Chapter 20 Congenital Anomalies and Benign Conditions of the Ovaries and Fallopian Tubes

Benign Conditions of the Ovaries

Benign Conditions of the Ovaries

FUNCTIONAL AND BENIGN OVARIAN TUMORS

The human ovary has a striking propensity to develop a wide variety of tumors, most of which are benign. As indicated in Table 20-1, ovarian masses may be functional, inflammatory, metaplastic, or neoplastic. During the childbearing years, 70% of noninflammatory benign ovarian tumors are functional. The remainder are either neoplasms (20%) or endometriomas (10%). The management of ovarian tumors, whether functional, benign, or malignant, involves difficult decisions that may affect a woman’s hormonal status or her future fertility. Although only functional cysts and benign ovarian neoplasms are considered in detail in this chapter, diagnostic methods to differentiate benign masses from malignant ones are discussed.

| Pathogenesis | Specific Type |

|---|---|

| Functional | Follicular cysts |

| Lutein cysts | |

| Polycystic ovaries | |

| Inflammatory | Salpingo-oophoritis |

| Pyogenic oophoritis—puerperal, abortal, or related to an intrauterine device | |

| Granulomatous oophoritis | |

| Metaplastic | Endometriomas |

| Neoplastic | Premenarchal years—10% are malignant |

| Menstruating years—15% are malignant | |

| Postmenopausal years—50% are malignant |

Functional Ovarian Cysts and Tumors

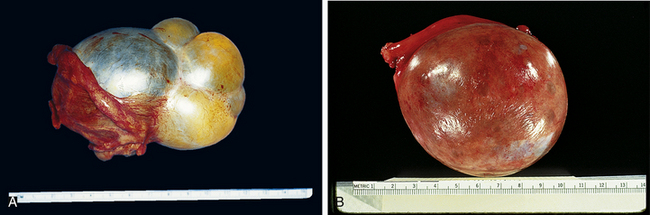

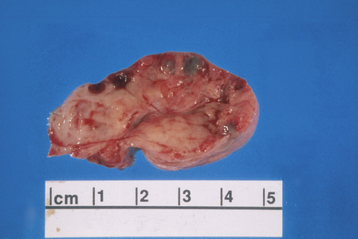

A luteoma of pregnancy is a related condition in which there is a hyperplasic reaction of ovarian theca cells, presumably from prolonged hCG stimulation during pregnancy. The luteomas characteristically appear as brown to reddish-brown nodules that may be cystic or solid. A luteoma of pregnancy (Figure 20-1) may be associated with multifetal pregnancies or hydramnios. They can cause maternal virilization in 30% of women and, less often, ambiguous genitalia in a female fetus. Although ovarian enlargement may be impressive, surgical resection is not indicated because luteomas regress spontaneously postpartum.

FIGURE 20-1 Gross appearance of a luteoma of pregnancy. Note the multiple brown nodules.

(From Voet RL: Color Atlas of Obstetric and Gynecologic Pathology. St. Louis, Mosby, 1997.)

Polycystic ovary syndrome, a functional disorder generally associated with chronic anovulation and hyperandrogenism, can also produce enlarged ovaries with multiple simple follicles (Figure 20-2). The hormonal aspects of this syndrome are discussed further in Chapter 32.

FIGURE 20-2 Ovary with multiple cysts lining the capsule consistent with polycystic ovary syndrome.

(Courtesy of Dr. Sathima Natarajan, Ronald Reagan–UCLA Medical Center.)

DIAGNOSIS

All suspicious adnexal masses in premenopausal and postmenopausal women must be carefully evaluated. Table 20-2 contains a useful risk assessment tool, the risk for malignancy index (RMI), which can be used to help identify those ovarian masses that could be malignant. The RMI has high sensitivity (87%) and specificity (97%).

TABLE 20-2 CALCULATION OF THE RISK OF MALIGNANCY INDEX∗ FOR AN OVARIAN MASS

| Criteria | Scoring System |

|---|---|

| A. MENOPAUSAL STATUS | |

| Premenopausal | 1 |

| Postmenopausal | 3 |

| B. ULTRASONIC FEATURES | |

∗ Risk of Malignancy Index = A × B × C. A cut-off value of 200 discriminates a benign from a malignant mass with a sensitivity of 87% and a specificity of 97%.

Data from Jacobs I, Oram D, Fairbanks J, et al: A risk of malignancy index incorporating CA 125, ultrasound and menopausal status for the accurate preoperative diagnosis of ovarian cancer. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 97:922, 1990.

When a patient has delayed menses, abnormal uterine bleeding, or severe pelvic pain, the differential diagnosis must include ectopic pregnancy, pelvic abscess, or adnexal torsion of a neoplastic cyst. A pregnancy test (hCG), diagnostic laparoscopy, or rarely, laparotomy may be needed. Table 20-3 lists the current modalities that are available to evaluate adnexal masses along with the sensitivity and specificity as calculated by the U.S. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. None of these modalities is accurate enough to be used alone for diagnosis.

TABLE 20-3 MODALITIES FOR THE EVALUATION OF ADNEXAL MASSES

| Modality | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Gray-scale transvaginal ultrasonography | 0.82-0.91 | 0.68-0.81 |

| Doppler ultrasonography | 0.86 | 0.91 |

| Computed tomography | 0.90 | 0.75 |

| Magnetic resonance imaging | 0.91 | 0.88 |

| Positron emission tomography | 0.67 | 0.79 |

| CA-125 level measurement | 0.78 | 0.78 |

Data from Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ): Management of adnexal mass. AHRQ Publication No. 06-E004. Rockville, MD, AHRQ, 2006.

Benign Neoplastic Ovarian Tumors

EPITHELIAL OVARIAN NEOPLASMS

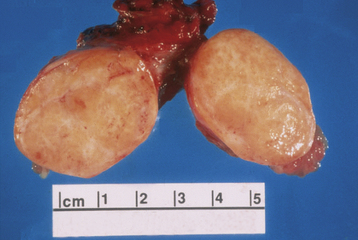

These tumors are believed to be derived from the mesothelial cells lining the peritoneal cavity and also lining the surface of the ovary. The mucinous ovarian neoplasm cytologically resembles the endocervical epithelium, the endometrioid neoplasm resembles the endometrium, and serous tumors resemble the lining of the fallopian tubes. The most common epithelial ovarian tumors are serous cystadenomas. Figure 20-3 shows the gross appearance of a mucinous and serous cystadenoma.

The Brenner tumor is a small, smooth solid ovarian neoplasm, usually benign, with a large fibrotic component that encases epithelioid cells that resemble transitional cells of the bladder (Figure 20-4). In about 33% of cases, Brenner tumors are associated with mucinous epithelial elements.

SEX CORD–STROMAL OVARIAN NEOPLASMS

The granulosa-theca cell neoplasms, as well as their androgenic counterparts, are generally referred to as functioning (not functional) ovarian tumors. They occur in any age group, from birth on, but more commonly in the postmenopausal years. Their functioning characteristics are responsible for a variety of associated presenting signs and symptoms. The granulosa-theca cell tumors promote feminizing signs and symptoms, such as precocious menarche, precocious thelarche, or premenarchal uterine bleeding during infancy and childhood. In the reproductive years, menorrhagia (with alternating amenorrhea), endometrial hyperplasia, and not infrequently, endometrial cancer, breast tenderness, and fluid retention occur. Postmenopausal bleeding may occur in older women with granulosa-theca cell tumors. In contrast, the less frequent Sertoli-Leydig cell tumors are responsible for virilizing effects, such as hirsutism, temporal baldness, deepening of the voice, clitoromegaly, and a defeminizing change in body habitus to a muscular build. Fifteen percent of these tumors produce no obvious endocrinologic effects. Except for the pure thecoma, all these tumors have low malignant potential and are discussed further in Chapter 39.

The ovarian fibroma, another ovarian stromal tumor, forms a solid, encapsulated, smooth-surfaced tumor made up of interlacing bundles of fibrocytes. It is not hormonally active. It is glistening white on its cut surface (Figure 20-5), as opposed to the soft yellow appearance of the granulosa-theca cell or the smaller hilus cell tumor. On occasion, this tumor is associated with ascites caused by the transudation of fluid from the ovarian fibroid. The flow of this ascitic fluid through the transdiaphragmatic lymphatics into the right pleural cavity may result in Meigs’ syndrome (ascites and hydrothorax in association with an ovarian fibroma). The ovarian fibroma may be associated with theca cell elements called a fibrothecoma.

GERM CELL TUMORS

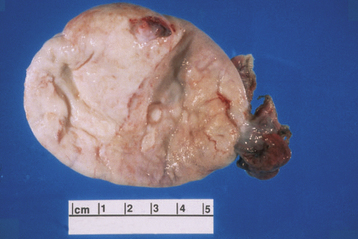

The most common ovarian neoplasm is the benign cystic teratoma, a germ cell tumor that can take on a great variety of forms, with virtually all adult tissues being represented within the mass. Ten percent to 15% of teratomas are bilateral. The benign cystic teratoma, commonly referred to as a dermoid cyst, is composed primarily of ectodermal tissue (such as sweat and sebaceous glands, hair follicles, and teeth), with some mesodermal and rarely endodermal elements. These are slow-growing tumors. Half are diagnosed in women between 25 and 50 years of age. Most are less than 10 cm in diameter. Because of the oily secretion of the sebaceous glands, the desquamated squamous cells, the presence of hair, and the presence of a dermoid tubercle (of Rokitansky), which often contains a hard, well-formed tooth, the dermoid cyst has a characteristic gross and histologic appearance (Figure 20-6). Other tissue components commonly found in benign cystic teratomas include mature brain, bronchus, thyroid, cartilage, intestine, bone, and carcinoid cells. As opposed to similar tissues found in a malignant immature teratoma, the tissues making up the benign (mature) teratoma are all of an adult, well-differentiated form.

DIAGNOSIS OF BENIGN OVARIAN TUMORS

Tumor markers, such as serum CA 125, as part of the RMI (see Table 20-2) may help to distinguish between benign and malignant masses, particularly in a postmenopausal patient. When clinical evaluation, pelvic ultrasonography, and tumor markers all indicate malignancy, the positive predictive value of the combination is high in postmenopausal women. Such patients should be referred to a gynecologic oncologist for surgical evaluation.

Benign Conditions of the Fallopian Tubes

Benign Conditions of the Fallopian Tubes

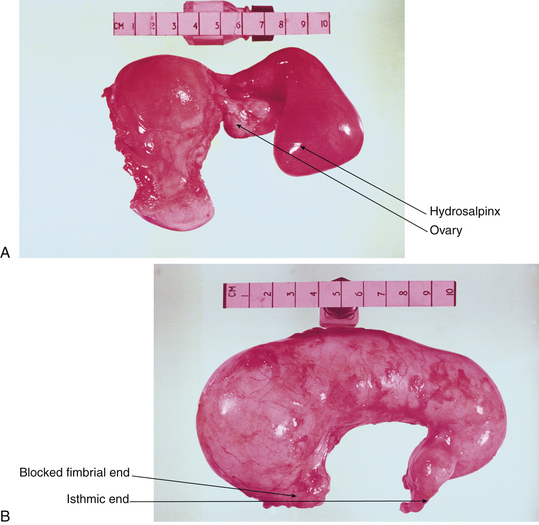

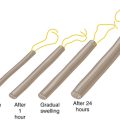

Most benign “tumors” of the fallopian tubes are infectious or inflammatory (e.g., hydrosalpinx and pyosalpinx [Figure 20-7]). Benign neoplasms of the oviducts are rare. Although the tubes, uterine corpus, and uterine cervix are from the same müllerian anlage (primordial tissue), the tubes have less of a tendency toward neoplastic transformation.

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). Management of adnexal mass. Evidence Based Report/Technology Assessment No. 130. AHRQ Publication No. 06-E004. Rockville, MD: AHRQ; 2006.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) ACOG Practice Bulletin, Number 83, July 2007. Management of adnexal masses, 2007. In Compendium of Selected Publications (ACOG). Washington, DC; pp 1372–1383.

Boyle K.J., Torrealday S. Benign gynecologic conditions. Surg Clin North Am. 2008;88:245-264.

Grimes D.A., Jones L.B., Lopez L.M., Schulz K.F. Oral contraceptives for functional ovarian cysts. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006. CD006134

Trimbos B., Hacker N.F. The case against aspirating ovarian cysts. Cancer. 1993;72:828.

Congenital Anomalies of the Ovaries and Fallopian Tubes

Congenital Anomalies of the Ovaries and Fallopian Tubes