Chapter 31 Conception control

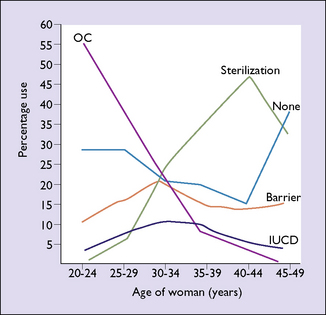

Contraceptive choices now available permit the woman, or the couple, to choose the most appropriate contraceptive for their particular circumstances. Younger women usually prefer oral contraceptives or expect their male partners to use condoms, whereas older women are more inclined to choose the intrauterine device (IUCD) or a permanent method of birth control, such as tubal ligation or a vasectomy in her partner (Fig. 31.1).

The result is expressed as the failure rate per 100 woman years (HWY).

Table 31.1 shows the effectiveness of various contraceptive methods in preventing pregnancy.

Table 31.1 Ranking of contraceptive methods by rate of effectiveness

| Failure Rates per 100 HWY | ||

|---|---|---|

| Group A | Most effective | |

| Tubal ligation/ vasectomyCombined oralContinuous progesterone | 0.005–0.04 | |

| Combined oral | 0.005–0.30 | |

| Continuous progesterone | 0.07 | |

| Group B | Highly effective | |

| IUCD | 0.5–3.5 | |

| Depot progestogen | 1.5–2.3 | |

| Diaphragm or comdom | ||

| All users | 4.0–7.0 | |

| Highly motivated | 1.5–3.0 | |

| Periodic abstinence | ||

| All users | 10.0–30.0 | |

| Highly motivated | 2.5–5.0 | |

| Group C | Less effective | |

| Coitus interruptus | 30.0–40.0 | |

| Vaginal foam or cream | 30.0–40.0 | |

| Group D | Least effective | |

| Postcoital douche | 45.0 | |

| Prolonged breastfeeding | 45.0 |

REVERSIBLE METHODS OF CONTRACEPTION USED BY THE COUPLE

Periodic abstinence

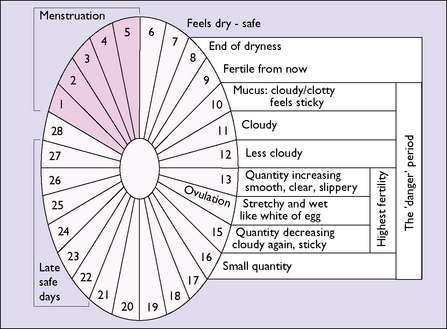

The woman is taught to detect the presence of mucus at the vaginal entrance each morning (before any sexual arousal). Three types of mucus can be detected and, from this, the days on which sexual intercourse can take place can be calculated while to some extent avoiding the chance of an unwanted pregnancy (Fig. 31.2). The compliance of the man is essential if pregnancy is to be avoided.

Coitus interruptus

Withdrawal, or coitus interruptus, is the oldest form of birth control apart from induced abortion. With the development of more modern contraceptives its frequency has declined, but it is still the preferred method in some sections of society. Its reliability for preventing pregnancy depends on the ability of the man to recognize the pre-ejaculatory phase and his agility in withdrawing his penis from the woman’s vagina before ejaculation. Because of these constraints, the efficacy of coitus interruptus in preventing an unwanted pregnancy is rather low (see Table 31.1).

REVERSIBLE METHODS OF CONTRACEPTION USED BY MEN

REVERSIBLE METHODS OF CONTRACEPTION USED BY WOMEN

Women have more choices of reversible or temporary contraception than men. They may choose:

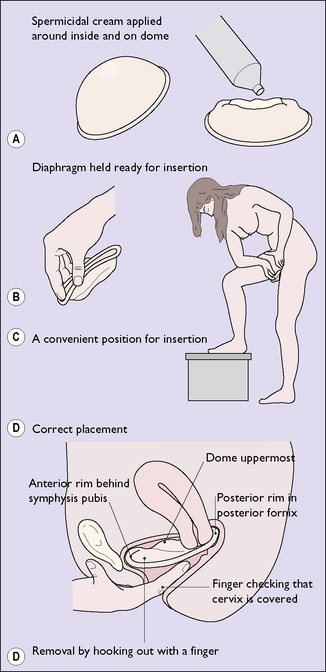

Barrier methods

Hormonal contraceptives

Contraindications to the prescription of COCs

Non-contraceptive benefits of COCs

Clinical side-effects of COCs

Circulatory disease

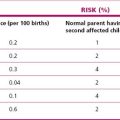

Thromboembolism is slightly more common in COC users, although the risk is small (from 4–6 to 10–15 per 100 000 women per year). The increase is due to an increase in fibrinogen concentration and of factors II, VII, IX, X and XII, and a decrease in antithrombin III. There is a concomitant increase in fibrinolysis, but it does not equal the coagulation changes. The risk is increased in smokers and in obese women. If these two variables are excluded the relative risk of developing thromboembolism in a woman taking low-dose COCs is small. (Table 31.2).

| Risk (per 100 000 Women) | |

|---|---|

| Healthy women who neither smoke nor take sex hormones | 4–6 |

| Women taking low-dose COCs with 2nd generation progestogens | 10–15 |

| Women taking COCs containing 3rd generation progestogens | 20–30 |

| Pregnant and parturient women | 50–60 |

Other clinical conditions occurring in women using COCs

Non-oestrogen hormonal contraceptives

Progesterone-only pill (POP) – the mini-pill

This oral contraceptive is a good choice for women who have contraindications for COCs, or who are breastfeeding. It is an alternative for some diabetic women, women who have risk factors for cardiovascular disease, women who have hypertension related to COCs or who need control by antihypertensives, and some migraine sufferers. The POP is associated with BTB and unpredictable menstruation in about one in four users. The failure rate (pregnancy rate) is shown in Table 31.1.

Subdermal implants

The synthetic progestagen etonorgestrel (Implanon) is placed under the skin of the inner aspect of the non-dominant upper arm under local anaesthetic. The 68 mg implant is effective for 3 years and ovulation usually returns within 1 month of removal. It is a highly effective contraceptive agent with a Pearl Index of <0.07/100 woman years (Fig 31.5). As with other progestogen formulations such implants may provoke irregular episodes of uterine bleeding; oligomenorrhoea 26%, amenorrhoea 21%, frequent or prolonged bleeding 18% and normal menstrual cycle in 35%. Weight gain, breast tenderness and mood changes occur in 5–10% of women, and acne may be improved. If it is inserted in the first 5 days of the woman’s cycle then it is effective immediately, otherwise it is important to make sure the woman is not already pregnant before insertion and then to use other contraception for 7 days.

Prescribing hormonal contraceptives

The history is taken and the woman is examined as described in Chapter 1. The choices of hormonal contraceptives available may be discussed with the woman, although often she has a good idea of the one she would prefer. She should be advised to read and to follow the instructions contained in the packet. Some doctors provide a pamphlet that reinforces these instructions.

Postcoital contraception

If a woman has unprotected sexual intercourse at ovulation time she has two choices. The first is to wait and see if she misses a menstrual period and then have an immunological pregnancy test. If this is positive, she can then choose to continue with the pregnancy or to have an induced abortion (see p. 105). The second choice is to use a form of postcoital contraception, provided she seeks help within 72 hours. Four methods are available:

Intra-uterine device

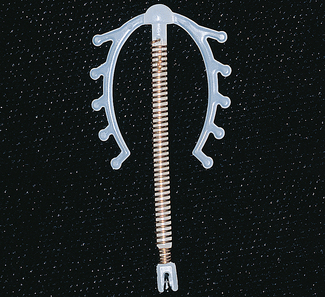

A satisfactory IUCD should be easy to introduce, easy to remove, and have few side-effects and a high degree of efficiency in preventing pregnancy. In the 1980s, a series of legal actions against manufacturers led to the removal from the market of most IUCDs, and today only three types remain. Two of the devices have fine copper wire surrounding the stem, which permits a smaller device to be used and reduces some of the side-effects (Fig. 31.6). The third type contains levonorgestrel in its stem (Fig. 31.7). In the first 4 months of use some women have unpredictable episodes of spotting or bleeding, and may develop the unacceptable side-effects of negative mood change, acne and, sometimes, weight gain. After this time the levonorgestrel IUCD reduces the menstrual flow, controlling menorrhagia in women who have this menstrual disturbance; it may also cause amenorrhoea. This device may be chosen by women in their 40s who would otherwise consider tubal ligation.

Advantages of the IUCD

The IUCD requires only a single decision to have the device introduced into the uterus and, unless problems arise, will prevent pregnancy for 3–8 years (depending on the device). It is highly effective in preventing pregnancy (see Table 31.1).

Adverse effects of IUCDs

Pelvic inflammatory disease

Pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), or pelvic infection, is discussed in detail in Chapter 33. The background incidence of PID in the community is 1 per 100 women aged 15–45 per year. It has been claimed that the IUCD increases the chance of developing PID. A recent meta-analysis has shown that this only applies if the infection occurs within the first month of insertion in women who have symptomless cervical infections due to Chlamydia trachomatis, Neisseria gonorrhoeae or, rarely, polymicrobial infection at the time of insertion.

Contraindications to the use of an IUCD

PERMANENT METHODS OF BIRTH CONTROL

Vasectomy

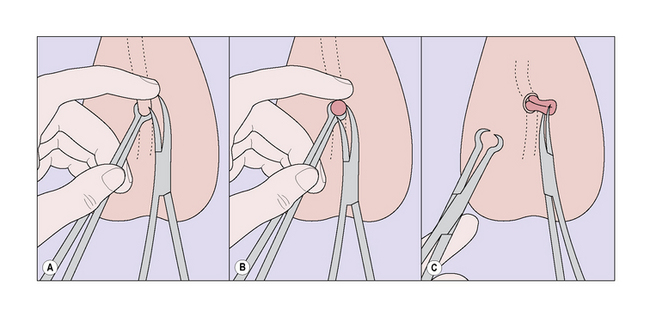

The vasectomy operation is simple to perform, effective, and attended by little pain or inconvenience, particularly if the no-scalpel technique, developed in China, is used (Fig. 31.8). A few men develop scrotal swelling, bruising or a small haematoma, all of which settle quickly.

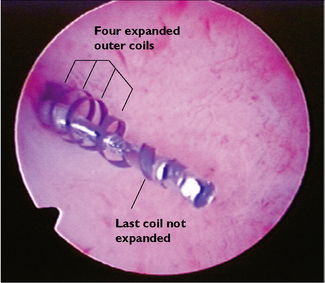

Hysteroscopically placed tubal occlusive device

The Selective Tubal Occlusive Device (Essure; Fig. 31.9) is a microcoil that is placed hysteroscopically directly into the tubal ostia under local anaesthesia. The localized inflammatory response causes tubal occlusion. The device appears to be well tolerated and clinical trials are reporting 85% successful placement and 99.8% efficacy.