Congenital Vaginal Abnormalities

Imperforate Hymen

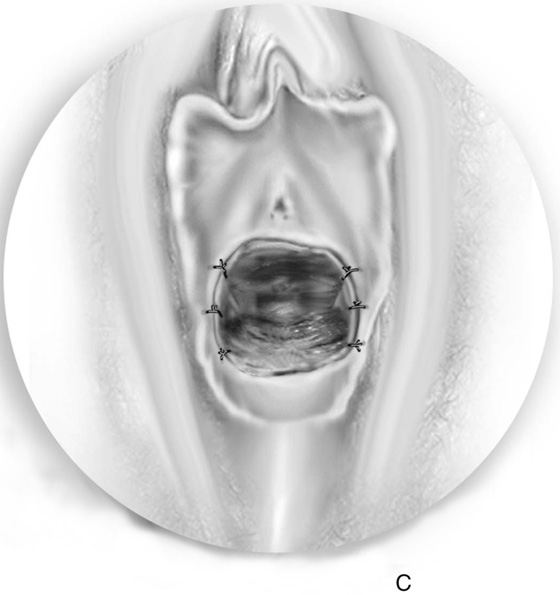

A child or adolescent with an imperforate hymen presents with pain and a thin, translucent membrane distended by blood or mucus. An imperforate hymen is often treated in the operating suite with sedation or general anesthesia.

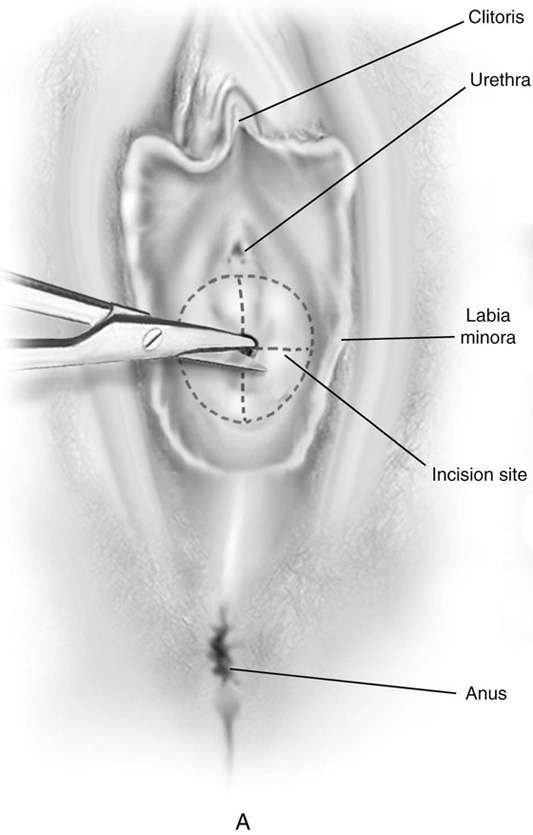

First, an incision is made in the center of the membrane, and the blood and mucus are evacuated. The incision is extended transversely to the lateral margins of the obstructing membrane (Fig. 61–1A, B). Next, the membrane is divided anteriorly, then posteriorly, to complete a cruciate incision. Finally, the redundant avascular tissue is excised (Fig. 61–1C).

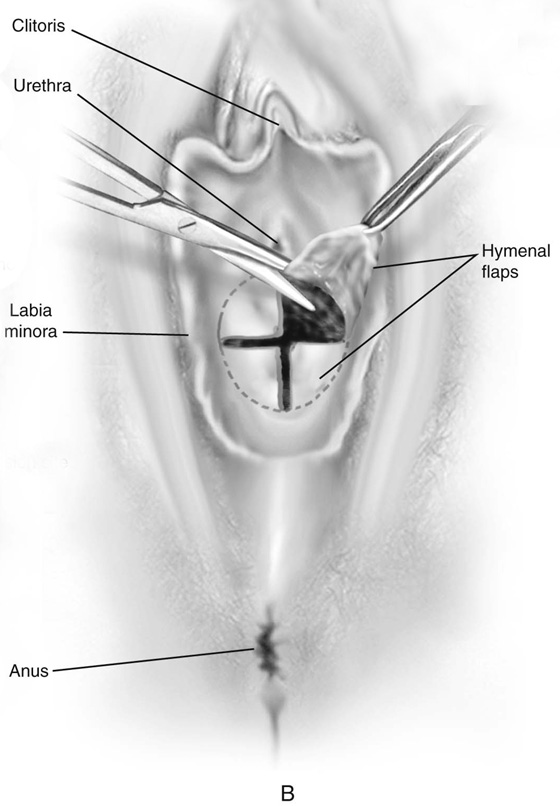

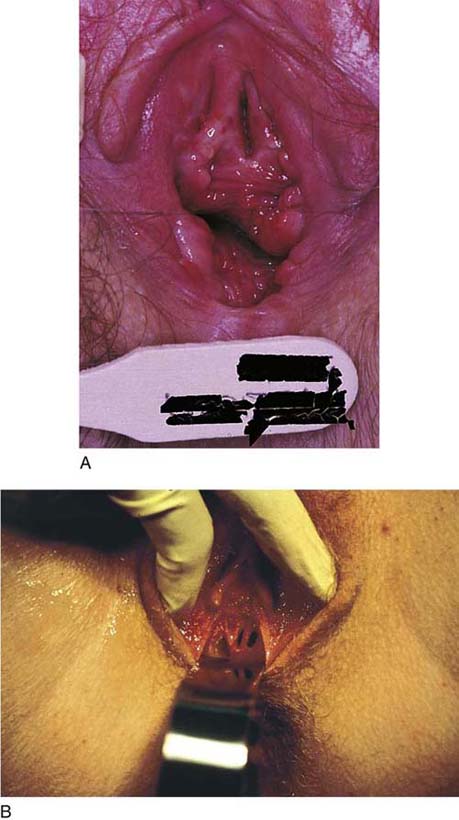

Bleeding should be minimal following resection of the hymenal membrane. Pressure applied with a damp sponge will control most bleeding sites. If the resection has been carried out too far, and the bleeding cannot be controlled with a sparing application of Monsel’s solution (ferric subsulfate) or light pressure, then simple interrupted sutures of 3-0 polyglycolic acid should be placed. A continuous running simple suture should be avoided because this may cause constriction of the hymenal ring. The appropriate result is a capacious introitus that functionally permits comfortable coitus (Fig. 61–2A).

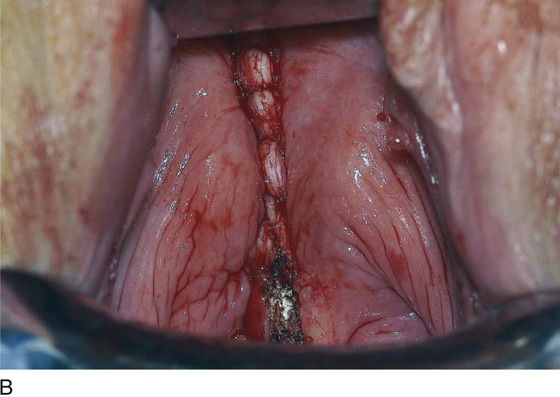

Other developmental abnormalities of the hymen, including cribriform and septated hymens (Fig. 61–2B), may require surgical intervention. As with the aforementioned, the goal of the surgery is to create a nonconstricting, functional vaginal introitus.

FIGURE 61–1 A. The incision is extended laterally into the hymenal membrane from 3 to 9 o’clock, then along the midline from 12 to 6 o’clock. B. Resection of the hymenal membrane is completed as the avascular quadrants are excised. C. The hymenal flaps have been resected, and the areas between 1 and 5 o’clock and between 11 and 7 o’clock have been sutured to the vestibular margin with interrupted 3-0 Vicryl sutures.

FIGURE 61–2 A. Eight weeks after resection of the hymen. The introitus is widely open. The patient has been inserting a large vaginal form for 4 weeks. B. This young woman has a cribriform hymen. It is excised in a manner similar to the imperforate hymen (see Fig. 61–1A through C).

Vaginal Agenesis

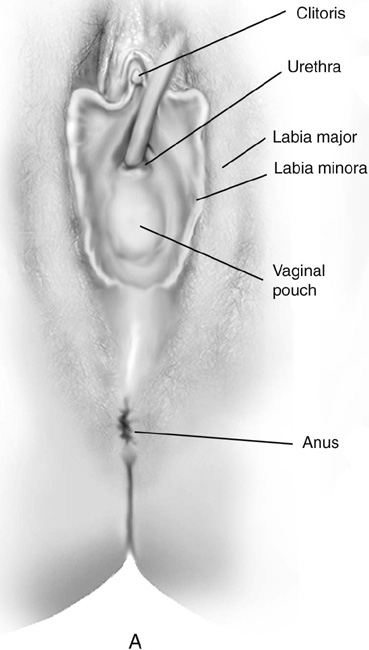

Müllerian agenesis occurs once in approximately 4000 to 5000 female births. Typical findings of Rokitansky-Kuster-Hauser syndrome include a small vaginal pouch and a normal perineum (Fig. 61–3A). Vaginal agenesis may also occur in a male pseudohermaphrodite. Genital appearance varies depending on the underlying causes. Occasionally, a “flat” perineum is found (Fig. 61–3B).

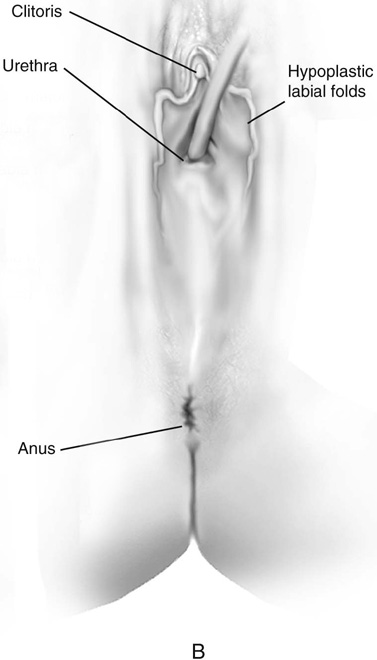

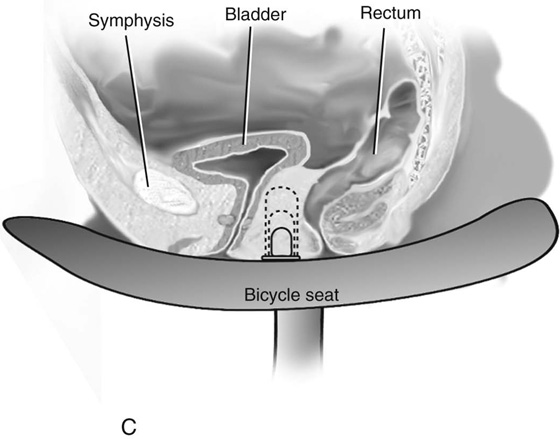

Vaginal dilation using the Ingram method is the primary approach used to prepare the vagina for intercourse when a vaginal pouch is present. A series of progressively wider and longer dilators are used (Fig. 61–3C). The patient is instructed to position the dilator against the perineum, and to apply her weight gradually onto a bicycle seat that is affixed to a stool. In a motivated patient, the vagina can be prepared for intercourse after a few weeks of dilation. More than 90% of women who comply with this regimen achieve anatomic and functional success.

The McIndoe vaginoplasty is the primary surgical approach for vaginal agenesis when dilation is unsuccessful or is not possible. The patient must be physically and emotionally prepared for the surgery and must anticipate intercourse in the not too distant future.

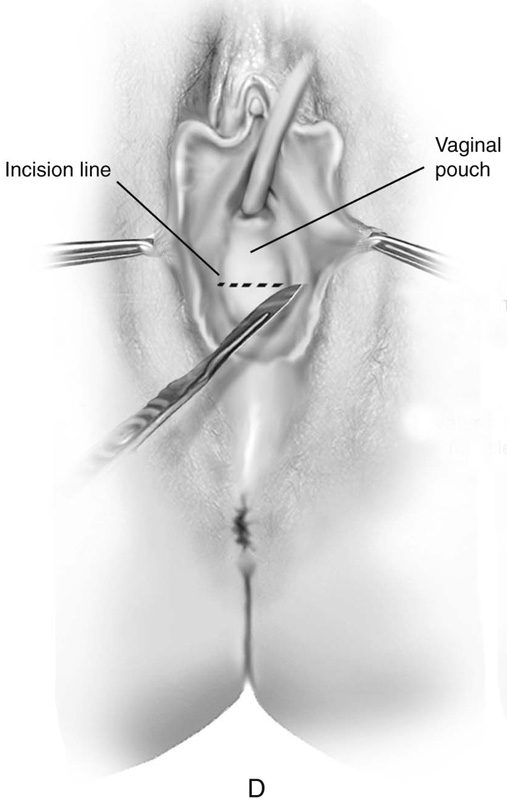

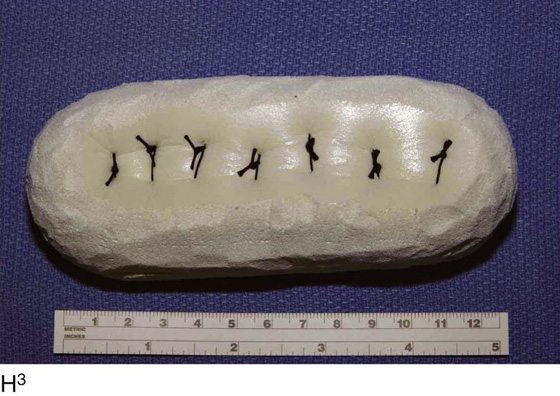

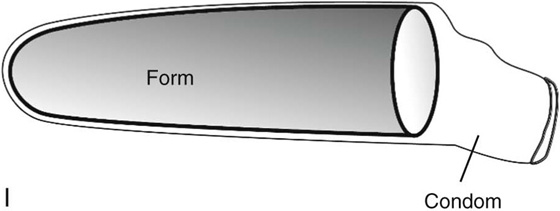

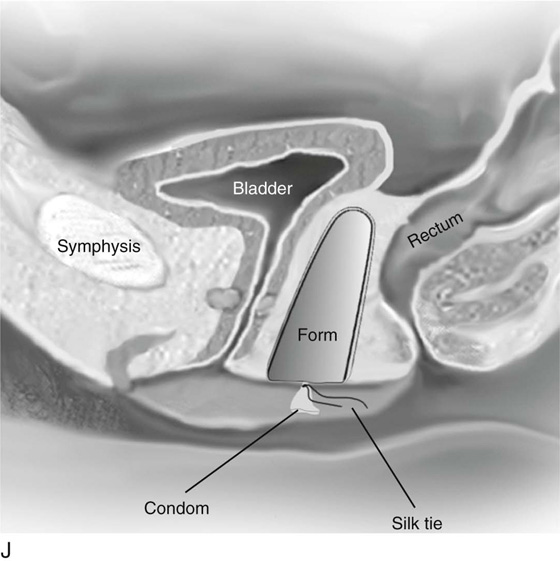

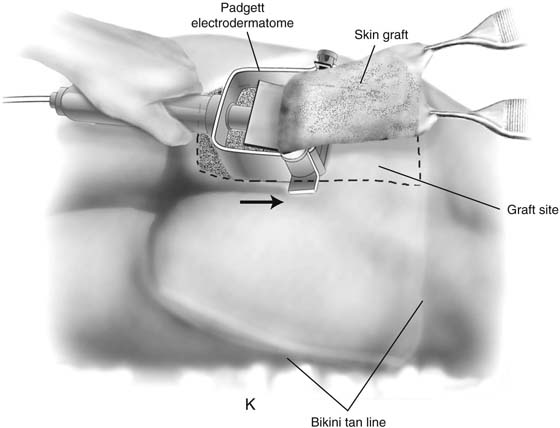

FIGURE 61–3 A. Müllerian agenesis. The perineum is normal. A small vaginal pouch is evident. B. A flat perineum, which may be found in a male pseudohermaphrodite. No vaginal pouch is present. Labial folds, if present, terminate near the urethral meatus. C. Vaginal dilation with graduated dilators. Using a bicycle seat, the patient slowly sits on the dilator. Pressure on the dilator from the body’s weight allows complete dilation within a few weeks. D. Initial transverse incision into the apex of the vaginal pouch in a woman with vaginal agenesis. The initial incision should be at least 3 to 4 cm. E. Initial transverse incision is made immediately anterior to the superficial transverse peroneal muscle in the patient with a flat perineum. Relationships among the urethra, labia, rectum, and underlying musculature are shown. F. Blunt dissection into the neovaginal space. Dissection is performed laterally, then medially. If the patient is 46XY, sharp resection of the prostate may be necessary to avoid damage to the rectal mucosa. Care is taken not to dissect too large an area near the peritoneum because herniation may occur. G. Retractors are placed into the neovaginal space. The median raphe, a thick band of connective tissue, is divided sharply. H. A 10 × 10 × 20-cm sterile block of soft foam rubber is shaped according to the outline. The base is cut to accommodate the vaginal depth. The cut end is saved and later is used to protect the neovagina. I. A sterile condom is placed over the shaped vaginal form. J. After the form and the condom have been compressed, they are placed into the neovaginal space and allowed to expand for approximately 1 minute. A 2-0 silk tie is then secured at the base of the condom, and the form is removed. A second condom is placed over the first condom, and the base tied with 2-0 silk. K. The patient is placed in a lateral position. The buttock is prepped and draped, then is coated with sterile mineral oil. A Padgett electrodermatome with a 10-cm-wide blade is used to harvest a 0.45-mm-thick graft 15 to 18 cm long inside the bikini (tan) line if possible. L. The edges of the graft are approximated around the form with interrupted vertical mattress sutures of 5-0 polyglycolic acid. The skin surface touches the form. M. The form and the covering graft are placed into the neovaginal space. The edges of the graft are sutured to the perineal skin with interrupted absorbable suture material, approximately 1 cm apart, to allow drainage. N. A foam pad is placed over the perineum and is secured into the labia minora with 0 silk suture. A gap is cut near the anus to avoid contamination of the pad during a bowel movement. O. Instruments required for the Vecchietti vaginoplasty include a 2.2 × 1.9-cm acrylic “olive,” an abdominal traction device, a long perineum suture passer, and an alligator-jaw needle passer. P. A #2 polyglycolic acid suture is passed through the olive, and both free ends of the suture are placed in a long needle passer. Q. A laparoscope is placed through the umbilicus, and a secondary port is inserted above the symphysis. Concurrent cystoscopy is performed, and one finger is placed into the rectum to identify puncture of the bladder or bowel. The long needle passer is inserted from the perineum into the peritoneal cavity under direct laparoscopic visualization. A suture passer is placed through the skin into the abdomen in the right lower quadrant, approximately 2 to 3 cm above the symphysis. One end of the suture is grasped and pulled through the skin. This procedure is repeated through the left lower quadrant, so that both ends of the suture are removed through the abdomen. R. The sutures are attached to the Vecchietti device, and traction is applied to allow downward movement of the olive of 1 cm with countertraction. Tension should be equal on both sides of the device. Within 7 to 9 days, a 10- to 12-cm vagina is created.

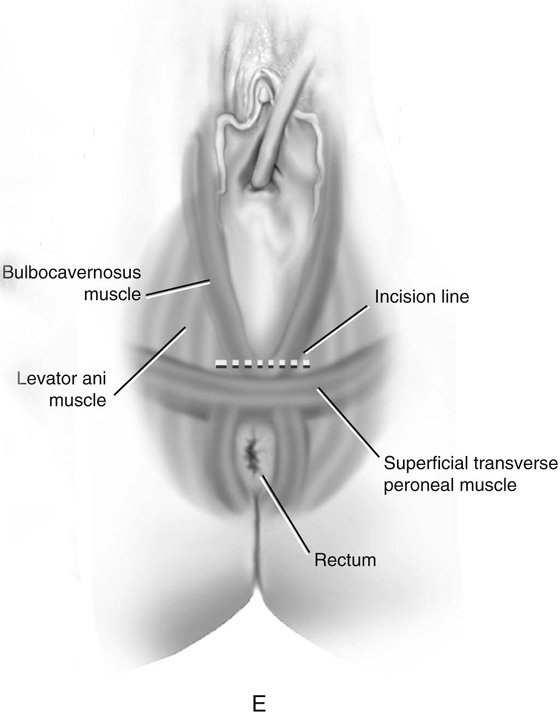

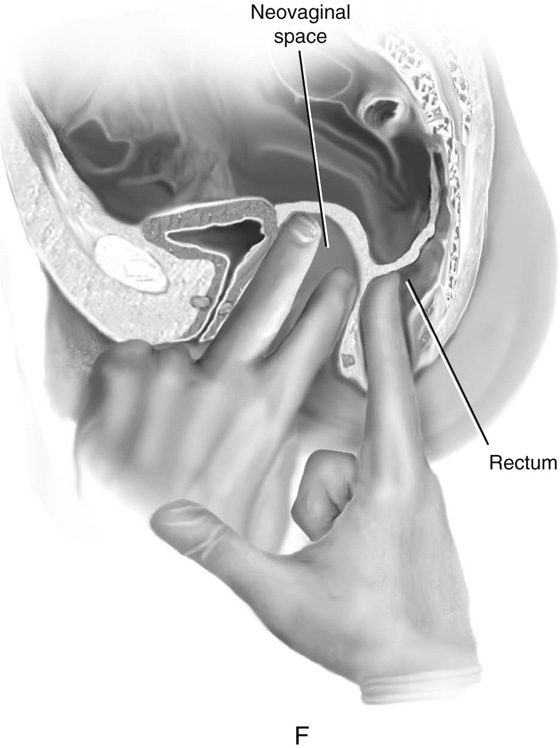

First, a transverse incision is made at the apex of the vaginal pouch in the patient with müllerian agenesis (Fig. 61–3D). If the perineum is flat, a 3- to 4-cm incision is made in the posterior fourchette, anterior to the anal sphincter (Fig. 61–3E). The neovaginal space is bluntly dissected laterally, then toward the midline. One finger is placed in the rectum for guidance (Fig. 61–3F).

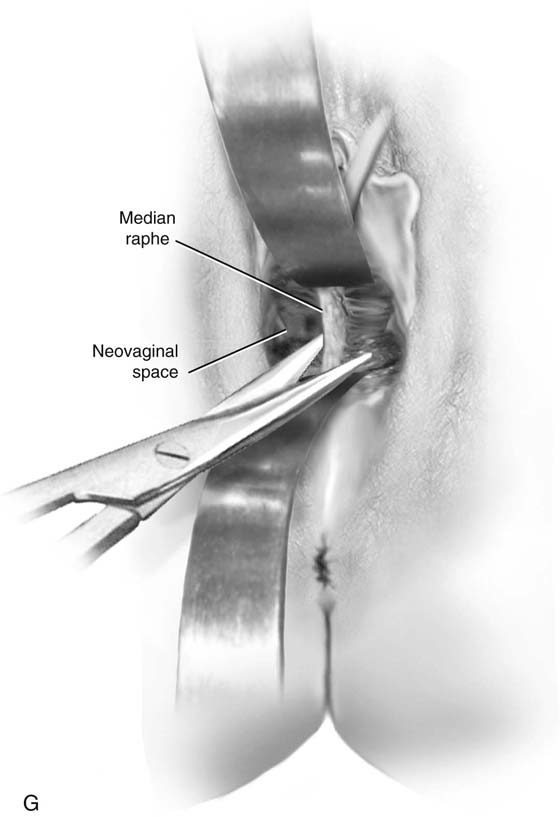

Sharp dissection is necessary in the male pseudohermaphrodite if the prostate remnant is adherent to the rectum. A thick band of connective tissue between the bladder and rectum—the median raphe—is sharply divided near the neovaginal fornix (Fig. 61–3G). The space should easily accommodate the surgeon’s index and middle fingers. If necessary, the levator muscles can be divided lateral to the incision to provide more space. Meticulous hemostasis is obtained.

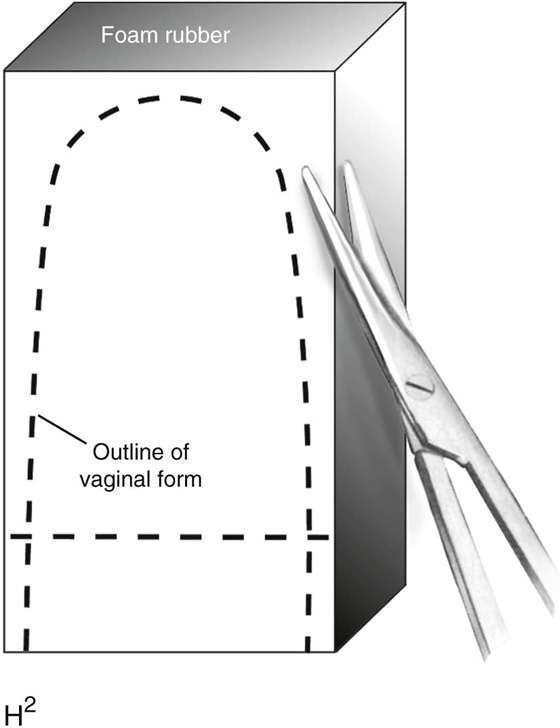

Next, sterile 10 × 10 × 20-cm foam rubber form is shaped with scissors (Fig. 61–3H). The form is placed inside a sterile condom and compressed (Fig. 61–3I). The compressed form is inserted completely into the neovaginal space (Fig. 61–3J). The form is then allowed to expand for 1 to 2 minutes. The external end of the condom is tied with a silk suture and the form removed. A second condom is placed over the form, and the free end is tied with a silk suture.

Next, a split-thickness skin graft is harvested. The patient is repositioned into a lateral position. After the harvest site is cleaned, sterile mineral oil is applied to the buttock. A 10-cm Padgett electrodermatome blade, set at 0.017 inch (0.45 mm), is used to obtain a 15- to 18-cm graft from the buttock inside the bikini (tan) line if possible (Fig. 61–3K). The graft site is covered with a sterile plastic adhesive sheet. The patient is then placed back in the lithotomy position.

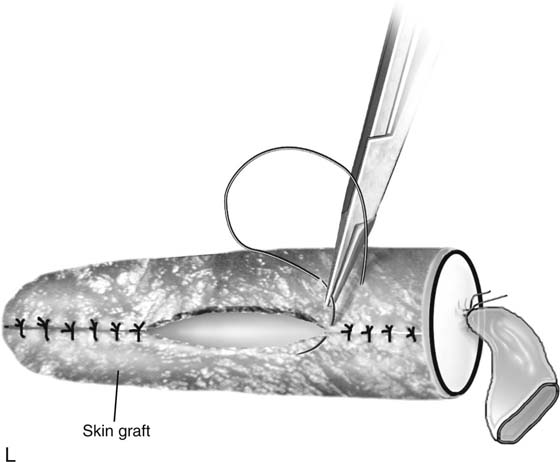

Interrupted 5-0 absorbable nonreactive sutures are used to sew the graft over the vaginal form with the skin surface touching the form (Fig. 61–3L). During preparation of the graft, a suprapubic catheter is placed in the urinary bladder. The suprapubic catheter prevents pressure necrosis on the graft, which may occur with a urethral Foley catheter.

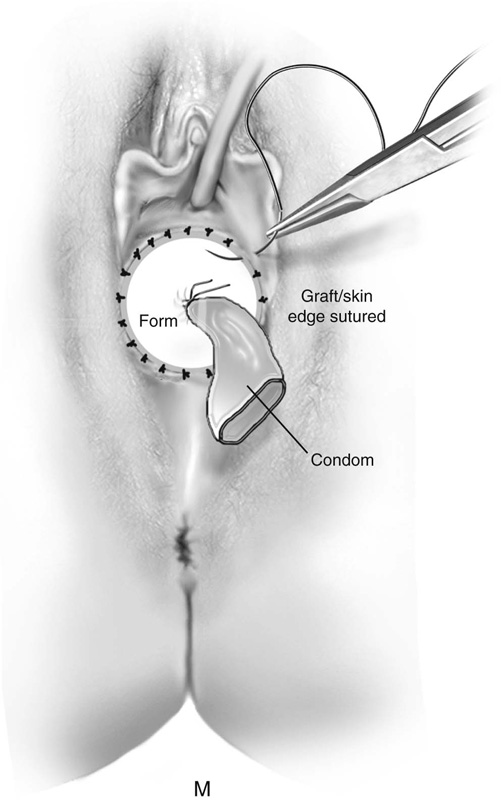

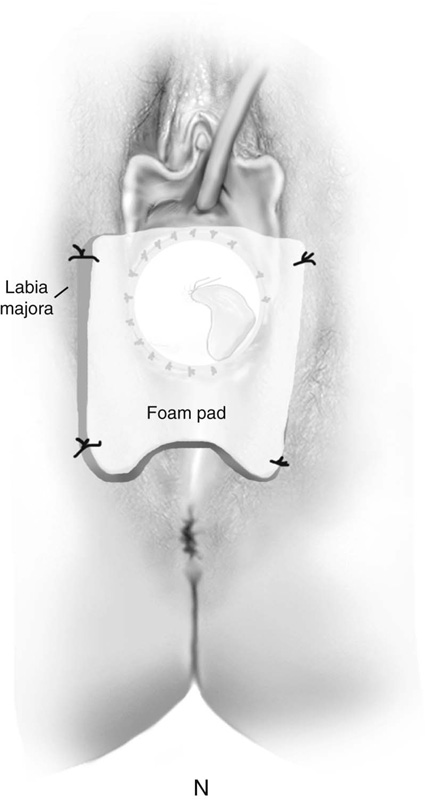

After the edges are sutured, the graft and form are placed in the neovaginal space. The graft edges are sutured to the skin edges with 5-0 polyglycolic acid, allowing approximately 1 cm between suture sites to provide drainage of blood or serous fluid (Fig. 61–3M). A supporting foam pad is placed over the perineum and is anchored into place with labial sutures (Fig. 61–3N).

Postoperatively, the patient is kept on strict bedrest for 1 week. A constipating regimen of diphenoxylate-atropine (Lomotil) or codeine is prescribed, along with a low-residue diet. The patient is allowed to log roll but should be moved as a single unit to prevent “shearing” of the graft from the neovaginal walls. Pneumatic compression stockings are worn during the entire postoperative interval. Patient-controlled analgesia, administered by an epidural catheter placed preoperatively, provides for additional comfort and may improve compliance with bedrest.

After 1 week, the patient is brought back to the operating room. The vaginal form is removed and the vagina irrigated. The suprapubic catheter is removed. The graft is carefully inspected to assess viability. Small nonviable areas can be excised and allowed to heal by granulation. However, repeat skin grafting is necessary with large necrotic areas or total failure of the graft.

Postoperative compliance with dilation is essential. The form is removed daily to allow a warm-water douche. It is worn continuously for 2 to 4 weeks, then is used nightly. After healing is complete, rigid dilation may be necessary until the patient initiates sexual activity. Intercourse may be possible 4 to 8 weeks after surgery. Approximately 80% of women report long-term satisfaction after McIndoe vaginoplasty. Ninety percent are sexually active, and 75% are able to achieve orgasm.

Several alternatives to skin grafting have been proposed, including barrier products to prevent adhesions (Interceed), artificial dermis, autologous buccal mucosa, and simply allowing the neovaginal space to heal by secondary intention. The adhesion barrier is used to cover the vaginal form after creation of the neovaginal space, and skin grafting is avoided. However, we have seen severe contracture and scarring of the neovagina in a patient referred after this approach, and these alternatives cannot be recommended.

The Vecchietti procedure is a surgical alternative to passive dilation and the McIndoe vaginoplasty and is the preferred approach in some European centers. The Vecchietti procedure is performed by placing progressive tension on abdominal sutures that are attached to an olive-shaped device at the perineum. This method was originally performed during laparotomy, but a laparoscopic approach provides comparable outcomes and a faster recovery.

Like the McIndoe vaginoplasty, the Vecchietti procedure should be performed only when passive dilation is unsuccessful, and when the patient is physically and emotionally prepared for the surgery and anticipates intercourse in the not too distant future. However, it may be considered a primary approach if laparoscopy or laparotomy is required for other indications such as pelvic pain.

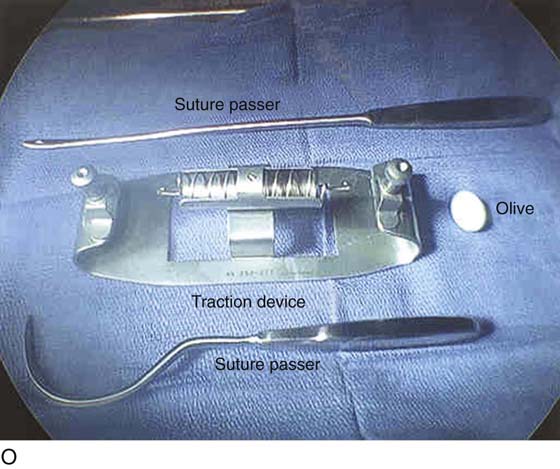

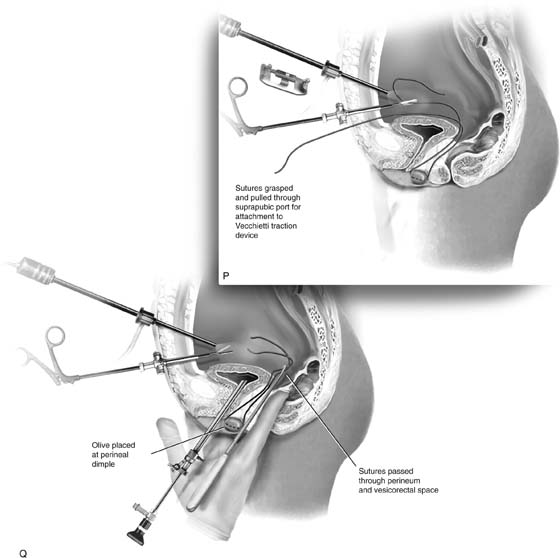

Special instruments required for the Vecchietti procedure include a 2.2 × 1.9-cm acrylic “olive,” an abdominal traction device, and a long perineum suture passer (Fig. 61–3O). An alligator-jaw needle passer is also helpful. The laparoscope is placed through the umbilicus. An additional port is placed approximately 2 to 3 cm above the symphysis. A #2 polyglycolic acid suture is passed through the olive, and both free ends of the suture are placed in a long needle passer (Fig. 61–3P). Concurrent cystoscopy is performed, and one finger is placed in the rectum to ensure that the bladder and the bowel are not punctured during the procedure. The long needle is inserted through the perineum and the vesicorectal space into the peritoneal cavity under direct laparoscopic visualization (Fig. 61–3Q). The free ends of the suture are removed from the needle with graspers placed through the suprapubic port, and the needle is removed from the perineum.

The Vecchietti traction device is placed 2 to 3 cm above the symphysis, and a marking pen is used to identify the sites in the right and left lower quadrants where the sutures will be passed through the abdominal wall (see Fig. 61–3Q). The traction device is removed temporarily, and a needle passer is placed through the marked skin into the abdomen. One end of the suture is grasped with the needle passer, and the suture is pulled through the skin (see Fig 61–3Q). This procedure is repeated through the left lower quadrant, so that both ends of the suture are removed through the abdomen.

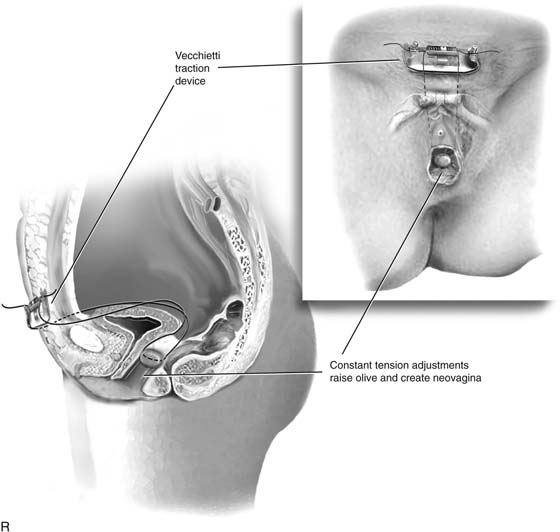

The sutures are attached to the Vecchietti traction device (Fig 61–3R). Traction is applied to allow downward movement of the olive of 1 cm with countertraction. Tension should be equal on both sides of the device. Excessive traction may cause tissue necrosis, and inadequate traction will not accomplish vaginal lengthening.

Patients are hospitalized for 2 to 3 days, then are seen every day or every other day after discharge until adequate depth has been attained. Tension on the traction sutures is adjusted every 24 to 48 hours, at a maximal daily rate of 1.0 to 1.5 cm. Using constant pressure allows creation of a 7- to 10-cm vagina within 7 to 9 days in most cases. Early ambulation is believed to accelerate vaginal dilation by increasing traction on the olive with contraction of the rectus muscles.

All patients require analgesics for perineal pain as suture tension is increased. A serosanguineous discharge related to tension on the olive is normal during this stage.

The sutures are removed during heavy sedation or general anesthesia after vaginal dilation of at least 7 cm is achieved. Postoperatively, a soft latex 1.5-cm-diameter, 10-cm dilator is used continuously for approximately 8 to 10 hours daily during the first month. The patient gradually advances to larger dilators, first 2.0 cm followed by 2.5 cm. Intercourse may be allowed beginning 20 days after the olive is removed. Long-term sexual satisfaction is greater than 80% with this approach, which is comparable with passive dilation and the McIndoe vaginoplasty.

Transverse Vaginal Septum

The patient with a transverse vaginal septum typically presents with progressive pain and amenorrhea at the time of expected menses. Examination reveals a normal perineum, a blind vaginal pouch, and a palpable mass (the hematocolpos) during rectal examination.

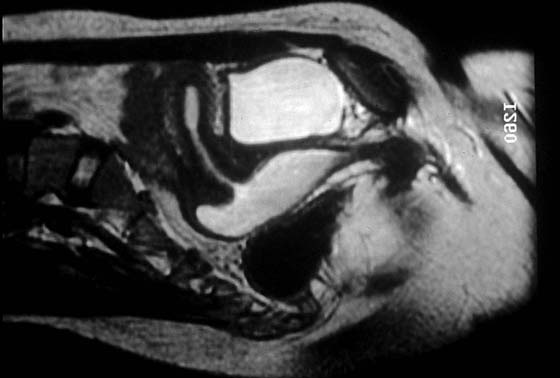

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) should be done before surgery to determine the extent of the transverse vaginal septum, to confirm the presence of the cervix, and to evaluate the uterus (Fig. 61–4). Surgical resection of the septum is usually necessary soon after the diagnosis is established.

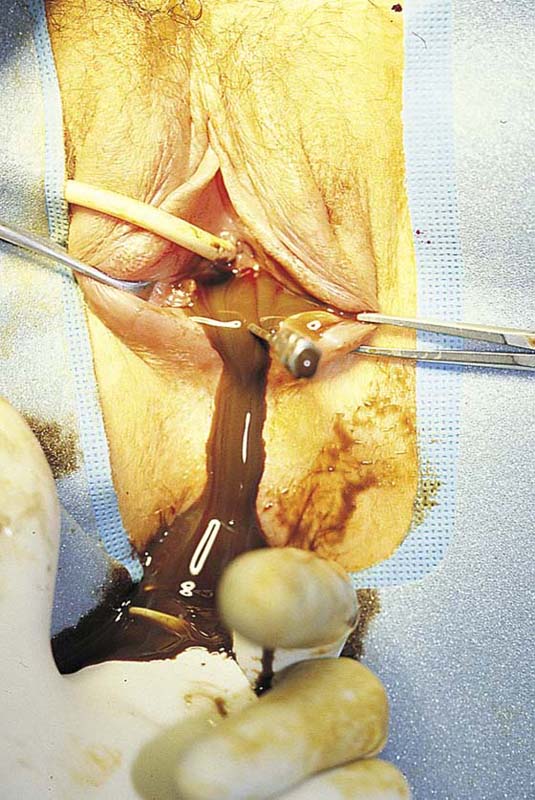

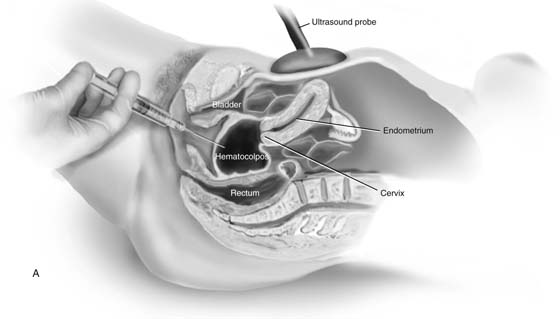

Temporizing measures to relieve pain and reduce the hematocolpos may be beneficial if MRI confirms a high transverse vaginal septum. The hematocolpos can be evacuated in the operating room under abdominal ultrasonographic guidance. After prophylactic antibiotics have been administered, a large-bore (12- to 14-gauge) needle is placed into the hematocolpos under abdominal ultrasonographic visualization (Fig. 61–5). The fluid is extremely viscous, and saline irrigation may be required repeatedly to evacuate the blood (Fig. 61–6). With persistence, the clot can be broken up and the fluid eventually completely evacuated. After this, a regimen to reduce uterine bleeding is initiated, such as Depo-Provera, continuous oral contraceptives, or gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogues. Emergent decompression allows for vaginal dilation. Dilation of the lower vagina improves the chances for a direct anastomosis of the upper and lower vaginal mucosa.

Surgical resection of a transverse vaginal septum may present an unexpected challenge to an inexperienced surgeon. First, a cruciate incision is made at the vaginal opening and the connective tissue is bluntly dissected toward the hematocolpos. Occasionally, it may be difficult to locate the upper vagina. If this is a problem, abdominal ultrasonography can be performed to identify the hematocolpos (Fig. 61–7). Once the upper vagina is visualized with ultrasound, a needle is passed into the upper vagina (Fig. 61–8A). If small, the hematocolpos can be distended to enlarge the upper vagina. An incision is made along the needle tract into the upper vagina.

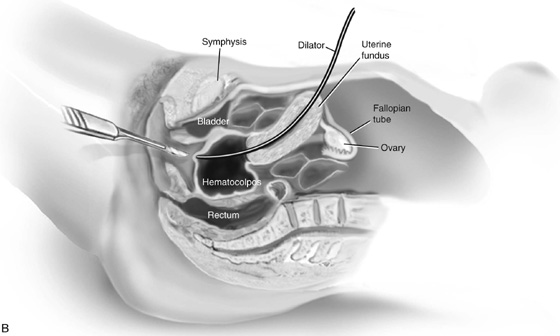

Laparotomy may be necessary if the upper vagina still cannot be visualized. A probe is placed through the uterine fundus, through the cervix, and into the upper vagina (Fig. 61–8B). With this probe used as a guide, the upper vagina can be readily identified and opened without risk of injury to the bowel or bladder.

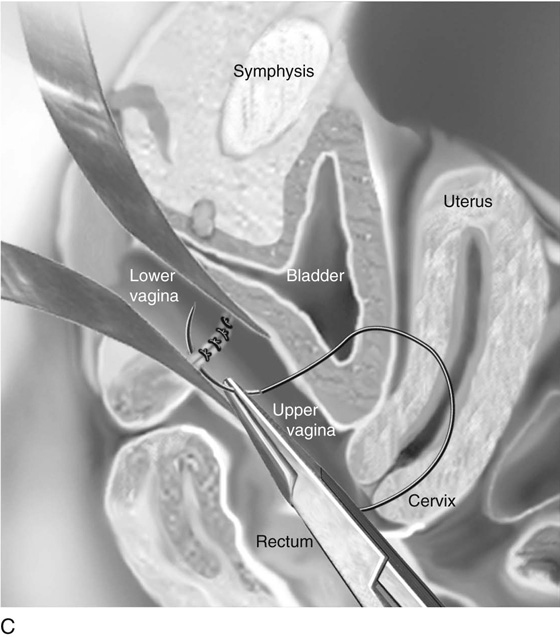

Once open, the septum is progressively dilated with cervical dilators. A transverse incision is made to increase the width of the vagina. Next, the upper and lower vaginal mucosa is reanastomosed transversely with interrupted 3-0 nonreactive absorbable sutures (Fig. 61–8C). If needed, the upper and lower vaginal mucosal edges are undermined and mobilized to bring down the tissues.

A Z-plasty repair may be beneficial if there is a wide gap between the lower and upper vagina (Fig. 61–8D). This approach allows anastomosis with minimal shortening of the vagina. The upper vagina must be identified, as discussed previously (see Figs. 61–7, 61–8). After the initial incision connects the lower and upper vagina, a balloon catheter is placed into the upper vagina to provide traction and orientation. An X-shaped incision is made at the apex of the lower vagina. The shape of the incision avoids extension of the incision into the bladder or rectum. The edges of the flaps are tagged with 3-0 nonreactive absorbable sutures. The lower vaginal flaps are mobilized by dissecting the connective tissue from the mucosa. Next, the connective tissue between the lower and upper vaginal tubes is resected laterally. The upper vaginal mucosa is mobilized and opened with an X-shaped incision. The edges of the upper vaginal flaps are tagged with suture. The Z-plasty is completed by suturing the tagged edge of the lower flaps to the base of the upper flaps, then suturing the edge of the upper flaps to the base of the lower flaps. The remaining vaginal mucosa is approximated with interrupted absorbable sutures.

When the gap between the upper and lower vagina is too large to accommodate these closures, skin grafting from the buttock may be necessary. The graft is prepared as described for the McIndoe vaginoplasty, but the length is limited to the size needed to approximate the upper and lower vaginal edges. The graft is then sutured to the upper vagina with simple interrupted sutures of 4-0 polyglycolic acid, then to the lower vagina. The redundant tissue is excised.

Alternatively, when a small gap between the upper and lower vagina cannot be approximated, a Neoprene dilator with a hollow center to allow cervical drainage may be placed in the vagina. Eventually, stratified squamous epithelium covers the denuded area.

FIGURE 61–4 Magnetic resonance image of a patient with a large transverse vaginal septum. The hematocolpos is white. The vagina communicates with the uterus, and a hematometrium is evident.

FIGURE 61–5 Hematocolpos caused by a transverse vaginal septum is seen with abdominal ultrasound (midline sagittal). Ultrasound-directed placement of a large-bore needle from the lower vagina, followed by persistent flushing and drainage, will eventually decompress the hematocolpos. This approach may increase the risk of upper genital tract infection and is appropriate only when a large transverse vaginal septum is present, and when the patient will benefit from dilation of the lower vagina before resection of the septum and anastomosis.

FIGURE 61–6 The septum has been incised, and the pent-up viscous blood and mucus drains from the vagina. The operator’s left finger has been inserted into the rectum. The guide, a 16-gauge needle, is noted just to the patient’s left (of the flowing dark blood).

FIGURE 61–7 Abdominal ultrasound (midline sagittal) is used to identify the upper vagina after the bladder is filled with saline. Here, a complex hematocolpos is identified inferior to the cervix and uterus.

FIGURE 61–8 A. A needle is passed from the lower vagina into the hematocolpos under abdominal ultrasound guidance when the upper vagina cannot be identified after dissection. B. Laparotomy is necessary when the upper vagina cannot be identified after surgical exploration or with the use of abdominal ultrasound. After the abdomen has been opened, a long cervical dilator or uterine sound is passed through the fundus into the uterine cavity and cervix. Pressure is placed against the upper vagina. The rigid dilator is identified vaginally. The upper vaginal mucosa is sharply entered. C. The upper and lower vaginal mucosal edges are approximated with interrupted 3-0 nonreactive, delayed absorbable sutures. D. A split-thickness skin graft may be used when the upper and lower vaginal edges cannot be approximated. An appropriately sized graft is harvested from the buttock and is sutured into place. A foam pad covered with a sterile condom can be placed into the vagina, as described for a McIndoe vaginoplasty, to provide maximal contact of the graft with the paravaginal connective tissue.

Longitudinal Vaginal Septum

A longitudinal vaginal septum is usually asymptomatic, although some women may complain of dyspareunia or leakage when using tampons, and a septum may tear during vaginal birth. A longitudinal vaginal septum is caused by failure of distal vaginal cannulation; it is usually accompanied by cervical duplication. Repair is not required in asymptomatic patients. However, some women may request resection of the septum to enable the use of tampons and to prevent rupture during delivery.

The septum is exposed for surgery by placing two fingers or two narrow retractors in each side of the vaginal septum and retracting posteriorly (Fig. 61–9). A Haney or Kelly clamp is placed across the septum near the anterior and posterior vaginal walls. Bladder injury is avoided by leaving a small segment of the septum on the anterior wall. If the septum is narrow, the central aspect is cut, and each wall is sutured with absorbable suture. If the septum is wide, excess tissue may be excised. The dissection continues until the upper vagina near the cervix has been divided. However, complete excision of the upper vaginal septum is often unnecessary.

Obstructed Hemivagina

An adolescent with a double uterus and cervix typically presents with severe pain caused by an obstructed hemivagina. The obstruction is caused by canalization failure and failure to absorb the vaginal septum. A high incidence of renal anomalies has been noted on the side of the obstructed hemivagina. A hematocolpos forms in the obstructed hemivagina with menarche, and each episode of bleeding from the ipsilateral hemiuterus causes additional distention and pain (Fig. 61–10). A pelvic mass is identified during pelvic and rectal examination. On speculum examination, the nonobstructed cervix may not be visible, especially if the vagina is greatly distorted from a large hematocolpos from the contralateral obstruction. Findings on vaginal ultrasonography may be confusing because the obstructed hematocolpos is found inferior to the nonobstructed cervix. The diagnosis can be made with abdominal ultrasonography and confirmed with MRI if needed.

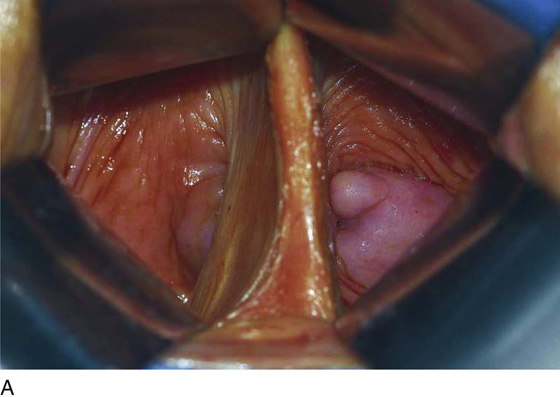

The initial incision is most important for safe resection of the obstructed hemivagina. A deep lateral incision made in the distended hemivagina should be followed by an immediate release of dark blood from the hematocolpos. Although the mass should be easily identified by palpation of the distended cystic mass and the bulge into the vagina, abdominal ultrasonography may be used to ensure that the initial incision is made into the hematocolpos. After release of the hematocolpos, the vagina is irrigated. The vaginal septum superior to the initial incision site is then resected as described for the longitudinal vaginal septum. The entire inferior margin of the vaginal septum is resected to avoid formation of a vaginal pocket. A residual pocket may trap menstrual blood and cervical secretions and cause bothersome intermenstrual bleeding or discharge.

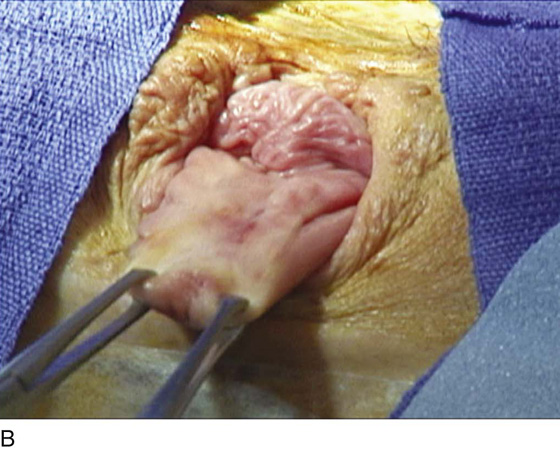

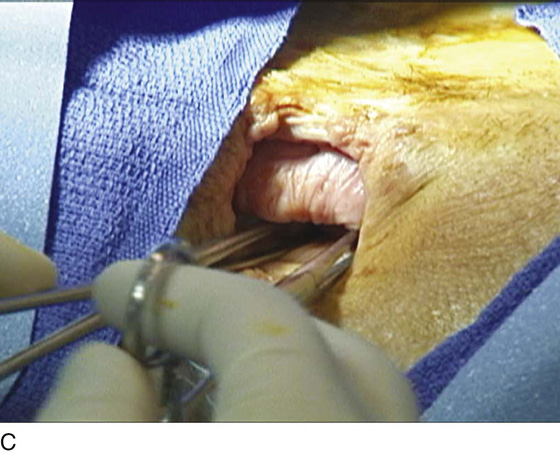

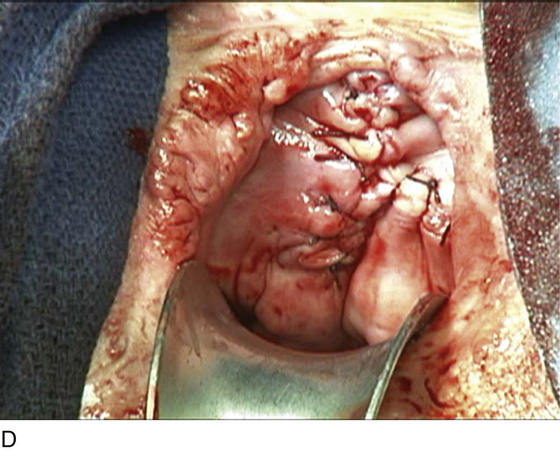

Bladder Exstrophy

A variant of the exstrophy-epispadias complex, bladder exstrophy is a rare defect that occurs in 1 : 30,000 to 1 : 50,000 live births. Bladder exstrophy is characterized by (1) absence of the lower anterior abdominal wall in the midline, (2) an absent anterior bladder wall, such that the posterior bladder wall and ureters open directly into the abdominal wall defect, (3) wide separation of the rectus muscles, (4) absence of the symphysis pubis and wide separation of the pubic rami connected by a bridge of fibrous tissues(s), (5) separation of the clitoris into two bodies and division of the pubic hair and mons, (6) a poorly defined bladder neck and a short patulous urethra, and (7) an anteriorly displaced vagina and anus with a short perineum and deficient pelvic floor musculature. These defects are thought to be due to overdevelopment of the cloacal membrane, which does not permit migration of the anterior abdominal wall mesoderm. The cloacal membrane is left unsupported and subsequently ruptures, leading to lack of lower abdominal wall development. The condition necessitates multiple reconstructive surgeries throughout childhood to preserve bladder function and continence. Numerous procedures have been used in the past to facilitate urinary diversion, with ureterosigmoidostomy probably being the most common (Fig. 61–11A). However, primary bladder closure, with or without osteotomy, later followed by bladder neck reconstruction and bilateral ureteroneocystostomy, is currently the most common sequence of urologic operations performed. A significant number of these women develop a significant pelvic organ prolapse, especially those who have experienced childbirth. Figure 61–11B through D demonstrates a posthysterectomy vault prolapse in a woman with bladder exstrophy. Previously mentioned vaginal abnormalities are seen.

FIGURE 61–9 A. Two narrow, curved retractors are placed on each side of the vaginal septum and retracted posteriorly. A curved Kelly clamp is placed across the septum on the anterior and posterior walls. B. The septum is cut, and each wall is sutured with absorbable suture. If the septum is wide, excess tissue may be excised. C. The dissection continues until the upper vagina near the cervix has been divided. However, complete excision of the upper vaginal septum is not necessary.

FIGURE 61–10 This patient had uterine didelphys with a right-sided vaginal mass, which represents an obstructed right hemivagina. She presented with vaginal and abdominal pain in the setting of regular menses (occurring from the patent left hemivagina and uterus). Preoperative evaluation revealed an absent right kidney.

FIGURE 61–11 A. Intravenous pyelogram in a patient with bladder exstrophy who underwent bilateral ureterosigmoidostomy. B. Complete posthysterectomy vault prolapse in a patient with bladder exstrophy. C. The prolapse has been reduced in the posterior direction with two Allis clamps. D. The prolapse has been surgically corrected.

Lesley L. Breech

Lesley L. Breech  Bradley S. Hurst

Bradley S. Hurst  John A. Rock

John A. Rock