Chapter 19 Congenital Anomalies and Benign Conditions of the Uterine Corpus and Cervix

Congenital Anomalies of the Uterine Corpus and Cervix

Congenital Anomalies of the Uterine Corpus and Cervix

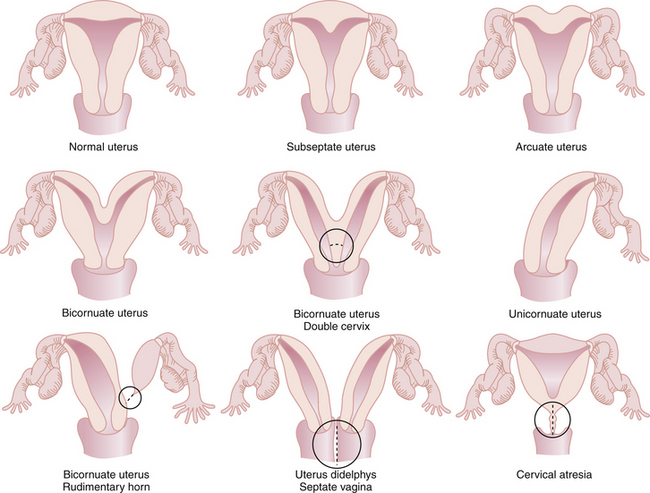

The most common anomalies of the uterus result from either incomplete fusion of the paramesonephric ducts, incomplete dissolution of the midline fusion of those ducts, or formation failures. Figure 19-1 shows variations of uterine and cervical development and demonstrates that communication between the dual systems can exist at several levels. Failure of fusion is most evident in uterus didelphys, which presents with two separate uterine bodies, each with its own cervix and attached fallopian tube and vagina. A bicornuate uterus with a rudimentary horn also represents a fusion failure. Less complete fusion failure is seen in the bicornuate uterus with or without double cervices. Incomplete dissolution of the midline fusion of the paramesonephrica explains the septate uterus. Failure of formation can be seen in the unicornuate uterus. In müllerian agenesis, there is complete lack of development of the paramesonephric system. The affected woman generally has incomplete development of the fallopian tubes associated with the absence of the uterus and most of the vagina. All these conditions occur in normal karyotypic and phenotypic females but can be associated with important anomalies of the urinary system such as a horseshoe or pelvic kidney.

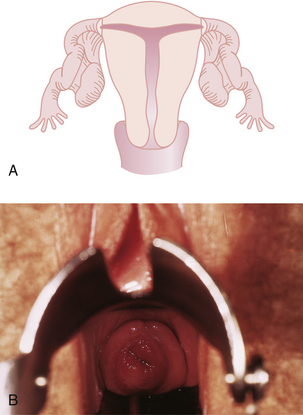

Although all these anomalies can occur spontaneously, they may also be caused by early maternal exposure to certain drugs. The most notable of these drugs is diethylstilbestrol (DES). A DES-exposed female infant has an increased risk for a small, T-shaped endometrial cavity (Figure 19-2A) or cervical collar deformity (Figure 19-2B). DES exposure in utero can also produce fallopian tube abnormalities, although it does not appear to cause abnormalities of the urinary tract.

Benign Neoplastic Conditions

Benign Neoplastic Conditions

UTERINE LEIOMYOMAS

Characteristics of Leiomyomas

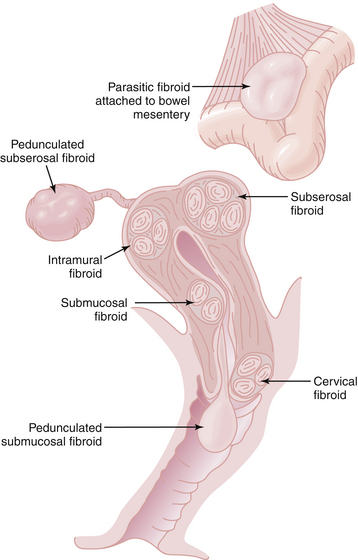

Leiomyomas always arise within the myometrium (intramural), but some migrate toward the serosal surface (subserosal) or toward the endometrium (submucosal), as depicted in Figure 19-3. Individual tumors may migrate further when they develop large pedicles. The submucosal leiomyomas can extend through the endometrial canal and abort from the cervical os. An aborting leiomyoma causes significant bleeding and cramping pain. A subserosal leiomyoma on a long pedicle can present as a mass that feels separate from the uterus. Rarely, pedunculated subserosal myomas attach to the blood supply of the omentum or bowel mesentery and lose their uterine connections to become parasitic leiomyomas. Leiomyomas can also arise in the cervix, between the leaves of the broad ligament (intraligamentous), and in the various supporting ligaments (round or uterosacral) of the uterus. Leiomyomas can invade and fill the vena cava retrograde up to the level of the atrium (intravenous leiomyomatosis).

Signs of Leiomyomas

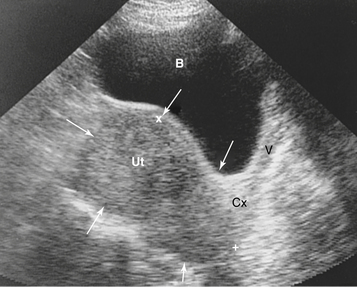

Very large fibroids can be palpated abdominally. Those smaller than 12- to 14-week gestational size are usually confined to the pelvis. The bladder should be emptied before examination to avoid confusion with urinary retention. Although submucous fibroids may not be palpable, on bimanual pelvic examination, a firm, irregularly enlarged uterus with smoothly rounded or bosselated protrusions may be felt if the tumors are subserosal or intramural. The tumors are usually nontender. Their consistency may vary from rock hard, as in the case of a calcified postmenopausal leiomyoma, to soft or even cystic, as in the case of cystic degeneration of the tumor. In general, the myomatous masses are in the midline, but sometimes a large portion of the tumor lies in the lateral aspect of the pelvis and may be indistinguishable from an adnexal mass. If the mass moves with the cervix, it is suggestive of a leiomyoma. Often the presence of a leiomyoma precludes a proper evaluation of the adnexa, but ultrasound imaging (Figure 19-4) can help to distinguish adnexal masses from laterally placed myomas.

Differential Diagnosis for Leiomyomas

The differential diagnosis of a leiomyoma is extensive and includes other uterine pathology, such as uterine sarcoma, and other processes, such as inflammation, that can cause pelvic masses. The most common differential diagnoses are an ovarian neoplasm, a tubo-ovarian inflammatory mass, a pelvic kidney, a diverticular or inflammatory bowel mass, or cancer of the colon. Ultrasonography may visualize the fibroids and identify normal ovaries apart from the leiomyomas. Adenomyosis usually results in a uniformly enlarged uterus (see Chapter 25, Figure 25-5) but may on occasion be diagnosed as a leiomyoma. Figure 19-5 shows the gross appearance of an irregularly enlarged uterus with multiple fibroids.

Surgical Management Options

Hysterectomy provides definitive therapy. About 200,000 hysterectomies are done annually in the United States to treat fibroids. If the uterus is large or bulky, laparotomy is generally the preferred approach. Vaginal hysterectomy and total laparoscopic hysterectomy are both excellent options for women with smaller myometrial uteri. If a woman desires a supracervical hysterectomy, the vaginal approach is not possible. Usually ovarian preservation is encouraged unless the woman is older than 60 years or has risk factors for ovarian carcinoma. Table 19-1 summarizes the more common nonmedical options for patients with leiomyomas.

TABLE 19-1 INTERVENTION FOR PATIENTS WITH LEIOMYOMAS NOT AMENABLE TO MEDICAL THERAPY∗

| Clinical Presentation | Nonmedical Options | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Desired fertility | Myomectomy or uterine artery embolization (UAE)† | Usually used for a limited number of leiomyomas |

| Desired uterine preservation or poor surgical risk | Endometrial ablation or UAE | UAE only for a limited number of leiomyomas |

| No desired fertility or uterine preservation | Endometrial ablation or hysterectomy | Hysterectomy is definitive therapy |

| Rapidly growing uterus (double in size in 6 months) | Exploratory laparotomy, abdominal hysterectomy | More extensive surgery if malignancy discovered |

∗ Generally, failed medical therapy or large (>12-14 weeks’ gestational size) uterus.

ENDOMETRIAL POLYPS

Endometrial polyps form from the endometrium to create abnormal protrusions of friable tissue into the endometrial cavity. They can cause menorrhagia and spontaneous bleeding during the reproductive years and postmenopausal bleeding after menopause. On ultrasound, endometrial polyps may appear as a focal thickening of the endometrial stripe. They can be more clearly recognized on saline infusion sonography or visualized directly by hysteroscopy (see Chapter 34, Figure 34-1). Endometrial polyps may evade detection by endometrial aspiration or dilation and curettage (D&C) because they are too large to be aspirated through the sampling orifice and are very flexible and can fold out of the path of the sharp curette. Histologic evaluation of the polyp is imperative because although most are benign, endometrial hyperplasia, endometrial carcinoma, and carcinosarcomas may also present as polyps.

NORMAL CERVIX

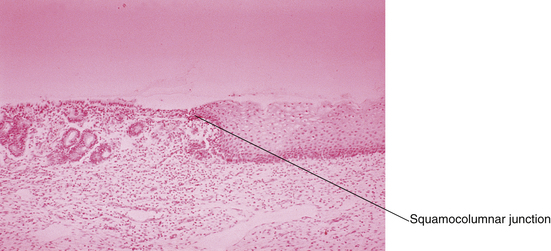

At birth, a pale pink squamous epithelium covers the outer rim of the cervix. The inner region of the ectocervix is covered with the taller columnar cells. The junction between the two is called the original squamocolumnar junction (Figure 19-6). The columnar epithelium appears redder because of the closer proximity of its underlying blood vessels to the surface. With acidification of the vagina at menarche, the ectocervix undergoes an accelerated rate of squamous metaplasia in a radial pattern, from the squamocolumnar junction inward, which produces the transformation zone. A new squamocolumnar junction is formed that moves progressively up the endocervical canal (see Chapter 38, Figure 38-1). Younger women are often found to have a reddish ring of tissue surrounding the os, which is sometimes called a cervical ectropion, but in reality, this is an area of columnar epithelium that has not yet undergone squamous metaplasia.

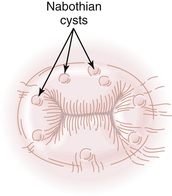

Nabothian cysts on the cervix are so common that they are considered a normal variant. They result from the process of squamous metaplasia. A layer of superficial squamous epithelium entraps an invagination of columnar cells beneath its surface. The underlying columnar cells continue to secrete mucus, and a mucous retention cyst is created. Nabothian cysts are opaque, with a yellowish or bluish hue. They vary generally in size from 0.3 to 3 cm (Figure 19-7), although larger nabothian cysts have been reported.

Epithelial Conditions of the Uterine Corpus and Cervix

Epithelial Conditions of the Uterine Corpus and Cervix

ENDOMETRIAL HYPERPLASIA

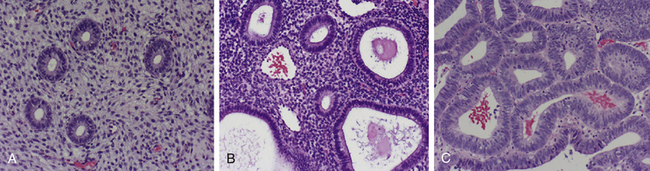

A spectrum of histologic variations exists. There are two categories (simple hyperplasia and complex hyperplasia) and two subcategories (with and without atypia). Complex atypical hyperplasia has the greatest malignant potential; about 20% to 30% of cases progress to endometrial carcinoma, if untreated. Figure 19-8 shows photomicrographs of normal proliferative endometrium, simple hyperplasia (without atypia), and complex hyperplasia (with atypia).

Functional Conditions of the Uterine Corpus and Cervix

Functional Conditions of the Uterine Corpus and Cervix

Cervical incompetence is a condition in which the cervix is unable to maintain closure under the pressure of a progressively enlarging pregnant uterus and painlessly dilates, resulting in pregnancy loss, most commonly in the second trimester (see Chapter 12). Cervical incompetence may be intrinsic (caused by poor ground substance in the cervix), the result of cervical surgery (especially loop electrosurgical excision procedure and cold-knife conization) for cervical dysplasia, or the result of DES exposure in utero.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG). Surgical alternative to hysterectomy in the management of leiomyomas. Practice Bulletin No.16. Washington, DC: ACOG; May 2000.

Cheng M.H., Wang P.H. Uterine myoma: A condition amenable to medical therapy. Emerg Drugs. 2008;13:119-133.

Espindola D., Kennedy K.A., Fischer E.G. Management of abnormal uterine bleeding and the pathology of endometrial hyperplasia. Obstet Gynecol Clin N Am. 2007;34:717-737.

Marshburn P.B., Matthews M.L., Hurst B.S. Uterine artery embolization as a treatment option for uterine myomas. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2006;33:125-144.

Viswanathan M., Hartman K., McDoy N., et al. Management of uterine fibroids: An update of the evidence. Evid Rep Technol Assess. 2007;154:1-122.

Trauma of the Uterine Corpus and Cervix

Trauma of the Uterine Corpus and Cervix