Chapter 18 Congenital Anomalies and Benign Conditions of the Vulva and Vagina

In this chapter, benign lesions of the vulva and vagina are described in the broad categories of congenital anomalies, benign neoplastic conditions, dermatologic changes, trauma, and functional disorders. Infectious conditions of the vulva and vagina are covered in Chapter 22.

Vulva

Vulva

CONGENITAL ANOMALIES OF THE VULVA

However, when the genetic sex is male (46 XY), there may be external phenotypic development along female lines. This occurs in the complete androgen insensitivity syndrome (testicular feminization), a genetic abnormality most commonly inherited as an X-linked recessive disorder. Because of a genetic deficiency of androgen receptors, the external genital development occurs along female lines. Testes are usually undescended and are located in the inguinal canals or the labial areas. After puberty, external genitalia are generally normal for females on examination, with the exception that the public hair is scanty or absent. In many cases, there is sufficient vaginal development to allow adequate coital activity. In utero, müllerian inhibiting substance is produced by the 46 XY fetus, which results in a lack of müllerian duct development and explains the absence of uterus or fallopian tubes. After puberty, the testes must be removed because malignant neoplastic transformation is possible. Ambiguous genitalia in an XY child can occur with partial androgen insensitivity (Figure 18-1).

BENIGN CONDITIONS OF THE VULVA

Significant noninfectious conditions that may affect the vulva are covered in this section. Infectious conditions are covered in Chapter 22.

Structural and Benign Neoplastic Conditions

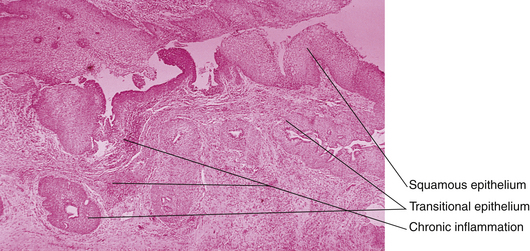

Urethral caruncles appear as small, fleshy outgrowths of the distal edge of the urethra (Figure 18-2). In children, this results from spontaneous prolapse of the urethral epithelium. On the other hand, in postmenopausal women, the caruncle occurs when the hypoestrogenic vaginal epithelium contracts and everts the urethral epithelium.

Vulvar vestibulitis (vestibular adenitis) is a relatively rare condition in which one or more of the minor vestibular glands becomes inflamed. This condition is characterized by severe introital dyspareunia and, occasionally, vulvar pain. On examination, the lesions may be visualized as 1- to 4-mm erythematous dots that are exceedingly tender when gently touched with a cotton-tipped swab. Although described as an “itis,” vestibulitis is not an infectious process and does not respond to antibiotic therapy. Topical estrogen creams or hydrocortisone may be tried, but surgical therapy to remove the glandular area may ultimately be required. Other interventions may be necessary to deal with the associated sexual dysfunction. Women with psoriasis may complain of vulvar pruritus and burning with minimal or no apparent lesions in the vulvar area. Box 18-1 lists other chronic, noninfectious vulvar conditions commonly associated with pruritus.

TRAUMATIC LESIONS

Blunt trauma to the female genitalia from falls, motor vehicle crashes, or sexual assault (see Chapter 28) most commonly results in vulvar bruising, lacerations, and hematomas. Close observation and occasionally surgical exploration may be necessary to determine the full extent of the injuries and to repair them appropriately.

Female genital mutilation (often termed female circumcision) has been performed on more than 150 million women worldwide and continues to be a common practice, especially in some African and Eastern Asian countries where the roles of women are tightly restricted. Box 18-2 contains the World Health Organization (WHO) classification of the four types of female genital mutilation, updated in 2008. The degree of anatomic change has a profound effect on infection risk, sexual function, and vaginal delivery.

BOX 18-2 World Health Organization (WHO) Classification of Female Genital Mutilation

EPITHELIAL CONDITIONS

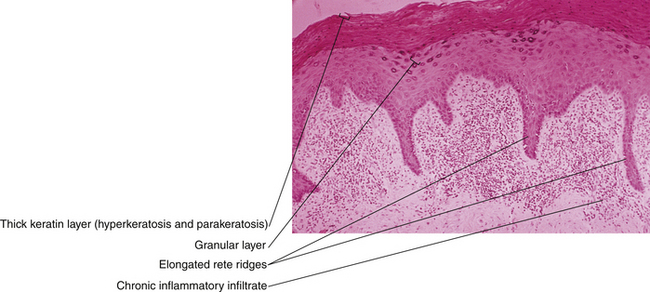

Lichen simplex chronicus (squamous cell hyperplasia) is a local thickening of the epithelium that may result from a prolonged itch-scratch cycle. Women may note pruritus and pain. Examination reveals a white or reddish, thickened, leathery, raised surface. The effects of scratching may be evident as linear excoriations. The lesions tend to be discrete but may be multiple and coexist with other vulvar pathology. Histologically, the rete ridges deepen, and there is hyperkeratosis of the superficial layer of the epidermis (Figure 18-3). Treatment includes moderate-strength steroid ointments with antipruritic agents.

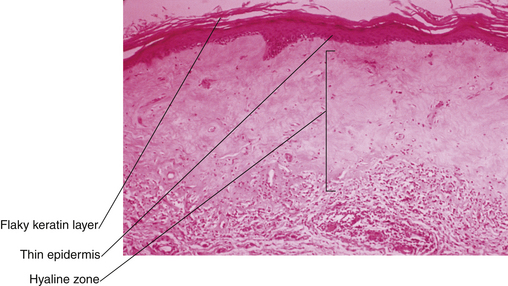

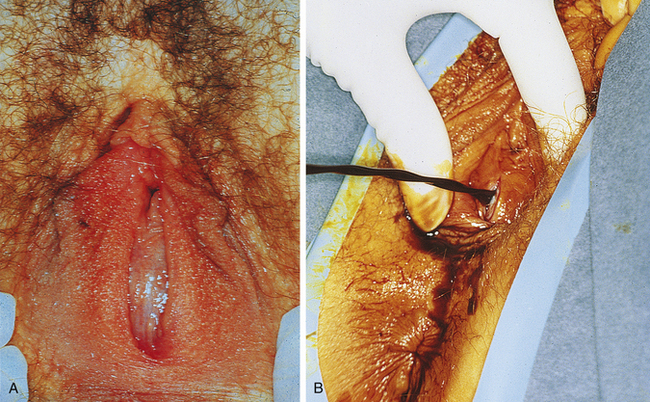

Lichen sclerosis often causes intense pruritus, dyspareunia, and burning pain. Although it can develop in any body area in any aged person, it is most frequently found on the vulva of menopausal women. On examination, the skin is thin, inelastic, and white, with a crinkled, tissue paper appearance. Ultimately, lichen sclerosis can involve all the genital area from the mons to the anal area in a keyhole pattern. Biopsy reveals a thin epithelium with loss of rete ridges and inflammatory cells lining the basement membrane (Figure 18-4). Diagnosis is important because this is a chronic, progressive disease with the potential to constrict and destroy the normal genital architecture. When untreated, there is the possibility of progression to vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN), differential type. In the long term, the labia minora are lost, the labia majora flatten, the introitus becomes severely constricted, and the clitoris becomes inverted and trapped (Figure 18-5). Combinations of lichen sclerosis and dysplasia, hyperplasia, or carcinoma are possible. Multiple biopsies may be necessary to characterize completely all the pathologies present in one woman. Treatment of lichen sclerosis involves the use of potent topical steroids such as 0.05% clobetasol. Eighty percent of lesions respond. Long-term therapy with lower-potency steroids or topical emollients may be necessary.

The epithelium of the vulva is susceptible to dermatologic disorders found elsewhere on the body surface, although the clinical manifestations of those disorders may be slightly different because of the vulva’s moist environment. A correct diagnosis is critical, and tissue punch biopsy may be required (Figure 18-6). Psoriasis generally appears velvety but may lack the characteristic scaly patches found on the flexor surfaces (e.g., knees and elbows). Eczema has a more erythematous presentation and may be difficult to diagnose unless lesions that are more characteristic can be found on the scalp, umbilicus, or extremities. Even in these circumstances, diagnostic biopsy may be needed to rule out conditions that are more serious. Pemphigus is an autoimmune blistering disease involving the vulvovaginal and conjunctival areas. Behçet’s syndrome classically involves ulcerations in the genital and oral areas, as well as superficial ocular lesions. The genital lesions are distinctive and can result over time in a scarred, fenestrated vulva. The etiology is unknown, as is an effective treatment. Diagnosis is based on the concurrence of vulvar, oral, and ocular involvement, the recurrent nature of the disease, and the exclusion of other conditions, such as syphilis and Crohn disease.

Acanthosis nigricans is most commonly found in the intertriginous area, in the axilla or on the nape of the neck (see Chapter 32, Figure 32-4). It is recognizable by its darkly pigmented velvety or warty surface. Acanthosis nigricans is related most closely to insulin resistance but can be linked less commonly to other benign conditions and malignancy.

Vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia, Paget’s disease of the vulva, and invasive tumors of the vulva are discussed in Chapter 40.

Vagina

Vagina

CONGENITAL ABNORMALITIES

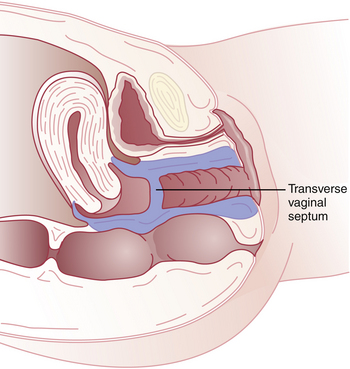

Imperforate hymen represents the mildest form of these canalization abnormalities. It occurs at the site where the vaginal plate contacts the urogenital sinus. After birth, a bulging, membrane-like structure may be noticed in the vestibule, usually blocking egress of mucus. If not detected until after menarche, an imperforate hymen may be seen as a thin, dark bluish or thicker, clear membrane blocking menstrual flow at the introitus (Figure 18-7). A similar anomaly, the transverse vaginal septum, is most commonly found at the junction of the upper and middle thirds of the vagina (Figure 18-8). At times, a transverse vaginal septum will have a sinus tract or small perforation that allows menstruation. Thus, the septum may become apparent only after intercourse is impeded. Patients with an imperforate hymen or transverse vaginal septum usually have normal development of the upper reproductive tract.

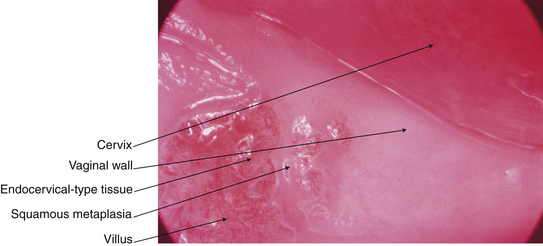

Adenosis of the vaginal wall consists of islands of columnar epithelium in the normal squamous epithelium. It is often located in the upper third of the vagina. The incidence of this finding is much higher in women exposed in utero to diethylstilbestrol (Figure 18-9).

BENIGN CONDITIONS OF THE VAGINA

Structural and Benign Neoplastic Conditions

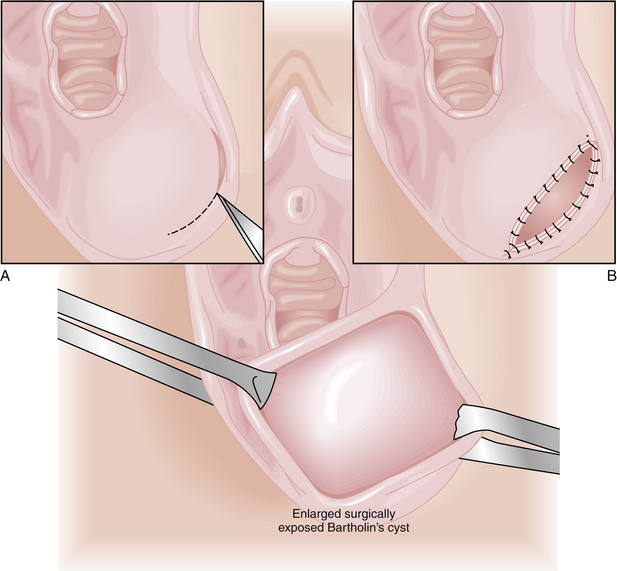

Bartholin’s cyst is the most common vulvovaginal tumor. It presents as a swelling posterolaterally in the introitus, usually unilaterally. The cyst is usually less than 3 cm in diameter and is frequently asymptomatic. Careful examination of the base of the cyst is necessary (especially in a woman older than 40 years) to rule out an underlying Bartholin’s carcinoma (see Chapter 40). Infection of the gland may result from blockage and accumulation of purulent material. When infected, a large, painful inflammatory mass can develop, and an inflatable bulb-tipped tube (Word catheter) can be inserted through a small stab incision into the mass and left in place for 4 to 6 weeks. This allows for an epithelialized tract to form that will remain open for drainage. When Bartholin’s cysts are large, symptomatic, and not infected, a marsupialization procedure can be performed (Figure 18-10).

FIGURE 18-10 Marsupialization of a Bartholin’s cyst performed to prevent reaccumulation of cyst fluid.

Structural changes that develop over time generally result from the loss of pelvic support. Cystoceles, now referred to as anterior vaginal prolapse, rectoceles or posterior vaginal prolapse, and enteroceles are more thoroughly discussed in Chapter 23. Ureterovaginal, vesicovaginal, and rectovaginal fistulas may result from infection, complications of surgery or radiation therapy, obstetric injury, or invasive cancer. They cause chronic vaginal discharge and considerable vulvovaginal irritation.

FUNCTIONAL

Vaginismus is an involuntary contraction of the vaginal introital and levator ani muscles. Vaginismus may preclude, or render very painful, vaginal penetration during coitus, pelvic examination, or tampon use. Often a history of sexual abuse or phobias about vaginal trauma is associated with vaginismus; these misconceptions and phobias may respond to education and desensitization (see Chapter 27).

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) Diagnosis and management of vulvar skin disorders ACOG Practice Bulletin, No. 93, May 2008. Obstet Gynecol, 111; 2008:1243-1253.

Bikoo M. Female genital mutilation: Classification and management. Nurs Stand. 2007;22:43-49.

Guntner J. Vulvodynia: New thoughts on a devastating condition. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2007;62:812-819.

Kaufman R.H., Faro S., Brown D., editors. Benign Diseases of the Vulva and Vagina, 5th ed, Philadelphia: Elsevier Mosby, 2005.

Kondi-Pafiti A., Graspa D., Papakonstantinou K., et al. Vaginal cysts: A common pathologic entity revisited. Clin Exp Obstet Gynecol. 2008;3591:41-44.

Zamirska A., Reich A., Berny-Moreno J., et al. Vulvar pruritus and burning sensation in women with psoriasis. Acta Derm Venereol. 2008;88:132-135.