Comprehensive Management of Individuals in the Intensive Care Unit

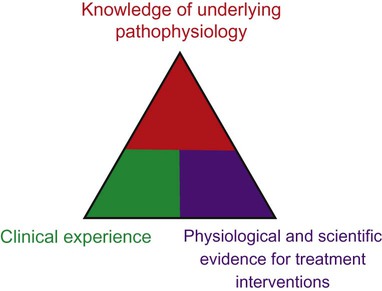

The thrust toward evidence-based practice in health care and the development of conceptual bases for practice have had major implications for cardiovascular and pulmonary physical therapy in the ICU.1–4 Superior knowledge of cardiovascular and pulmonary physiology, pathophysiology, pharmacology, multisystem dysfunction and its medical management, and ICU equipment and changing technology is essential. Clinical decision making in the ICU and rational management of patients is based on a tripod approach: knowledge of the underlying pathophysiology and basis for general care; knowledge of the physiological and scientific evidence for treatment interventions; and clinical reasoning and decision making in prioritizing treatments, prescribing their parameters, and performing serial evaluation to assess outcomes and further modify treatment (Figure 33-1). High-quality care is a function of these three areas of knowledge and expertise. Evidence-based practice and excellent problem-solving ability will optimize outcomes5 and maximize the benefit-to-risk ratio of cardiovascular and pulmonary physical therapy interventions.

Specialized Expertise of the Intensive Care Unit Physical Therapist

Effective clinical decision making and practice in the ICU demand specialized expertise and skill, including advanced, state-of-the-art knowledge in cardiovascular and pulmonary and multisystem physiology and pathophysiology and in medical, surgical, nursing, and pharmacological management (Box 33-1). Physical therapists in the ICU need to be first-rate diagnosticians and observers. Given the multitude of factors that contribute to impaired oxygen transport,6 the physical therapist needs to analyze these to define the patient’s specific oxygen transport deficits and problems. Optimizing oxygen delivery in the patient who is critically ill7 by exploiting noninvasive interventions is the priority.

Goals and General Basis of Management

1. Return the patient to his or her premorbid functional level or a higher level if possible

2. Reduce complications, morbidity, premature mortality, and length of ICU and overall hospital stay

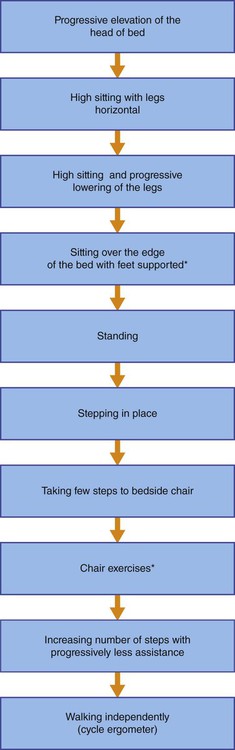

Many elements of the assessment of patients in the ICU are comparable to those for patients with acute conditions who are not critically ill but require respiratory support and mechanical ventilation (see Chapter 44). The primary difference is that for patients in the ICU the adequacy of the steps in the oxygen transport pathway are monitored closely, and the status and function of multiple organ systems are monitored in a serial (repeated at regular or judicious intervals) manner to observe trends over time so that treatment modifications can be titrated to the patient’s responses. Serial vital signs including pain and distress are recorded along with arousal and cognitive status, neuromuscular status, musculoskeletal status, and functional mobility. Assessment of functional mobility ranges from the smallest movement to walking (see Figure 33-2 and Box 33-4). Often it includes bed mobility, transfers to chair, and walking, which may require assistive devices. Related laboratory investigations are noted, including the electrocardiogram (ECG), radiographs, scans, blood work, blood sugar level, and fluid and electrolyte balance, and are followed closely to quickly detect improvement or deterioration so that treatment can be correspondingly modified.

Mechanical ventilation and its modes and parameters are described in Chapter 44. The ventilator settings including the fraction of inspired oxygen (FIO2) are important indicators of changes in the patient’s status and therefore must be included in the assessment and recorded at each treatment. Similarly, changes in FIO2 are important outcomes and indicators of treatment response. This information is used collectively in clinical decision making before, during, and after weaning from mechanical ventilation.

In patients who are medically stable, invasive mechanical ventilation is titrated judiciously to ensure that the patient is initiating breaths as much as possible, which facilitates weaning. Depending on the patient’s response to ventilation, however, sedation and neuromuscular blockade may be indicated. These interventions limit the patient’s capacity to cooperate fully with treatment. Breathing patterns imposed by the mode of mechanical ventilation influence venous return and aortic pressures8; thus mobilization needs to be prescribed accordingly. Furthermore, weaning patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and neuromuscular conditions is complicated by respiratory muscle weakness and fatigue (see Chapter 26), which may indicate respiratory muscle training or rest. Because of these challenges, weaning necessitates close cooperation and coordination within the team to maximize weaning success.

As for patients who are not critically ill, the assessment data are evaluated, problems and diagnoses made, and interventions prescribed based on the patient’s needs and goals. Physical therapy has a prominent role in the management of patients who are on mechanical ventilation.9,10 With each treatment, the responses are reviewed and prescription parameters of the interventions are refined to progress the patient

Restricted Mobility and Recumbency

Hospitalization, particularly in the ICU, is associated with a considerable reduction in mobility (i.e., loss of exercise stimulus) and recumbency (i.e., loss of gravitational stimulus) (see Chapters 18 and 20).11–13 These two factors are essential for normal oxygen transport; thus their removal has dire consequences for the patient with or without cardiovascular and pulmonary dysfunction.

In terms of a physiological hierarchy of treatment interventions (see Chapter 17), exploiting the physiological effects of acute mobilization, upright positioning, and their combination is the most physiologically justifiable primary intervention to maximize oxygen transport and prevent its impairment in patients who are critically ill.

Recumbency is nonphysiological; it is a position in which, all too often, most patients are injudiciously confined. Changing the position of the body from erect to supine positions results in significant physiological changes that may jeopardize the patient’s already compromised or threatened oxygen transport system (Box 33-2) (see Chapter 20).

Specificity of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Physical Therapy

Physical therapy interventions in the ICU (see Chapter 17 and Part III) are more specifically geared toward the status of each organ system, taking into consideration the pathophysiological basis for the patient’s signs and symptoms, the rationale for each intervention, and the physiological and scientific evidence supporting the effectiveness of the intervention.14 Physical therapy provides both prophylactic and therapeutic interventions for the patient in the ICU. Conservative, noninvasive measures constitute initial treatments of choice to avert or delay the need for additional invasive monitoring and treatment including supplemental oxygen, pharmacological agents, and the need for intubation and mechanical ventilation. The physical therapist aims to avoid, reduce, or postpone for as long as possible the need for respiratory support. Even if the patient is mechanically ventilated, maintaining some level of spontaneous breathing, no matter how minimal, is associated with improved oxygenation and outcomes.15 In addition, the physical therapist helps to prevent the multitude of side effects of restricted mobility and recumbency during bed rest. A summary of general information required before treatment of the patient in the ICU is presented in Box 33-3. This provides the basis for establishing a patient’s readiness to be mobilized and the progressive steps for doing so (Box 33-4 and Figure 33-2).

Maximizing Function

Maximizing function refers to maximizing the capacity to participate in one’s life roles and associated activities. This necessitates promotion of optimal physiological functioning at an organ system level, as well as promoting maximal functioning of the patient as a whole. In critical care, primary goals related to function optimization are initially focused on cardiovascular and pulmonary function. With improvement in oxygen transport, increased attention is given to optimal functioning of the patient with respect to self-care, self-positioning, sitting up, and walking. General physical therapy goals related to function optimization are shown in Box 33-5. Outcomes can be tracked objectively by recording the length of time a patient sits over the edge of the bed, sits in a chair at bedside, stands, and walks. Also, the weight a patient lifts as well as the number of repetitions and sets he or she performs can be readily quantified.

Prophylaxis

General aspects of patient care related to physical therapy practice include the role of prophylaxis or prevention. The complications of restricted mobility and recumbency are described in Chapter 18 and relate primarily to the status of the cardiovascular and pulmonary, neuromuscular, and musculoskeletal systems and overall functional capacity. In the ICU the negative physiological effects of restricted mobility are amplified in patients who are severely ill and older. A primary objective of the physical therapist therefore is to avoid or reduce these untoward effects on the patient’s recovery and the patient’s length of stay in the ICU. Ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) is the most common nosocomial infection in the ICU and is associated with poor outcomes and high cost of ICU care.

Preventive physical therapy goals include reducing the deleterious effects of restricted mobility and pathology on cardiovascular and pulmonary and neuromuscular function and reducing the risk of musculoskeletal deformity, neurological dysfunction, and decubitus ulcers over pressure areas (back of the head, shoulders, elbows, sacrum, and heels). Special mattresses or a special bed may be indicated. The negative sequelae of recumbency and restricted mobility, which can be life-threatening in people who are critically ill, are largely preventable. Particular care must be taken to avoid pressure sores because these increase the risk of infection and deterioration and can be life-threatening. Physical therapists as well as nurses need to pay particular attention to individuals at risk and to examine routinely for sites of redness, pressure, and potential skin lesions in every patient, regardless of expected length of stay in the ICU.16 The texture of bed covers, their smoothness, bunching of the bed gown, and irritation from lines and catheters to the patient must be routinely monitored. Prevention is key, given the potentially reduced immunity and capacity to heal of patients in the ICU.17 Although pressure sores are largely preventable, the need to be vigilant remains, given the deleterious consequences they may have on recovery. Unrelieved pressure and equipment failure have been identified as key causes of pressure sores in the patient after trauma.18 These causes of pressure sores are 100% avoidable with vigilance and monitoring. Physical therapists have a role for making recommendations about patient positioning between treatments in the interest of preventing deleterious sequelae of recumbency and restricted mobility.

Preparation for Treating the Patient in the Intensive Care Unit

Patients in the ICU are generally characterized by some degree of life-threatening medical instability or its risk. Before treating a given patient in the ICU, the physical therapist should be thoroughly familiar with the specific information shown in Box 33-6. Depending on the level of care in the ICU, nursing care is usually 1 : 1 or 1 : 2. Coordinating treatment with nursing interventions is efficient. It is helpful to have the nurse at hand to assist as required, particularly if the patient is beginning physical therapy. Alternatively, if the nursing care proved strenuous for the patient, physical therapy may be more beneficial if delayed.

General Clinical Aspects of the Management of the Intensive Care Unit Patient

Assessment and Evaluation

Although the priority in the ICU is survival, greater attention is now being placed on thriving after the episodes of care in the ICU and hospital (see Chapters 16 and 17). Therefore assessment and evaluation in the ICU focus on activity, participation, and quality of life as well as factors related to conventional oxygen transport deficits and multisystem function, in anticipation of the patient’s return to community living.

Monitoring

Maximizing the effects of physical therapy treatment depends on exploiting information from the ICU monitoring systems. Monitoring systems can be used to establish the indications and contraindications for treatment as well as parameters of the treatment prescription and progression, and to assess the patient. Physical therapy uses of monitoring systems in the ICU are summarized in Box 33-7. Physical therapists need to exploit the considerable amount of objective data available to them in patient management. A thorough knowledge and routine use of monitoring systems for each patient in the ICU cannot be overemphasized in terms of contributing to improved quality of care with less risk to the patient. Subjective responses of the patient are particularly important in the ICU, where the patient’s power and self-responsibility are compromised. Eliciting subjective responses can be achieved through a sign system, use of analog scales, and communication devices. The patient needs to be able to communicate basic needs if possible (e.g., discomfort or /pain, anxiety, fear, and general distress). Patients have been reported to experience significant levels of stress when being managed in the ICU—in turn, worsening outcomes.19

The monitoring systems described in Chapter 16 provide essential information with respect to the management of the patient in the ICU. Information regarding arousal, acid-base imbalance, and fluid and electrolyte balance helps to establish specific treatment goals. The Swan-Ganz catheter in situ permits measurement of pulmonary artery pressure and wedge pressure, which provide an index of myocardial sufficiency and specifically left-sided heart function. Central venous pressure gives an indication of fluid loading and the ability of the right side of the heart to cope with changes in circulating body fluids. Pressures related to heart function give the physical therapist an indication of pulmonary status and help to determine whether heart dysfunction is affecting lung function or lung dysfunction is affecting heart function, or both. Cardiovascular and pulmonary stress alerts the physical therapist to modify workloads or the physical demands of treatment to keep the patient medically stable and avoid undue fatigue and deterioration. The physical therapist conducts ongoing monitoring of the patient’s responses to invasive care in the ICU (e.g., responses to medication and fluid resuscitation, indications for intervention and refinement of its prescription) to ensure patient safety.

Pharmacological Agents

The physical therapist needs a thorough knowledge of the common pharmacological agents used in intensive care (see Chapter 45). With this knowledge, the physical therapist can augment the effects of these agents and optimize physical therapy treatment response when treatments are coordinated with medication schedules. Most medications have optimal dosages for any given patient, optimal sensitivity, and peak response time. Most medications have side effects. Side effects may cause deterioration in the patient’s condition, create apparent signs and symptoms suggestive of other disorders, or alter response to treatment. The physical therapist therefore needs to identify the medications each patient is taking and their side effects. Medication that contributes to suboptimal therapeutic outcomes warrants discussion with the team in terms of finding an alternative. One physical therapy outcome is the minimization of medication with effective physical therapy.

Treatment Prescription in the Intensive Care Unit

Physical therapy treatments in the ICU are judiciously selected in a goal-specific manner. As a general guideline, treatments descend in a physiological hierarchy (Chapter 17). Mobilization, exercise, and body positioning are exploited first with respect to their direct and potent effects on oxygen transport overall.20 Early mobilization and walking are priorities regardless of whether the patient is mechanically ventilated.21–23 At the other end of the treatment intervention hierarchy (i.e., least physiological interventions that have a more limited effect on the steps in the oxygen transport pathway overall) are conventional interventions such as airway clearance techniques and suctioning. Assessment of the oxygen uptake and delivery relationship is essential given the high metabolic demands of patients in the ICU24 and the documented associated exercise and stress responses associated with physical therapy.25

Supplemental Oxygen

Supplemental oxygen is usually administered continuously, whether the patient is ventilated or not, to maintain PaO2 level within an optimal range.26 Oxygen concentrations can be increased before treatment to help compensate for associated stress. Oxygen, however, should always be increased to 100% and inspired for at least 3 minutes before and after suctioning. Should arterial desaturation be apparent during treatment, oxygen may need to be increased. If the patient is spontaneously breathing without oxygen, supplemental oxygen may also be indicated during treatment to avoid desaturation. Oxygen administration is regulated by the ICU team based on arterial blood gas levels including arterial saturation and subjective distress. Severe hypoxemia is known to result in irreversible tissue damage within minutes, but hyperoxia can also produce harmful effects within hours. By maximizing alveolar ventilation, gas exchange, and ventilation and perfusion matching, supplemental oxygen can be optimally used and the effects of acidemia minimized.

Severe hypoxemia usually suppresses cardiac output to some degree. Cardiac output may be further compromised immediately after a patient has been placed on a mechanical ventilator because of impaired venous return resulting from the elevated transpulmonary pressure.27 An attempt is made to carefully balance ventilation with an optimal or adequate cardiac output by shortening inspiratory time and minimizing transpulmonary pressures by using lower tidal volumes.

Mucociliary Transport and Secretion Clearance

If the effects of mobilization on mucociliary transport and secretion accumulation have been exploited and further secretion clearance is warranted, postural drainage may be indicated. Postural drainage may be contraindicated in patients with unstable vital signs and is usually contraindicated immediately after feedings and meals. In some institutions, however, patients on continuous 24-hour tube feedings are tipped after feeding has been discontinued for 15 minutes. The cuff in the artificial airway is inflated to avoid aspiration. The specific postural drainage positions to be used are determined on the basis of the pathology, radiographs, and clinical examination. The recommended positions for the bronchopulmonary segments involved should be approximated as closely as possible (see Chapter 21) and modified as needed. Frequently, specific positioning in the ICU is compromised as a result of the patient’s status, intolerance to lying flat or being tipped, or limitations imposed by the monitoring apparatus or ventilator.

The role of manual techniques has long been questioned because they have been associated with desaturation, atelectasis, musculoskeletal trauma, discomfort, cardiac dysrhythmias, and cardiac arrest.28 Thus these techniques must be applied rationally, with appropriate monitoring, and modified accordingly. The precise sequence, duration, intensity, and frequency of treatment are based on treatment outcome rather than time. Oxygen demand has been shown to increase with manual airway techniques, and the hemodynamic and metabolic responses have been reported to resemble the response to exercise.24 The increases in cardiac output and blood pressure are thought to reflect increased sympathetic activity from stress as well as the exercise-like response.25 The stressful responses to ICU procedures as well as conventional airway clearance procedures have been reported to be effectively modulated with medication.29 A recent study reported no significant changes in  and mean arterial pressure with conventional airway clearance interventions compared with undisturbed side-lying positions.30 These discrepant findings may reflect differences in the intervention and subjects studied (stable patients who are ventilated). The application of manual techniques in the head-down position is contraindicated in patients with acute myocardial infarction and increased ICP. Relative contraindications include hemorrhage, bronchopulmonary fistula, acute chest trauma, lung abscess, and gastric reflux.31 Given the adverse effects of manual airway clearance interventions that have been reported, the physical therapist needs to ensure that more physiological alternatives associated with fewer risks have been exploited.

and mean arterial pressure with conventional airway clearance interventions compared with undisturbed side-lying positions.30 These discrepant findings may reflect differences in the intervention and subjects studied (stable patients who are ventilated). The application of manual techniques in the head-down position is contraindicated in patients with acute myocardial infarction and increased ICP. Relative contraindications include hemorrhage, bronchopulmonary fistula, acute chest trauma, lung abscess, and gastric reflux.31 Given the adverse effects of manual airway clearance interventions that have been reported, the physical therapist needs to ensure that more physiological alternatives associated with fewer risks have been exploited.

Bagging or Manual Hyperinflation

As soon as possible, spontaneous breathing is encouraged in conjunction with postural drainage. The small airways dilate slightly on inspiration and cause mucus to peel away from the walls; thus during expiration, mucus plugs are moved centrally toward the trachea. The degree to which chest wall percussion, shaking, and vibration facilitate this movement has remained equivocal in the literature.14,28 Thus these less substantiated, less physiological conventional procedures (i.e., manual techniques) should be considered carefully and only after other more supported and physiological treatments have been exploited. Furthermore, because of their documented hemodynamic and adverse effects,32 it is essential that the patient be continuously monitored for safety reasons and to establish a favorable treatment outcome. For the patient who is unconscious or paralyzed, the ventilator or self-inflating bag can be used to increase inflation volumes. Research is needed to examine the role of bagging in removal of mucus.

Weaning from the Mechanical Ventilator

Depending on the institution and country, the physical therapist, the respiratory therapist, or both are often responsible for assisting physicians in weaning the patient from mechanical ventilation. Coordinating goals and working with the ICU team to ensure that the weaning process is carried out expediently and with the least risk of weaning complications (e.g., postextubation atelectasis, aspiration, and hypoxemia) are priorities. Expediting weaning is an important ICU goal, as patient outcomes improve with shorter periods of mechanical ventilation.33 Evidence-based guidelines have been documented.

Weaning can increase cardiovascular and psychological stress, and in turn  . Patients at particular risk of weaning failure must be identified and monitored by the physical therapist during this process. One study reported that cardiovascular responses to weaning in patients after heart surgery depended on the type of surgery.34 Cardiac index, for example, was greater after abdominal aortic surgery than after bypass or transplantation surgery. Although the oxygen extraction ratio remained stable after aortic surgery, it increased somewhat after bypass surgery and markedly after transplantation surgery. Weaning patients with cardiac dysfunction from mechanical ventilation can lead to pulmonary edema because of increased venous return and release of catecholamines, reduced left ventricular compliance, compression of the heart by the lungs, and increased left ventricular afterload.

. Patients at particular risk of weaning failure must be identified and monitored by the physical therapist during this process. One study reported that cardiovascular responses to weaning in patients after heart surgery depended on the type of surgery.34 Cardiac index, for example, was greater after abdominal aortic surgery than after bypass or transplantation surgery. Although the oxygen extraction ratio remained stable after aortic surgery, it increased somewhat after bypass surgery and markedly after transplantation surgery. Weaning patients with cardiac dysfunction from mechanical ventilation can lead to pulmonary edema because of increased venous return and release of catecholamines, reduced left ventricular compliance, compression of the heart by the lungs, and increased left ventricular afterload.

Because of its profound effect on pulmonary function and gas exchange, body position must be optimized for weaning to maximize weaning success and avoid the need for reintubation because of weaning failure. Patients who are overweight warrant particular attention. Low tidal volume and high respiratory rates can jeopardize weaning success. In patients who are obese, a semirecumbent position may favor weaning, compared with a 90-degree upright position, which may cause the abdomen to encroach on the underside of the diaphragm and limit its excursion.35

Blood gas analysis and pulmonary function provide the indications for weaning. Ideally the patient’s spontaneous tidal volume should approximate that delivered by the ventilator. Forced vital capacity should be two to three times the patient’s required tidal volume. Weaning is not usually indicated if the patient requires positive end-expiratory pressure greater than 5 cm H2O or if FIO2 is greater than 0.4. In addition, patients who are unable to generate a negative inspiratory pressure of −20 mm Hg or greater are unlikely to be able to generate sufficient intrathoracic pressures for deep breathing and airway clearance and thus are poor candidates for weaning. Minute ventilation and maximum voluntary ventilation can be measured at bedside and contribute to the decision regarding whether to wean. Although weaning protocols differ depending on the patient and the ventilatory mode used, general guidelines for this common ICU procedure are outlined in Box 33-8.

Special Noninvasive Intensive Care Unit Priorities and Considerations

Intubation and mechanical ventilation are usually delayed as long as possible, particularly in individuals with COPD. These individuals have poor blood gas levels in combination with poor CO2 ventilatory drive. Once mechanically ventilated, the patient tends to deteriorate rapidly, and the risk of failure to wean is increased. Noninvasive mechanical ventilation (see Chapter 44) has been a more recent advance to provide low-risk ventilatory support as a means of avoiding associated risks of invasive ventilation. It is used for patients in whom short-term mechanical ventilation is anticipated.

Discharge from the Intensive Care Unit

The physical therapist is responsible for documenting the physical therapy treatment priorities and frequent progress notes during the ICU stay so that the team responsible for the patient after discharge can continue management with reduced risk of disruption of care or regression of the patient’s condition. The patient should be informed continually of his or her progress and the plans made by the team and family.36 The patient should be given as many choices as possible about his or her care and should be actively involved in long-term management planning.

Nonclinical Aspects of the Management of the Patient in the Intensive Care Unit

Teamwork

Comprehensive patient care in the ICU must include a multidisciplinary team. The ICU team usually includes non–health care professionals and health care professionals. The non–health care professionals include the patient, family or immediate support network, case manager, and possibly a spiritual or religious leader. The health care professionals typically include dieticians, nurses and nursing assistants, occupational therapists, physical therapists, physicians, respiratory therapists, social workers, and speech therapists. Teamwork is the essence of maximal patient care and must include the patient and family as much as possible, particularly in the ICU. The physical therapist interacts frequently with other team members, particularly the medical staff, nurses, and respiratory therapists if in the ICU, regarding observations and changes in the patient’s condition, medications, mechanical ventilation requirements, treatment goals, and treatment response (see Figure 33-2). In addition to providing therapy for patients and planning for discharge, the physical therapist is often consulted regarding early mobility, ambulation, body positioning, transferring, chair sitting, and self-care.

The Intensive Care Unit as a Healing Environment

The physical environment of the ICU has a profound effect on the patient’s recovery independent of the level of care received. Outside windows with daylight orient the patient to day and night. Other benefits include reduced number and types of complications and reduced length of stay in the ICU and in the hospital overall.37,38 Also, exposure to daylight may reduce the need for analgesia.39 Minimizing the sense of social isolation is important, so family is encouraged to be present as much as permitted by the ICU visiting policy. Pet therapy may have some role in the ICU, as it has been shown to have benefits in other care settings.40 Circadian rhythms are associated with fluctuations in physiological and hormonal functions important to the patient’s healing, recovery, and well-being, and these are compromised with bed rest deconditioning. Normalizing circadian rhythms can be achieved by optimizing a sleep schedule with more wakeful periods during the day and reduction of noise at night.41

End-of-Life Issues

Palliative care is provided to patients in the ICU with the goal of improving the quality of life of patients and their families facing life-threatening illness. Palliative care treatment focuses on the prevention, assessment, and treatment of pain and other symptoms, as well as the provision of psychological, spiritual, and emotional support. Anticipation of dying and death are traumatic for the patient, family and friends, and the health care team. The phases of dying42 that can be anticipated when caring for the patient who is at the end of life are presented in Box 33-9.

The psychosocial issues in conjunction with support of the patient’s physical status and comfort are priorities.43 Communicating effectively and being responsive to an individual’s dignity and needs are important. Each individual differs with respect to his or her needs, and time must be taken to identify these in an open and honest environment. Touching has a particularly important role in providing support and comfort as the end of life nears.

Principles of Physical Therapy Management

The family and friends of the patient who is dying have special needs that must be considered, and in fact constitute an integral part of the patient’s overall care. In general the physical comfort and personal hygiene of the patient, as well as the quality of the immediate psychosocial environment, are paramount concerns. Optimal functional capacity is maintained as much as possible44 and has been shown to improve even in patients whose course is unstable.45 Nonetheless, the individual’s priorities and needs may change quickly. The physical therapist needs to be flexible to accommodate these fluctuations and sensitive to indications for no intervention. This may be a time for providing support and touching, if the patient wishes. Compassion, understanding, and respect for the patient and the family must be forthcoming from the ICU team as a whole. The ability to be attentive, comforting, and compassionate is an invaluable personal quality that needs to be developed to a high degree in the critical care area. The team members need to attend to how the patient, if sufficiently alert, is dealing with the possibility of dying and must take their cues from the patient with respect to the role they need to play. If requested by the patient or family, spiritual care leaders are summoned.

and energy expenditure secondary to the increased work of breathing. Without adequate nutrition, patients incur the effects of deconditioning faster and are debilitated, less capable of responding optimally to therapy, and more susceptible to infection. Intravenous or external hyperalimentation is typically instituted early to maintain optimal nutritional status and avoid excessive physical wasting and deterioration. If a tracheostomy has been performed, the patient is able to eat normally, provided risk of aspiration is minimal.

and energy expenditure secondary to the increased work of breathing. Without adequate nutrition, patients incur the effects of deconditioning faster and are debilitated, less capable of responding optimally to therapy, and more susceptible to infection. Intravenous or external hyperalimentation is typically instituted early to maintain optimal nutritional status and avoid excessive physical wasting and deterioration. If a tracheostomy has been performed, the patient is able to eat normally, provided risk of aspiration is minimal.