11 Constipation

Case

A 33-year-old female accountant consults because of worsening constipation. She describes on specific questioning passing a bowel movement every 2 days. She strains excessively to pass the bowel movement, and the stools feel hard. She has a sensation of incomplete emptying after she has a bowel movement, and she finds this troubling. Occasionally, she will press around the anal area to help hard stool evacuate. She remembers being constipated as a child and all her life. She has not seen any mucus or blood in the stools, and she has no history of weight loss, vomiting or any alarm symptoms. She describes mild abdominal discomfort at times; this is usually present before she passes stools, but she denies pain relief with defecation or a change in her stools when pain begins. She has been regulating her bowels by taking over-the-counter laxatives, but has found that these have not been very helpful. She never has diarrhoeal symptoms.

Introduction

Constipation is often dismissed as a minor symptom by doctors, although for some patients it can be the source of considerable anxiety and disability, and is frequently associated with general malaise and a sense of poor health. A list of the causes of chronic constipation is presented in Box 11.1. While the majority of patients who complain of constipation have a benign disorder of colorectal function associated with faulty diet, drugs or bowel habit, called simple constipation, it should always be remembered that constipation may be the presenting symptom of a serious colonic disorder, such as carcinoma, or a generalised metabolic disorder, such as hypothyroidism or hypercalcaemia. Chronic constipation can occur in the absence of structural or metabolic disorders because of abnormally slow colonic transit (slow transit constipation), obstructed defecation (pelvic floor dysfunction), or both. The irritable bowel syndrome, characterised by abdominal pain and a variable bowel habit, is also an important cause of constipation (Ch 7). A careful history and examination to ascertain the likely mechanism producing constipation allows investigations to be correctly chosen, which in turn should determine management.

Clinical Approach to Patients with Constipation

History

Constipation may be induced by certain drugs, such as narcotics, antihypertensives or antidepressants. Thus, it is very important to ask about the use of drugs and whether their introduction corresponded to recent alterations in bowel habit. A lack of dietary fibre is a common cause of constipation and a full dietary history should be taken. Slow transit constipation, and occasionally simple constipation, may run in families and a history of other family members being similarly affected may provide useful information.

Physical examination

A rectal examination is important. The perineum should be inspected for painful anal fissures, fistulae, abscesses or local neoplasm. The patient should be asked to bear down to demonstrate perineal descent due to pelvic floor weakness, haemorrhoidal prolapse or the formation in women of a rectocoele or uterine prolapse. Occasionally, rectal mucosal or full-thickness prolapse may be seen (Ch 22). An anal fissure will be very painful on trying to put your finger in the anal canal. Obvious fistula suggests Crohn’s disease. A rectal examination can detect if there is any evidence of anal canal stenosis. An obvious rectal mass may represent a cancer. Obvious faecal impaction may be present in very severe constipation, particularly in the elderly. To complete the rectal examination, the patient should be asked to try to push the examiner’s finger out by straining. If the puborectalis and anal sphincter contract and increase pressure in the anal canal rather than relaxing to widen the canal, this suggests (but is not diagnostic of) pelvic outlet obstruction. Next, turn your finger to the anterior position. Try to feel if there is any evidence of a rectocoele, which pushes through the anterior rectal wall when straining. Sigmoidoscopy should be performed if adequate rectal emptying can be achieved.

Investigations

Generally, types of constipation can be divided into those with no apparent structural abnormality of the anus, rectum or colon and those with recognised structural disease such as cancer, a stricture or megacolon. A third group of patients have generalised metabolic, neurological or endocrine diseases, which may produce constipation as a secondary event (Box 11.1).

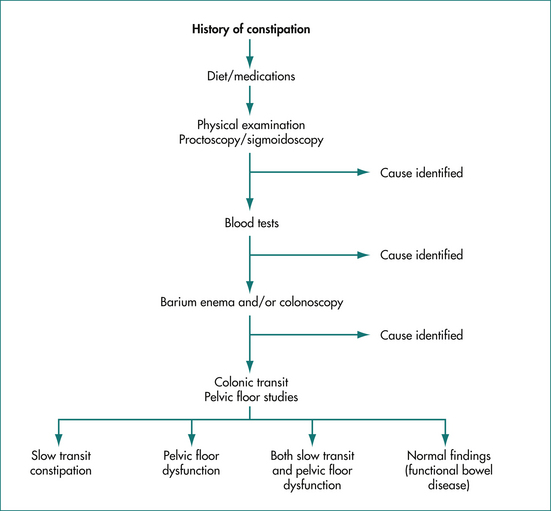

The extent of investigations for the individual patient with constipation depends very much on the clinical assessment (Fig 11.1). In young patients in whom suspicion of serious underlying disease such as colon cancer is low, a trial of therapy without investigation is reasonable. In most other patients it is logical to first assess that the colon is structurally normal. In those patients who do not respond to initial simple therapy, further investigations may be necessary.

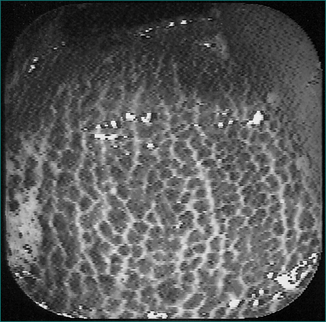

Colonoscopy

Colonoscopy is the test of choice to exclude significant structural colonic disease. It is an alternative to sigmoidoscopy and barium enema. Melanosis coli may be evident in patients who use laxatives regularly (Fig 11.2). Colonic stricture and neoplasm can usually be effectively diagnosed by this technique.

Radiology

Virtual colonoscopy (CT colonoscopy) is a radiological technique that provides a three-dimensional reconstruction of the colon; it can accurately detect large colonic polyps (1 cm and over) or cancer. A bowel preparation is required. Extra colonic findings are seen commonly; one in 10 is sent for additional testing but this is of little benefit in the majority.

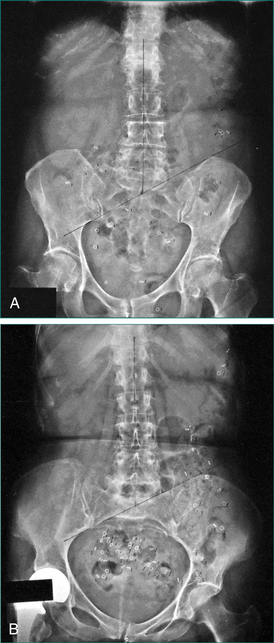

Colonic transit studies

One clinically useful quantitative test is to give 24 radio-opaque markers by mouth on 3 consecutive days and obtain a plain abdominal x-ray examination on day 4; the number of markers is counted to calculate total and regional colonic transit times (Fig 11.3A and B). A transit time of 70 hours or longer is abnormally slow. Laxatives should be stopped 2 days prior to the test and a high-fibre diet should be continued throughout. Patients should be off opioid painkillers.

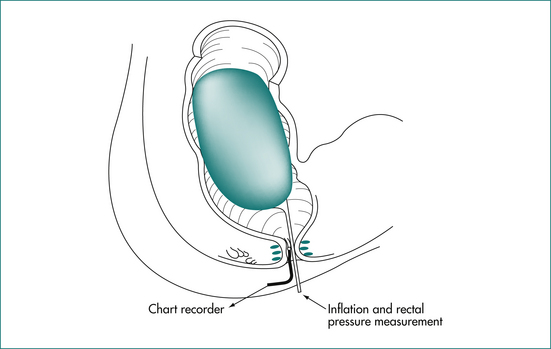

Ano-rectal manometry, sensation and balloon expulsion

Pressure within the anal canal may be recorded by perfused tubes, microballoons, or strain-gauge transducers (see Ch 16). Resting anal tone and the response to voluntary contraction and straining at defecation give useful information about the state of the pelvic floor muscles.

The recto-sphincteric reflex may be elicited by rectal distension with simultaneous recording of anal pressure. A positive reflex consists of a relaxation of the internal anal sphincter (lowered resting anal tone) following rectal distension (Fig 11.4). The reflex is mediated by the myenteric plexus and is characteristically absent in those with Hirschsprung’s disease (because of congenital aganglionosis).

Dynamic proctography

Video radiographic recording of defecation with contrast material in the rectum (by a defecating proctogram or magnetic resonance imaging) will demonstrate perineal descent, rectal intussusception and paradoxical sphincter contraction in some patients with obstructed defecation (Ch 16).

Motility studies

Small bowel motility can be measured by placing a manometric assembly through the mouth in the upper small intestine. Chronic intestinal pseudo-obstruction, a rare but important cause of slow transit constipation, can be diagnosed by this test (Ch 7). Recording of colonic motility is a research tool and is not routinely used to base diagnosis and management.

Rectal biopsy

In rare cases where the history, x-ray findings and results of physiological studies suggest the possibility of Hirschsprung’s disease, a rectal biopsy is usually necessary for confirmation. Traditionally, this has been of the full-thickness type, requiring general anaesthesia. More recently, suction biopsies with special stains have been shown to be useful, especially in children.

Approach to Management

Therapeutic agents

Therapeutic agents available for the treatment of constipation are listed in Table 11.1.

Table 11.1 Thrapeutic agents in constipation and major side effects

| Agents | Side effects |

|---|---|

| Hydrophilic bulk-forming agents | |

| Psyllium mucilloid, sterculia, ispaghula, methylcellulose, unprocessed bran | Inadequate fluid intake may result in intestinal obstruction |

| Osmotic laxatives | |

| Polyethylene glycol, magnesium sulfate/hydroxide, mannitol, lactulose, sodium salts | May cause electrolyte imbalance |

| Stimulant laxatives | |

| Bisacodyl, senna, cascara, danthron | Damage to the myenteric plexus with prolonged use now appears very rare after the withdrawal of phenolphthalein |

| Stool-softening agents | |

| Paraffin oil, dioctyl-sodium sulfosuccinate | May cause mineral oil aspiration and pneumonia |

| Per rectum evacuants | |

| Glycerine suppositories, phosphate enemas | May cause rectal or anal sphincter damage if incorrectly used |

Hydrophilic bulk-forming agents

These agents bind water, increase stool weight and act as a substrate for colonic bacteria. Increased intake in constipated patients usually results in larger stools and reduced colonic transit time. Small bowel absorption of other substances (e.g. zinc, iron, glucose and bile salts) may be affected, but this is rarely of clinical significance. It should be remembered that severely constipated patients sometimes do not respond to these agents. In some cases, symptoms may be made worse because of the increased flatus produced. Patients with slow transit constipation generally do not respond to fibre (and may get worse).

Surgical Treatment

Colectomy

Surgical therapy should be regarded as a measure of last resort in patients with very severe constipation and documented slow colonic transit without other disease. The surgical procedure of choice in slow transit constipation is subtotal colectomy with ileorectal anastomosis. Extensive resection is required as lesser resection is usually associated with recurrence of constipation. The procedure should be done only in centres of excellence.

Clinical Approach to Specific Types of Constipation

Hospitalised patients

Constipation in hospital is usually multifactorial. If a patient has not passed stool for 2 days, and no clearcut cause is apparent, bisacodyl (10 mg at night) or magnesium hydroxide (in the morning) is reasonable first-line therapy.

Megacolon

Those with non-Hirschsprung’s or idiopathic megacolon may be subdivided into patients whose symptoms develop in childhood and patients whose symptoms develop in later life. In the former group, faecal impaction and soiling are usually the presenting symptoms. The initial step is to disimpact the rectum as described above and then maintain the patient on regular oral laxatives. Encouragement regarding regular defecation is important. Sometimes regular per-rectum evacuants are needed to maintain an empty rectum.

Key Points

Brandt L.J., Prather C.M., Quigley E.M., et al. Systematic review on the management of chronic constipation in North America. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100(suppl 1):S5-S21.

Di Palma J.A., Smith J.R., Cleveland M. Overnight efficacy of polyethylene glycol laxative. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:1776-1779.

Emison E.S., McCallion A.S., Kashuk C.S., et al. A common sex-dependent mutation in a RET enhancer underlies Hirschsprung disease risk. Nature. 2005;434:857-863.

Jones M.P., Talley N.J., Nuyts G., et al. Lack of objective evidence of efficacy of laxatives in chronic constipation. Dig Dis Sci. 2002;47:2222-2230.

Lembo A., Camilleri M. Chronic constipation. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:1360-1368.

Muller-Lissner S.A., Kamm M.A., Scarpignato C., et al. Myths and misconceptions about chronic constipation. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:232-242.

Ramkumar D., Rao S.S. Efficacy and safety of traditional medical therapies for chronic constipation: systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:936-971.

Rao S.S., Ozturk R., Laine L. Clinical utility of diagnostic tests for constipation in adults: a systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:1605-1615.

Talley N.J. Management of chronic constipation. Rev Gastroenterol Disord. 2004;4:18-24.

Talley N.J., Jones M., Nuyts G., et al. Risk factors for chronic constipation based on a general practice sample. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:1107-1111.

Talley N.J., Lasch K.L., Baum C.L. A gap in our understanding: chronic constipation and its comorbid conditions. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:9-19.

Thomas J., Karver S., Cooney E.A., et al. Methylnattrexone for opioid-induced constipation in advanced illness. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2332-2343.