CHAPTER 52 Concepts of Endoscopic Sinus Surgery

Causes of Failure

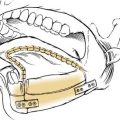

The extent of surgery is somewhat flexible in the overall concept of FESS—that is, the extent of surgery performed, the number of sinuses opened, and the inflamed diseased mucosa and bony partitions removed depend on the amount of disease identified on preoperative evaluation. It is therefore not a “one size fits all” operation but, rather, a procedure that is tailored to each patient’s set of findings from history, endoscopy, and radiologic evaluation. Optimally, surgery removes diseased bone and mucosa in the critical areas, with the recognition that the more distal linings of the maxillary, ethmoid, sphenoid, and frontal sinuses do not contain “condemned” mucosa, as was once taught. In the overall spectrum of radical to minimal surgery, the successful practitioner of FESS is probably somewhat radical in removing all bony partitions in areas of the ethmoid cavity involved in the disease process but is also able to preserve a mucosa-lined cavity on the skull base, medial orbital wall, and middle turbinate (Fig. 52-1).

It should be noted that the importance of the ostiomeatal unit was highlighted in the early years of FESS as a critical final common pathway in the disease process.1–3 Appropriate surgery in this critical area was found to have exceptionally good results in reversing patient symptoms, with positive outcomes in 80% to 90% of patients.4,5 However, over subsequent years, anatomic abnormalities in the ostiomeatal complex (OMC) came to be seen by some as the underlying cause of sinusitis, and not merely as a critical point in disease pathogenesis—that is, as a “bottleneck” for the sinonasal drainage pathways. The overemphasis of the importance of the role of the OMC in CRS led to an inappropriate overemphasis on surgically correcting abnormalities in the OMC. Anatomic variations should be regarded only as potential predisposing or potentiating factors in CRS, and not the underlying etiology of the disease; therefore appropriate surgery is only an adjunct treatment for chronic and recurrent rhinosinusitis, not primary therapy.

As discussed, surgery plays an adjunctive and important role in the treatment of rhinosinusitis, but medical therapy is the cornerstone of management of inflammatory disease.6 CRS is a multifactorial disease. The underlying pathogenesis can be broken into categories of causes that are environmental, generalized host factors, or local host factors. Environmental issues include smoking, allergy, mold/fungus exposure, and, possibly, emotional stress. General host factors include reactive airways disease, Samter’s triad, and genetic influences such as immunodeficiency. Local host factors include iatrogenic disease, nasal polyps, and diseases of poor mucus transport. Except in the cases of potential complications such as an expansile mucocele, the adjunctive procedure of surgical intervention (FESS) should be instituted when appropriate environmental control and medical therapy have failed. Continued medical therapy is usually required after surgery to avoid disease recurrence, and failure of the original surgery is often associated with abandonment of the basic concepts of FESS.

Extent of Surgery

Debate about the appropriate extent of surgery for CRS will most likely continue until the pathogenesis is better understood. However, the concept of “irreversibly diseased” or “condemned” mucosa that requires surgical removal is incorrect. In fact, Moriyama and colleagues7 have shown that denuding of bone results in extremely delayed healing. The bone may remain exposed for 6 months or more, and ciliary density may never return to normal at these sites. The underlying bone of an area of stripped mucosa is also prone to long-term inflammation and is a cause of failure, especially when associated with narrow areas such as the frontal recess. Therefore great emphasis should be placed on mucosal preservation in all sinuses during surgery, especially within the ethmoid sinus, owing to its central position in the paranasal sinuses.

The initial understanding of FESS has been modified, on the basis of continued improvement of the understanding of the disease process. Simply draining involved cells or sinuses may be insufficient in chronic disease. The surgery should be extended one stage beyond the diseased mucosa, which is identified either by computed tomography (CT) or at the time of surgery. Close endoscopic observation of postsurgical healing cavities led us to suspect that the underlying bone may play a significant part in the overall chronic disease process. The inflammatory aspects of the disease usually persist in localized areas, and the disease tends to recur at that same site.8–10 The inflammation of the mucosa typically resolves after the underlying bone is resected, but it will not improve if only the inflamed mucosa is removed. In experimental animals there is evidence of early bone involvement in sinusitis; chronic osteomyelitis and inflammation spread within the haversian canals of bone despite an inability to demonstrate the organisms within the bone. These clinical and experimental findings lead us to believe that resection of inflamed bone is important to the success of FESS. We hold that reduced viability and inflammation of the underlying bone may be a significant factor in the disease process, at least in more severe cases of CRS.

Surgical Indications in Inflammatory Disease

Chronic Rhinosinusitis

Several identified factors are associated with poor outcomes from FESS for CRS. Poor indicators of successful FESS include persistent environmental exposures after surgery, uncontrolled allergies, continuing chemical exposures, and smoking. Allergic patients with middle meatal and OMC disease may be relatively protected from their environmental allergens by their disease; after surgery, however, virgin mucosa is widely exposed to nasal airflow. Cigarette smokers have such bad outcomes with FESS that smoking is a relative contraindication to elective ESS. In patients who continue to smoke, a significantly greater than usual amount of granulation tissue develops over any areas of exposed bone, and the incidence of frontal recess stenosis is higher. In a long-term follow-up study, smoking was the most significant factor in the need for revision surgery and a significantly greater factor than prior surgical procedures, allergies, and asthma in determining the need for revision surgery.11–13

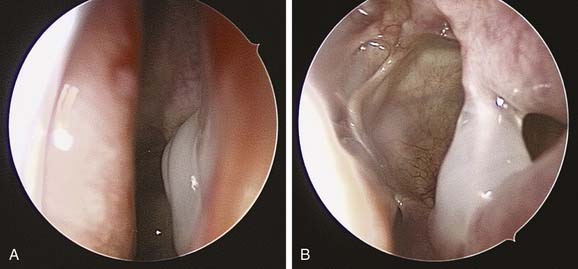

Mucoceles

In general, the functional endoscopic approach is of most benefit when extensive sinus disease results from a limited cause. Thus, frontal sinus obstruction resulting in an extensive frontal sinus mucocele with posterior table erosion is an ideal case for endoscopic intervention. Such an approach maintains the bony framework of the frontal recess and allows wide marsupialization with minimal morbidity. Indeed, in the presence of posterior table erosion, sinus obliteration is not a good alternative because of the difficulty of completely removing the lining mucosa from exposed dura (Fig. 52-2).

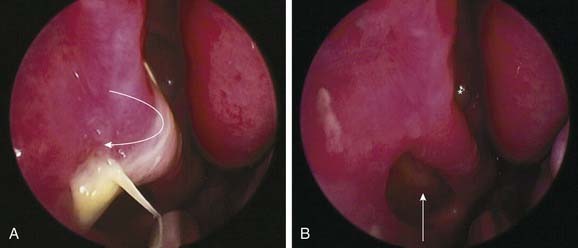

Fungal Rhinosinusitis

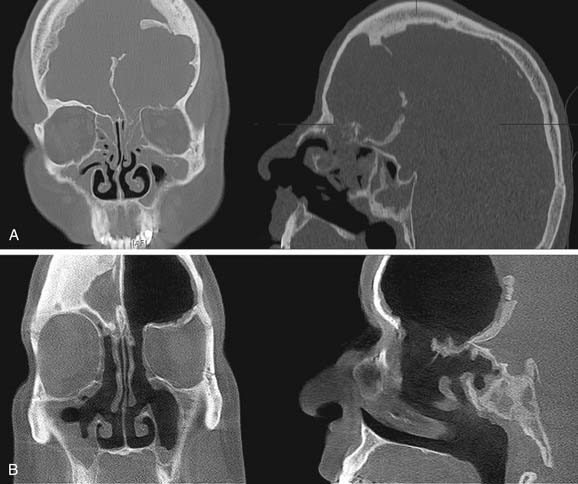

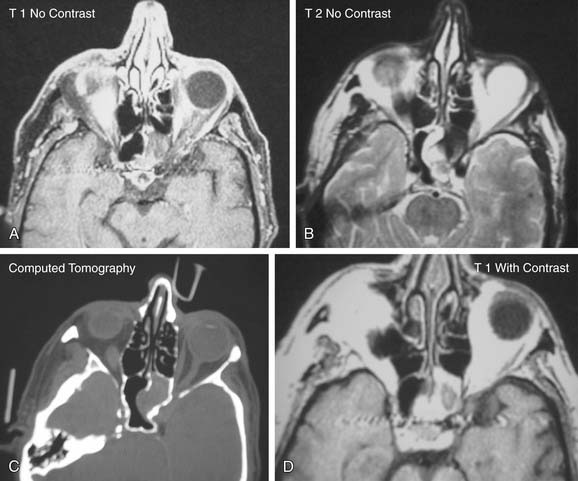

Allergic fungal rhinosinusitis may be associated with marked bone remodeling that may distort anatomic relations dramatically. In addition to dural exposure, erosion of bone and displacement of the optic nerve and carotid artery may occur when the disease involves the sphenoid or posterior ethmoid sinuses (Fig. 52-3). The aim of surgery in allergic fungal rhinosinusitis is complete removal of all of the inspissated material and polypoid mucosa. It is important to achieve complete removal of the intersinus partitions throughout the ethmoid and sphenoid cavities as well as a very wide middle meatal antrostomy and wide frontal sinusotomies. However, as in all surgery for inflammatory disease, care should be taken to maintain mucoperiosteal coverage of the bone within the cavity. Intensive medical therapy, both preoperative and postoperative, is important for success.14

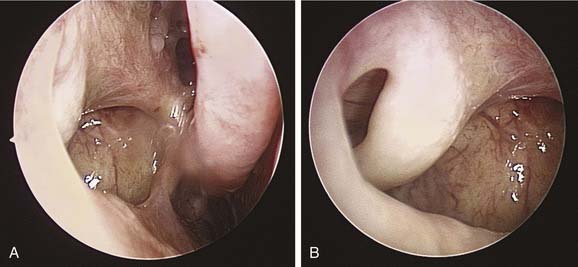

Surgical Indications for Tumors, Skull Base Defects, and Other Noninflammatory Lesions

Additional changes that have assisted in the development of extended endoscopic approaches include advances in instrumentation. The introduction of the EndoScrub Lens Cleaning System (Medtronic ENT, Jacksonville, FL), which enables the tip of the endoscope to be kept clean, has made it more possible to operate in the presence of bleeding. Fine slender 70-degree angulated drills, which perform simultaneous irrigation and suction, have significantly improved our ability to remove bone with precision through an endoscopic view (Fig. 52-4). Finally, the refinement of computer-assisted navigation, intraoperative CT scanning with real-time navigation, and CT–magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) merge technologies have allowed more accurate intraoperative localization of adjacent critical anatomy.15–17

Tumor control in benign lesions such as inverted papilloma requires precise preoperative imaging and endoscopic evaluation. If the tumor might be attached at a site beyond the reach of the endoscope, preoperative patient consent for an external procedure is necessary. At surgery careful attention is paid to remove or bur the underlying bone at the site of attachment. The dura and periorbita usually provide excellent barriers against spread of the lesion and should be left intact. Therefore, in areas of dural or periorbital exposure where the overlying bone has been eroded, only bipolar cautery rather than resection at the site or sites of attachment is performed. A major surgical aim in tumor surgery must be to create and maintain a widely patent surgical cavity to facilitate long-term endoscopic follow-up. Therefore, we advocate a very complete sphenoethmoidectomy, frontal sinusotomy, and very wide antrostomy in these cases. The nasolacrimal duct is sacrificed whenever necessary.18

Preoperative Evaluation and Management

Radiographic Evaluation

Computed Tomography

Presurgical evaluation of CT scans should be performed in a routine checklist fashion to ensure careful review of each area for anatomic variations (Table 52-1). Special care should be taken to evaluate the lateral cribriform plate lamella, because this medial part of the ethmoid roof is usually the thinnest part of the skull base and is exposed to potential trauma during frontal recess surgery. In general, the skull base is significantly thicker laterally than medially. Any areas of hyperostosis should be identified, because in these areas, the skull base can probably be approached with relative impunity.

Table 52-1 Computed Tomographic Evaluation before Functional Endoscopic Sinus Surgery

| Site | Evaluation |

|---|---|

| Skull base | Slope, height, erosions, areas of relative thickening and thinning |

| Medial orbital wall | Integrity, erosion, shape, infundibular size, and uncinate position |

| Ethmoid vessels | Position of anterior and posterior ethmoid vessels relative to skull base |

| Posterior ethmoid | Vertical height, presence of sphenoethmoidal (Onodi) cell |

| Maxillary sinus medial wall | Infraorbital ethmoid cells, accessory ostia |

| Sphenoid sinus | Relative sizes, position of intersinus septum, relationship to carotid arteries, and optic nerves |

| Frontal recess and frontal sinus | Frontal sinus pneumatization, frontal recess size, agger nasi and supraorbital ethmoid pneumatization, frontal sinus drainage |

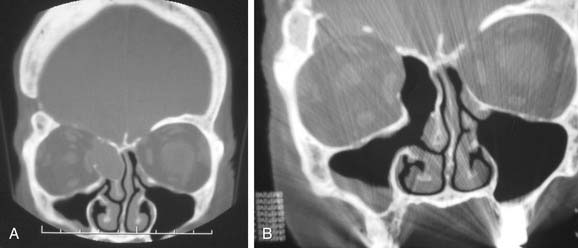

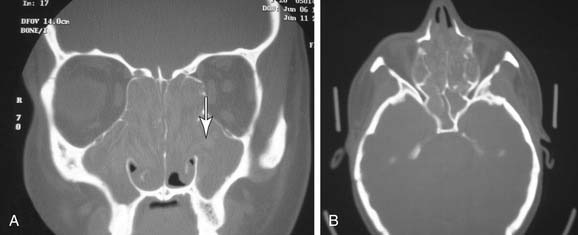

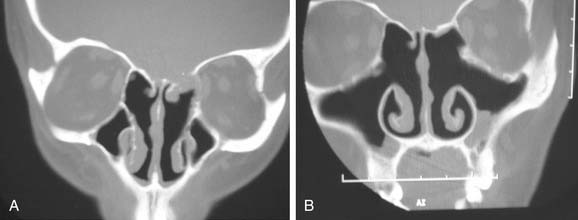

The medial orbital wall is evaluated for areas of erosion and for any irregularities (Fig. 52-5). The relative position of the uncinate process to the orbital wall and the presence of any infundibular atelectasis are noted so that inadvertent orbital entry will not occur during the initial infundibulotomy incision.

The anterior ethmoidal artery usually can be identified as a medial indentation (“nipple”) pointing medially from the medial orbital wall. This may be seen either at the level of the skull base or some distance below it (Fig. 52-6). The posterior ethmoidal artery is typically within the skull base and is significantly more difficult to recognize.

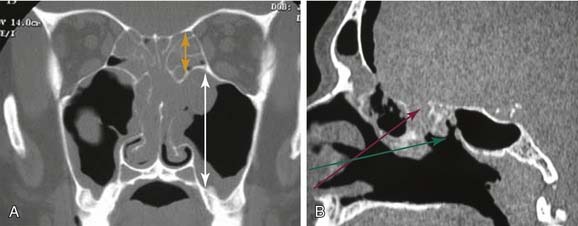

An evaluation of the vertical height of the posterior ethmoid should be performed. This is the vertical distance between the posteromedial roof of the maxillary sinus and the roof of the ethmoid sinus. This vertical height determines the working room available within the posterior ethmoid for access to the sphenoid sinus. Failure to recognize a narrow vertical height in this area may result in inadvertent intracranial entry (Fig. 52-7).

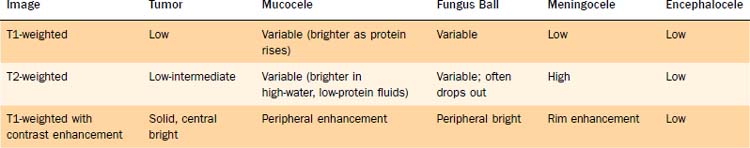

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Although CT is clearly the primary diagnostic modality for sinus disease, MRI is adjunctive and required in certain situations. MRI is essential when CT reveals disease adjacent to skull base erosion. In this situation, MRI identifies whether the erosion is caused by sinus disease or secondary to a prior skull base erosion or trauma with resultant meningoencephalocele. The evaluation of dehiscent areas becomes even more important when there are sphenoid erosions and the possibility of a carotid artery aneurysm. MRI also enables differentiation of sinus from intranasal soft tissue masses as well as of tumor from retained secretions (Table 52-2).

Concepts of Antrostomy

Whatever the size of antrostomy created, it is important that the opening communicates with the natural ostium to prevent failure of surgery. One of the more common causes of persistent maxillary sinus disease after surgery is the presence of a middle meatal antrostomy that does not connect with the natural ostium anteriorly.19 If the natural ostium is not opened, persistent disease may remain in the periostial area, with pooling of secretions and continued recurrent and persistent disease. Additionally, if the natural ostium does reopen and a noncontiguous middle meatal antrostomy is present, recirculation of mucus frequently occurs, with the mucus re-entering the maxillary sinus through the iatrogenic ostium. Such recirculating mucus will, almost of necessity, become more acutely infected from time to time. Confirming that a middle meatal antrostomy communicates with the natural ostium may not be easy. The bone of the uncinate process may become thickened after infection, and the ostium may become tightly closed and difficult to reopen. Additionally, there are no easy landmarks for the extent to which an antrostomy should be brought anteriorly. Inspection with a 45-degree or 70-degree telescope frequently is helpful in this regard and is definitely required to exclude with certainty the presence of a noncontiguous antrostomy (Figs. 52-8 and Fig. 52-9). Another anatomic abnormality that bears mention is the diseased infraorbital (Haller) cell, which even when opened may have residual osteitic partitions, creating persistent localized mucosal hypertrophy. Use of angled telescopes is important to evaluate the drainage pathways. Occasionally, when such bony partitions are clearly a cause of localized persistent disease and they are inaccessible from the intranasal route, a limited sublabial approach may be indicated for their removal (Fig. 52-10). Other long-term causes of antrostomy failure are osteoneogenesis from stripped mucosa, retained foreign body, and mucus draining into the sinus from persistent frontal recess inflammation.

Ethmoidectomy

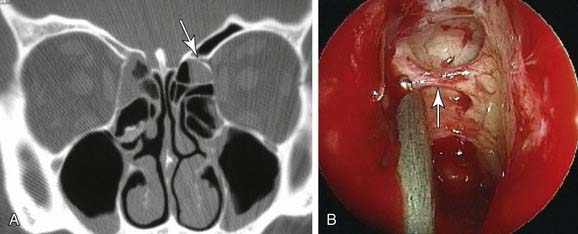

Iatrogenic disease can also include a meningocele or encephalocele. In a case in which a skull base dehiscence is identified and a meningocele is suspected, intrathecal injection of fluorescein before the surgery (0.1 mL of 10% fluorescein injected slowly in 10 mL of the patient’s own cerebrospinal fluid) can be considered, to help distinguish encephalocele from surrounding mucosa (Fig. 52-11).20

Sphenoidotomy

Before entry of the sphenoid sinus, it is advisable to re-review the radiographic anatomy in both the coronal and axial planes. In addition, the surgeon should review the course of the optic nerve and the carotid artery, especially if a sphenoethmoidal (Onodi) cell is present. The surgeon should also remember that the carotid artery is “clinically dehiscent” in 23% of sphenoid sinuses, making the potential for serious complication in this region significant (Table 52-3). The importance of preoperative diagnosis through radiologic studies must be emphasized (Fig. 52-12). Once the diagnosis is more firmly established and risk to surrounding structures is evaluated, multiple approaches to the sphenoid can be considered.

| Complication | Associated Structure(s) |

|---|---|

| Vascular hemorrhage | Posterior ethmoidal artery, internal carotid artery, cavernous sinus, sphenopalatine artery |

| Hematoma | Retrobulbar |

| Intracerebral injury | Cerebrospinal fluid leak, meningitis, cerebritis, abscess, brain injury, pituitary trauma |

| Fistula | Cavernous sinus: carotid artery |

| Cranial nerve (CN) injury | Optic nerve: blindness, pupillary defects |

| Oculomotor nerve (CN III): diplopia, pupillary defects | |

| Trochlear nerve (CN IV): diplopia, pupillary defects | |

| Abducens nerve (CN VI): diplopia, pupillary defects | |

| Trigeminal nerve (CN V1 to Vx): facial numbness |

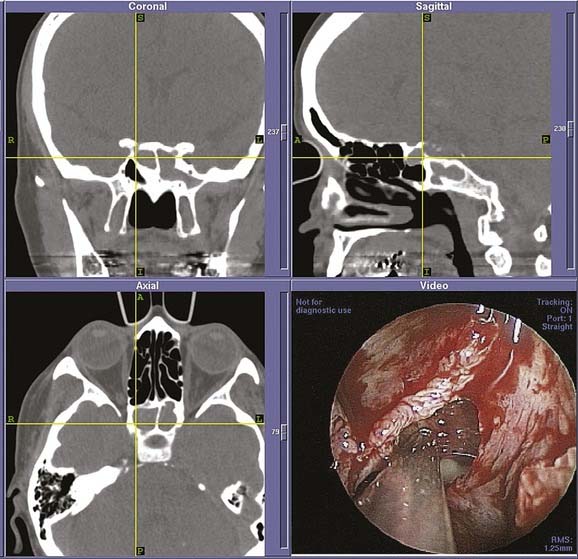

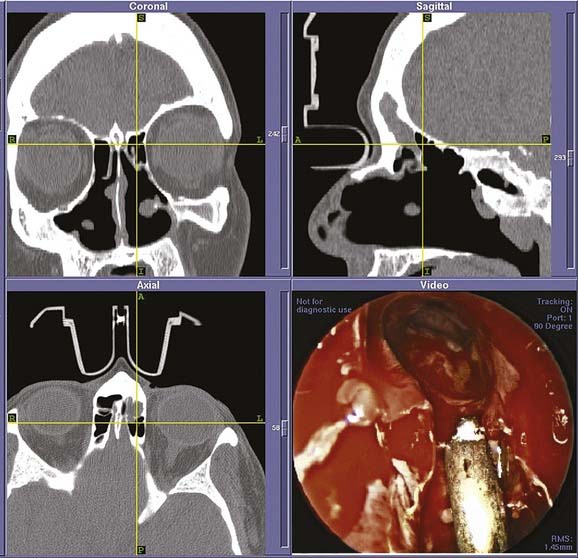

The transethmoid/transnasal approach is ideal when sphenoidotomy is combined with ethmoidectomy or when wide unilateral sphenoid exposure is required. Following complete ethmoidectomy, the sphenoid face, skull base, and superior turbinate are identified. In cases in which the last structure may be difficult to identify in the presence of severe disease, a ball-tipped seeker may be helpful in locating the superior meatus medially within the cavity. It can also be helpful to resect the posterior portion of the middle turbinate with a backbiter to further expose both the superior meatus and the turbinate. Once the appropriate structures are identified, the inferior third of the superior turbinate is sharply resected; then the natural ostium of the sinus is identified medial to it and is widened. It is important to create a very wide opening that extends to both the skull base and medial orbital wall to avoid the risk of postoperative stenosis (Figs. 52-13 and 52-14).

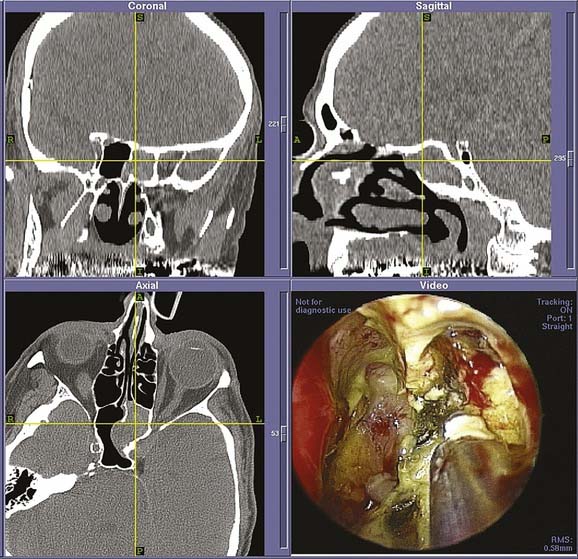

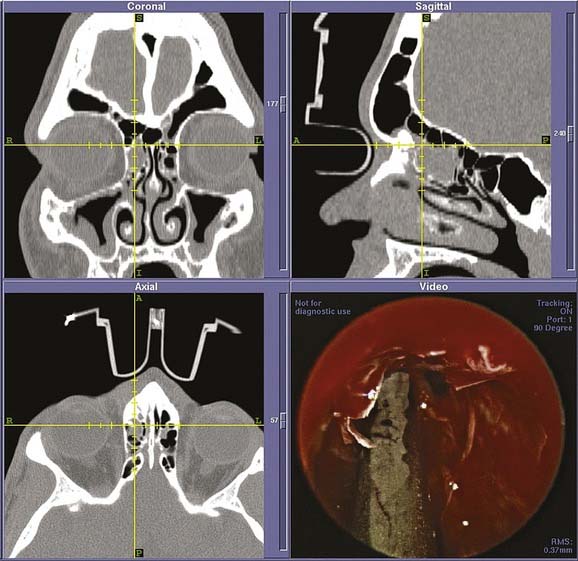

Figure 52-13. Intraoperative images from endoscopic sphenoethmoidectomy using an image-guided navigation system performed in the patient from Fig. 52-12. The cross hairs on the reformatted three-dimensional computed tomography scans (top, bottom left) denote placement of the probe as seen in the endoscopic view (bottom right). The remains of the fungal ball as well as the associated inflammation can be seen in the endoscopic view. After its removal, the patient had complete relief of symptoms with an uneventful postoperative period.

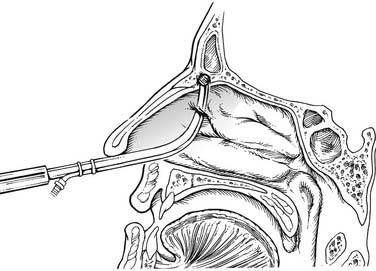

Frontal Sinusotomy

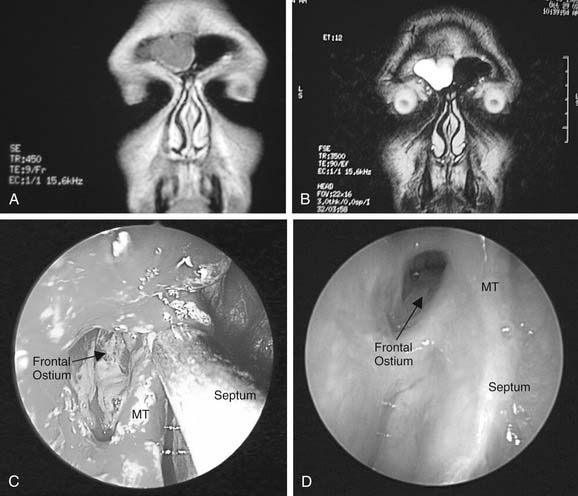

The concept therefore in FESS with respect to the frontal sinus is to work in a stepwise progression to remove all bony septae from cells present, in a procedure termed a frontal recess dissection. The initial step in frontal recess dissection involves identification of the appropriate boundaries and the drainage pathway of the frontal recess on CT scan, as well as correlation of this anatomy with the endoscopic view through a 45- or 70-degree telescope (Box 52-1 and Table 52-4). A fine malleable probe can be very helpful in locating the access to the frontal sinus. Once the inferior wall of the agger nasi cell is identified, the surgeon can resect it by sliding a 90-degree frontal sinus curette between the skull base and the posterior agger nasi cell wall and fracturing wall in an anterior and inferior direction (Fig. 52-15). Stammberger has very aptly described this gently performed maneuver as “uncapping the egg.” The remaining medial agger nasi cell wall is then removed. After the bone is fractured, the loose bony fragments can be teased out with a fine malleable hook and removed with giraffe forceps with preservation of the mucosa. Mucosal preservation is critically important during frontal recess dissection, but redundant mucosa can be removed with through-cutting forceps or gentle application of curved, powered dissection blades. In general, frontal sinus stents are less satisfactory in maintaining patency than meticulous postoperative care. However, if a stent is used, it should be made of a soft, conformable material.

| Medial | Superior attachment of the middle turbinate |

| Lateral | Lamina papyracea |

| Superior | Internal os of the frontal sinus |

| Anterior | Posterior buttress nasal spine—nasofrontal “beak” |

| Posterior | Superior extension of the ethmoid bulla to the skull base |

| Inferior | Nasal communication of the frontal recess |

Frontal cells originate as anterior ethmoid cells that pneumatize into the frontal recess, creating the potential for compromise of the frontal sinus outflow tract and thus serving as a significant potential cause of persistent disease.21 Because these are the second most anterior of the ethmoid cells, the origins of the frontal cells are located posterior to the agger nasi cell. Each frontal cell then pneumatizes superior to the agger nasi cell into the frontal recess and up into the frontal sinus, where it can cause frontal recess obstruction. A classification of four types of frontal sinus cells has been described, and the nomenclature for them expresses the distance they pneumatize into the frontal sinus, from a type I cell, which is just above the agger nasi cell, to a type IV cell, which pneumatizes completely into the frontal sinus itself. However, for a surgeon performing ESS, the relationship of the cell to the opening of the frontal sinus outflow tract is typically more important than the extent of the cell within the frontal sinus. The surgeon best determines this relationship by using triplanar CT reconstructions or, even better, by scrolling through the triplanar “cuts” on an image guidance system screen until he or she has developed a true three-dimensional conceptualization of the anatomy and how it will appear endoscopically. Frontal recess obstruction by frontal cells occurs in a similar fashion to that of obstruction of an agger nasi cell; that is, edema in very small, tight pathways or in an iatrogenic scar after surgery can close off the frontal recess.

If the uncinate process inserts on the medial orbit wall, the ethmoid infundibulum will end in a blind pocket called a recessus terminalis. This common anatomic variation (occurring in up to 50% of people) forces the frontal sinus drainage pathway down the medial surface of the uncinate process and thereby directly into the middle meatus. Because of the proximity of the downsloping skull base, dissection of this variant can be tricky, and failure to identify and meticulously dissect this structure is a common cause of surgical failure (Fig. 52-16).22

In all instances of frontal recess dissection, external approaches ranging from frontal sinus trephine to osteoplastic flap can be used as an adjunct to allow access to disease and completion of a thorough frontal recess dissection. The extended frontal sinus approaches, Draf IIB (Fig. 52-17) and Draf III (or transseptal frontal sinusotomy or modified Lothrop approach), have also offered new possibilities for the management of frontal sinus disease.23–25 In particular, the combination of a Draf III approach with an osteoplastic procedure enables the management of frontal sinus lesions such as tumors without the necessity of frontal sinus obliteration. This combination of endoscopic and external approach means that the big disadvantage of obliteration, the loss of subsequent accurate imaging, is eliminated and the frontal sinus can be monitored directly via endoscope, with either angled rigid scopes or a flexible endoscope, during routine follow-up.

Turbinate Management

At the end of the procedure, attention should be directed toward the middle turbinate to help ensure a good postoperative result. Any exposed bone should be removed. A floppy middle turbinate should be stabilized; frequently this is done via a controlled scar to the nasal septum. At 1 month or more in the postoperative period, the adhesions between the septum and middle turbinate may be lysed to return the middle turbinate to its normal profile.26 Another option to stabilize the middle turbinate and prevent a lateralized one is to suture the turbinate to the septum with an absorbable suture. Routine amputation or resection of the middle turbinate is not recommended because it alters whatever is left of normal physiologic actions of the turbinate and because the stump often lateralizes anyway, causing iatrogenic frontal sinus disease.

Postoperative Medical Management and Débridement

Long-term follow-up and medical management are required for patients who undergo revision surgery. Because patients who have had surgery are at risk for persistence of disease, and because persistent disease is frequently asymptomatic in the early postoperative period, the critical factor guiding care is the appearance of the cavity on nasal endoscopy rather than symptoms. The postoperative care for a patient who has had revision surgery can easily last at least a year with a decreasing frequency of visits, but in severe disease it is commonly even longer.27 Over this period, while the inflammation is settling down, multiple courses of oral steroids and culture-directed antibiotics may be required. The occurrence of a viral upper respiratory infection during this period may need additional attention, with either prophylactic antibiotic coverage or a short course of oral steroids to manage the hyperreactive mucosa. However, over time, the mucosa typically stabilizes and returns to more normal function. Symptoms should be monitored closely. Pain and pressure in the postoperative period are uncommon and should prompt further investigation, because they are frequently signs of persistent inflammation. Postnasal discharge is common, resolving slowly and sometimes incompletely. Loss of olfaction is a sensitive sign of return of disease and also an indication for repeat endoscopic evaluation and, possibly, additional medical management.

Patients undergoing revision surgery may require endoscopic follow-up for years if a stable cavity is not obtained. In terms of the goal of disease resolution, it is much more effective to intervene earlier in the disease process with débridement, steroids, and antibiotics than to wait until the patient requires another revision procedure for removal of hyperplastic or polypoid disease. In the setting of well-performed surgery, the appearance of mucosal hypertrophy or inflammation or any return of symptoms, especially loss of olfaction or nasal congestion, requires aggressive medical treatment. However, in all situations, the goal is to minimize oral steroid therapy and replace it with a combination of topical and mechanical treatments whenever possible. In addition to environmental and allergy management, adjunctive therapy with antihistamines, antileukotrienes, and anti–immunoglobulin E monoclonal antibody may be considered. Imaging with another CT scan is not typically required as long as a nicely patent cavity is achieved. However, postoperative CT can be help evaluate whether any cells were missed in the original procedure or whether frontal stenosis has reccurred.28–30

Conclusion

The concept of functional endoscopic sinus surgery is to surgically remove inflamed tissue and bone from critical points in the mucociliary clearance pathways. In inflammatory disease, it is one tool of an armamentarium of therapies utilized in an overall management aimed at the inflammation and the inciting factors causing that inflammation in the nose and sinus cavities. However, the same surgical techniques have been extended to manage a variety of neoplastic and other lesions of the nose and skull base, and continued refinements in technique and instrumentation will further expand the opportunities for these techniques in the years ahead.31

Bent JP, Cuilty-Siller C, Kuhn FA. The frontal cell as a cause of frontal sinus obstruction. Am J Rhinol. 1994;8:185-191.

Bolger WE, Kuhn FA, Kennedy DW. Middle turbinate stabilization after functional endoscopic sinus surgery: the controlled synechia technique. Laryngoscope. 1999;109:1852-1853.

Chandra RK, Kennedy DW, Palmer JN. Endoscopic management of failed frontal sinus obliteration. Am J Rhinol. 2004;18(5):279-284.

Cohen NA, Kennedy DW. Revision endoscopic sinus surgery. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2006;9(3):417-435.

Cohen NA, Kennedy DW. Endoscopic sinus surgery: where we are—and where we’re going. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2005 Feb;13(1):32-38.

Kennedy DW, Senior BA, Gannon FH, et al. Histology and histomorphometry of ethmoid bone in chronic rhinosinusitis. Laryngoscope. 1998;108:502-507.

Kennedy DW. Prognostic factors, outcomes, and staging in ethmoid sinus surgery. Laryngoscope. 1992;102:1-18.

Kennedy DW, Zinreich SJ, Rosenbaum AE, et al. Functional endoscopic sinus surgery: theory and diagnostic evaluation. Arch Otolaryngol. 1985;111(9):576-582.

Khalid AN, Hunt J, Perloff JR, et al. The role of bone in chronic rhinosinusitis. Laryngoscope. 2002;112(11):1951-1957.

Lanza DC, O’Brien DA, Kennedy DW. Endoscopic repair of cerebrospinal fluid fistulae and encephaloceles. Laryngoscope. 1996;106:1119-1125.

Lee JT, Kennedy DW, Palmer JN, et al. The incidence of concurrent osteitis in patients with chronic rhinosinusitis: a clinicopathological study. Am J Rhinol. 2006;20(3):278-282.

Marple BF. Allergic fungal rhinosinusitis: current theories and management strategies. Laryngoscope. 2001;111:1006-1019.

McLaughlin RB, Hwang PH, Lanza DC. Endoscopic trans-septal frontal sinusotomy: the rationale and results of an alternative technique. Am J Rhinol. 1999;13(4):279-287.

Moriyama H, Yanagi K, Otori N, et al. Healing process of sinus mucosa after endoscopic sinus surgery. Am J Rhinol. 1996;10:61-66.

Orlandi RR, Kennedy DW. Revision endoscopic frontal sinus surgery. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2001;34:77-90.

Palmer JN. Bacterial biofilms: do they play a role in chronic sinusitis? Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2005;38(6):1193-1201.

Palmer JN, Kennedy DW. Medical management in functional endoscopic sinus surgery failures. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2003;11(1):6-12.

Perloff JR, Gannon FH, Bolger WE, et al. Bone involvement in sinusitis: an apparent pathway for the spread of disease. Laryngoscope. 2000;110:2095-2099.

Senior BA, Kennedy DW, Tanabodee J, et al. Long-term results of functional endoscopic sinus surgery. Laryngoscope. 1998;108:151-157.

Stammberger H. Endoscopic endonasal surgery—concepts in treatment of recurring rhinosinusitis: part I. Anatomic and pathophysiologic considerations. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1986;94(2):143-147.

Stammberger H. Endoscopic endonasal surgery—concepts in treatment of recurring rhinosinusitis: part II. Surgical technique. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1986;94(2):147-156.

Tran KN, Beule AG, Singal D, et al. Frontal ostium restenosis after the endoscopic modified Lothrop procedure. Laryngoscope. 2007;117(8):1457-1462.

Weber R, Draf W, Kratzsch B, et al. Modern concepts of frontal sinus surgery. Laryngoscope. 2001;111(1):137-146.

Woodworth BA, Bhargave GA, Palmer JN, et al. Clinical outcomes of endoscopic and endoscopic-assisted resection of inverted papillomas: a 15-year experience. Am J Rhinol. 2007;21(5):591-600.

Woodworth BA, Chiu AG, Cohen NA, et al. Real-time computed tomography image update for endoscopic skull base surgery. J Laryngol Otol. 2008;122(4):361-365. 2007

1. Kennedy DW, Zinreich SJ, Rosenbaum AE, et al. Functional endoscopic sinus surgery: theory and diagnostic evaluation. Arch Otolaryngol. 1985;111(9):576-582.

2. Stammberger H. Endoscopic endonasal surgery—concepts in treatment of recurring rhinosinusitis: part I. Anatomic and pathophysiologic considerations. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1986 Feb;94(2):143-147.

3. Stammberger H. Endoscopic endonasal surgery—concepts in treatment of recurring rhinosinusitis: part II. Surgical technique. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1986 Feb;94(2):147-156.

4. Levine HL. Functional endoscopic sinus surgery: evaluation, surgery, and follow-up of 250 patients. Laryngoscope. 1990;100:79-84.

5. Senior BA, Kennedy DW, Tanabodee J, et al. Long-term results of functional endoscopic sinus surgery. Laryngoscope. 1998;108:151-157.

6. Palmer JN, Kennedy DW. Medical management in functional endoscopic sinus surgery failures. Curr Opin Otolarygol Head Neck Surg. 2003;11(1):6-12.

7. Moriyama H, Yanagi K, Otori N, et al. Healing process of sinus mucosa after endoscopic sinus surgery. Am J Rhinol. 1996;10:61-66.

8. Kennedy DW, Senior BA, Gannon FH, et al. Histology and histomorphometry of ethmoid bone in chronic rhinosinusitis. Laryngoscope. 1998;108:502-507.

9. Perloff JR, Gannon FH, Bolger WE, et al. Bone involvement in sinusitis: an apparent pathway for the spread of disease. Laryngoscope. 2000;110:2095-2099.

10. Khalid AN, Hunt J, Perloff JR, et al. The role of bone in chronic rhinosinusitis. Laryngoscope. 2002;112(11):1951-1957.

11. Kennedy DW. Prognostic factors, outcomes, and staging in ethmoid sinus surgery. Laryngoscope. 1992;102:1-18.

12. Lee JT, Kennedy DW, Palmer JN, et al. The incidence of concurrent osteitis in patients with chronic rhinosinusitis: a clinicopathological study. Am J Rhinol. 2006;20(3):278-282.

13. Tran KN, Beule AG, Singal D, et al. Frontal ostium restenosis after the endoscopic modified Lothrop procedure. Laryngoscope. 2007;117(8):1457-1462.

14. Marple BF. Allergic fungal rhinosinusitis: current theories and management strategies. Laryngoscope. 2001;111:1006-1019.

15. Roth M, Lanza DC, Zinreich J, et al. Advantages and disadvantages of three-dimensional computed tomography intraoperative localization for functional endoscopic sinus surgery. Laryngoscope. 1995;105:1279-1286.

16. Fried MP, Kleefield J, Gopal H, et al. Image-guided endoscopic surgery: results of accuracy and performance in a multicenter clinical study using an electromagnetic tracking system. Laryngoscope. 1997;107:594-601.

17. Woodworth BA, Chiu AG, Cohen NA, et al. Real-time computed tomography image update for endoscopic skull base surgery. J Laryngol Otol. 2008;122(4):361-365.

18. Woodworth BA, Bhargave GA, Palmer JN, et al. Clinical outcomes of endoscopic and endoscopic-assisted resection of inverted papillomas: a 15-year experience. Am J Rhinol. 2007;21(5):591-600.

19. Parsons DS, Stevens FE, Talbot AR. The missed ostium sequence and the surgical approach to revision functional endoscopic sinus surgery. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 1996;29:69-83.

20. Lanza DC, O’Brien DA, Kennedy DW. Endoscopic repair of cerebrospinal fluid fistulae and encephaloceles. Laryngoscope. 1996;106:1119-1125.

21. Bent JP, Cuilty-Siller C, Kuhn FA. The frontal cell as a cause of frontal sinus obstruction. Am J Rhinol. 1994;8:185-191.

22. Orlandi RR, Kennedy DW. Revision endoscopic frontal sinus surgery. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2001;34:77-90.

23. Weber R, Draf W, Kratzsch B, et al. Modern concepts of frontal sinus surgery. Laryngoscope. 2001;111(1):137-146.

24. McLaughlin RB, Hwang PH, Lanza DC. Endoscopic trans-septal frontal sinusotomy: the rationale and results of an alternative technique. Am J Rhinol. 1999;13(4):279-287.

25. Chandra RK, Kennedy DW, Palmer JN. Endoscopic management of failed frontal sinus obliteration. Am J Rhinol. 2004;18(5):279-284.

26. Bolger WE, Kuhn FA, Kennedy DW. Middle turbinate stabilization after functional endoscopic sinus surgery: the controlled synechia technique. Laryngoscope. 1999;109:1852-1853.

27. Palmer JN. Bacterial biofilms: do they play a role in chronic sinusitis? Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2005;38(6):1193-1201.

28. Bhattacharyya N. Clinical outcomes after revision endoscopic sinus surgery. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;130(8):975-978.

29. Litvack JR, Griest S, James KE, et al. Endoscopic and quality-of-life outcomes after revision endoscopic sinus surgery. Laryngoscope. 2007;117(12):2233-2238.

30. Cohen NA, Kennedy DW. Revision endoscopic sinus surgery. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2006;9(3):417-435.

31. Cohen NA, Kennedy DW. Endoscopic sinus surgery: where we are—and where we’re going. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2005;13(1):32-38.

to

to  that of a standard head CT scan, and therefore worth the added radiation when one considers the clinical information garnered, which can then be uploaded to the image guidance system. We suspect the future will combine the advantages of intraoperative CT scanning with computer-assisted surgery in one machine.

that of a standard head CT scan, and therefore worth the added radiation when one considers the clinical information garnered, which can then be uploaded to the image guidance system. We suspect the future will combine the advantages of intraoperative CT scanning with computer-assisted surgery in one machine.