Chapter 8 Congestive respiratory disorders

OVERVIEW AND AETIOLOGY

Congestive respiratory disorders are conditions that present with mucus build-up in the upper and/or lower respiratory tract. Rhinitis and sinusitis are the most common upper respiratory expression of congestion. Sinusitis is an inflammatory condition of one or more of the four paired paranasal sinuses.1 The condition may be classified by symptom duration (acute if < 4 weeks, chronic if > 12 weeks) or by aetiology (viral, bacterial, fungal or non-infectious).1,2 Chronic sinusitis is one of the most common long-term illnesses in the United States of America, where it affects approximately 14% of the population.3,4

Sinusitis presents with clinical features including:1,2

Sinusitis is usually bacterial in origin. Common organisms include Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, Streptococcus pyogenes, other streptococci and Neisseria spp.1,5

Lower respiratory congestion is usually associated with an acute infection, or chronic obstructive process, either reversible (such as asthma) or non-reversible (such as chronic obstructive airways disease (COAD).6

RISK FACTORS

Key factors in the development of sinusitis are sinus obstruction and/or impaired ciliary clearance of secretions. Inflammatory polyps were found to be a cause of chronic frontal sinusitis (requiring frontal sinus surgery) in 53% of sinus surgery cases.5,7 Other local conditions that predispose children to rhinosinusitis include an URTI, swimming and diving, enlarged and infected adenoids, vasomotor disturbance leading to obstruction of drainage and deflection of the nasal septum.8

Chronic sinusitis is often a concomitant presentation with other forms of respiratory atopy, such as allergic rhinitis,9 and suppressive treatment of hay fever is hypothesised to lead to the development of chronic sinus inflammation.

Dietary factors are often suggested to contribute to excess mucus production. Dairy, wheat and corn have been proposed to promote a more globular mucus, disable sinus drainage and promote antigen exposure.10 While certain individuals may be predisposed to inflammatory responses with certain foods, the concept that some foods are universally mucus-promoting is an oversimplification of the process.11 In people who believe this, however, the consumption of such products does dispose them to greater subjective respiratory symptoms,11 demonstrating a potential psychosomatic component. (For risk factors for lower respiratory tract (LRT) congestion, see Chapter 6 on respiratory infections and immune insufficiency and Chapter 7 on asthma.)

CONVENTIONAL TREATMENT

The predominant conventional treatment of sinusitis centres on antibiotics to control infection and corticosteroids to reduce acute inflammation.10,12 Adjunctive treatments include topical and oral decongestants and antihistamines to reduce mucosal blood flow, decrease tissue oedema and perhaps enhance drainage of secretions from the sinus ostia.10,12 In chronic or unresponsive cases, nasal endoscopic surgery may assist in clearance of the sinuses, and restoration of mucociliary activity.13

While antibiotics are frequently prescribed, a Cochrane review of 49 studies concluded that they produced insignificant cure rates, with only a small treatment effect on patients in a primary care setting.14 (For conventional treatment of LRT congestion, see Chapter 6 on respiratory infections and immune insufficiency and Chapter 7 on asthma.)

KEY TREATMENT PROTOCOLS

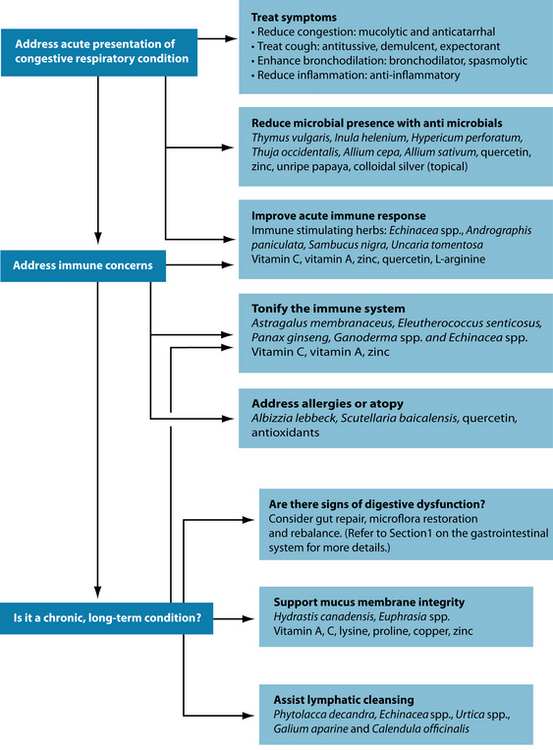

Acute immune support and reduction of pathogens will also be necessary in the acute infection. If congestion is chronic or repeated, then longer-term immune tonics and adaptogens should be used in order to strengthen the resistance of the individual. In forms of congestion linked to atopy, antiallergic substances and those which modulate hypersensitivity can be useful.

Reduce congestion in the sinuses and airways

Blocked sinuses: steam inhalations, heat therapy and nasal irrigation

With chronic sinusitis it is important to liquefy the congested secretions in an effort to clear the sinus passages. Herbal mucolytics act to thin out mucosal secretions and make them easier to expel.15 Trigonella foenum-graecum16 is particularly useful, especially as a hot infusion, with the heat and steam being an integral part of the process. It is important to warn your patient that they should expect a nasal discharge to result, so they can plan the best time for the intervention. If they know, they are also less likely to take antihistamines, which would suppress the desired effect. Other mucolytic herbs to consider are Foeniculum vulgare, Allium cepa, Armoracia rusticana and Allium sativum.17,18

An additional category of herbs applied in the case of sinus congestion are upper respiratory tract anticatarrhals, such as Euphrasia spp., Plantago lanceolata, Sambucus nigra and Hydrastis canadensis.18 Anticatarrhals differ from mucolytics in that their action involves the reduction of mucus production, rather than simply breaking it down to expel.19 Few well-designed clinical trials were found to substantiate the effectiveness of these interventions, but they have a history of traditional use.18,20 H. canadensis is traditionally contraindicated in acute inflammatory conditions of the mucous membranes but may be used in subacute or chronic conditions.18 A combination of Gentiana lutea, Primula veris, Rumex spp., Sambucus nigra and Verbena officinalis is approved by Commission E to treat sinusitis and seems to exert mucolytic or anticatarrhal, antiviral and anti-inflammatory effects in a number of trials.21,22

Nutritional mucolytics may also be very useful when included in a supplement regimen. N-acetylcysteine (NAC) is perhaps the most researched and broadly used mucolytic.23,24 The sulfhydryl group works to cleave disulphide bonds in mucous glycoproteins, making nasal secretions easier to expel.25 NAC has demonstrated the ability to increase the mucociliary clearance rate by 35%, in comparison to no effect by placebo.26

Proteolytic enzymes, including bromelain, may also be useful. Proteolytic enzymes show an ability to break down the naked peptide region of mucous glycoproteins when applied topically.25 There have been questions surrounding the bioavailability of these agents upon oral ingestion, but studies show that ingestion of the compounds leads to appreciable increases in their serum concentration.28,29,30 In a number of trials

POSSIBLE FENUGREEK ALLERGY

One study has found that fenugreek seed powder may contain a number of potential allergenic proteins. In most cases, this reactivity seems to be due to cross-reactivity with peanut sensitisation.19,2 While true fenugreek allergy is unlikely to be a concern, practitioners should be aware of the potential for cross-reactivity when using this mucolytic agent in patients with peanut allergies.

conducted on patients with chronic sinusitis or allergic rhinitis, the administration of bromelain (in addition to individualised conventional treatment) produced significant improvements in parameters including nasal mucosal inflammation, overall symptoms, breathing difficulties and nasal discomfort.30–32

One of the longer-standing traditional remedies for blocked sinuses and nasal congestion has been the inhalation of steam. Often this is with an additive (see below). Studies are mixed on the use of hot, moist air alone, with some positive trials33,34 and others showing no effect greater than room-temperature air.35,36

The ‘old wives’ tale’ cure of chicken soup may not be such a myth. The inhalation of hot air (from hot water) is known to help clear nasal congestion,35,36 but research has shown that hot chicken soup is more effective than hot water.37 The addition of aromatic spices and culinary herbs will also help to open up the nasal passages and clear secretions.38 As an additional benefit, the liquid component inhibits neutrophil migration, possibly helping reduce symptoms in infection.38

The use of botanicals may improve therapeutic effectiveness of steam inhalation. For example Commission E supports the use of inhalation of Matricaria recutita for inflammation and irritation of the respiratory tract.21 The essential oils of Cinnamomum zeylanicum, Thymus vulgaris, Mentha piperita, Perilla frutescens, Cymbopogon spp. and Eucalyptus spp. have demonstrated antibacterial activity against common respiratory pathogens through vapour contact, and thus may also be of use.39–41 One of the most common inhalants is eucalyptus oil; when administered via inhalation or as a chest rub, it has demonstrated ability to reduce nasal congestion and improve breathing function in those with respiratory infection.40,42 A German product combining cineol, limonene and alpha-pinene also has great efficacy in treating purulent mucosinusitis.43 These are constituents of many essential oils including Mentha piperita, citrus oils, Anethum graveolens, Pinus spp., Piper nigrum, Eucalyptus spp. and Melaleuca cajuputi.44 Other common inhalations include Mentha piperita, Lavandula spp., Pinus sylvestris, Melaleuca alternifolia and Rosmarinus officinalis.45 As an extension of this principle, local application of heat more generally has also been shown to alleviate the symptoms of allergic rhinitis.46,47

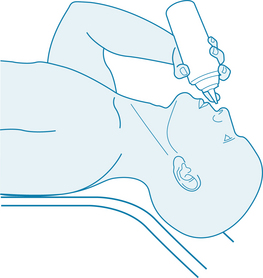

Nasal irrigation is another natural method of clearing sinus congestion. The origins of this technique lie in yogic and homoeopathic traditions.48,49 Jala neti is a Hatha yoga technique of pouring water in through one nostril using a neti pot so that it pours out the other. The method is believed to be an essential part of health maintenance, and is recommended three or four times a week.50,51 There are a number of positive trials of nasal irrigation among people with allergic rhinitis or chronic sinusitis.52 A Cochrane review in 2007 reported that nasal irrigation could improve the symptoms of chronic rhinosinusitis in the majority of patients, with few adverse effects.49 Benefits are derived not solely from the initial mechanical clearance of the airways, but also due to the physiological benefits of topical saline (sodium chloride), which has been proposed to improve mucus clearance, enhance ciliary beat activity, remove antigens, biofilm or inflammatory mediators, and to be protective of the mucous membranes.49 Sodium bicarbonate is also mucolytic in nature and may therefore be useful in nasal irrigation.53

One method of nasal irrigation is suggested in Figure 8.1, but there are many slight variations, and it is recommended that the practitioner become comfortable with their chosen technique themselves first before recommending it to others. It should also be noted that bulb syringe irrigators have been found to be a potential source of contamination in rhinosinusitis,54 so attempts should be made to ensure the cleanliness of the equipment and procedure.

Phlegm and cough

With regards to mucus congestion and cough, a number of different treatment strategies may be used. Dry (non-productive) or particularly severe coughs can benefit from suppression with an antitussive agent. Otherwise, although it may be annoying, it is best not to suppress the productive cough reflex, as it helps to clear infectious organisms from the airways.55

Mucolytics and anticatarrhals may also be of use where there is a great deal of phlegm, mucus and/or congestion present. These agents will help to reduce catarrhal congestion of the upper or lower respiratory system. As with mucolytic pharmaceuticals, their mechanism of action is not fully understood, but they may act by altering the mucopolysaccharide structure of mucus, decreasing its elasticity or viscosity.24

Herbal medicines with demulcent action may help to reduce a cough if it is a reflex response to hyperactive or irritated receptors in the oropharynx.55 Treatments used in Western herbal traditions for productive cough include Thymus vulgaris, Glycyrrhiza glabra, Lobelia inflata and Polygala senega.21 Additionally, Verbascum thapsus, Tussilago farfara and Althaea officinalis are marked demulcents and antitussives indicated for dry or unproductive coughs.21 Some herbs, such as Prunus serotina, are primary antitussives; however, caution needs to be applied when prescribing these as they can suppress a cough despite there being mucus to expectorate. This may potentially exacerbate an acute respiratory infection.

Glycyrrhiza glabra is approved by Commission E to treat upper respiratory catarrh and cough.21 In addition to its expectorant and antitussive actions, G. glabra has anti-inflammatory, immune-enhancing and mucoprotective effects, the traditional reason behind its use in respiratory tract infections. The herb has demonstrated antitussive effects in animal studies, most likely due to the component liquiritin and its metabolite, liquiritigenin.58 Thymus vulgaris has been used successfully in a large trial for the treatment of bronchial cough.59 It demonstrates an ability to improve mucociliary clearance in vivo, although the mechanism remains to be elucidated.60 In conjunction with the herbs Sambucus nigra, Primula veris, Rumex acetosa, Verbena officinalis and T.vulgaris Gentiana lutea, the extract demonstrated ability to reduce the frequency of symptomatic coughing fits.61,62 It is also traditionally recommended for use in respiratory tract infections as an extract or gargle due to its antimicrobial and antitussive qualities.21,57,63

In the case of productive cough, Inula helenium is another key herb to use, due to its combined effects as a stimulating expectorant and antibacterial agent.64 Given that it contains a high level of mucilage, it also contributes to soothing the mucous membranes, thus covering a wide range of the required therapeutic actions. It is also a respiratory spasmolytic that is well tolerated in long-term therapy.59 Traditional eclectic texts purport Althaea officinalis to be useful in the case of catarrh or irritated mucous membranes.17,65 The polysaccharide constituent has demonstrated inhibition of coughs caused by laryngopharangeal and tracheobronchial irritation.66 New research indicates a relatively pronounced antibacterial effect (stronger than that of Thymus vulgaris) on various strains of E. coli, exerted via inhibition of microbial metabolism.67 Althaea officinalis is more indicated for an irritating than a congestive cough.21

Adhatoda vasica is mentioned in the Vedas for treatment of a number of respiratory illnesses, and is also listed in the Pharmacopoeia of India.68 Extracts of the aerial parts administered orally exhibit the ability to inhibit both mechanical and chemically induced coughs.68 When this treatment was combined with Echinacea spp. and Eleutherococcus senticosus extracts in clinical trials, it produced additive benefits in treating URTI.69 Patients showed greater improvement in many of the parameters tested, including severity of coughing, frequency of coughing, efficacy of mucus discharge in the respiratory tract, nasal congestion and general feeling of sickness.69

Inhaled preparations containing menthol, such as eucalyptus oil, have shown the ability to significantly increase tracheobronchial clearance of mucus from the lungs70 and help to reduce cough.71

As discussed above, nutritional mucolytic agents such as N-acetylcysteine and proteolytic enzymes may be useful in LRT congestion. Dietary treatment should also be employed. Allium spp. is an antimicrobial, expectorant, mucolytic and anti-inflammatory agent.57 The respiratory system is one of the main systems to benefit from the antimicrobial action of its volatile oil, as it is excreted from the lungs. Culinary herbs such as Pimpinella

CHRONIC OBSTRUCTIVE AIRWAYS DISEASE

Overview

Chronic obstructive airways disease (COAD) or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) includes emphysema and chronic bronchitis. Unlike asthma, the airflow obstruction is only partially reversible, and the disease process is progressive and irreversible.72 Airflow obstruction is usually associated with abnormal inflammation of the airways, parenchyma and pulmonary vasculature in response to chronic inhalation of noxious particles or gases.5,72,73

COAD is diagnosed when a patient has spirometry readings of:

CAM interventions

Mucolytics and anticatarrhals: Trigonella foenum-graecum, Plantago lanceolata, Hydrastis canadensis, Foeniculum vulgare, Allium cepa, Armoracia rusticana, Allium sativum, N-acetylcysteine, 80,23,81 bromelain, trypsin, papain and aromatic inhalants.82

Anti-inflammatory: Boswellia serrata, Curcuma longa, Zingiber officinale, omega-3 fatty acids, quercetin, fish, antioxidant foods (fruit and vegetables) 83–8527 and possibly antioxidant nutrients,7,86,87 Camellia sinensis.85

Bronchodilating: Adhatoda vasica, Euphorbia spp., Coleus forskohlii, Grindelia camporum, Glycyrrhiza glabra, magnesium88 (dietary and supplemental).

Mucous membrane trophorestoratives: Hydrastis canadensis, vitamins A and C, zinc, selenium, adequate protein intake.89

anisum, Foeniculum vulgare, Trigonella foenum-graecum and Zingiber officinale are warming expectorants and can be incorporated into treatment, either in food or as hot beverages.57

Reduce microbial colonisation

Herbal antimicrobials (encompassing antivirals, antibacterials and antifungals) differ from some pharmaceutical products in that they usually exert a biocidal or bacteriostatic effect on the pathogen rather than being directly cytotoxic. Biocidal agents act via a number of mechanisms, at a number of different target sites in the cell. The combined overall activity seems to result in the bactericidal death of the microbe.90 According to Maillard, when used at lower doses, biocides exert a bacteriostatic effect, inhibiting the growth and colonisation of a pathogen.90 Although more research is needed in the area, it seems that herbal agents (given at the right doses) exert a bacteriostatic, rather than a cytotoxic or even biocidal, effect.

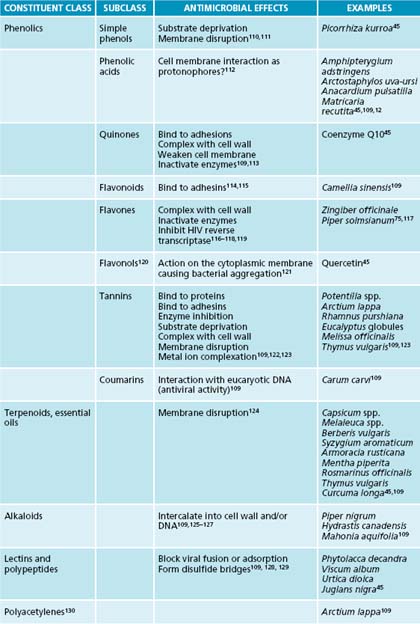

While there are many individual constituents which have been identified as antimicrobial, whole plant extracts remedies seem to be more efficacious at clearing pathogens due to synergism between components.91 For further information on plant compounds and their antimicrobial efficacy, see Table 8.1.

Antimicrobial herbs traditionally recommended for the respiratory system are Allium sativum, Inula helenium, Hydrastis canadensis and Thymus vulgaris. The essential oil of Thymus vulgaris exhibits some of the most pronounced antimicrobial effects of herbs that have been scientifically evaluated. It contains a multitude of compounds with activity against microorganisms, including thymol, carvacrol, luteolin and linalool.91,92 The combined effect of these is more potent than the individual constituents alone, illustrating the importance of using whole plant extracts for the most rapid antimicrobial effects.91 When tested against a number of the most common bacterial respiratory pathogens, T. vulgaris oil exhibited marked inhibitory effects on bacterial cell growth.93 The two other oils with marked significant action against these pathogens were Cinnamomum zeylanicum and Syzygium aromaticum.93 It is interesting to note that these effects were just as strong in antibiotic multi-resistant strains of bacteria, suggesting a role for increasing use of botanical agents in clearing respiratory infection.93 When combined with either primrose herb or ivy leaf extract, T. vulgaris shows marked efficacy in treating the symptoms and shortening the duration of acute bronchitis, an effect which is likely to be due in part to its antimicrobial action.62,63,94

Inula helenium also exhibits antimicrobial activity in vitro, but clinical trials of the herb are sorely lacking.65 Among its constituents, I. helenium contains thymol derivatives, and thus, at least in theory, some of the results of research with thyme oil may be extrapolated.95 Among the most potent antivirals in the herbal repertory are Hypericum perforatum and Thuja occidentalis. The hypericin component of H. perforatum is especially active against enveloped viruses, such as HIV and herpes simplex while T. occidentalis has a broader spectrum of viricidal targets.96 When T. occidentalis is given in combination with Baptisiae tinctoriae radix, E. purpureae radix and E. pallidae radix, the mixture exhibits ability to inhibit Influenza A virus pathology in animals.97 One widely available antimicrobial is Allium sativum.98 It has demonstrated activity against a number of bacteria, fungi and viruses implicated in respiratory infection, with some of its most potent constituents being allicin and allitridin.99–102 In a recent trial, intranasal garlic powder was shown to decrease the likelihood of contracting an airborne infection while travelling.103

Increasing food intake of shallots (Allium ascalonicum), garlic and onions (Allium cepa) will also provide the active organosulfur compounds and exert an antimicrobial effect, and be beneficial in treating respiratory infection.98,104,105 These foods will be at their most potent fresh or as close to fresh as possible.105 Other nutrients and foods that exhibit bacteriostatic qualities are zinc and unripe papaya.106,107

If considering a topical throat spray or gargle, suspended nanoparticles of zinc and silver colloidal may be useful, as they demonstrate antimicrobial (bacteriostatic and bactericidal) efficacy against a range of organisms including Enterococcus faecalis, Staphylococcus spp., Streptococcus pyogenes, Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Escherichia coli.107,108

Support immune response

Pelargonium sidoides has been found to be significantly superior to placebo in the treatment of acute rhinosinusitis131 with decreased debilitating symptoms and faster recovery. The activity of this herb is likely to be due to moderate antimicrobial activity and marked immune modulating activity, including an ability to alter the release of tumour-necrosis factor (TNF-α) and nitric oxide.132

Vitamin C has proven efficacious in the treatment of chronic sinusitis and allergic rhinitis. As a nutrient, it enhances both innate and adaptive components of the immune system, including natural killer cells, T-cells and B-cells.133 It is also antiallergic, in that it stabilises mast cells and inhibits histamine release.134 Levels of ascorbic acid, vitamin E, copper and zinc were found to be lower in children with chronic rhinosinusitis than in controls without the condition.135 Treatment of allergic rhinitis with an ascorbic acid solution intranasally three times daily has been shown to reduce symptoms in up to 74% of treated subjects. They experienced a decrease in nasal secretions, blockage and oedema.136

Allergic concerns may also be treated with Urtica dioica, which may inhibit inflammation, ironically, through its histamine content, which inhibits leukotriene formation.137 The herb has demonstrated success in treating allergic rhinitis, with all treated patients in a randomised controlled trial (RCT) reporting improved global assessments.138 Other antiallergic agents include quercetin and the herbs Albizzia lebbeck and Scutellaria baicalensis. (Refer to Chapter 6 on respiratory infections and immune insufficiency and Chapter 7 on asthma for review of the evidence.)

Support the integrity of the mucous membranes

Continual goblet cell activation and mucus production may compromise the mucosal linings of the airways. This necessitates support of the mucous membranes themselves through herbal mucous membrane trophorestoratives and nutritionally with collagen supportive nutrients. Hydrastis canadensis and Euphrasia spp. are traditionally indicated for the support of mucosal surfaces in the body, especially in the upper respiratory tract.18,64 At present, no pharmacological research or clinical trials have been found to substantiate these effects.

Nutrients that are important in the healing of wounds and help to support the integrity of collagen, epithelium and mucous membranes are vitamins A and C, lysine, proline and zinc. In addition to its antioxidant role, vitamin C is required for the conversion of proline and lysine to hydroxyproline and hydroxylysine so that they may be incorporated into collagen structures.113 Zinc is a cofactor for RNA and DNA polymerase, meaning that it is essential for DNA replication, repair and cell proliferation.139 It also stimulates reepithelialisation, fibroblast proliferation and is involved with collagen synthesis,139,140 and thus is essential for the correct structure of the airways. Copper is also essential for collagen and elastin cross-linking.139

Vitamin A is essential for the strength and health of the mucous membranes and epithelial integrity.141,142 It assists ‘normal endodermal differentiation as well as maintaining balanced cell proliferation, differentiation and apoptosis’.143 Studies have repeatedly demonstrated the beneficial effects of vitamin A supplementation on gastrointestinal mucosa,144 and the benefits may be extrapolated to also apply to the respiratory mucosa.

Support elimination via the lymphatic system

The idea of lymphatic cleansing is a traditional naturopathic approach to many chronic congestive conditions, including respiratory, musculoskeletal and skin disorders. The beneficial herbal actions are lymphatic and alterative, and herbs such as Phytolacca decandra, Echinacea spp., Urtica spp., Galium aparine and Calendula officinalis are viable options.20

INTEGRATIVE MEDICAL CONSIDERATIONS

Yoga

Participation in yoga programs may be of benefit in congestive disorders. After participating in a specially adapted program, elderly COAD sufferers were able to tolerate more activity without dyspnoea-related distress and improved functional performance.145 One session of yogic breathing techniques alone may produce favourable respiratory changes in sufferers.146

Acupuncture

A review147 examined seven high-quality RCTs and concluded that there was sufficient evidence to recommend acupuncture for improving symptoms of perennial rhinitis. Vasomotor rhinitis has also been shown to respond favourably to acupuncture–patients in a recent trial showed significant improvement in nasal sickness score both over baseline and in comparison to controls given sham acupuncture.148

In COAD, acupuncture may be useful due to its ability to reduce disease-related dyspnoea.149,150 Acu-TENS also produces increased FEV and decreased dyspnoea in patients compared to controls, even after a single 45-minute session.151

Reflexology and massage

An early trial into reflexology treatment of COAD shows some moderate improvements, perhaps relating to the increased relaxation felt by patients.152 In a small trial of five patients treated with twenty 4-weekly treatments of neuromuscular release massage therapy, four of these experienced increases in thoracic gas volume, peak flow and FVC.153

Aromatherapy

Aromatherapy is most useful in these conditions when used as an inhaled preparation. Most of the beneficial essential oils have been covered above.

Example treatment

Herbal and nutritional prescription

Herbal formula

| Echinacea root blend∗ 1:2 | 20 mL |

| Euphrasia officinalis 1:2 | 20 mL |

| Foeniculum vulgare 1:2 | 15 mL |

| Pelargonium sidoides 1:5 | 20 mL |

| Albizzia lebbeck 1:2 | 25 mL |

| 100 mL |

Albizzia lebbeck is an antiallergic herb to reduce the need for antihistamine medication.

Expected outcomes and follow-up protocols

The use of mucous membrane trophorestoratives (for example, Hydrastis canadensis) and tonics (for example, Astragalus membranaceus and Eleuthrococcus senticosus) may be of assistance in preventing a flare-up after the acute infection has abated.58 Signposts of recovery include reduction of the severity and the frequency of the sinusitis. Over time sinus pain and tenderness should decline and the infectious flare-ups should abate.

| INTERVENTION | KEY LITERATURE | SUMMARY OF RESULTS |

|---|---|---|

| N-acetylcysteine (NAC) | In vitro, decreases the viscosity and elasticity of mucopurulent nasal mucus and tracheobronchial secretions.154,53 | |

| NAC increases mucociliary clearance in people with slow mucociliary clearance. These people are in a higher risk category for congestive bronchopulmonary disease.26 | ||

| Thymus vulgaris | ||

| In animal studies, improves mucociliary clearance by an unknown mechanism.60 | ||

| Clinical trials have all used the herb as part of a combination formula, whereby it reduces the frequency of symptomatic cough.61,62,94,156 | ||

| Proteolytic enzymes | Split the peptide bond of naked mucous glycoprotein when applied topically.25 | |

| Clinical trials are quite old, but demonstrate that bromelain may decrease: | ||

| Nasal irrigation | Nasal lavage with saline, or additional sodium hypochlorite, is well tolerated, with only minor side effects.49 | |

| It improves symptoms of: | ||

| Inhalation of essential oils | Much of the literature in this area is in German or Russian. | |

| Many plant constituents, especially essential oils, show marked antimicrobial activity.93,109,39 | ||

| Systemic review shows that topical antimicrobial agents appear effective in the treatment of chronic rhinosinusitis.160 | ||

| Trials demonstrate: | ||

Helms S., Miller A. Natural treatment of chronic rhinosinusitis. Altern Med Rev. 2006;11(3):196-207.

Cowan M.M. Plant products as antimicrobial agents. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1999;12(4):564-682.

Smit H.A., et al. Dietary influences on chronic obstructive lung disease and asthma: a review of the epidemiological evidence. Proc Nutr Soc. 1999;58(2):309-319.

1. Rubin M.G., et al. Infections of the upper respiratory tract. In: Fauci A.S., et al, editors. Harrison’s principles of internal medicine. New York: McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., 2008.

2. Piccirillo J.F. Clinical practice. Acute bacterial sinusitis. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(9):902-910.

3. Van Cauwenberge P., Watelet J.B. Epidemiology of chronic rhinosinusitis. Thorax. 2000;55(Suppl 2):S20-S21.

4. Celli B.R., MacNee W. Standards for the diagnosis and treatment of patients with COPD: a summary of the ATS/ERS position paper. Eur Respir J. 2004;23(6):932-946.

5. Rabe K.F., et al. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: GOLD executive summary. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;176(6):532-555.

6. National Asthma Education and Prevention Program. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of asthma. In: In: National Asthma Education and Prevention Program Expert Panel Report 3. Washington: National Insititutes of Health; 2007.

7. Han J.K., et al. Various causes for frontal sinus obstruction. Am J Otolaryngol. 2009;30(2):80-82.

8. Benjamin B. Sinusitis in children–general considerations. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 1983;5(3):281-284.

9. Spector S.L. The role of allergy in sinusitis in adults. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1992;90(3 Pt 2):518-520.

10. Helms S., Miller A. Natural treatment of chronic rhinosinusitis. Altern Med Rev. 2006;11(3):196-207.

11. Wuthrich B., et al. Milk consumption does not lead to mucus production or occurrence of asthma. J Am Coll Nutr. 2005;24(6):547S-555S. (Suppl)

12. Slavin R.G., et al. The diagnosis and management of sinusitis: a practice parameter update. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;116(6):S13-S47. (Suppl)

13. Lanza D.C., Kennedy D.W. Current concepts in the surgical management of chronic and recurrent acute sinusitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1992;90(3 Pt 2):505-510. discussion 511

14. Ahovuo-Saloranta A., et al. Antibiotics for acute maxillary sinusitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2):2008. CD000243

15. Rogers D.F. Mucoactive agents for airway mucus hypersecretory diseases. Respir Care. 2007;52(9):1176-1193. discussion 1193–1197

16. Wichtl M., editor. Herbal drugs and phytopharmaceuticals: a handbook for practice on a scientific basis, 3rd edn, Stuttgart: Medpharm GmbH Scientific Publishers, 2004.

17. Felter HW, Lloyd JU. King’s American dispensatory. Online. Available: http://www.henriettesherbal.com/eclectic/kings/extracta

18. Agency E.M. Community Monograph on Foeniculum vulgare. London: EMEA Committee on Herbal Medicinal Products; 2007.

19. Bone K.M. A clinical guide to blending liquid herbs. Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone; 2003.

20. Mittman P. Ask the experts. Severe recurring sinusitis. Explore (NY). 2005;1(6):495-496.

21. Blumenthal M., et al, editors. Herbal medicine: expanded Commission E Monographs (English translation). Austin: Integrative Medicine Communications, 2000.

22. Guo R., et al. Herbal medicines for the treatment of rhinosinusitis: a systematic review. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;135(4):496-506.

23. Grandjean E.M., et al. Efficacy of oral long-term N-acetylcysteine in chronic bronchopulmonary disease: a meta-analysis of published double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trials. Clin Ther. 2000;22(2):209-221.

24. Henke M.O., Ratjen F. Mucolytics in cystic fibrosis. Paediatr Respir Rev. 2007;8(1):24-29.

25. Majima Y. Mucoactive medications and airway disease. Paediatr Respir Rev. 2002;3(2):104-109.

26. Todisco T., et al. Effect of N-acetylcysteine in subjects with slow pulmonary mucociliary clearance. Eur J Respir Dis(Suppl). 1985;139:136-141.

27. Rautalahti M., et al. The effect of alpha-tocopherol and beta-carotene supplementation on COPD symptoms. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997;156(5):1447-1452.

28. Maurer H.R. Bromelain: biochemistry, pharmacology and medical use. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2001;58(9):1234-1245.

29. Castell J.V., et al. Intestinal absorption of undegraded proteins in men: presence of bromelain in plasma after oral intake. Am J Physiol. 1997;273(1 Pt 1):G139-G146.

30. Seltzer A.P. Adjunctive use of bromelains in sinusitis: a controlled study. Eye Ear Nose Throat Mon. 1967;46(10):1281-1288.

31. Ryan R.E. A double-blind clinical evaluation of bromelains in the treatment of acute sinusitis. Headache. 1967;7(1):13-17.

32. Taub S.J. The use of bromelains in sinusitis: a double-blind clinical evaluation. Eye Ear Nose Throat Mon. 1967;46(3):361-362. passim

33. Ophir D., Elad Y. Effects of steam inhalation on nasal patency and nasal symptoms in patients with the common cold. Am J Otolaryngol. 1987;8(3):149-153.

34. Tyrrell D., et al. Local hyperthermia benefits natural and experimental common colds. BMJ. 1989;298:1280-1283.

35. Forstall G., et al. Effect of inhaling heated vapor on symptoms of the common cold. JAMA. 1994;271(14):1109-1111.

36. Macknin M., et al. Effect of inhaling heated vapor on symptoms of the common cold. JAMA. 1990;264:989-991.

37. Saketkhoo K., et al. Effects of drinking hot water, cold water, and chicken soup on nasal mucus velocity and nasal airflow resistance. Chest. 1978;74(4):408-410.

38. Rennard B.O., et al. Chicken soup inhibits neutrophil chemotaxis in vitro. Chest. 2000;118(4):1150-1157.

39. Inouye S., et al. Screening of the antibacterial effects of a variety of essential oils on respiratory tract pathogens, using a modified dilution assay method. J Infect Chemother. 2001;7(4):251-254.

40. Burrows A. The effects of camphor, eucalyptus and menthol vapour on nasal resistance to airflow and nasal sensation. Acta Otolaryngol. 1983;96:157-163.

41. Shubina L., et al. [Inhalations of essential oils in the combined treatment of patients with chronic bronchitis]. Vrach Delo. 1990;5:66-67.

42. Food and Drug Administration. Over the counter drugs: monograph for OTC nasal decongestant drug products. Fed Reg. 1994;41:38408-38409.

43. Federspil P., et al. [Effects of standardized Myrtol in therapy of acute sinusitis–results of a double-blind, randomized multicenter study compared with placebo]. Laryngorhinootologie. 1997;76(1):23-27.

44. Pengelly A. The constituents of medicinal plants, 2nd edn. Crows Nest: Allen & Unwin; 2004.

45. Purchon N. Nerys Purchon’s handbook of aromatherapy, 2nd edn. Sydney: Hodder Headline; 1999. Australia

46. Yerushalmi A., et al. Treatment of perennial allergic rhinitis by local hyperthermia. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1982;79(15):4766-4769.

47. Elad Y., et al. Effects of elevated intranasal temperature on subjective and objective findings in perennial rhinitis. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1988;97(3):259-263.

48. Burton M.J., et al. Extracts from the Cochrane Library: Nasal saline irrigations for the symptoms of chronic rhinosinusitis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2007;137(4):532-534.

49. Harvey R., et al. Nasal saline irrigations for the symptoms of chronic rhinosinusitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (3):2007. CD006394

50. Jefferson W. The neti pot for better health. Summertown: Healthy Living Publications; 2005.

51. VanEs HA. Beginning yoga. Antioch: letsdoyoga.com.

52. Rabago D., et al. Efficacy of daily hypertonic saline nasal irrigation among patients with sinusitis: a randomized controlled trial. J Fam Pract. 2002;51(12):1049-1055.

53. Rhee C., et al. Effects of mucokinetic drugs on rheological properties of reconstituted human nasal mucus. Arch Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 1999;125:101-105.

54. Williams G.B., et al. Are bulb syringe irrigators a potential source of bacterial contamination in chronic rhinosinusitis? Am J Rhinol. 2008;22(4):399-401.

55. Ziment I. Herbal antitussives. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2002;15(3):327-333.

56. Gunn J. The action of expectorants. BMJ. 1927;2:972-975.

57. Mills S., Bone K. Principles and practice of phytotherapy. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 2000.

58. Kamei J., et al. Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic profiles of the antitussive principles of Glycyrrhizae radix (licorice), a main component of the Kampo preparation Bakumondo-to (Mai-men-dong-tang). Eur J Pharmacol. 2005;507(1–3):163-168.

59. Ernst E., et al. [Acute bronchitis: effectiveness of Sinupret. Comparative study with common expectorants in 3,187 patients] Fortschr Med. 1997;115(11):52-53.

60. Wienkotter N., et al. The effect of thyme extract on beta2-receptors and mucociliary clearance. Planta Med. 2007;73(7):629-635.

61. Kemmerich B. Evaluation of efficacy and tolerability of a fixed combination of dry extracts of thyme herb and primrose root in adults suffering from acute bronchitis with productive cough. A prospective, double-blind, placebo-controlled multicentre clinical trial. Arzneimittelforschung. 2007;57(9):607-615.

62. Kemmerich B., et al. Efficacy and tolerability of a fluid extract combination of thyme herb and ivy leaves and matched placebo in adults suffering from acute bronchitis with productive cough. A prospective, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Arzneimittelforschung. 2006;56(9):652-660.

63. Scientific Committee of the British Herbal Medical Association. British herbal pharmacopoeia. Bournemouth: British Herbal Medicine Association; 1983.

64. Deriu A., et al. Antimicrobial activity of Inula helenium L. essential oil against Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria and Candida spp. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2008;31(6):588-590.

65. Felter H.W. The eclectic materia medica. Pharmacology and therapeutics. 1922.

66. Nosal’ova G., et al. [Antitussive action of extracts and polysaccharides of marsh mallow (Althea officinalis L., var. robusta)]. Pharmazie. 1992;47(3):224-226.

67. Watt K., et al. The detection of antibacterial actions of whole herb tinctures using luminescent Escherichia coli. Phytother Res. 2007;21(12):1119-1193.

68. Dhuley J.N. Antitussive effect of Adhatoda vasica extract on mechanical or chemical stimulation-induced coughing in animals. J Ethnopharmacol. 1999;67(3):361-365.

69. Narimanian M., et al. Randomized trial of a fixed combination (KanJang) of herbal extracts containing Adhatoda vasica, Echinacea purpurea and Eleutherococcus senticosus in patients with upper respiratory tract infections. Phytomedicine. 2005;12(8):539-547.

70. Hasani A., et al. Effect of aromatics on lung mucociliary clearance in patients with chronic airways obstruction. J Altern Complement Med. 2003;9(2):243-249.

71. Morice A.H., et al. Effect of inhaled menthol on citric acid induced cough in normal subjects. Thorax. 1994;49(10):1024-1106.

72. Pauwels R.A., et al. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and World Health Organization Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD): executive summary. Respir Care. 2001;46(8):798-825.

73. Barnes P.J. Mechanisms in COPD: differences from asthma. Chest. 2000;117(2):10S-14S. (Suppl)

74. Radin A., Cote C. Primary care of the patient with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease – part 1: frontline prevention and early diagnosis. Am J Med. 2008;121(7):S3-S12. (Suppl)

75. White P. COPD: Challenges and opportunities for primary care. Respiratory Medicine: COPD Update. 2005;1:43-52.

76. Brug J., et al. Dietary change, nutrition education and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Patient Educ Couns. 2004;52(3):249-257.

77. Frankfort J.D., et al. Effects of high- and low-carbohydrate meals on maximum exercise performance in chronic airflow obstruction. Chest. 1991;100(3):792-795.

78. Angelillo V.A., et al. Effects of low and high carbohydrate feedings in ambulatory patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and chronic hypercapnia. Ann Intern Med. 1985;103(6 (Pt 1)):883-885.

79. Efthimiou J., et al. Effect of carbohydrate rich versus fat rich loads on gas exchange and walking performance in patients with chronic obstructive lung disease. Thorax. 1992;47(6):451-456.

80. Sadowska A.M., et al. Role of N-acetylcysteine in the management of COPD. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2006;1(4):425-434.

81. Stey C., et al. The effect of oral N-acetylcysteine in chronic bronchitis: a quantitative systematic review. Eur Respir J. 2000;16(2):253-262.

82. Meister R., et al. Efficacy and tolerability of myrtol standardized in long-term treatment of chronic bronchitis. A double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Study Group Investigators. Arzneimittelforschung. 1999;49(4):351-358.

83. Smit H.A., et al. Dietary influences on chronic obstructive lung disease and asthma: a review of the epidemiological evidence. Proc Nutr Soc. 1999;58(2):309-319.

84. Britton J., Knox A. Respiratory medicine. No cures but some advances. Lancet. 350(Suppl 3), 1997. SIII24

85. Celik F., Topcu F. Nutritional risk factors for the development of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in male smokers. Clin Nutr. 2006;25(6):955-961.

86. Hu G., Cassano P.A. Antioxidant nutrients and pulmonary function: the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III). Am J Epidemiol. 2000;151(10):975-981.

87. Fujimoto S., et al. Effects of coenzyme Q10 administration on pulmonary function and exercise performance in patients with chronic lung diseases. Clin Investig. 1993;71(8):S162-S166. Suppl

88. Bhatt S.P., et al. Serum magnesium is an independent predictor of frequent readmissions due to acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respir Med. 2008;102(7):999-1003.

89. Faeste C.K., et al. Allergenicityand antigenicity of fenugreek (Trigonella foenum-graecum) proteins in foods. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;123(1):187-194.

90. Maillard J.Y. Bacterial target sites for biocide action. Symp Ser Soc Appl Microbiol 2002(31):16S-27S.

91. Iten F., et al. Additive antimicrobial effects of the active components of the essential oil of Thymus vulgaris–chemotype Carvacrol. Planta Med. 2009. In press

92. Lopez-Lazaro M. Distribution and biological activities of the flavonoid luteolin. Mini Rev Med Chem. 2009;9(1):31-59.

93. Fabio A., et al. Screening of the antibacterial effects of a variety of essential oils on microorganisms responsible for respiratory infections. Phytother Res. 2007;21(4):374-377.

94. Marzian O. [Treatment of acute bronchitis in children and adolescents. Non-interventional postmarketing surveillance study confirms the benefit and safety of a syrup made of extracts from thyme and ivy leaves]. MMW Fortschr Med. 2007;149(11):69-74.

95. Stojakowska A., et al. Thymol derivatives from a root culture of Inula helenium. Z Naturforsch C. 2004;59(7–8):606-608.

96. Miskovsky P. Hypericin – a new antiviral and antitumor photosensitizer: mechanism of action and interaction with biological macromolecules. Curr Drug Targets. 2002;3(1):55-84.

97. Bodinet C., et al. Effect of oral application of an immunomodulating plant extract on Influenza virus type A infection in mice. Planta Med. 2002;68(10):896-900.

98. Low Dog T. A reason to season: the therapeutic benefits of spices and culinary herbs. Explore (NY). 2006;2(5):446-449.

99. Zhen H., et al. Experimental study on the action of allitridin against human cytomegalovirus in vitro: Inhibitory effects on immediate-early genes. Antiviral Res. 2006;72(1):68-74.

100. Adeleye I.A., Opiah L. Antimicrobial activity of extracts of local cough mixtures on upper respiratory tract bacterial pathogens. West Indian Med J. 2003;52(3):188-190.

101. Luo D.Q., et al. Anti-fungal efficacy of polybutylcyanoacrylate nanoparticles of allicin and comparison with pure allicin. J Biomater Sci Polym Ed. 2009;20(1):21-31.

102. Liu Z.F., et al. Experimental study on the prevention and treatment of murine cytomegalovirus hepatitis by using allitridin. Antiviral Res. 2004;61(2):125-128.

103. Hiltunen R., et al. Preventing airborne infection with an intranasal cellulose powder formulation (Nasaleze travel). Adv Ther. 2007;24(5):1146-1153.

104. Amin M., Kapadnis B.P. Heat stable antimicrobial activity of Allium ascalonicum against bacteria and fungi. Indian J Exp Biol. 2005;43(8):751-754.

105. Al-Waili N.S., et al. Effects of heating, storage, and ultraviolet exposure on antimicrobial activity of garlic juice. J Med Food. 2007;10(1):208-212.

106. Osato J.A., et al. Antimicrobial and antioxidant activities of unripe papaya. Life Sci. 1993;53(17):1383-1389.

107. Jones N., et al. Antibacterial activity of ZnO nanoparticle suspensions on a broad spectrum of microorganisms. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2008;279(1):71-76.

108. Djokic S. Synthesis and antimicrobial activity of silver citrate complexes. Bioinorg Chem Appl. 2008:436-458.

109. Cowan M.M. Plant products as antimicrobial agents. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1999;12(4):564-582.

110. Peres M.T., et al. Chemical composition and antimicrobial activity of Croton urucurana Baillon (Euphorbiaceae). J Ethnopharmacol. 1997;56(3):223-226.

111. Toda M., et al. The protective activity of tea catechins against experimental infection by Vibrio cholerae O1. Microbiol Immunol. 1992;36(9):999-1001.

112. Castillo-Juarez I., et al. Anti-Helicobacter pylori activity of anacardic acids from Amphipterygium adstringens. J Ethnopharmacol. 2007;114(1):72-77.

113. Alves D.S., et al. Membrane-related effects underlying the biological activity of the anthraquinones emodin and barbaloin. Biochem Pharmacol. 2004;68(3):549-561.

114. Perrett S., et al. The plant molluscicide Millettia thonningii (Leguminosae) as a topical antischistosomal agent. J Ethnopharmacol. 1995;47(1):49-54.

115. Rojas A., et al. Screening for antimicrobial activity of crude drug extracts and pure natural products from Mexican medicinal plants. J Ethnopharmacol. 1992;35(3):275-283.

116. Brinkworth R.I., et al. Flavones are inhibitors of HIV-1 proteinase. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1992;188(2):631-637.

117. Sookkongwaree K., et al. Inhibition of viral proteases by Zingiberaceae extracts and flavones isolated from Kaempferia parviflora. Pharmazie. 2006;61(8):717-721.

118. Ono K., et al. Inhibition of reverse transcriptase activity by a flavonoid compound, 5,6,7-trihydroxyflavone. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1989;160(3):982-987.

119. Taniguchi M., Kubo I. Ethnobotanical drug discovery based on medicine men’s trials in the African savanna: screening of east African plants for antimicrobial activity II. J Nat Prod. 1993;56(9):1539-1546.

120. Li M., Xu Z. Quercetin in a lotus leaves extract may be responsible for antibacterial activity. Arch Pharm Res. 2008;31(5):640-644.

121. Cushnie T.P., et al. Aggregation of Staphylococcus aureus following treatment with the antibacterial flavonol galangin. J Appl Microbiol. 2007;103(5):1562-1567.

122. Haslam E. Natural polyphenols (vegetable tannins) as drugs: possible modes of action. J Nat Prod. 1996;59(2):205-215.

123. Tomczyk M., Latte K.P. Potentilla–a review of its phytochemical and pharmacological profile. J Ethnopharmacol. 2009;122(2):184-204.

124. Cichewicz R.H., Thorpe P.A. The antimicrobial properties of chile peppers (Capsicum species) and their uses in Mayan medicine. J Ethnopharmacol. 1996;52(2):61-70.

125. Atta-ur R., Choudhary M.I. Diterpenoid and steroidal alkaloids. Nat Prod Rep. 1995;12(4):361-379.

126. Freiburghaus F., et al. Evaluation of African medicinal plants for their in vitro trypanocidal activity. J Ethnopharmacol. 1996;55(1):1-11.

127. Houghton P.J., et al. Antiviral activity of natural and semi-synthetic chromone alkaloids. Antiviral Res. 1994;25(3–4):235-244.

128. Meyer J.J., et al. Antiviral activity of galangin isolated from the aerial parts of Helichrysum aureonitens. J Ethnopharmacol. 1997;56(2):165-169.

129. Zhang Y., Lewis K. Fabatins: new antimicrobial plant peptides. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1997;149(1):59-64.

130. Kokoska L., Janovska D. Chemistry and pharmacology of Rhaponticum carthamoides: A review. Phytochemistry. 2009;70(7):842-855.

131. Bachert C., et al. Treatment of acute rhinosinusitis with the preparation from Pelargonium sidoides EPs 7630: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Rhinology. 2009;47(1):51-58.

132. Lizogub V.G., et al. Efficacy of a pelargonium sidoides preparation in patients with the common cold: a randomized, double blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Explore (NY). 2007;3(6):573-584.

133. Heuser G., Vojdani A. Enhancement of natural killer cell activity and T and B cell function by buffered vitamin C in patients exposed to toxic chemicals: the role of protein kinase-C. Immunopharmacol Immunotoxicol. 1997;19(3):291-312.

134. Murray M.T. A comprehensive review of Vitamin C. American Journal of Natural Medicine. 1996;3:8-21.

135. Unal M., et al. Serum levels of antioxidant vitamins, copper, zinc and magnesium in children with chronic rhinosinusitis. J Trace Elem Med Biol. 2004;18(2):189-192.

136. Podoshin L., et al. Treatment of perennial allergic rhinitis with ascorbic acid solution. Ear Nose Throat J. 1991;70(1):54-55.

137. Flamand N., et al. Histamine-induced inhibition of leukotriene biosynthesis in human neutrophils: involvement of the H2 receptor and cAMP. Br J Pharmacol. 2004;141(4):552-561.

138. Mittman P. Randomized, double-blind study of freeze-dried Urtica dioica in the treatment of allergic rhinitis. Planta Med. 1990;56(1):44-47.

139. Demling R.H. Nutrition, anabolism, and the wound healing process: an overview. Eplasty. 2009;9:e9.

140. Barbul A., Purtill W.A. Nutrition in wound healing. Clin Dermatol. 1994;12(1):133-140.

141. Ross A.C., Ternus M.E. Vitamin A as a hormone: recent advances in understanding the actions of retinol, retinoic acid, and beta carotene. J Am Diet Assoc. 1993;93(11):1285-1290. quiz 1291–1292

142. Osiecki H. The nutrient bible, 6th edn. Eagle Farm: Bio concepts Publishing; 2004.

143. Kohlmeier M. Nutrient metabolism. Oxford: Elsevier; 2003.

144. McCullough F.S., et al. The effect of vitamin A on epithelial integrity. Proc Nutr Soc. 1999;58(2):289-293.

145. Donesky-Cuenco D., et al. Yoga therapy decreases dyspnea-related distress and improves functional performance in people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a pilot study. J Altern Complement Med. 2009;15(3):225-234.

146. Pomidori L., et al. Efficacy and tolerability of yoga breathing in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a pilot study. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev. 2009;29(2):133-137.

147. Lee M.S., et al. Acupuncture for allergic rhinitis: a systematic review. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2009;102(4):269-279. quiz 279–281, 307

148. Fleckenstein J., et al. Impact of acupuncture on vasomotor rhinitis: a randomized placebo-controlled pilot study. J Altern Complement Med. 2009;15(4):391-398.

149. Suzuki M., et al. The effect of acupuncture in the treatment of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Altern Complement Med. 2008;14(9):1097-1105.

150. Jobst K., et al. Controlled trial of acupuncture for disabling breathlessness. Lancet. 1986;2(8521–28522):1416-1419.

151. Lau K.S., Jones A.Y. A single session of Acu-TENS increases FEV1 and reduces dyspnoea in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Aust J Physiother. 2008;54(3):179-184.

152. Wilkinson I.S., et al. A randomised-controlled trial examining the effects of reflexology of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2006;12(2):141-147.

153. Beeken J.E., et al. The effectiveness of neuromuscular release massage therapy in five individuals with chronic obstructive lung disease. Clin Nurs Res. 1998;7(3):309-325.

154. Sheffner A.L., et al. The in vitro reduction in viscosity of human tracheobronchial secretions by acetylcysteine. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1964;90:721-729.

155. Sadowska A.M., et al. Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory efficacy of NAC in the treatment of COPD: discordant in vitro and in vivo dose-effects: a review. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2007;20(1):9-22.

156. Buechi S., et al. Open trial to assess aspects of safety and efficacy of a combined herbal cough syrup with ivy and thyme. Forsch Komplementarmed Klass Naturheilkd. 2005;12(6):328-332.

157. Rabago D., et al. The efficacy of hypertonic saline nasal irrigation for chronic sinonasal symptoms. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2005;133(1):3-8.

158. Rabago D., et al. Qualitative aspects of nasal irrigation use by patients with chronic sinus disease in a multimethod study. Ann Fam Med. 2006;4(4):295-301.

159. Raza T., et al. Nasal lavage with sodium hypochlorite solution in Staphylococcus aureus persistent rhinosinusitis. Rhinology. 2008;46(1):15-22.

160. Lim M., et al. Topical antimicrobials in the management of chronic rhinosinusitis: a systematic review. Am J Rhinol. 2008;22(4):381-389.

161. Matthys H., et al. Efficacy and tolerability of myrtol standardized in acute bronchitis. A multi-centre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled parallel group clinical trial vs. cefuroxime and ambroxol. Arzneimittelforschung. 2000;50(8):700-711.