Problem 4 Confusion in the postoperative ward

Answers

On attending the ward you will need to:

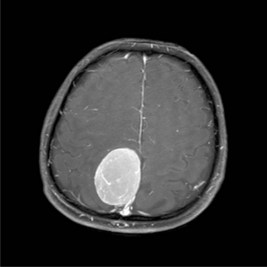

A.2 Postoperative confusion is common in the elderly and medically unfit, particularly following orthopaedic and cardiac surgery, occurring in up to 65% of cases. Surgical causes include atelectasis, postoperative wound infection or abscess, complications of anaesthesia and complications specific to the surgery. Postoperative confusion is an instance of delirium, and alongside these factors are the many predisposing and precipitating causes for acute confusion (Table 4.1). Most common are causes of cerebral hypoxia, drugs, infection, pain and iatrogenic factors.

Table 4.1 Predisposing and precipitating factors for delirium

| Predisposing Factors | Precipitating Factors |

|---|---|

A.3 The patient’s postoperative confusion is a delirium, variously known as acute confusional state, organic brain syndrome or toxic-metabolic encephalopathy. These are all terms for a clinical syndrome that represents a medical emergency, with significant morbidity and mortality as well as increased length and cost of admission. Delirium should be regarded as a sign of ‘brain failure’, an important signal of a systemic or cerebral emergency with multiple potential causes, that requires immediate diagnosis and treatment. Clinical features are listed in Box 4.1.

Box 4.1

Clinical features of delirium

A.5 There is no obvious postoperative complication or metabolic cause for this patient’s delirium.

Once delirium has occurred, treatment is according to the following principles:

Revision Points

Postoperative Confusion/Delirium

Precipitants may be only minor in the elderly with multiple predisposing factors, which include:

, http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/288890-overview. Overview of delirium

, http://www.health.gov.au/internet/alcohol/publishing.nsf/Content/treat-guide. Guidelines for the treatment of alcohol problems

, http://www.anesthesia-analgesia.org/content/102/4/1267.full. Postoperative delirium: the importance of pain and pain management