18 Congenital and genetic disorders

Congenital abnormalities

Congenital abnormalities range from trivial morphological abnormalities, such as a rudimentary extra digit, to lethal conditions such as major brain malformations. At birth, 2–3% of infants are recognized to have a congenital malformation. By age 5, this rises to 4–6%, as abnormalities not initially evident become manifest. In 40–60%, the cause is unknown. A chromosomal/genetic cause is found in 10–15%. Environmental factors, such as congenital infections (see Chapter 17, p. 256), maternal disease (e.g. diabetes), nutritional deficiencies, hypoxia, drug and alcohol exposure contribute about 10%. The remainder arise from a combination of genetic and environmental factors.

Congenital abnormalities may be categorized as:

• Malformations – something occurs to disturb the normal development of an organ or structure. It may result in complete or partial absence, as occurs in most cases of congenital hypothyroidism, or alteration of structure, as occurs in congenital heart disease

• Disruptions – a disruption arises when the normal structure is affected by a process (usually destructive) after formation of the organ. For example, intestinal atresias are believed to result from a transient vascular insult during fetal life

• Deformations – the fetus is in a confined space. To develop normally, the fetus needs to move. Conditions which impair movement may lead to multiple postural deformities (arthrogryposis multiplex), as may occur in infants born to mothers with myasthenia gravis. Other ‘packaging defects’ are less severe, such as talipes (see Chapter 6, p. 44)

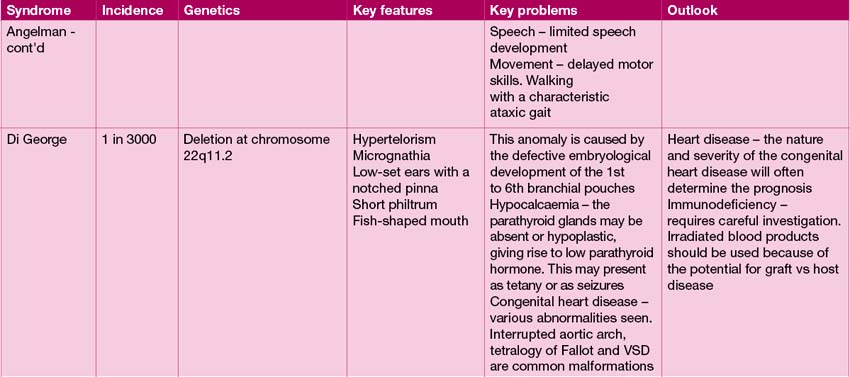

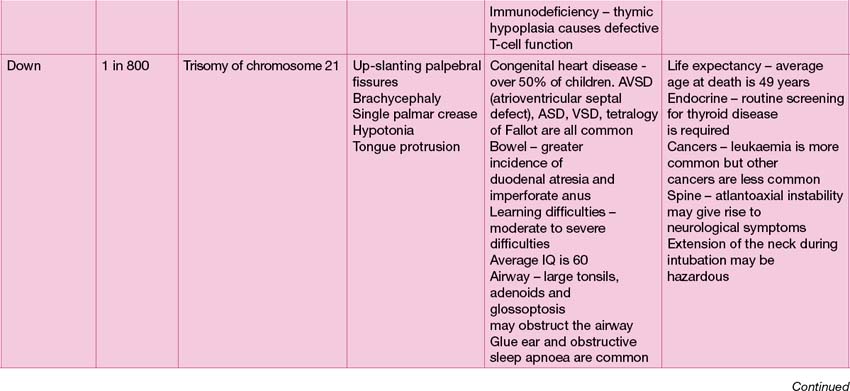

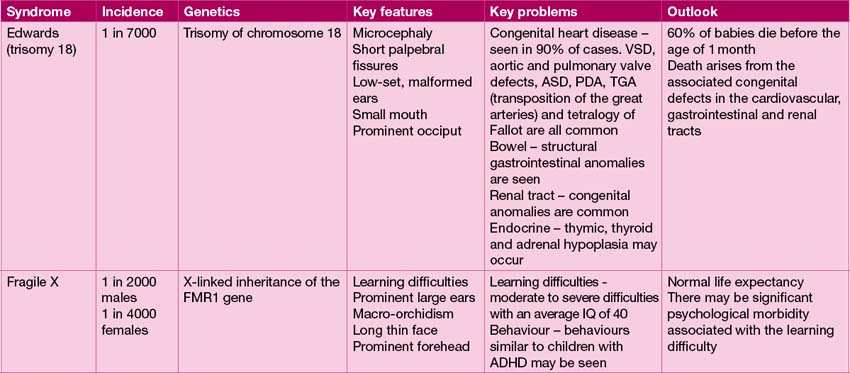

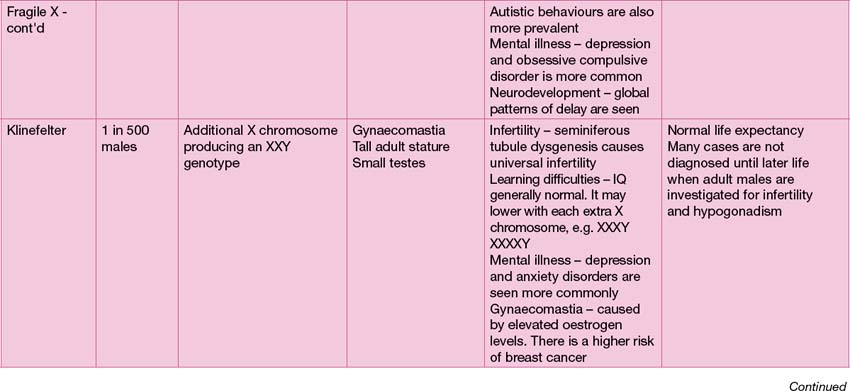

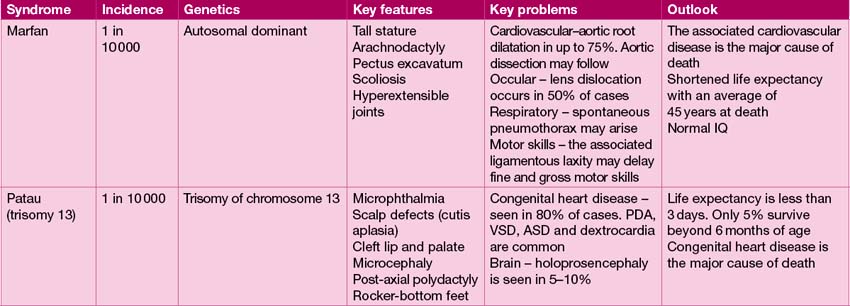

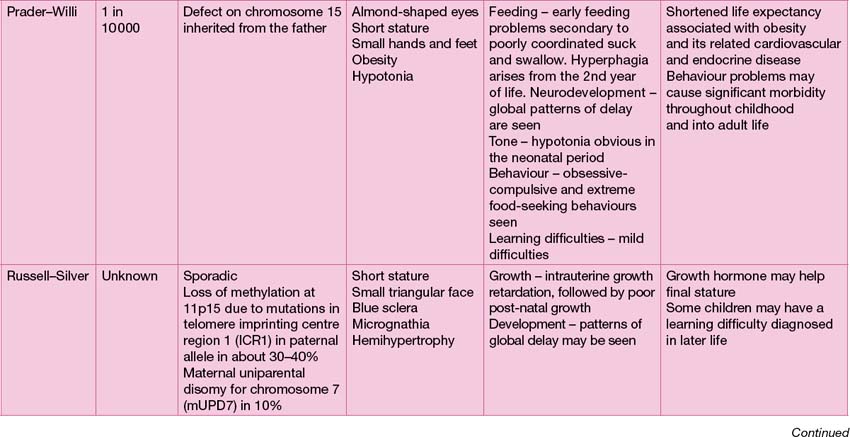

• Syndromes – a constellation of findings, which may themselves appear unrelated, may point to a syndromal diagnosis. Down syndrome (trisomy 21), is such an example. Other syndromes may not have a genetic origin, such as VACTERL (Vertebral anomalies, imperforate Anus, congenital Cardiac disease, Tracheo-oesophageal fistula, oEsophageal atresia, Renal anomalies and radial Limb defects). This arises from defective mesodermal development during embryogenesis.

Environmental factors

A number of environmental factors are implicated in the development of congenital abnormalities:

• Congenital infection, notably the ToRCH infections (Toxoplasma, Rubella, Cytomegalovirus and Herpes simplex), varicella and HIV (see Chapter 17, p. 256)

• Hyperthermia – fever secondary to infection, or use of hot tubs and sauna

• Radiation – studies of pregnant Japanese women exposed to radiation in Hiroshima and Nagasaki in World War 2 found that 28% miscarried, 25% of live born children died in infancy and 25% of survivors had CNS abnormalities – principally microcephaly and mental retardation

• Environmental chemicals – there is little definitive evidence about chemical exposure and congenital malformations, but growing circumstantial evidence implicates a number of chemicals as potential teratogens (e.g. arsenic, insecticides, lead, mercury, organic solvents, paint, polychlorinated biphenyls, toluene)

• Alcohol – fetal alcohol syndrome/fetal alcohol spectrum disorder may result from alcohol exposure (see below)

• Prescribed drugs – a number of drugs are known teratogens in pregnancy, but the severity of the underlying medical condition precludes their withdrawal. In general, drug use in pregnancy should be minimized, and known teratogens should be stopped prior to conception if at all possible (see Table 17.2, p. 249)

• Recreational drugs – drug use in pregnancy is often not disclosed, and often multiple drug exposures occur. Poor nutrition and concurrent alcohol use make attributing particular outcomes difficult. The best evidence is for cocaine use in pregnancy. Cocaine is a potent vasoconstrictor. Use is associated with miscarriage, intrauterine growth retardation, microcephaly, gastroschisis and genitourinary abnormalities.

Maternal disease

A number of maternal conditions have the potential to cause fetal malformations:

• Maternal diabetes – 2–5% of pregnancies are complicated by gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM), which accounts for 85–90% of diabetes in pregnancy. Often this is associated with maternal obesity. GDM arises during pregnancy, and is not associated with increased fetal malformations, but there is a high rate of miscarriage and fetal death, and neonatal morbidity and mortality from increased preterm birth, and complications of prematurity, coupled with macrosomia or growth retardation. Type 2 diabetes accounts for about 8–10%, with the remainder having type 1 diabetes. In contrast to GDM, hyperglycaemia during organogenesis may cause a x of 5–15%:

• Congenital adrenal hyperplasia – women affected by congenital adrenal hyperplasia need to take suppressive doses of hydrocortisone in pregnancy (or a suitable alternative steroid, e.g. prednisolone) to prevent virilization of a female fetus by the action of maternal androgens.

• Phenylketonuria (PKU) – phenylalanine is toxic to the fetus. Affected women must be scrupulous in their adherence to their diet and nutritional supplements to achieve near-normal phenylalanine concentrations. Spastic quadriplegia, microcephaly and mental retardation are the consequences of non-adherence. Use of supplemental tetrahydrobiopterin (a co-factor for phenylalanine hydroxylase, the deficient enzyme in PKU) may ease the dietary restriction, facilitating adherence.

• Maternal disease arising from the fetus – a fetus affected by long-chain 3-hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency produces toxic metabolites which cross the placenta and may result in severe maternal disease – severe pre-eclampsia, acute fatty liver of pregnancy, cholestasis of pregnancy and HELLP syndrome (Haemolysis, Elevated Liver enzymes and Low Platelets).

Fetal alcohol syndrome

As shown in Case 18.1, the fetus is very vulnerable to the effects of maternal alcohol ingestion. There is strong evidence that binge drinking is more detrimental than regular alcohol intake. The effects of alcohol on the fetus are threefold:

• Impaired growth – resulting in reduced head size, intrauterine growth retardation (usually symmetrical), post-natal growth failure with poor catch-up growth (sometimes compounded by growth hormone deficiency)

• Characteristic morphological abnormalities:

• Cognitive impairmentwith subsequent learning disability, behaviour problems (notably attention deficit disorder).

Inheritance of genetic disease

Autosomal inheritance

Autosomal dominant inheritance

Some proteins have important functions, and require both genes to be functional. Loss of one gene results in haploinsufficiency, e.g. mutations affecting lipoprotein lipase, resulting in familial hypercholesterolaemia, or neurofibromin in neurofibromatosis type 1. Alternatively, the mutated gene may make a protein which has detrimental effects (‘dominant negative’) as in osteogenesis imperfecta, when defective collagen fibres affect the structure of collagen helices, thus weakening the structure of bone. In achondroplasia, the abnormal gene, a fibroblast growth factor receptor, gains function, and is ‘switched on’ even in the absence of the fibroblast growth factor ligand, resulting in skeletal dysplasia. Such conditions are referred to as autosomal dominant. The recurrence risk is 1:2, and there is usually a family history, unless the mutation has arisen de novo, which is not infrequent (as in Case 18.3).

Genetic investigations

Antenatal testing

Sometimes, the need for genetic tests is evident before birth, due to a prior history of genetic disease, or the finding of morphological abnormalities on ultrasound, (see Chapter 17, p. 248). In early pregnancy, fetal sexing can be determined with high reliability on a maternal blood sample, between 7 and 9 weeks’ gestation. This may indicate the need for further investigations. For example, with a family history of haemophilia, an X-linked disorder, if the fetus is found to be a male, then chorionic villous sampling (CVS) at 10–12 weeks will permit molecular genetic diagnosis. For disorders that are not sex-specific, CVS is the initial investigation of choice. Later in pregnancy, amniocentesis and subsequent culture of fetal amniocytes will allow a detailed karyotype to be done. This is, however, more time consuming, and pregnancy is more advanced, making decisions about possible termination of pregnancy more problematic.

Neonatal testing

The newborn infant may be recognized to have dysmorphic features or abnormalities which indicate a possible genetic diagnosis. In this circumstance genetic investigation is indicated without delay as it may aid in management and decision-making, as in Case 18.2.

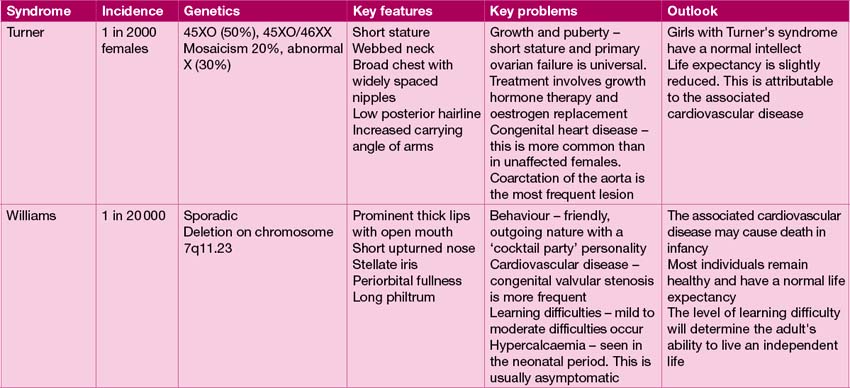

The finding of significant congenital abnormalities at birth should prompt genetic investigation. The nature of the problems will dictate the investigation performed (see Table 18.1).

| Clinical problem | Test |

|---|---|

| Urgent confirmation of a suspected chromosomal aneuploidy (e.g. Down syndrome) | Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) using appropriate probes |

| Urgent confirmation of genetic sex in an infant with ambiguous genitalia | FISH using appropriate probes |

| Confirmation of genetic status of a child born to a parent with a known balanced translocation | Karyotype (if not done antenatally) |

| Investigation of a child with multiple congenital anomalies | Low-resolution micro-array (or karyotype if array unavailable)* |

| Investigation of a specific genetic abnormality (e.g. cystic fibrosis) | Specific molecular genetic testing |

* Note that low-resolution micro-array is replacing the karyotype as a standard first-line investigation.

Genetic investigation of older children

Indications for genetic investigation of the older child are primarily:

• Unexplained learning or developmental difficulties (see Chapter 4, p. 29, for a list of investigations to be considered in the child with developmental delay)

• Short stature and/or delayed puberty

• Confirmation of specific diagnoses (e.g. confirmation of a clinical diagnosis of cystic fibrosis).

The family tree should include both sets of grandparents, and any other first- or second-degree relatives. Exploring the family tree needs to done thoroughly and accurately, but with sensitivity. For an example of a complex family tree, see Figure 1.1, p. 4.

Careful physical examination may reveal clues as to the diagnosis, such as the typical hockey-stick palmar crease of fetal alcohol syndrome. It is very important to look closely at the face, hair line, ears and inside the mouth. Enquire about birth marks. Look at height, weight and body proportions – some conditions are characterized by asymmetry, e.g. Russell–Silver syndrome (see Table 18.2). Formal ophthalmological examination may be helpful for some conditions (see Case 18.3). For other cases, radiographic investigation may be decisive (see Case 18.4).