CHAPTER 14 Congenital Lung Anomalies

Step 1: Surgical Anatomy

Step 2: Preoperative Considerations

Infants may present with respiratory distress, diminished breath sounds, hyperresonance over the involved thorax, and evidence of mediastinal shift.

Infants may present with respiratory distress, diminished breath sounds, hyperresonance over the involved thorax, and evidence of mediastinal shift. Chest radiographs are usually diagnostic, with hyperlucency of the involved lobe, collapse or atelectasis of the other lobes, and shift of the heart toward the opposite thorax. Fig. 14-1 is a chest radiograph demonstrating overexpanded congenital lobar emphysema of the right middle lobe and significant compression of the right upper and lower lobes.

Chest radiographs are usually diagnostic, with hyperlucency of the involved lobe, collapse or atelectasis of the other lobes, and shift of the heart toward the opposite thorax. Fig. 14-1 is a chest radiograph demonstrating overexpanded congenital lobar emphysema of the right middle lobe and significant compression of the right upper and lower lobes. CCAMs are commonly diagnosed on prenatal ultrasound. Large lesions may result in fetal nonimmune hydrops caused by compression of the mediastinum and vena cava obstruction. Spontaneous regression may occur in 40% to 80% of prenatally detected lesions.

CCAMs are commonly diagnosed on prenatal ultrasound. Large lesions may result in fetal nonimmune hydrops caused by compression of the mediastinum and vena cava obstruction. Spontaneous regression may occur in 40% to 80% of prenatally detected lesions. The most common presenting symptom is respiratory distress. Initial imaging studies include chest radiographs.

The most common presenting symptom is respiratory distress. Initial imaging studies include chest radiographs. Lesions seen on ultrasound might not be detected by plain films, and computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be helpful. Common radiologic findings include large cystic spaces in the hemithorax with mediastinal shift, or multiple cysts may be seen.

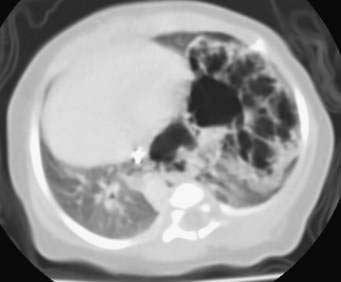

Lesions seen on ultrasound might not be detected by plain films, and computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be helpful. Common radiologic findings include large cystic spaces in the hemithorax with mediastinal shift, or multiple cysts may be seen. Figures 14-2 and 14-3 are of a neonate with a congenital cystic adenomatoid malformation of the left lower lobe. The left lung is overexpanded with multiple cystic areas present. There is significant shift of the mediastinum to the right hemithorax. The stomach bubble and nasogastric tube are situated below the diaphragm, aiding in the differential diagnosis of congenital diaphragmatic hernia.

Figures 14-2 and 14-3 are of a neonate with a congenital cystic adenomatoid malformation of the left lower lobe. The left lung is overexpanded with multiple cystic areas present. There is significant shift of the mediastinum to the right hemithorax. The stomach bubble and nasogastric tube are situated below the diaphragm, aiding in the differential diagnosis of congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Symptomatic neonates should undergo urgent surgical excision. Infants who remain asymptomatic should undergo elective resection at around 6 to 12 months of age to avoid the risks of neonatal anesthesia. All CCAMs that do not spontaneously involute in the first few months of life should be removed because of the risk of recurrent pneumonias and the potential for malignant transformation.

Symptomatic neonates should undergo urgent surgical excision. Infants who remain asymptomatic should undergo elective resection at around 6 to 12 months of age to avoid the risks of neonatal anesthesia. All CCAMs that do not spontaneously involute in the first few months of life should be removed because of the risk of recurrent pneumonias and the potential for malignant transformation. Neonates may be asymptomatic or have respiratory distress, pneumonia, feeding difficulties, or congestive heart failure resulting from arteriovenous shunting. Intralobar sequestrations are found within the surrounding normal lung tissue, most commonly in the left lower lobe. These also have a systemic arterial supply but commonly drain through the pulmonary veins. The most common presenting symptom in a neonate is respiratory distress.

Neonates may be asymptomatic or have respiratory distress, pneumonia, feeding difficulties, or congestive heart failure resulting from arteriovenous shunting. Intralobar sequestrations are found within the surrounding normal lung tissue, most commonly in the left lower lobe. These also have a systemic arterial supply but commonly drain through the pulmonary veins. The most common presenting symptom in a neonate is respiratory distress. Initial imaging studies include chest radiographs that commonly show a left-sided lower lobe mass or consolidation. Additional imaging, including CT and MRI, may be helpful for definitive diagnosis and to outline the large systemic artery arising from the subdiaphragmatic aorta (Fig. 14-4, arrow).

Initial imaging studies include chest radiographs that commonly show a left-sided lower lobe mass or consolidation. Additional imaging, including CT and MRI, may be helpful for definitive diagnosis and to outline the large systemic artery arising from the subdiaphragmatic aorta (Fig. 14-4, arrow). Neonates with respiratory distress should undergo urgent surgical resection. Older infants and children may have recurrent respiratory infections and should have an elective resection after the infection has been treated. Asymptomatic neonates whose lesions appear to have regressed on ultrasound should undergo follow-up imaging studies. Those neonates with asymptomatic pulmonary sequestration should undergo elective resection, as suggested for CCAM.

Neonates with respiratory distress should undergo urgent surgical resection. Older infants and children may have recurrent respiratory infections and should have an elective resection after the infection has been treated. Asymptomatic neonates whose lesions appear to have regressed on ultrasound should undergo follow-up imaging studies. Those neonates with asymptomatic pulmonary sequestration should undergo elective resection, as suggested for CCAM.Step 3: Operative Steps

General

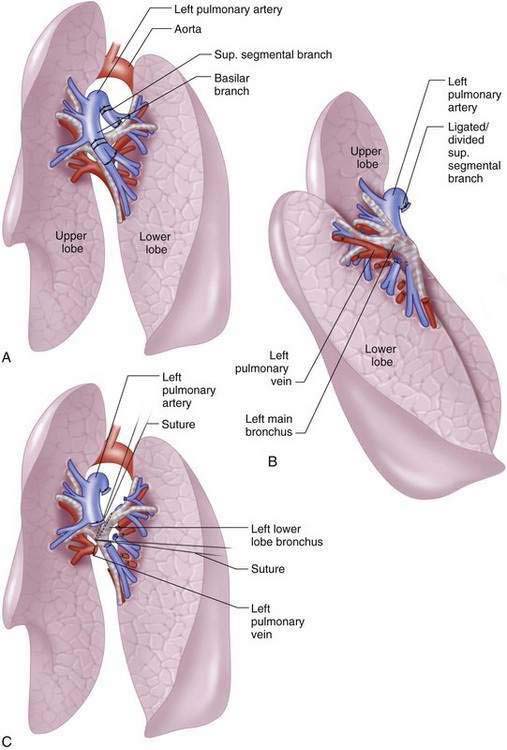

Left Lower Lobectomy

Thoracoscopic Lobectomy

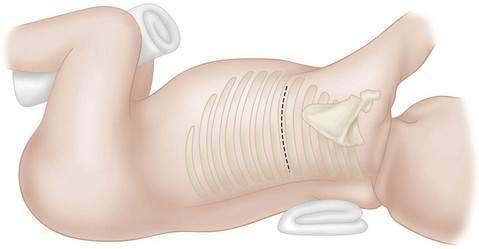

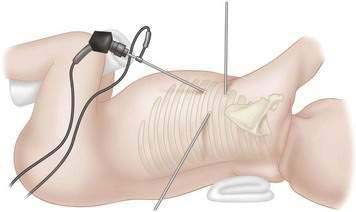

Single lung ventilation, as described previously herein, is achieved, but those infants and children who do not tolerate single lung ventilation are not candidates for this procedure. The patient is positioned laterally, and the surgeon and assistant stand on the same side, facing the patient’s abdomen. There is a single video monitor placed on the opposite side of the patient. A valved 5-mm port is placed in the midaxillary line about the fifth intercostal space. A controlled pneumothorax is created by insufflating 4 torr CO2 at 1 L/min, which allows excellent visualization of the chest without the need for manual lung retraction. Two to three additional ports are placed in a triangular fashion, and 3.5-mm instruments are used (Fig. 14-7). The techniques follow those of the open procedure, mainly division of the pulmonary fissure, dissection and ligation of the arteries, veins, and the bronchus. The pulmonary vessels and the systemic vessels of a pulmonary sequestration may be sealed and divided with the Ligasure. This instrument is useful for vessels 9 mm or smaller. It is also useful in division of the fissure. Larger vessels may require endoclips, suture ligation, or an Endo-GIA stapler. The bronchus may be handled with an Endo-GIA stapler, but the chest cavity of many infants is too small to accommodate this device. In those instances, the bronchus may be divided and sutured intracorporeally with interrupted absorbable sutures. The posterolateral port incision may be enlarged to remove the specimen, or a retrieval bag may be used. A 12 French chest tube may be placed through one of the trocar sites and placed to 10 to 15 mm H2O suction.

Single lung ventilation, as described previously herein, is achieved, but those infants and children who do not tolerate single lung ventilation are not candidates for this procedure. The patient is positioned laterally, and the surgeon and assistant stand on the same side, facing the patient’s abdomen. There is a single video monitor placed on the opposite side of the patient. A valved 5-mm port is placed in the midaxillary line about the fifth intercostal space. A controlled pneumothorax is created by insufflating 4 torr CO2 at 1 L/min, which allows excellent visualization of the chest without the need for manual lung retraction. Two to three additional ports are placed in a triangular fashion, and 3.5-mm instruments are used (Fig. 14-7). The techniques follow those of the open procedure, mainly division of the pulmonary fissure, dissection and ligation of the arteries, veins, and the bronchus. The pulmonary vessels and the systemic vessels of a pulmonary sequestration may be sealed and divided with the Ligasure. This instrument is useful for vessels 9 mm or smaller. It is also useful in division of the fissure. Larger vessels may require endoclips, suture ligation, or an Endo-GIA stapler. The bronchus may be handled with an Endo-GIA stapler, but the chest cavity of many infants is too small to accommodate this device. In those instances, the bronchus may be divided and sutured intracorporeally with interrupted absorbable sutures. The posterolateral port incision may be enlarged to remove the specimen, or a retrieval bag may be used. A 12 French chest tube may be placed through one of the trocar sites and placed to 10 to 15 mm H2O suction.Step 4: Postoperative Care

Step 5: Pearls and Pitfalls

Congenital Lobar Emphysema

Congenital Cystic Adenomatoid Malformations

Pulmonary Sequestration

Albanese CT, Rothenberg SS. Experience with 144 consecutive pediatric thoracoscopic lobectomies. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech. 2007;17:339-341.

Duncombe GJ, Dickinson JE, Kikiros CS. Prenatal diagnosis and management of congenital cystic adenomatoid malformation of the lung. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;187:950-954.

Hood M. Techniques in general thoracic surgery. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1985. pp. 101-133

Laberge JM, Puligandia P, Flageole H. Asymptomatic congenital lung lesions. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2005;14:16-33.

Mei-Zahav M, Konen O, Manson D, Langer JC. Is congenital lobar emphysema a surgical disease? J Pediatr Surg. 2006;41:1058-1061. 2006

Rothenberg SS. Experience with thoracoscopic lobectomy in infants and children. J Pediatr Surg. 2003;38:102-104.