most common gastrointestinal complaint in patients with hypothyroidism. The pathologic effects are caused by an alteration of intestinal motor function and possible infiltration of the intestine by myxedematous tissue. The basic electrical rhythm that generates peristaltic waves in the duodenum decreases in hypothyroidism, and small bowel transit time is increased.104 Myxedema megacolon is rare but can result from myxedematous infiltration of the muscle layers of the colon. Symptoms include abdominal pain, flatulence, and constipation.105

DIABETES MELLITUS

The mean colonic transit time is longer in diabetics than in healthy controls. In one study, the mean total colonic transit time in 28 diabetic patients (34.9 ± 29.6 hours; mean ± SD) was significantly longer than that in 28 healthy subjects (20.4 ± 15.6 hours; P < 0.05).106 Among the 28 diabetic patients, 9 of 28 (32%) met the Rome II criteria for constipation and 14 of 28 (50%) had cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy. The mean colonic transit times in diabetic patients with and without cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy were similar. By contrast, a previous study reported that asymptomatic diabetic patients with cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy had significantly longer whole-gut transit times (although still within the range of normal) than a control group without evidence of neuropathy.107 In another study, diabetic patients with mild constipation demonstrated delayed colonic myoelectrical and motor responses after ingestion of a standard meal, whereas diabetics with severe constipation had no increases in these responses after food. Neostigmine increased colonic motor activity in all diabetic patients, suggesting that the defect was neural rather than muscular (see Chapter 35).108

NERVOUS SYSTEM DISEASE

PARKINSON’S DISEASE

Constipation occurs frequently in patients with Parkinson’s disease (PD). In a study of 12 patients with PD compared with normal controls, slow colonic transit, decreased phasic rectal contractions, weak abdominal wall muscle contraction, and paradoxical anal sphincter contraction on defecation were all features in patients with PD and frequent constipation.110 Loss of dopamine-containing neurons in the central nervous system is the underlying defect in PD; a defect in dopaminergic neurons in the enteric nervous system also may be present. Histopathologic studies of the myenteric plexuses of the ascending colon in 11 patients with PD and constipation revealed that in 9 patients, the number of dopamine-positive neurons was one tenth or less the number in control subjects. Dopamine concentrations in the muscularis externa were significantly lower in patients with PD than in controls (P < 0.01).111

Another possible contributor to constipation is the inability of some patients with PD to relax the striated muscles of the pelvic floor on defecation. This finding is a local manifestation of the extrapyramidal motor disorder that affects skeletal muscle. Preliminary observations suggest that injection of botulinum toxin into the puborectalis muscle is a potential therapy for this type of outlet dysfunction constipation in patients with PD.112,113

MULTIPLE SCLEROSIS

Constipation is common among patients with multiple sclerosis (MS). In an unselected group of 280 patients with MS, the frequency of constipation (defined as diminished bowel frequency, digitation to facilitate defecation, or the use of laxatives) was approximately 43%. Almost 25% of the subjects passed fewer than three stools/week, and 18% used a laxative more than once a week. Constipation correlated with the duration of MS but preceded the diagnosis of MS in 45% of subjects. Constipation did not correlate with immobility or the use of medications.114 In another questionnaire study of 221 patients with MS, the frequency of constipation was as high as 54%.115 Constipation in patients with MS can be multifactorial and related to a reduction in postprandial colonic motor activity, limited physical activity, and medications with constipating side effects.

Patients with advanced MS and constipation have evidence of a visceral neuropathy. In a group of patients with advanced MS and severe constipation, all had evidence of disease in the lumbosacral spinal cord and decreased compliance of the colon. Motor and electrophysiologic measurements have shown that the usual increase in colonic motor activity after meals is absent. Among less severely affected patients, slow colonic transit and manometric evidence of pelvic floor muscular and anal sphincter dysfunction have been demonstrated. Patients may have fecal incontinence.116,117 Therapy with biofeedback has been reported to relieve constipation and fecal incontinence, although in a study of 13 patients with MS who underwent biofeedback for either constipation or incontinence, only 38% improved (see Chapter 17).118

SPINAL CORD LESIONS

Lesions Above the Sacral Segments

Spinal cord lesions or injury above the sacral segments lead to an upper motor neuron disorder, with severe constipation. The resulting delay in colonic transit affects the rectosigmoid colon primarily.119,120 In a study of patients with severe thoracic spinal cord injury, colonic compliance was abnormal, with a rapid rise in colonic pressure on instillation of relatively small volumes of fluid. Motor activity after meals did not increase, but the colonic response to neostigmine was normal, thereby suggesting absence of myopathy.

Studies of anorectal function in patients with severe traumatic spinal cord injury have shown that rectal sensation to distention is abolished, although a dull pelvic sensation is experienced by some patients at maximum levels of rectal balloon distention. Anal relaxation on rectal distention is exaggerated and occurs at a lower balloon volume than in normal subjects. Distention of the rectum leads to a linear increase in rectal pressure, without the plateau at intermediate values seen in normal subjects, and ends in high-pressure rectal contractions after a relatively small volume (100 mL) has been instilled into the balloon. As expected, the rectal pressure generated by straining is lower in patients than in control subjects and is less with higher than lower spinal cord lesions. Patients demonstrate a loss of conscious external anal sphincter control, and the sphincter does not relax on straining, suggesting that in normal subjects, descending inhibitory pathways are present.121 These findings explain why some patients with spinal cord lesions experience not only constipation, but also sudden uncontrollable rectal expulsion with incontinence. Other patients cannot empty the rectum in response to laxatives or enemas, possibly because of failure of the external anal sphincter to relax, and they may require manual evacuation.

Electrical stimulation of anterior sacral nerve roots S2, S3, and S4 via electrodes implanted for urinary control in paraplegic patients leads to a rise in pressure within the sigmoid colon and rectum and contraction of the external anal sphincter. Contraction of the rectum and relaxation of the internal anal sphincter persist for a short time after the stimulus ceases. By appropriate adjustment of the stimulus in one study, it was possible for 5 of 12 paraplegic patients to evacuate feces completely and for most of the others to increase the frequency of defecation and reduce the time spent emptying the rectum.122 In another series, left-sided colonic transit time decreased with regular sacral nerve stimulation.123

Lesions of the Sacral Cord, Conus Medullaris, Cauda Equina, and Nervi Erigentes (S2 to S4)

Neural integration of anal sphincter control and rectosigmoid propulsion occurs in the sacral segments of the spinal cord. The motor neurons that supply the striated sphincter muscles are grouped in Onuf’s nucleus at the level of S2. There is evidence that efferent parasympathetic nerves that arise in the sacral segments enter the colon at the region of the rectosigmoid junction and extend distally in the intermuscular plane to reach the level of the internal anal sphincter and proximally to the midcolon via the ascending colonic nerves, which retain the structure of peripheral nerves (see Chapter 98).124

Damage to sacral segments of the spinal cord or to efferent nerves leads to severe constipation. Fluoroscopic studies show a loss of progression of contractions in the left colon. When the colon is filled with fluid, the intraluminal pressure generated is lower than normal, in contrast with the situation after higher lesions of the spinal cord. The distal colon and rectum may dilate, and feces may accumulate in the distal colon. Spasticity of the anal canal can occur. Loss of sensation of the perineal skin may extend to the anal canal, and rectal sensation may be diminished. Rectal wall tone depends on the level of the spinal lesion. In a study of 25 patients with spinal cord injury, rectal tone was significantly higher than normal in patients with acute and chronic supraconal lesions but significantly lower than normal in patients with acute and chronic conal or cauda equina lesions.125

STRUCTURAL DISORDERS OF THE COLON, RECTUM, ANUS, AND PELVIC FLOOR

OBSTRUCTION

Anal atresia in infancy, anal stenosis later in life, or obstruction of the colon may manifest as constipation. Obstruction of the small intestine generally manifests as abdominal pain and distention, but constipation and inability to pass flatus also may be features (see Chapters 96 and 119).

DISORDERS OF SMOOTH MUSCLE

Myopathy Affecting Colonic Muscle

Congenital or acquired myopathy of the colon usually manifests as pseudo-obstruction. The colon is hypotonic and inert (see Chapter 120).

Hereditary Internal Anal Sphincter Myopathy

Hereditary internal anal sphincter myopathy is a rare condition characterized by constipation with difficulty in rectal expulsion and episodes of severe proctalgia fugax, defined as the sudden onset of brief episodes of pain in the anorectal region.126–128 Three affected families have been reported. The mode of inheritance appears to be autosomal dominant with incomplete penetrance. In symptomatic persons, the internal anal sphincter muscle is thickened, and resting anal pressure is increased greatly. In two of the described patients, treatment with a calcium channel blocker improved pain but had no effect on constipation. In another family, two patients were treated by internal anal sphincter strip myectomy; one showed marked improvement and one had improvement in the constipation but only slight improvement in the pain. Examination of the muscle strips showed myopathic changes with polyglucosan bodies (glucose polymers) in the smooth muscle fibers and increased endomysial fibrosis.

Progressive Systemic Sclerosis

Progressive systemic sclerosis (scleroderma) may lead to constipation. In patients with progressive systemic sclerosis and constipation, 9 of 10 had no increase in colonic motor activity after ingestion of a 1000-kcal meal. Histologic examination of colonic specimens from these subjects revealed smooth muscle atrophy of the colonic wall (see Chapter 35).129

Muscular Dystrophies

Muscular dystrophies usually are regarded as disorders of striated muscle, but visceral smooth muscle also may be abnormal. In myotonic muscular dystrophy, a condition in which skeletal muscle fails to relax normally, megacolon may be found, and abnormal function of the anal sphincter is demonstrable.130 Cases associated with intestinal pseudo-obstruction have been reported (see Chapter 120).131

DISORDERS OF ENTERIC NERVES

Congenital Aganglionosis or Hypoganglionosis

Congenital absence or reduction in the number of ganglia in the colon leads to functional colonic obstruction with proximal dilatation, as seen in Hirschsprung’s disease and related conditions (see Chapter 96). In Hirschsprung’s disease, ganglion cells in the distal colon are absent because of an arrest in the caudal migration of neural crest cells in the intestine during embryonic development. Although most patients present during early childhood, often with delayed passage of meconium, some patients with a relatively short segment of involved colon present later in life.132 Typically, the colon narrows at the area that lacks ganglion cells, and the bowel proximal to the narrowing is usually dilated. Two genetic defects have been identified in patients with Hirschsprung’s disease—a mutation in the RET (rearranged during transfection) proto-oncogene, which is involved in the development of neural crest cells, and a mutation in the gene that encodes the endothelin B receptor, which affects intracellular calcium levels.133,134

Hypoganglionosis is reported when small, sparse myenteric ganglia are seen. Neuronal counts can be made on full-thickness tissue specimens and compared with published reference values obtained from autopsy material. Establishing the diagnosis of hypoganglionosis is not easy, because of variations in the normal density of neurons.135 Quantitative declines in the number of neurons in the enteric nervous system also are seen in patients with severe slow-transit constipation and characterized morphologically as oligoneuronal hypoganglionosis.136

Congenital Hyperganglionosis (Intestinal Neuronal Dysplasia)

Congenital hyperganglionosis, or intestinal neuronal dysplasia, is a developmental defect characterized by hyperplasia of the submucosal nerve plexus. Clinical manifestations of the disease are similar to those seen in Hirschsprung’s disease and include young age of onset and symptoms of intestinal obstruction (see Chapter 96). In contrast to functional constipation, affected children do not have symptoms of soiling or evidence of a fecaloma.137 A multicenter study of interobserver variation in the histologic interpretation of findings in children with constipation caused by abnormalities of the enteric nervous system has shown complete agreement in the diagnosis of Hirschsprung’s disease but accord in only 14% of children with colonic motility disorders other than aganglionosis. Some of the clinical features and histologic changes previously associated with congenital hyperganglionosis may be age-related and evolve to normal as children age.135 A diagnosis of congenital hyperganglionosis can be made on the basis of hyperganglionosis of the submucous plexus with giant ganglia and at least one of the following features in rectal biopsy specimens: (1) ectopic ganglia; (2) increased acetylcholinesterase (AChE) activity in the lamina propria; and (3) increased AChE nerve fibers around the submucosal blood vessels. Most patients with congenital hyperganglionosis respond to conservative treatment, including laxatives. Internal anal sphincter myectomy may be performed if conservative management fails.138

Acquired Neuropathies

Chagas’ disease, which results from infection with Trypanosoma cruzi, is the only known infectious neuropathy. The reason for neuronal degeneration in this disorder is unclear but may have an immune basis.139 Patients present with progressively worsening symptoms of constipation and abdominal distention resulting from a segmental megacolon that may be complicated by sigmoid volvulus (see Chapter 109).

Paraneoplastic visceral neuropathy may be associated with malignant tumors outside the gastrointestinal tract, particularly small cell carcinoma of the lung and carcinoid tumors. Pathologic examination of the affected intestine reveals neuronal degeneration or myenteric plexus inflammation.140 An antibody against a component of myenteric neurons has been identified in some patients with this disorder (see Chapter 120).141 Disruption of the ICCs has been associated with a case of small cell lung carcinoma–related paraneoplastic colonic motility disorder.142

MEDICATIONS

Constipation may be a side effect of a drug or preparation taken long term. Drugs commonly implicated are listed in Table 18-4. Common offenders include opioids used for chronic pain, anticholinergic agents including antispasmodics, calcium supplements, some tricyclic antidepressants, phenothiazines used as long-term neuroleptics, and antimuscarinic drugs used for parkinsonism.

PSYCHOLOGICAL DISORDERS

Constipation may be a symptom of a psychiatric disorder or a side effect of its treatment (see Chapter 21). Healthy men who are socially outgoing, energetic, and optimistic—and not anxious—and who described themselves in more favorable terms than others have heavier stools than men without these personality characteristics.143 Psychological factors associated with a prolonged colonic transit time in constipated patients include a highly depressed mood state and frequent control of anger.144 In one study, women with constipation had higher somatization and anxiety scores than healthy controls, and the psychological scores correlated inversely with rectal mucosal blood flow (used as an index of innervation of the distal colon).145 In a study that assessed psychological characteristics of older persons with constipation, a delayed colonic transit time was related significantly to symptoms of somatization, obsessive-compulsiveness, depression, and anxiety.36 In a study of 28 consecutive female patients undergoing psychological assessment for intractable constipation, 60% had evidence of a current affective disorder. One third reported distorted attitudes toward food. Patients with slow-transit constipation reported more psychosocial distress on rating scales than those with normal-transit constipation.146

DEPRESSION

For some patients, constipation can be a somatic manifestation of an affective disorder. In a study of patients with depression, 27% said that constipation developed or became worse at the onset of the depression.147 Constipation can occur in the absence of other typical features of severe depression, such as anorexia or psychomotor retardation with physical inactivity. Psychological factors are likely to influence intestinal function via autonomic efferent neural pathways.145 In an analysis of 4 million discharge records of U.S. military veterans, major depression was associated with constipation, and schizophrenia was associated with both constipation and megacolon.148

EATING DISORDERS

Patients with anorexia nervosa or bulimia often complain of constipation, and a prolonged whole-gut transit time has been demonstrated in patients with these disorders.149 Colonic transit time returns to normal in most patients with anorexia nervosa once they are consuming a balanced diet and gaining weight for at least three weeks.150 Pelvic floor dysfunction is found in some patients with an eating disorder and does not improve with weight gain and a balanced diet.151

Anorexia nervosa should be considered as a possible diagnosis in a young underweight woman who presents with constipation. Patients with an eating disorder often resort to the regular use of laxatives as treatment for constipation or to facilitate weight loss or relieve the presumed consequences of binge eating. Treatment of such patients is directed at the underlying eating disorder (see Chapter 8).

CLINICAL ASSESSMENT

HISTORY

A dietary history should be obtained. The amount of daily fiber and fluid consumed should be assessed. Many patients tend to skip breakfast,152 and this practice may exacerbate constipation, because the postprandial increase in colonic motility is greatest after breakfast.72,153,154 Although caffeinated coffee (150 mg of caffeine) stimulates colonic motility, the ingestion of a meal has a greater effect.155

A detailed social history may provide useful information as to why the patient has sought help for constipation at this point in time; potentially relevant behavioral background information also may be obtained. In patients with IBS, the frequency of a history of sexual abuse is increased as compared with healthy controls.156 In a survey of 120 patients with dyssynergia, 22% reported a history of sexual abuse, and 32% reported a history of physical abuse. Bowel dysfunction adversely affected sexual life in 56% and social life in 76% of patients.157 The physician should be alert to manifestations of depression, such as insomnia, lack of energy, loss of interest in life, loss of confidence, and a sense of hopelessness. A history of physical or sexual abuse may not emerge during the initial visit, but if the physician evinces no surprise at whatever is revealed, indicates that distressing events are common in patients with intestinal symptoms, and maintains a sensitive, encouraging attitude, the full story often gradually emerges during subsequent visits, provided that there is privacy, confidentiality, and adequate time (see Chapters 21 and 118).

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

The rectal examination is paramount in evaluating a patient with constipation. Placing the patient in the left lateral position is most convenient for performing a thorough rectal examination. Painful perianal conditions and rectal mucosal disease should be excluded, and defecatory function should be evaluated. The perineum should be observed both at rest and after the patient strains as if to have a bowel movement. Normally, the perineum descends between 1 and 4 cm during straining. Descent of the perineum with the patient in the left lateral position below the plane of the ischial tuberosities (i.e., >4 cm) usually suggests excessive perineal descent. A lack of descent may indicate the inability to relax the pelvic floor muscles during defecation, whereas excessive perineal descent may indicate descending perineum syndrome. Patients with descending perineum syndrome strain excessively and achieve only incomplete evacuation because of lack of straightening of the anorectal angle. Excessive laxity or descent of the perineum usually results from previous childbirth or excessive straining. Eventually, excessive descent of the perineum may result in injury to the sacral nerves from stretching, a reduction in rectal sensation, and ultimately incontinence resulting from denervation.91 Rectal prolapse may be detected when the patient is asked to strain.

The perianal area should be examined for scars, fistulas, fissures, and external hemorrhoids. A digital rectal examination should be performed to evaluate the patient for the presence of a fecal impaction, anal stricture, and rectal mass. A patulous anal sphincter may suggest prior trauma to the anal sphincter or a neurologic disorder that impairs sphincter function. Other important functions that should be assessed during the digital examination are summarized in Table 18-7. Specifically, the inability to insert the examining finger into the anal canal may suggest an elevated anal sphincter pressure, and tenderness on palpation of the pelvic floor as it traverses the posterior aspect of the rectum may suggest pelvic floor spasm. The degree of descent of the perineum during attempts to strain and expel the examining finger provides another way of assessing the degree of perineal descent. A thorough history and physical examination can exclude most secondary causes of constipation (see Table 18-4).

| History |

DIAGNOSTIC TESTS

TESTS TO EXCLUDE STRUCTURAL DISEASE OF THE INTESTINE

A barium enema study reveals the width and length of the colon and excludes an obstructing lesion severe enough to cause constipation. When fecal impaction is present, a limited enema study with a water-soluble contrast agent outlines the colon and fecal mass without aggravating the condition. A barium examination of the small bowel is indicated only if obstruction or pseudo-obstruction involving the small bowel is suspected (see Chapters 119 and 120). Endoscopy allows direct visualization of the colonic mucosa. The yield of colonoscopy in the absence of “alarm” symptoms in patients with chronic constipation is low and is comparable with that for asymptomatic patients who undergo colonoscopy for colon cancer screening. Therefore, a colonoscopy is recommended only when there has been a recent change in bowel habits, blood in stools, or other alarming symptoms (e.g., weight loss, fever).158,159 All adults older than 50 years who present with constipation should undergo a colonoscopy, flexible sigmoidoscopy and barium enema, or computed tomographic colonography to screen for colorectal cancer, as widely recommended. A flexible sigmoidoscopy is probably sufficient for the evaluation of constipation in patients younger than 50 years without alarm symptoms (e.g., weight loss, recent onset of severe constipation, rectal bleeding) or a family history of colon cancer.

PHYSIOLOGIC MEASUREMENTS

Physiologic testing is unnecessary for most patients with constipation and is reserved for patients with refractory symptoms who do not have an identifiable secondary cause of constipation or in whom a trial of a high-fiber diet and laxatives has not been effective. An American Gastroenterological Association Technical Review on Anorectal Testing Techniques160 has recommended the following investigations in patients with refractory constipation: symptom diaries to establish a diagnosis of constipation and monitor the efficacy of treatment; colonic transit study to confirm the patient’s complaint of constipation and assess colonic motility for slow transit and regional delay; anorectal manometry to exclude Hirschsprung’s disease and to complement other tests of pelvic floor dysfunction; and surface electromyography (EMG) to evaluate anal sphincter function and facilitate biofeedback training. Tests of possible value include the following: defecation proctography to document the patient’s inability to defecate; balloon expulsion test to document the inability to defecate; and rectal sensory testing to help distinguish functional from neurologic disorders as a cause of constipation.

Measurement of Colonic Transit Time

Radiopaque Markers

The normal colonic transit time is less than 72 hours. Measurement of colonic transit time is performed only when objective evidence of slow transit is needed to confirm a patient’s history or as a prelude to surgical treatment. Colonic transit time is measured by performing abdominal radiography 120 hours after the patient has ingested radiopaque markers in a gelatin capsule (Fig. 18-5). Before the study, patients should be maintained on a high-fiber diet and should avoid laxatives, enemas, or medications that may affect bowel function. Retention of more than 20% of the markers at 120 hours is indicative of prolonged colonic transit. Because the markers are eliminated only with defecation, the process of measuring colonic transit is discontinuous, and the result of a transit measurement should be regarded with caution, taking recent defecation into account. If the markers are retained exclusively in the sigmoid colon and rectum, the patient may have a defecatory disorder. The presence of markers throughout the colon, however, does not exclude the possibility of a defecatory disorder because delayed colonic transit can result from a defecatory disorder. Measurements of transit through different segments of the colon are of doubtful value in planning treatment, except for megarectum, in which all the markers move rapidly to the rectum and are retained there.

Wireless Motility Capsule

The wireless pH and pressure recording capsule (SmartPill, Buffalo, NY) is a novel ambulatory technique for assessing colonic transit without radiation. Colonic transit measurements with the wireless capsule technique have been shown to correlate well with the radiopaque marker test and also allow an assessment of gastric and small bowel transit.161

If surgical treatment for severe constipation is being considered (see later), studies of gastric emptying, small bowel transit, and segmental colonic transit times are valuable for confirming slow transit and correlating abnormalities with therapeutic outcome. In particular, scintigraphic studies of gastrointestinal transit are indicated.50 Generally, abnormal gastric or small bowel motility precludes surgical treatment of constipation.

Tests to Assess the Physiology of Defecation

Defecography

Defecography is performed by instilling thickened barium into the rectum. With the patient sitting on a radiolucent commode, films or videos are taken during fluoroscopy with the patient resting, deferring defecation, and straining to defecate. This procedure evaluates the rate and completeness of rectal emptying, anorectal angle, and amount of perineal descent. In addition, defecography can identify structural abnormalities, such as a large rectocele, internal mucosal prolapse, or intussusception. A rectocele represents a herniation, usually of the anterior rectal wall into the lumen of the vagina, and usually results from trauma during childbirth or an episiotomy.161 Paradoxical anal sphincter contraction is common in patients with a rectocele, suggesting that straining and attempts at emptying against a contracted pelvic floor may facilitate development of a rectocele. The limitations of defecography include variability among radiologists in interpreting studies, inhibition of normal rectal emptying because of patient embarrassment, and differences in texture between barium paste and stool. Confirmatory studies are needed before a decision about management can be made on the basis of the radiographic findings alone. Importantly, identified anatomic abnormalities are not always functionally relevant. For example, a rectocele is only relevant if it fills preferentially (i.e., instead of the rectal ampulla) and fails to empty after simulated defecation. Magnetic resonance defecography may offer advantages over standard barium defecography162 but is not yet widely available.

Balloon Expulsion Test

When the rectum is distended with a balloon, the internal anal sphincter relaxes. The inability to evacuate a 50- to 60-mL inflated balloon in the rectum163 while sitting on the toilet for two minutes, with the addition of 200 g of weight to the end of the balloon,93 suggests a defecatory disorder. The balloon expulsion test is an effective and useful screening tool for identifying patients with a defecatory disorder who do not have pelvic floor dyssynergia. In one study of 359 patients with constipation, the balloon expulsion test was abnormal in 21 of 24 patients with pelvic floor dyssynergia and an additional 12 of 106 patients without pelvic floor dyssynergia. (The diagnosis of pelvic floor dyssynergia was confirmed by manometric and defecographic findings according to the Rome II criteria.164)

Anorectal Manometry

Anorectal manometry can provide useful information about patients with severe constipation by assessing the resting and maximum squeeze pressure of the anal sphincters, presence or absence of relaxation of the anal sphincter during balloon distention of the rectum (rectoanal inhibitory reflex), rectal sensation, and ability of the anal sphincter to relax during straining.93,158,165 Patients with a defecatory disorder commonly have inappropriate contraction of the anal sphincter when they bear down. The absence of the rectoanal inhibitory reflex raises the possibility of Hirschsprung’s disease. A high resting anal pressure suggests the presence of an anal fissure or anismus, the paradoxical contraction of the external anal sphincter in response to straining or pressure within the anal canal. Rectal hyposensitivity suggests a neurologic disorder; however, the volume of rectal content needed to induce rectal urgency also may be increased in patients with fecal retention, and the results of rectal sensitivity testing need to be interpreted with caution.

Rectal Sensitivity and Sensation Testing

Rectal sensitivity to distention can be measured by introducing successive volumes of air into a rectal balloon and recording the volume at which the stimulus is first perceived, the volume that produces an urge to defecate, and the volume above which further addition of air can no longer be tolerated owing to discomfort. These measurements are not of value in the routine investigation of constipation but are of research interest. The threshold current needed to elicit sensation when the rectal mucosa is stimulated electrically by a current passed between bipolar electrodes can be used as a test of sensory nerve function, but the test has not been established for general use.93

TREATMENT

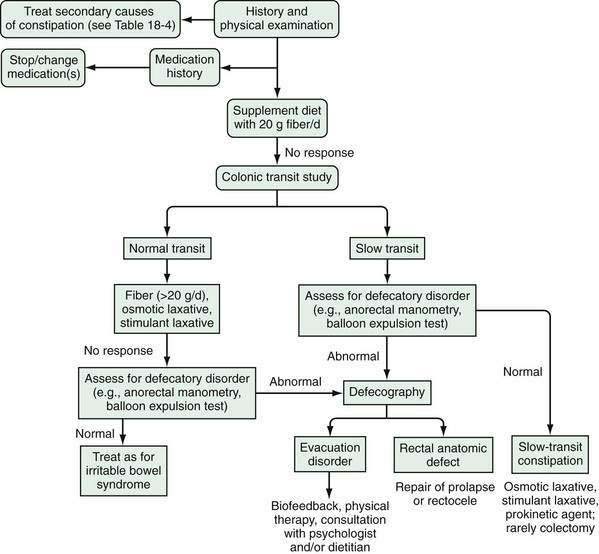

Initial treatment of constipation is based on nonpharmacologic interventions. If these measures fail, then pharmacologic agents may be used. Figure 18-6 provides an algorithm for the evaluation and treatment of patients with severe constipation. If a defecatory disorder is present, initial treatment should include biofeedback; up to 75% of patients with disordered evacuation respond to biofeedback, and many do not respond well to fiber supplementation or oral laxatives. Otherwise, the initial treatment should include increased fluid, exercise, and intake of fiber, either through changes in diet or use of commercial fiber supplements. Patients who do not improve with fiber should be given an osmotic laxative, such as milk of magnesia or polyethylene glycol. The dose of the osmotic laxative should be adjusted until soft stools are attained. Stimulant agents, such as bisacodyl or senna derivatives, should be reserved for patients who do not respond to fiber or osmotic laxatives.

GENERAL MEASURES

Psychological Support

Constipation may be aggravated by stress or may be a manifestation of emotional disturbance (e.g., previous sexual abuse; see Chapter 21). For such patients, an assessment of the person’s circumstances, personality, and background and supportive advice may help more than any physical measures of treatment. Behavioral treatment (see later) offers a physical approach with a psychological component and is often acceptable and beneficial. Psychological treatment is needed only when it would be indicated in any circumstance, not specifically for constipation.

Fluid Intake

Dehydration or salt depletion is likely to lead to increased salt and water absorption by the colon, leading in turn to the passage of small hard stools. Although dehydration is generally accepted as a risk factor for constipation, unless a person is clinically dehydrated, no data support the notion that increasing fluid intake improves constipation.166

Dietary Changes and Fiber Supplementation

After studying the dietary and stool patterns of rural Africans in the early 1970s, Burkitt and colleagues speculated that a deficiency in dietary fiber was contributing to constipation and other colonic diseases in Western societies.167 Since then, studies have shown that when nonconstipated persons increase their intake of dietary fiber, stool weight increases in proportion to their baseline stool weight and frequency of defecation and correlates with a decrease in colonic transit time.168 Every gram of wheat fiber ingested yields approximately 2.7 g of stool expelled. It follows that when an increased intake of dietary fiber leads to an increase in stool weight in constipated subjects who pass small stools, the resulting stool weight may still be lower than normal. For this reason, the therapeutic results of a high-fiber diet are often disappointing as a treatment for constipation. In a study of 10 constipated women who took a supplement of wheat bran, 20 g/day, average daily stool weight increased from approximately 30 to 60 g/day, with only half of patients achieving a normal average stool weight. Bowel frequency increased from a mean of two to three bowel movements weekly.169 In a controlled, crossover trial, 24 patients took 20 g of bran or placebo daily for four weeks. Although bran was more effective than placebo in improving bowel frequency and oroanal transit rate, the occurrence and severity of constipation experienced by the patients did not differ between the two treatment periods.170 This result probably reflects the observation that patients complain mainly of difficulty in defecation, rather than a decreased frequency of bowel movements. In a series of constipated patients, about half were reported to have gained some benefit from a bran supplement of 20 g daily.171

Dietary fiber appears to be effective in relieving mild to moderate43 but not severe constipation,69 especially if severe constipation is associated with slow colonic transit, evacuation disorders, or medications. Although dietary modification may not succeed, all constipated subjects should be advised initially to increase their dietary fiber intake as the simplest, most physiologic, and cheapest form of treatment. Patients should be encouraged to take about 25 g of NSPs daily by eating whole-wheat bread, unrefined cereals, plenty of fruit and vegetables and, if necessary, a supplement of raw bran, either in breakfast cereals or with cooked foods. Specific dietary counseling often is needed to achieve a satisfactory increase in dietary fiber.

Because of side effects, adherence with fiber supplementation is poor, especially during the first several weeks of therapy. Side effects include abdominal distention, bloating, flatulence, and poor taste. Most controlled studies of the effect of fiber have shown that the minimum supplementation needed to consistently alter bowel function or colonic transit time significantly is 12 g/day. To improve adherence, patients should be instructed to increase their dietary fiber intake gradually over several weeks to approximately 20 to 25 g/day. If results of therapy are disappointing, commercially packaged fiber supplements should be tried (Table 18-8). Fiber and bulking agents are concentrated forms of NSPs based on wheat, plant seed mucilage (ispaghula), plant gums (sterculia), or synthetic methylcellulose derivatives (methylcellulose, carboxymethylcellulose; see later).

| AGENT | STARTING DAILY DOSE (G) | COMMENTS |

|---|---|---|

| Methylcellulose | 4-6 | Semisynthetic cellulose fiber that is relatively resistant to colonic bacterial degradation and tends to cause less bloating and flatus than psyllium |

| Psyllium | 4-6 | Made from ground seed husk of the ispaghula plant; forms a gel when mixed with water, so an ample amount of water should be taken with psyllium to avoid intestinal obstruction; undergoes bacterial degradation, which may contribute to side effects of bloating and flatus; allergic reactions such as anaphylaxis and asthma have been reported but are rare |

| Polycarbophil | 4-6 | Synthetic fiber made of polymer of acrylic acid, which is resistant to bacterial degradation |

| Guar gum | 3-6 | Soluble fiber extracted from seeds of the leguminous shrub Cyamopsis tetragonoloba |

SPECIFIC THERAPEUTIC AGENTS

Commercial Fiber Products

Methylcellulose

Methylcellulose is a semisynthetic NSP of varying chain length and degree of methylation. Methylation reduces bacterial degradation in the colon. One study of constipated patients with an average daily fecal weight of only 35 g showed an increase in fecal solids with 1, 2, and 4 g of methylcellulose/day, but fecal water increased only with the 4-g dose. Bowel frequency in this group of patients increased from an average of two to four stools weekly, but the patients did not report marked improvement in consistency or ease of passage of stools (see Table 18-8).172

Ispaghula (Psyllium)

Ispaghula (3.4 g as Metamucil) has been shown to increase fecal bulk to the same extent as methylcellulose 1 to 4 g daily in constipated subjects. Although both stool dry and wet weights increased, the total weekly weights remained less than those of a healthy control group without treatment. In an observational study, 149 patients were treated with psyllium in the form of Plantago ovata seeds, 15 to 30 g daily, for a period of at least 6 weeks. The response to treatment was poor among patients with slow colonic transit or a disorder of defecation, whereas 85% of patients without abnormal physiologic testing results improved or became symptom-free. Nevertheless, the authors recommend that a trial of dietary fiber be undertaken before diagnostic testing is performed.69

Ispaghula taken by mouth can cause an acute allergic immunoglobulin E–mediated response, with facial swelling, urticaria, tightness in the throat, cough, and asthma.173 Workers who inhale the compound during manufacture or preparation can have a similar reaction174 (see Table 18-8).

Calcium Polycarbophil

Calcium polycarbophil is a hydrophilic polyacrylic resin that is resistant to bacterial degradation and thus may be less likely to cause gas and bloating. In patients with IBS, calcium polycarbophil appears to improve global symptoms and ease of stool passage175 but not abdominal pain (see Table 18-8).

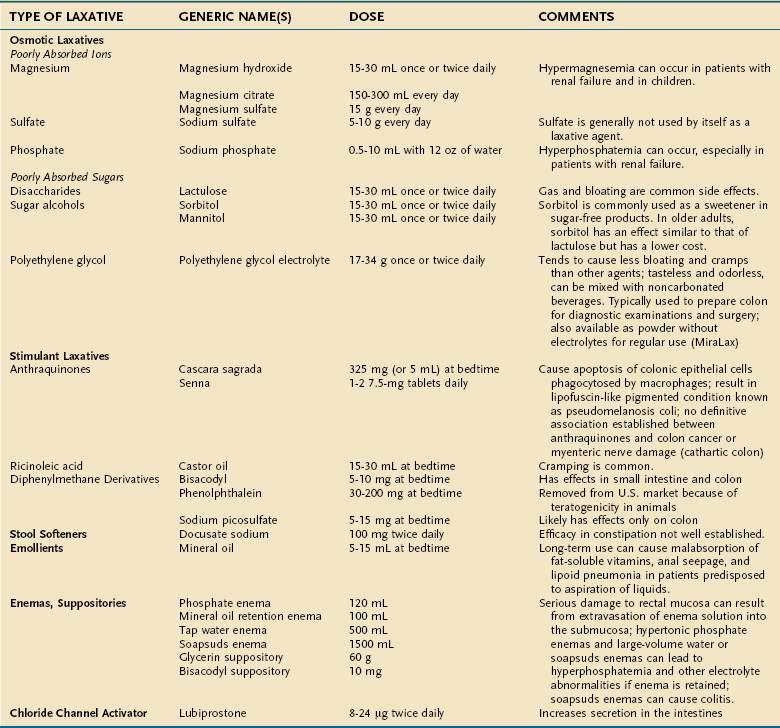

Other Laxatives

The main groups of laxatives other than fiber are osmotic agents and stimulatory laxatives; stool softeners and emollients are additional therapeutic agents (see later) (Tables 18-9 and 18-10).

Table 18-10 Grade of Evidence for the Use of Laxatives According to the American College of Gastroenterology Task Force on Chronic Constipation

| LAXATIVE | GRADE OF EVIDENCE* |

|---|---|

| Bulking agents | |

| Psyllium | B |

| Calcium polycarbophil | B |

| Bran | † |

| Stool softeners | B |

| Lubricants | C |

| Osmotic laxatives | |

| PEG | A |

| Lactulose | A |

| Milk of magnesia | † |

| Stimulant laxatives | B |

| Prokinetic agent | |

| Tegaserod‡ | A |

| Chloride channel activator | |

| Lubiprostone | § |

PEG, polyethylene glycol.

* Grade A: Based on two or more randomized controlled trials (RCTs) with adequate sample sizes and appropriate methodology. Grade B: Based on evidence from a single RCT of high quality or conflicting results from high-quality RCTs or two or more RCTs of lesser quality. Grade C: Based on noncontrolled trials or case reports.

‡ Removed from the U.S. market.

Data from Brandt LJ, Prather CM, Quigley EM, et al. Systematic review on the management of chronic constipation in North America. Am J Gastroenterol 2005; 100(Suppl 1):S5-21.

Poorly Absorbed Ions