Conjunctival Limbal Autograft

Introduction

In a discussion at the Cornea World Congress in 1964, José Barraquer described the use of an autograft of limbus from the unaffected eye in cases of superficial burns as a preparatory procedure before keratoplasty.1 He noted that this improved the state of the corneal epithelium but the mechanism was not discussed. In 1966, Strampelli et al. reported two cases of improvement in vascularized opaque corneas with transplantation of a complete ring of limbus from the other eye.2 They described the technique in more detail at the Second International Corneo-Plastic Conference in London in 1967.3 It was not until some time later that the role of the limbus as the niche for the stem cells responsible for the corneal epithelium was elucidated, and Kenyon and Tseng reported on the use of autografts of conjunctiva and limbus for management of diffuse unilateral limbal deficiency in 1989.4 Conjunctival limbal autografts (CLAU) were described within a classification system for epithelial transplantation proposed by Holland and Schwartz in 1996.5 Since then, there have been many reports describing the use of limbal autografts, and the role of CLAU in management of unilateral ocular surface disease has been comprehensively reviewed.6–9

Indications

Clinical signs of limbal deficiency include varying combinations of conjunctivalization of the cornea, with associated vascularization and fibrovascular pannus, persistent or recurrent epithelial defects and scarring or stromal haze.9 Symptoms include poor vision, chronic or recurrent discomfort and photophobia.

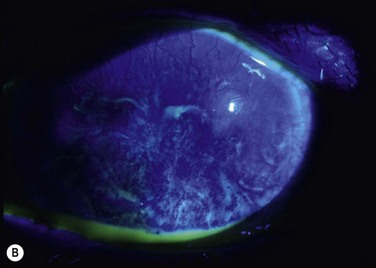

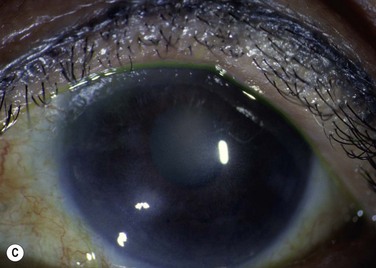

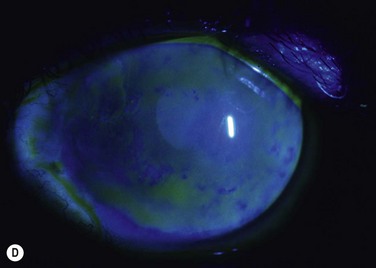

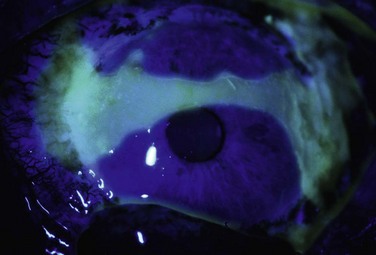

Probably the most common use of limbal autografts has been in surgery for pterygium in the form of an ipsilateral limbal translocation, though there is little evidence that the limbal part of the autograft adds any benefit over a standard conjunctival autograft.10 In most other forms of unilateral limbal deficiency the autograft is harvested from the other eye. In this situation, a unilateral chemical injury is probably the most common clinical scenario. Figure 40.1 demonstrates improvement in the ocular surface with CLAU after chemical injury.

Preoperative Assessment and Considerations

It has been recognized that the state of the rest of the ocular surface is critical to the outcome of limbal transplantation. Preoperative assessment must include thorough examination of the ocular adnexa and ocular surface. The nature of chemical injuries and many of the other causes of limbal deficiency is such that other ocular surface or adnexal problems are commonly associated. Two important considerations in determining management are whether the condition is unilateral or bilateral and whether there is conjunctival involvement.5

Lid malposition, symblepharon, and trichiasis all need to be dealt with prior to limbal transplantation. The most common pre-existing problem is that of dry eye and this is a major prognostic factor.11 If aqueous tear function is inadequate, then punctal occlusion should be performed. Blepharitis or ocular surface inflammation should be controlled optimally before surgery if possible.

Surgical Technique

Recipient Preparation

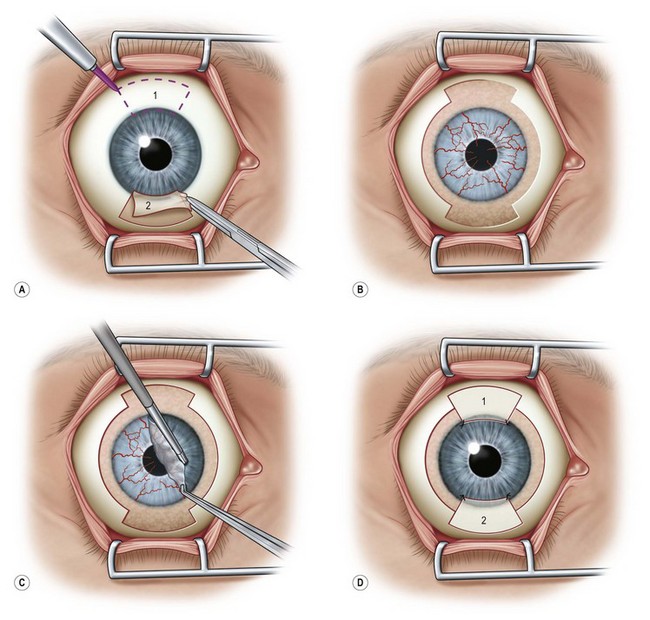

It is best to prepare the recipient eye first so that bleeding can be controlled. For complete limbal deficiency, a 360° limbal peritomy is performed with Westcott scissors (Fig. 40.2A). The conjunctiva is undermined to allow it to be recessed several millimeters in the superior and inferior locations. The pannus on the cornea will be easily removed except where the stroma has been damaged. In those areas it will be more adherent but can be removed with blunt dissection or scraping with a hockey-stick blade (Fig. 40.2B). With full conjunctivalization of the cornea, the usual adherence of the limbal tissue is lost and usually it is easily removed around the limbus. Cautery is applied lightly, if required, to minimize further trauma. Bleeding will generally stop with the wait during preparation of the donor. A bed can be prepared for the donor as described below. The ocular surface is moistened and the speculum removed, and the eye closed or covered while the donor is prepared.

Donor Preparation

Several techniques have been described for donor preparation and fixation.6 The general approach is to remove 2 to 3 clock-hours (60–90°) of limbus from the superior and inferior locations of the donor eye (Fig. 40.2C).

Placement of the Donor Tissue

The recipient limbus can be prepared in the same fashion as the donor to provide a discrete corneal edge for the donor tissue to butt against. Care is needed not to make the recipient bed too deep or there will be a step up at the corneal edge that will inhibit epithelial healing. Otherwise, the donor tissue may be just placed on the recipient limbus (Fig. 40.2D). Fibrin glue is applied to the recipient and the donor tissue placed in anatomical position and smoothed out. Alternatively, the graft is sutured in place at each end to the sclera either with 10-0 polyglactin (Vicryl) or 10-0 nylon. Braided polyglactin, though easier to handle, causes more tissue reaction and inflammation and loosens very quickly. The corners of the conjunctival part of the graft are then tacked to episclera and the recipient conjunctival edge with enough tension to keep it evenly spread out. Even with glue, it is prudent to place sutures at each end of the graft to prevent any chance of it dislodging. The donor conjunctival edge can be approximated carefully to the recessed recipient conjunctiva with sutures of just two single throws of 10-0 polyglactin as it should not be under tension. It is important for the assistant to keep the surface wet with balanced salt solution during this part of the procedure. A viscoelastic can be used to protect the surface but it tends to make suturing somewhat more difficult as the fine suture material sticks to it.

Postoperative Management

There is generally some immediate swelling of the transplanted conjunctiva. The graft typically revascularizes within 5 days; there is then gradual thinning of the conjunctiva over weeks. Corneal epithelium extends from the central edges of the graft in a convex pattern and progresses centrally over days (Fig. 40.3). The rate of healing depends on the state of the ocular surface at the time of transplantation and presumably other general factors, such as the age of the patient. The advancing edges of the corneal epithelium meet in the central cornea and may produce a typical healing line. The last part to heal is usually in the 3 and 9 o’clock zones of the peripheral cornea when superior and inferior grafts are used. If the conjunctival epithelium reaches the limbus before the corneal epithelium has healed, it may need to be removed by sequential sector conjunctival epitheliectomy (SSCE) as suggested for management of partial limbal deficiency9 to prevent recurrent conjunctivalization of the cornea.

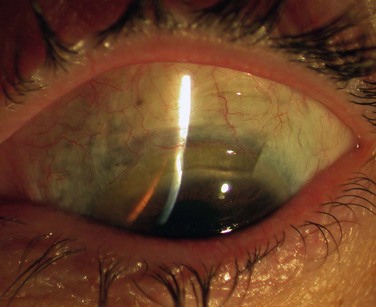

The donor site heals with slight thinning and some superficial vascularization of the cornea (Fig. 40.4).

Problems

Complications may occur with CLAU surgery and have been reviewed recently.12 These may relate to case selection and preoperative management, as well as to surgical technique. Damage to the donor eye is a major concern. There is one report of limbal deficiency developing in a donor eye in a case of contact lens-induced epitheliopathy that was not strictly unilateral.13

There has been one report of medium-term attenuation in viability of CLAU with progressive conjunctival ingrowth within a year of transplantation in three consecutive cases.14 This has not been reported elsewhere.

Variations and Combination with other Procedures

It is not clear what minimum amount of limbus is required to provide a stable and clear surface in cases of total limbal deficiency. Given that in many clinical situations only a few clock hours of normal limbus are required to keep a cornea clear, it should not always be necessary to transplant 180° of limbus from the donor. However, the situation in the affected eye is not normal. Liang et al. have reported a satisfactory outcome from transplanting 60° of limbus combined with amniotic membrane transplantation.8

It has been suggested that amniotic membrane may facilitate expansion of remaining limbal stem cells in chemical injuries and it may do so in the autograft situation. Amniotic membrane transplantation has been used extensively in combination with CLAU and may reduce inflammation on the ocular surface, as well as providing a better environment for the corneal epithelium to recover.8

CLAU has been combined with penetrating or lamellar keratoplasty, either at the same time or subsequent to healing of the corneal surface, but there is little information about the longer-term success of keratoplasty in combined cases versus delayed keratoplasty.7

In cases of severe unilateral conjunctival and limbal disease with significant symblepharon formation, CLAU has been combined with keratolimbal allograft tissue (KLAL) at the 3 and 9 o’clock meridian (modified Cincinnati procedure) to prevent failure from conjunctival invading from the 3 and 9 o’clock meridians.15 These patient require systemic immunosuppression to prevent rejection of the KLAL tissue. However, the duration of immunosuppression is shorter than in those patients with complete allografts.

References

1. Barraquer, J. Panel Three Discussion. In: King JH, McTigue JW, eds. The Cornea World Congress. Washington: Butterworths; 1965:354.

2. Strampelli, B, Restivo Manfridi, ML. Total keratectomy in leukomatous eye associated with autograft of a keratoconjunctival ring removed from the controlateral normal eye. Ann Ottalmol Clin Ocul. 1966;92:778–786.

3. Strampelli, B. Ring autokeratoplasty. In: Rycroft PV, ed. Corneo-plastic surgery. Oxford: Pergamon Press; 1969:253–275.

4. Kenyon, KR, Tseng, SCG. Limbal autograft transplantation for ocular surface disorders. Ophthalmology. 1989;96:709–723.

5. Holland, EJ, Schwartz, GS. The evolution of epithelial transplantation for severe ocular surface disease and a proposed classification system. Cornea. 1996;15:549–556.

6. Basti, S, Rao, SK. Current status of limbal conjunctival autograft. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2000;11:224–232.

7. Cauchi, PA, Ang, GS. Azuara-Blanco A, et al. A systematic literature review of surgical interventions for limbal stem cell deficiency in humans. Am J Ophthalmol. 2008;146:251–259.

8. Liang, L, Sheha, H, Li, J, et al. Limbal stem cell transplantation: new progresses and challenges. Eye. 2009;23:1946–1953.

9. Dua, HS, Miri, A, Said, DG. Contemporary limbal stem cell transplantation – a review. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2010;38:104–117.

10. Kheirkhah, A, Hashemi, H, Adelpour, M, et al. Randomized trial of pterygium surgery with mitomycin C application using conjunctival autograft versus conjunctival-limbal autograft. Ophthalmology. 2012;119:227–232.

11. Santos, MS, Gomes, JA, Hofling-Lima, AL, et al. Survival analysis of conjunctival limbal grafts and amniotic membrane transplantation in eyes with total limbal stem cell deficiency. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005;140:223–230.

12. Baradaran-Rafii, AA, Eslani, MM, Jamali, JH, et al. Postoperative complications of conjunctival limbal autograft surgery. Cornea. 2012;31:893–899.

13. Jenkins, C, Tuft, S, Liu, C, et al. Limbal transplantation in the management of chronic contact-lens-associated epitheliopathy. Eye. 1993;7:629–633.

14. Basti, S, Mathur, U. Unusual intermediate-term outcome in three cases of limbal autograft transplantation. Ophthalmology. 1999;106:958–963.

15. Chan, CC, Biber, JM, Holland, EJ. The modified Cincinnati procedure: combined conjunctival-limbal autografts and keratolimbal allografts for unilateral severe ocular surface failure. Cornea. 2012;31:1264–1272.