Constipation

Perspective

In the ED, the complaint of constipation should be of concern when it represents a significant change from a patient’s own normal pattern that is creating discomfort for the patient. This change may manifest as a decrease in frequency of defecation, sudden and persistent change in the character or amount of stools (especially decrease in stool caliber), blood in the stool, or problems expelling the stool.1

Epidemiology

The prevalence of constipation varies worldwide. In North America the prevalence is approximately 16%.2 In adults, constipation is more common in women, the elderly, those with high body mass index, and those with low socioeconomic status.2 A consistent trend of increasing prevalence of constipation is observed with age, with significant increases after the age of 70 years. The high prevalence among elderly patients is multifactorial and related to a diet low in fiber, sedentary habits, multiple medications, and various disease processes that impair neurologic and motor control.

Pathophysiology

Normally the gastrointestinal tract is presented with 9 to 10 L/day of secretions and ingested fluids. The small intestine usually absorbs all of this except for approximately 500 mL. The colon mixes the ileal effluent, ferments and salvages the unabsorbed carbohydrate residues, and desiccates the contents to form stool. The process of stool transport and evacuation is complex and is regulated by neurotransmitters, intrinsic colonic reflexes, and a multitude of learned and reflex mechanisms that are not fully understood. Constipation may result from structural, metabolic, mechanical, neurologic, or behavioral disorders that affect the colon or anorectum either directly or indirectly.3–5

Diagnostic Approach

The causes of constipation are numerous. Causes of constipation can be divided into primary (no apparent external cause) and secondary causes (summarized in Box 32-1). These two groupings have some overlap. In the ED, patients most commonly have acute constipation resulting from side effects of medications or avoidance of defecation secondary to presence of painful perianal lesions such as fissures, hemorrhoids, or perirectal abscesses.

Pivotal Findings

A thorough, detailed history usually identifies the most likely cause of the patient’s constipation. Defining what the patient means by “constipation” is a good starting point. Essential information includes the presence or absence of signs or symptoms that the American College of Gastroenterology terms “alarm symptoms.” These include fever, anorexia, nausea, vomiting, blood in the stool, anemia, weight loss of more than 10 lb, a family history of colon cancer, onset of constipation after the age of 50, and acute onset of constipation in an elderly patient.1

Physical Examination

The anorectal examination and an evaluation of the stool are important parts of the physical assessment. Anorectal inspection may reveal fissures, hemorrhoids, or rectal prolapse. The digital rectal examination should include palpation for masses, and the presence or absence of pain should be noted. Other possible findings include strictures, high sphincter tone, and the presence of blood. Having the patient bear down may be helpful in assessing sphincter function and may reveal milder forms of prolapse. The quantity and the characteristics of the stool should be recorded. Testing the stool for occult blood may yield additional information, although straining with stooling can produce local anal lesions and bleeding. If results of occult blood testing are positive, diverticular disease, carcinoma, and trauma from repeated attempts at straining all are possibilities. Results of rectal examination have not been shown, however, to correlate with complaints of constipation or with evidence of colonic loading on abdominal radiographs. The rectal examination alone should not be used to confirm or exclude the presence of constipation.4

Ancillary Testing

The majority of patients who visit the ED with a chief complaint of constipation do not need any testing. Plain abdominal radiographs may provide information about extent of stool retention but also may suggest emergent diagnoses such as megacolon or volvulus. Although constipation can cause cramping and abdominal pain, plain radiographs documenting an increased stool load in the constipated patient should not be used to rule out more serious underlying causative disorders, especially if the patient has a significant amount of abdominal pain or tenderness on examination. Also, several studies have shown that interpretation of abdominal films in the evaluation of constipation is highly variable and subjective.6,7

Patients with acute constipation for which the cause is not readily apparent should receive symptomatic treatment, with referral for outpatient evaluation and reassessment as needed. The patient in the ED with chronic constipation and no alarming signs or symptoms should receive empirical treatment without any ancillary testing. Outpatient tests may eventually include blood tests to investigate metabolic or endocrine causes and possibly specialized tests such as colonic transit studies and anorectal manometry. Consensus recommendations state that the routine use of colonoscopy to exclude organic disorders in patients with chronic constipation symptoms is not indicated, although it is still recommended for colon cancer screening in all patients older than 50 years.3–5

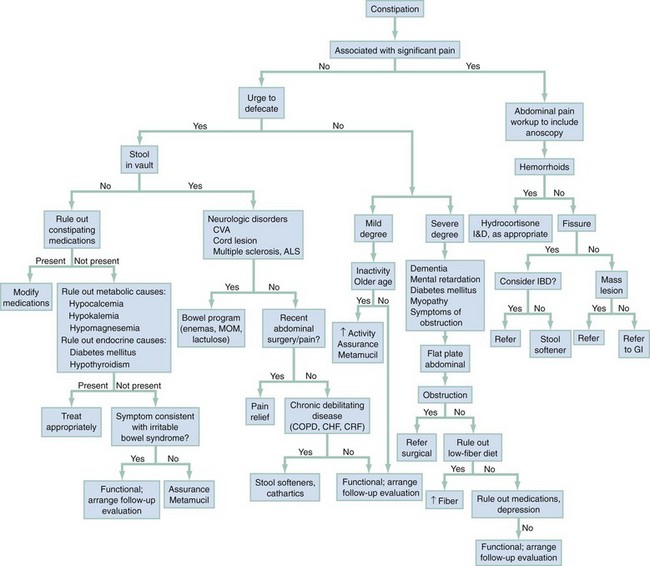

Diagnostic Algorithm

Figure 32-1 presents a diagnostic algorithm. If the physical examination reveals a structural or mechanical cause, such as pain from hemorrhoids, fissures, or mass lesion, the appropriate treatment or referral is indicated; the constipation will resolve once the cause is addressed. If no obvious cause is found on examination, then determination of the presence or absence of stool in the rectal vault may be helpful. History will be very helpful in differentiating among causes such as medication side effect and possible neurologic disease.

Empirical Management

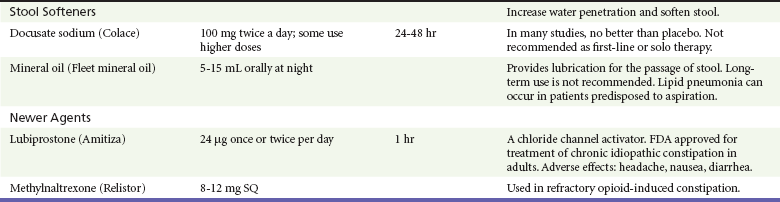

Treatment of acute constipation is directed toward eradicating the underlying cause and providing symptom relief. Prevention of further episodes of constipation may include recommending increased fluid intake, increased exercise, increased dietary fiber, and, if necessary, additional sources of bulk in the form of synthetic bulk agents. These interventions will not usually help the acutely constipated patient in the short term. Therapeutic choices and recommendations for patients should be customized based on patient preferences as well as history of efficacy of treatments used in the past. See Box 32-2 for further details. Specific recommendations may also include withholding a causal medication, management of an anal fissure, or draining of a perirectal abscess. Stool softeners (e.g., docusate sodium), although commonly recommended to patients, should not be used as a first-line agent for most patients with constipation. Docusate has not been shown to be any more effective than placebo in relieving acute constipation, although it may be somewhat helpful in patients with anal fissures or hemorrhoids, which can make defecation painful.

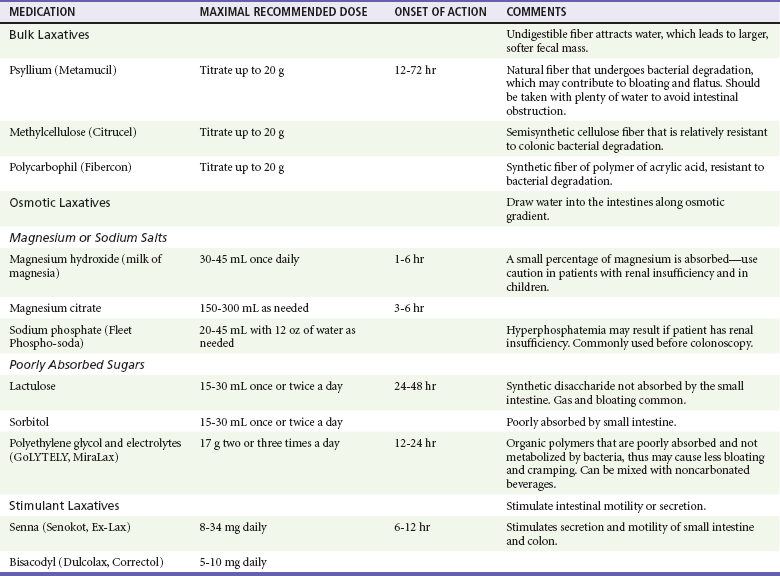

Specific agents for symptomatic treatment of constipation are listed in Table 32-1. There are five classes of commonly used laxatives. These are bulking agents, osmotic salts, poorly absorbed sugars, stool softeners, and stimulant laxatives. These agents aid defecation by decreasing stool consistency and/or by stimulating colon motility.8 There are also several new pharmacologic classes being used or investigated for the treatment of constipation in specific groups of patients.

A group of patients that often experiences constipation are those who are on chronic, medically necessary medications that cause constipation (e.g., opioids in patients with chronic pain or cancer). These patients should be on bowel regimens designed to prevent constipation. These regimens usually include such measures as high levels of dietary fiber (e.g., added prunes or figs) as well as daily administration of stimulant laxatives.9 A recent advance in the treatment of refractory opioid-induced constipation is methylnaltrexone (Relistor). Methylnaltrexone is a specific peripheral mu opioid receptor antagonist and is administered subcutaneously. It selectively blocks the gastrointestinal mu opioid receptors without compromising central mediated effects of opioid analgesia or precipitating withdrawal. Its use in palliative care patients was recently supported in a Cochrane review.10

There are alternatives to the traditional laxatives and enemas for patients with chronic constipation. Patients with recalcitrant constipation may benefit from interventions such as biofeedback and bowel training.5

References

1. American College of Gastroenterology Chronic Constipation Task Force. An evidence-based approach to the management of chronic constipation in North America. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:S1.

2. Mugie, SM, Benninga, MA, Di Lorenzo, C. Epidemiology of constipation in children and adults: A systematic review. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2011;25:3.

3. Salles, N. Basic mechanisms of the aging gastrointestinal tract. Dig Dis. 2007;25:1127.

4. Bouras, E, Tangaloas, E. Chronic constipation in the elderly. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2009;38:463.

5. Chatoor, D, Emmanuel, A. Constipation and evacuation disorders. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2009;23:517.

6. Moylan, S, et al. Are abdominal x-rays a reliable way to assess for constipation? J Urol. 2010;184:1692.

7. Jackson, CR, Lee, RE, Wylie, AB, Adams, C, Jaffray, B. Diagnostic accuracy of the Barr and Blethyn radiological scoring systems for childhood constipation assessed using colonic transit time as the gold standard. Pediatr Radiol. 2009;29:664.

8. Singh, S, Rao, SS. Pharmacologic management of chronic constipation. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2010;29:509.

9. Librach, SL, et al. Consensus recommendations for the management of constipation in patients with advanced, progressive illness. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2010;40:761.

10. Candy, B, Jones, L, Goodman, ML, Drake, R, Tookman, A. Laxatives or methylnaltrexone for the management of constipation in palliative care patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 19, 2011.