Conjunctivochalasis

Introduction

Conjunctivochalasis (CCh) is a characteristically bilateral condition where redundant, nonedematous conjunctiva causes a spectrum of clinical findings ranging from exacerbation of an unstable tear film to mechanical disruption of tear flow. The origination of the term conjunctivochalasis came from W. L. Hughes in 1942; however, descriptions of this same entity were noted as early as 1908 by Elschnig and by Braunschweig and Wollenberg in 1921 and 1922, respectively.1 They described the more severe spectrum of findings in CCh of subconjunctival hemorrhage, pain, and exposure keratopathy. Later work described the more mild symptomatology of CCh, including dry eye to the more moderate symptoms of excess lacrimation by impeding tear clearance.2

Because CCh can be asymptomatic, it is often overlooked as a normal variant of aging. However, it is an important clinical diagnosis that must be considered in the evaluation of patients with ocular irritation and tearing. CCh typically presents as loose inferior conjunctiva, that disrupts the inferior tear meniscus; however, it is thought to also involve the superior conjunctiva in some cases.3,4 Aside from the most common symptoms of irritation and lacrimation, other associated complaints include blurred vision, discharge, dryness, ocular fatigue, subconjunctival hemorrhage, and eye stiffness on awakening.5 The severity of CCh symptoms tends to worsen with both downgaze and digital pressure.

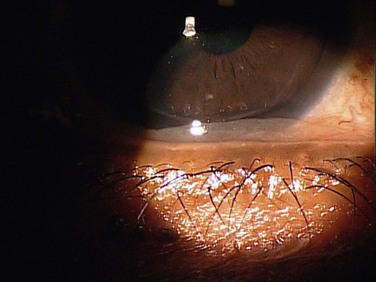

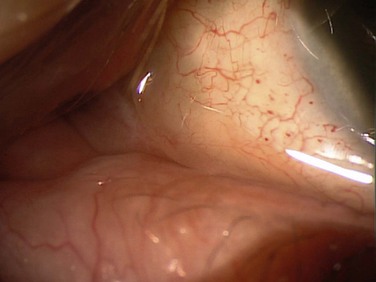

Slit lamp biomicroscopy can show prolapse of the conjunctiva over the lower lid margin in the temporal, medial or nasal regions, or any combination of these regions (Fig. 20.1). This conjunctival prolapse can impede tear outflow through the inferior punctum, resulting in epiphora. Mechanical trauma can also cause recurrent subconjunctival hemorrhage in this sector (Fig. 20.2).

Epidemiology

Conjunctivochalasis has been identified to be an age-dependent phenomenon by several studies.4,6–8 It has been seen in patients as early as the first decade of life and tends to increase in prevalence and severity with age. The Zhang study estimated the prevalence to be 44.08% in a senile Chinese population, while Mimura noted an even higher prevalence in a hospital-based Japanese population. There was no increase in grade of severity of CCh based on gender in Mimura’s study. The location of CCh is most frequently found in the nasal and temporal regions of inferior conjunctiva, versus middle zone of inferior conjunctiva or superior conjunctiva.4,7,8 Conjunctivochalasis has also been noted to be more frequent in patients with thyroid disease and with contact lens wear.6,9

Pathophysiology

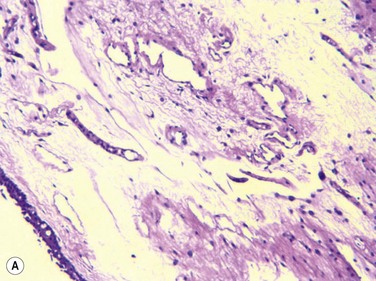

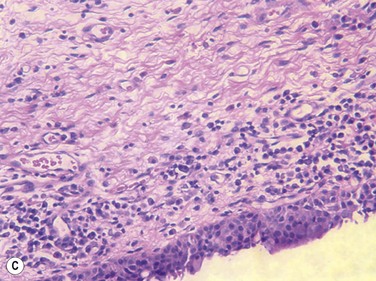

Francis et al., in a prospective clinical and histopathological study of 29 CCh patients, showed that 22 of 29 specimens displayed normal conjunctival histology, while only four specimens showed inflammatory changes and three specimens showed elastosis (Fig. 20.3).10 They hypothesized, based on these results, that the pathogenesis of CCh is therefore, multifactorial, including local trauma, ultraviolet radiation and delayed tear clearance as inciting factors. Watanabe et al. demonstrated microscopic lymphangiectasia of the subconjunctiva in 39 of 44 specimens taken from patients with severe CCh, with no evidence of inflammation.11 They also noted loss of typical fiber patterns with fragmented elastic fibers and sparse assemblages of collagen fibers in all 44 specimens. Their conclusion was that mechanical forces between the lower eyelid and conjunctiva gradually impaired lymphatic flow, resulting in lymphatic dilation and clinical CCh. Immunostaining by Yokoi et al. supported the negligible role of inflammation in CCh, by comparing conjunctival samples in CCh patients to those of known normal and known inflammatory ocular surface disease.5

Although there is little histopathologic support of inflammation playing a role in CCh, mechanistic evidence suggests a shift in the normal balance of conjunctival matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and tissue inhibitors (TIMPs). These enzymes serve to degrade extracellular matrix, possibly contributing to the pathogenesis of CCh.12 Specifically, Li, et al. showed overexpression of MMP-1 and MMP-3 mRNA in tissue cultured conjunctivochalasis fibroblasts, versus normal human conjunctival fibroblasts. No difference was noted in MMP-2, TIMP-1, TIMP-2, and urokinase plasminogen activator in the same study. Further studies then showed that inflammatory mediators tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and interleukin-1β (IL-1β) may increase expression of MMP-1 and MMP-3 in conjunctivochalasis fibroblasts.13 Other proinflammatory cytokines, tear IL-6 and IL-8, were shown to be increased in the tear film of CCh patients.14 It has been suggested that this interaction of MMPs and their inhibitors, which normally participate in connective tissue degradation and remodeling, may offer some insight into the clinical manifestation of loose, redundant conjunctiva.

Grading Systems

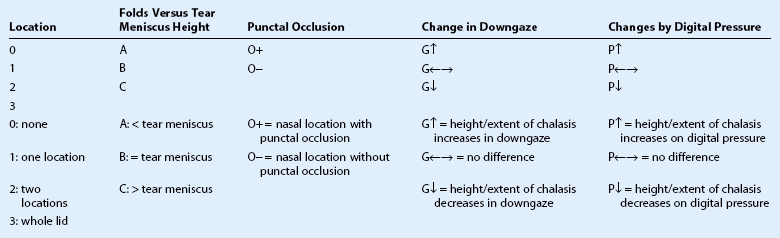

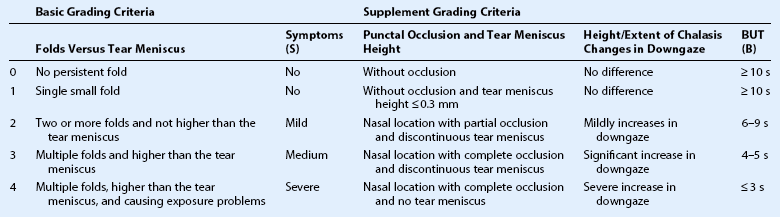

Several grading systems have been developed to describe conjunctivochalasis. The first group to categorize CCh was Höh et al., who looked at the number of lid-parallel conjunctival folds (LIPCOF).15 They noted the number of LIPCOF had a high predictive value for diagnosis of keratoconjunctivitis sicca (Table 20.1). At present, the most widely used grading system was proposed by Meller and Tseng in 1998 (Table 20.2) who adapted the scale by Höh and associates and included the extent of CCh, changes with downgaze and digital pressure, and presence of punctual occlusion.2 This system has been utilized in the majority of studies to define extent of CCh. The newest grading system proposed by Zhang et al. in 2011 (Table 20.3) further modified Meller and Tseng’s approach by including three symptoms (epiphora, feeling of dryness, and foreign body sensation) and unstable tear film-break up time (BUT).8 The authors felt these modifications were necessary to flesh out those ‘asymptomatic, normal older people’ they felt added to the very high prevalence rates of CCh noted in some epidemiologic studies. The validity of this scale needs to be proven in future studies.

Table 20.1

Classification of Conjunctivochalasis Using the Lid-Parallel Folds (LIPCOF) Method Grading of Conjunctivochalasis*

| Grade | Number of Folds and Relationship to the Tear Meniscus Height |

| 0 | No persistent fold |

| 1 | Single, small fold |

| 2 | More than two folds and not higher than the tear meniscus |

| 3 | Multiple folds and higher than the tear meniscus |

*Modified from Höh et al.15 with permission of the authors and Ophthalmologe.

(Reprinted with permission from: Meller D, Tseng SCG. Conjunctivochalasis: literature review and possible pathophysiology. Surv Ophthalmol 1998;43:225–32. Copyright Elsevier, 1998.)

Table 20.2

Proposed New Grading System for Conjunctivochalasis*

*The new grading system defines the extension of redundant conjunctiva as grade 1 = 1 location, 2 = 2 locations, 3 = whole lid. For 1 and 2, it is further specified as T, M, N if conjunctivochalasis is found in the temporal, the middle (or inferior to the limbus), and the nasal aspect of the lower lid, respectively. For each location (T, M, and N), further notation is given to indicate if the height of folds is less that (A), equal to (B), or greater than (C) the tear meniscus height. If it is found in the nasal (N) location, the extent of chalasis is further determine as to whether it occludes the inferior puncta. For each location, it is further graded as G⇑ if its height is greater than, as G⇔ if equal to, and as G⇓ if less than the tear meniscus height. Likewise it is further graded as P⇑, P⇔, and P⇓ if it is worse, no difference, or better with digital pressure (P), respectively.

(Reprinted with permission from: Meller D, Tseng SCG. Conjunctivochalasis: literature review and possible pathophysiology. Surv Ophthalmol. 1998;43:225–32. Copyright Elsevier, 1998.)

Table 20.3

Modified Meller and Tseng’s Grading System for Conjunctivochalasis Used in the Present Study*

Grade II, Grade III, and Grade IV are also defined as ‘clinically significant conjunctivochalasis’.

*Symptoms indicate dryness, foreign body sensation, and epiphora, evaluated by the patients themselves; BUT: break-up time (seconds).

(Reprinted with permission from: Zhang X, Li Q, Zou H, et al. BMC Public Heath. 2011;11:198.)

Therapeutic Options

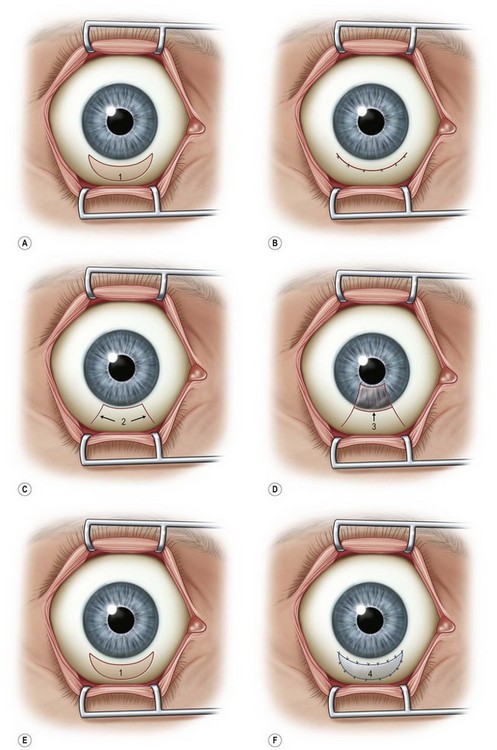

Surgical options include a variety of methods to reduce the amount of redundant conjunctival folding. The most commonly employed procedure involves simple conjunctival excision of the redundant tissue. Conjunctival resection was initially described using a crescentic excision of conjunctiva 5 mm posterior to the limbus and closed with absorbable suture.1

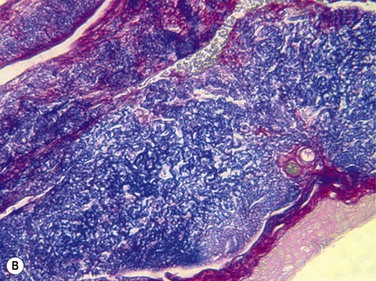

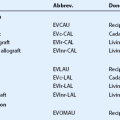

Several other techniques have shown to decrease or resolve symptoms of CCh; however, there have not been prospective comparative analysis to determine the relative efficacy of these different surgical procedures. These other procedures include conjunctival fixation to sclera with three 6-0 Vicryl sutures16 and elliptical excision of redundant conjunctiva.3 Serrano and Mora modified the excision technique by creating a peritomy, just posterior to the limbus with two radial, relaxing incisions to avoid scarring or retraction of the inferior fornix.17 Amniotic membrane transplantation for CCh has been described as a treatment with either suture fixation of the amniograft18–20 or fixation through the use of fibrin glue.21 However, CCh is a condition of redundant conjunctiva, so most clinicians feel that the addition of other tissue, such as amniotic membrane is not warranted. Fibrin glue has also been used as an adjunctive step to conjunctival resection and has been shown to be effective (Fig. 20.4).22

The more minimally invasive superficial thermocautery of the inferior conjunctiva, has also shown to improve symptoms of CCh and improve conjunctival laxity.23,24 Nakasato and colleagues described a novel technique where ligation testing was used to predict appropriate candidates to undergo thermocautery of the inferior bulbar conjunctiva. This allowed them to treat symptomatic patients with CCh in an outpatient setting and to stratify patients into groups that were more likely to respond to therapy. The ligation test technique describes an 8-0 silk suture formed into a loop, with forceps used to grasp redundant conjunctiva through the loop 3–4 mm inferior to the limbus until the CCh disappears. The loop is then tightened to ligate the excess tissue. Once anesthesia has worn off, patients were evaluated for improvement or resolution of CCh symptoms, and if some improvement is noted, they were selected for thermocautery treatment. Following thermocautery, disappearance of symptoms was noted in 92.3% of treated eyes, and symptoms improved in the remaining 7.7% of eyes.23 Because the severity of CCh increases with digital pressure and downward gaze, lid tightening procedures tend to worsen the symptoms of CCh-related dry eye.7 Extensive conjunctival resections should also be avoided in order to minimize complications, such as contraction of the fornices, cicitricial entropion, and restriction of extraocular movement. When sutures are employed in the technique, increased foreign body sensation, suture-induced granulomas, and prolonged inflammatory reactions can be seen. Other early complications include chemosis, hyperemia, subconjunctival hemorrhage, and infection. Late complications, such as scar formation and residual or recurrent CCh are possible.

References

1. Hughes, WL. Conjunctivochalasis. Am J Ophthalmol. 1942;25:48–51.

2. Meller, D, Tseng, SCG. Conjunctivochalasis: literature review and possible pathophysiology. Surv Ophthalmol. 1998;43:225–232.

3. Liu, D. Conjunctivochalasis. A cause of tearing and its management. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 1986;2:25–28.

4. Di Pascuale, MA, Espana, EM, Kawakita, T, et al. Clinical characteristics of conjunctivochalasis with or without aqueous tear deficiency. Br J Ophthalmol. 2004;88:388–392.

5. Yokoi, N, Komuro, A, Nishii, M, et al. Clinical impact of conjunctivochalasis on the ocular surface. Cornea [Clinical Trial]. 2005;24(Suppl. 8):S24–S31.

6. Mimura, T, Usui, T, Yamamoto, H, et al. Conjunctivochalasis and contact lenses. Am J Ophthalmol. 2009;148:20–25. [e1].

7. Mimura, T, Yamagami, S, Usui, T, et al. Changes of conjunctivochalasis with age in a hospital-based study. Am J Ophthalmol. 2009;147:171–177. [e1].

8. Zhang, X, Li, Q, Zou, H, et al. Assessing the severity of conjunctivochalasis in a senile population: a community-based epidemiology study in Shanghai, China. BMC Pub Health. 2011;11:198.

9. de Almeida, SF, de Sousa, LB, Vieira, LA, et al. Clinic-cytologic study of conjunctivochalasis and its relation to thyroid autoimmune diseases: prospective cohort study. Cornea. 2006;25:789–793.

10. Francis, IC, Chan, DG, Kim, P, et al. Case-controlled clinical and histopathological study of conjunctivochalasis. Br J Ophthalmol. 2005;89:302–305.

11. Watanabe, A, Yokoi, N, Kinoshita, S, et al. Clinicopathologic study of conjunctivochalasis. Cornea. 2004;23:294–298.

12. Li, DQ, Meller, D, Liu, Y, et al. Overexpression of MMP-1 and MMP-3 by cultured conjunctivochalasis fibroblasts. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2000;41:404–410.

13. Meller, D, Li, DQ, Tseng, SCG. Regulation of collagenase, stromelysin, and gelatinase B in human conjunctival and conjunctivochalasis fibroblasts by interleukin-1beta and tumor necrosis factor-alpha. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2000;41:2922–2929.

14. Erdogan-Poyraz, C, Mocan, MC, Bozkurt, B, et al. Elevated tear interleukin-6 and interleukin-8 levels in patients with conjunctivochalasis. Cornea. 2009;28:189–193.

15. Höh, H, Schirra, F, Kienecker, C, et al. Lid-parallel conjunctival folds are a sure diagnostic sign of dry eye. Ophthalmologe. 1995;92:802–808.

16. Otaka, I, Kyu, N. A new surgical technique for management of conjunctivochalasis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2000;129:385–387.

17. Serrano, F, Mora, LM. Conjunctivochalasis: a surgical technique. Ophthalmic Surg. 1989;20:883–884.

18. Meller, D, Maskin, SL, Pires, RT, et al. Amniotic membrane transplantation for symptomatic conjunctivochalasis refractory to medical treatments. Cornea. 2000;19:796–803.

19. Georgiadis, NS, Terzidou, CD. Epiphora caused by conjunctivochalasis: treatment with transplantation of preserved human amniotic membrane. Cornea. 2001;20:619–621.

20. Maskin, SL. Effect of ocular surface reconstruction by using amniotic membrane transplant for symptomatic conjunctivochalasis on fluorescein clearance test results. Cornea. 2008;27:644–649.

21. Kheirkhah, A, Casas, V, Blanco, G, et al. Amniotic membrane transplantation with fibrin glue for conjunctivochalasis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2007;144:311–313.

22. Brodbaker, E, Bahar, I, Slomovic, AR. Novel use of fibrin glue in the treatment of conjunctivochalasis. Cornea. 2008;27:950–952.

23. Nakasato, S, Uemoto, R, Mizuki, N. Thermocautery for Inferior conjunctivochalasis. Cornea. 2012;31:514–519.

24. Kashima, T, Akiyama, H, Miura, F, et al. Improved subjective symptoms of conjunctivochalasis using bipolar diathermy method for conjunctival shrinkage. Clin Ophthalmol. 2011;5:1391–1396.