Chapter 368 Congenital Disorders of the Nose

Physiology

The nose is responsible for olfaction and initial warming and humidification of inspired air. In the anterior nasal cavity, turbulent airflow and coarse hairs enhance the deposition of large particulate matter; the remaining nasal airways filter out particles as small as 6 µm in diameter. In the turbinate region, the airflow becomes laminar and the airstream is narrowed and directed superiorly, enhancing particle deposition, warming, and humidification. Nasal passages contribute as much as 50% of the total resistance of normal breathing. Nasal flaring, a sign of respiratory distress, reduces the resistance to inspiratory airflow through the nose and can improve ventilation (Chapter 365).

Congenital Disorders

Nasal bones can be sufficiently malformed to produce severe narrowing of the nasal passages. Often, such narrowing is associated with a high and narrow hard palate. Children with these defects can have significant obstruction to airflow during infections of the upper airways and are more susceptible to the development of chronic or recurrent hypoventilation (Chapter 17). Rarely, the alae nasi are sufficiently thin and poorly supported to result in inspiratory obstruction, or there may be congenital nasolacrimal duct obstruction with cystic extension into the nasopharynx, causing respiratory distress.

Choanal Atresia

Diagnosis

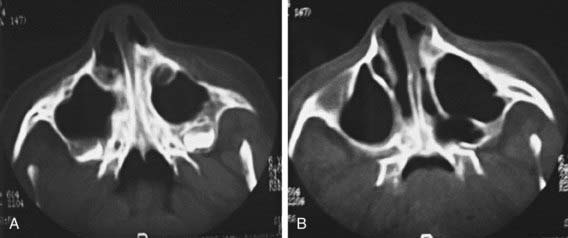

Diagnosis is established by the inability to pass a firm catheter through each nostril 3-4 cm into the nasopharynx. The atretic plate may be seen directly with fiberoptic rhinoscopy. The anatomy is best evaluated by using high-resolution CT (Fig. 368-1).

Congenital Midline Nasal Masses

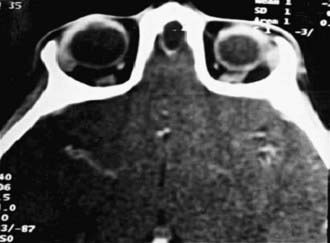

Dermoids, gliomas, and encephaloceles (in descending order of frequency) occur intranasally or extranasally and can have intracranial connections. Nasal dermoids often have a dimple or pit on the nasal dorsum, sometimes with hair being present, and can predispose to intracranial infections if an intracranial fistula or sinus is present. Recurrent infection of the dermoid itself is more common. Gliomas or heterotopic brain tissue are firm, whereas encephaloceles are soft and enlarge with crying or the Valsalva maneuver. Diagnosis is based on physical examination findings and results from imaging studies. CT provides the best bony detail, but MRI allows sagittal views, which may be needed to further define intracranial extension (Fig. 368-2). Surgical excision of these masses is generally required, with the extent and surgical approach based on the type and size of the mass.

Other nasal masses include hemangiomas, congenital nasolacrimal duct obstruction (which can occur as an intranasal mass), nasal polyps, and tumors such as rhabdomyosarcoma (Chapter 494). Nasal polyps are rarely present at birth, but the other masses often present at birth or in early infancy (Chapter 370).

Poor development of the paranasal sinuses and a narrow nasal airway are associated with recurrent or chronic upper airway infection in Down syndrome (Chapter 76).

Aramaki M, Udaka T, Kosaki R, et al. Phenotypic spectrum of CHARGE syndrome with CHD7 mutations. J Pediatr. 2006;148:410-414.

Burrow TA, Saal HM, de Alarcon A, et al. Characterization of congenital anomalies in individuals with choanal atresia. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2009;135:543-547.

Durmaz A, Tosun F, Yldrm N, et al. Transnasal endoscopic repair of choanal atresia: results of 13 cases and meta-analysis. J Craniofac Surg. 2008;19(5):1270-1274.

Giffon SD, Goncalves VM, Zanardi VA, et al. Cerebellar involvement in midline facial defects with ocular hypertelorism. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2006;43:466-470.

Harley EH. Pediatric congenital nasal masses. Ear Nose Throat J. 1991;70:28-32.

Jongmans MCJ, Admiraal RJ, vander Donk KP, et al. CHARGE syndrome: the phenotypic spectrum of mutations in the CHD7 gene. J Med Genet. 2006;43:306-314.

Khafagy YW. Endoscopic repair of bilateral congenital choanal atresia. Laryngoscope. 2002;112:316-319.

Rahbar R, Jones DT, Nuss RC, et al. The role of mitomycin in the prevention and treatment of scar formation in the pediatric aerodigestive tract: friend or foe? Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2002;128:401-406.

Rohrich RJ, Lowe JB, Schwartz MR. The role of open rhinoplasty in the management of nasal dermoid cysts. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1999;10:2163-2170.

Samadi DS, Shah UK, Handler SD, et al. Choanal atresia: a twenty-year review of medical comorbidities and surgical outcomes. Laryngoscope. 2003;113:254-258.

Van Den Abbeele T, Triglia JM, Francois M, et al. Congenital nasal pyriform aperture stenosis: diagnosis and management of 20 cases. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2001;110:70-75.

Veruloed MPJ, Hoevenadrs-van den Boom MAA, Knoors H, et al. CHARGE syndrome: relations between behavioral characteristics and medical conditions. Am J Med Genet. 2006;140A:851-862.

Zuckerman JD, Zapata S, Sobol SE. Single stage choanal atresia in the neonate. Arch Otolaryng Head Neck Surg. 2008;134:1090-1093.