Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia

After reading this chapter, you will be able to:

• List the anatomic alterations of the lungs associated with congenital diaphragmatic hernia.

• Describe the causes of congenital diaphragmatic hernia.

• List the cardiopulmonary clinical manifestations associated with congenital diaphragmatic hernia.

• Describe the general management of congenital diaphragmatic hernia.

• Describe the clinical strategies and rationales of the SOAP presented in the case study.

• Define key terms and complete self-assessment questions at the end of the chapter and on Evolve.

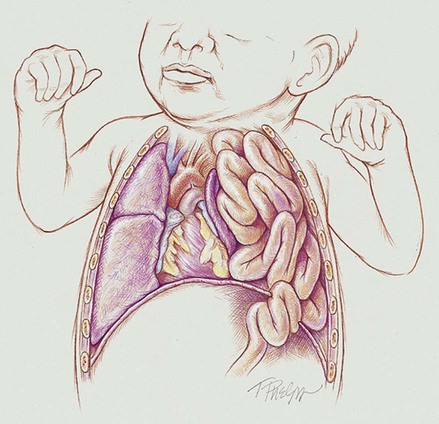

Anatomic Alterations of the Lungs

During normal fetal development, the diaphragm first appears anteriorly between the heart and liver and then progressively grows posteriorly. Between the eighth and tenth week of gestation, the diaphragm normally completely closes at the left Bochdalek foramen, which is located posteriorly and laterally on the left diaphragm. At about the tenth week of gestation (close to the same time the Bochdalek foramen is closing), the intestines and stomach normally migrate from the yolk sac. If, however, the bowels reach this area before the Bochdalek foramen closes, a hernia results—a congenital diaphragmatic hernia (CDH) (also called a Bochdalek hernia or posterior-lateral diaphragmatic hernia). In other words, a Bochdalek hernia is an abnormal hole in the posterolateral corner of the left diaphragm that allows the intestines—and in some cases the stomach—to move directly into the chest cavity and compress the developing lungs.*

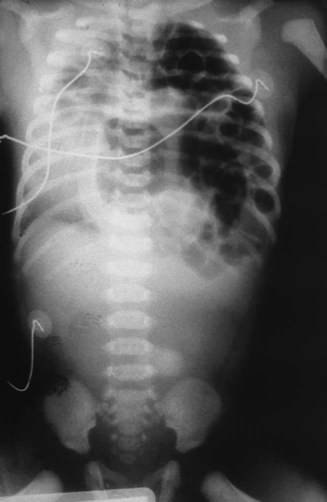

As shown in Figure 38-1, the effects of a diaphragmatic hernia are similar to the effects of a pneumothorax or hemothorax—the lungs are compressed. As the condition becomes more severe, atelectasis and complete lung collapse may occur. When this happens, the heart and mediastinum are pushed to the right side of the chest—called dextrocardia. In addition, long-term lung compression in utero causes pulmonary hypoplasia, which is most severe on the affected (ipsilateral) side but also occurs on the unaffected (contralateral) side.

Finally, as a consequence of the hypoxemia associated with a diaphragmatic hernia, these babies often develop hypoxia-induced pulmonary arterial vasoconstriction and vasospasm, which produces a state of pulmonary hypertension. As a general rule, however, these babies only have a transient state of pulmonary hypertension until the diaphragmatic hernia is repaired. This is different from persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn (PPHN) (see Chapter 31).

CASE STUDY

Diaphragmatic Hernia

Admitting History and Physical Examination

Respiratory Assessment and Plan

O Vital signs: On ECMO HR 145, BP 70/45, RR 65 (8 mechanical breaths), T 37° C (96.8° F). Skin: Pink and normal. Breath sounds: Right lung—normal; left lung—rhonchi and crackles. No chest tube bubbles. ABGs: pH 7.36, Paco2 44,  23, Pao2 73, Sao2 94%. CXR: Right lung normal; atelectasis and hypoplasia in left lower lung.

23, Pao2 73, Sao2 94%. CXR: Right lung normal; atelectasis and hypoplasia in left lower lung.

• On ECMO, ventilator-dependent, but improving (vital signs, skin color, ABGs)

• Mild amount of large and small airway secretions (crackles, rhonchi)

P Mechanical Ventilation Protocol (continue to wean per protocol—wean pressures first, then Fio2). Lung Expansion Therapy Protocol (continue PEEP or CPAP per Mechanical Ventilator Protocol). Bronchopulmonary Hygiene Therapy Protocol (continue suction and CPT prn). Oxygen Therapy Protocol (keep Spo2 at 97% or more as the Fio2 is decreased. Do not decrease Fio2 more than 10% per hour).

Discussion

This case nicely illustrates the importance of good assessment skills. Most diaphragmatic hernias are identified before the baby is born by abdominal ultrasound of the abdomen during routine prenatal care. Unfortunately, this mother had no prenatal care, and as a result, the baby’s diaphragmatic hernia was a surprise. Fortunately, the respiratory care practitioner and nurse in this case quickly and correctly identified the possibility of the diaphragmatic hernia by noting the scaphoid abdomen. Had the student intern continued to bag the baby manually, more gas would have entered the stomach and intestines, compressing and compromising the infant’s lungs even more. The Atelectasis (see Figure 9-8) caused by the enlarged intestines was objectively confirmed on the chest radiograph. The Lung Expansion Therapy Protocol was clearly justified to offset the atelectasis after the diaphragmatic hernia was repaired.

*Most CDHs are Bochdalek hernias (about 95%). Rare CDHs include Morgagni’s hernia and congenital diaphragmatic eventration of the diaphragm. A Morgagni’s hernia is characterized by herniation through the foramina of Morgagni, which are located immediately adjacent to the xyphoid process of the sternum. The majority of Morgagni’s hernias occur on the right side of the body and are asymptomatic. A congenital diaphragmatic eventration is when there is abnormal elevation of part or all of an otherwise intact diaphragm into the chest cavity. This rare form of CDH occurs when a region of the diaphragm is thinner (commonly caused by an incomplete muscularization of the diaphragm), which in turn allows the abdominal viscera to protrude upward.

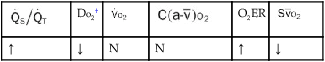

, Arterial-venous oxygen difference; DO2, total oxygen delivery; O2ER, oxygen extraction ratio;

, Arterial-venous oxygen difference; DO2, total oxygen delivery; O2ER, oxygen extraction ratio;  , pulmonary shunt fraction;

, pulmonary shunt fraction;  , mixed venous oxygen saturation;

, mixed venous oxygen saturation;  , oxygen consumption.

, oxygen consumption.

values will be lower than expected for a particular Pa

values will be lower than expected for a particular Pa 21, Pa

21, Pa 23, Pa

23, Pa 23, Pa

23, Pa