CHAPTER 36 Complications of Wrist Arthroscopy

The use of arthroscopy has enabled direct visualization and diagnosis of intra-articular wrist pathology.1–3 It is widely used in the treatment of wrist injuries, such as triangular fibrocartilage complex tears, scapholunate and lunatotriquetral tears, and synovitis, and the excision of dorsal ganglia and débridement of arthritic lesions.4–10 Wrist arthroscopy has proved to be an excellent way to examine intra-articular pathology11–14 and to treat these pathologic conditions.15–27

PREVENTING COMPLICATIONS

Arthroscopy has justifiably been touted as a safe and effective method for examining the intra-articular components of the radiocarpal and midcarpal joints,28 and it is considered a relatively low-risk procedure.29–33 As with any surgical procedure, complications may be encountered, including tendon injury from inappropriately placed portals, skin slough from traction devices, nerve injury, complex regional pain syndrome,34–36 and rare conditions such as one case involving fistula formation after wrist arthroscopy.37 Associated with each portal are certain anatomic structures with which the surgeon must be familiar to prevent portal-specific complications from occurring.38 This chapter seeks to familiarize the wrist surgeon with these structures and techniques for preventing injury to them. Portal anatomy and the risks associated with each portal based on surrounding anatomic structures are addressed, along with the general risks associated with wrist arthroscopy. The Pearls and Pitfalls section describes common errors made when learning wrist arthroscopy and the techniques employed to avoid those errors.

RISKS AND COMPLICATIONS BY PORTAL SITE

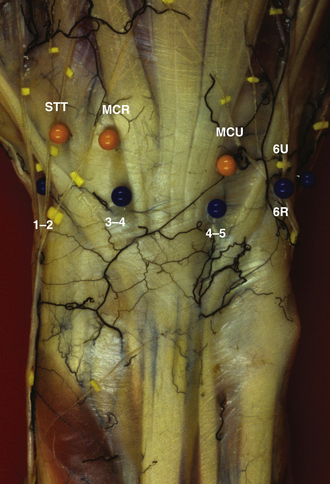

Wrist arthroscopy portals are based on the extensor compartments of the wrist. Figure 36-1 provides an overview of the dorsal arthroscopy portals with associated structures.

1-2 Portal

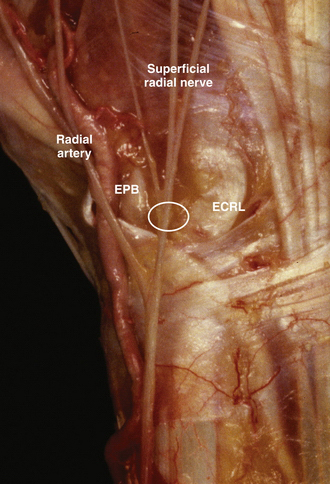

The superficial radial nerve is also at risk because its dorsal branch lies over the 1-2 portal. The most effective way to avoid laceration or traction of this nerve as the medial branch of the superficial radial nerve arborizes ulnarly is to make the portal skin incision with a no. 11 blade knife inserted only through the skin layer and then by traction on the skin itself, rather than using the blade, to enlarge the portal. Blunt dissection down to the capsule is recommended to ensure preservation of this dorsal branch as it crosses the portal site (Fig. 36-2).

3-4 Portal

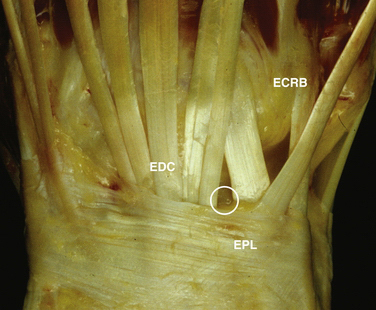

The 3-4 portal is most commonly the first portal established and is most easily established by inserting an 18-gauge needle into the wrist joint just distal to Lister’s tubercle and insufflating the joint with as much solution as the joint can hold comfortably. At that point, the needle and syringe may be removed from the joint while maintaining the capsular distention. The information from needle insertion and palpation of the capsular distention guides placement of the 3-4 portal directly over the radiocarpal joint between the ECRB/EPL and the EDC. The skin is pulled over the tip of the blade to establish the portal, lessening the risk of inadvertently lacerating one of the tendons. After the skin incision is made, the blunt trocar and cannula are inserted, moving the tip in a medial and lateral direction to have tactile feedback and ensuring guidance into the joint without injury to the articular cartilage (Fig. 36-3).

4-5 Portal

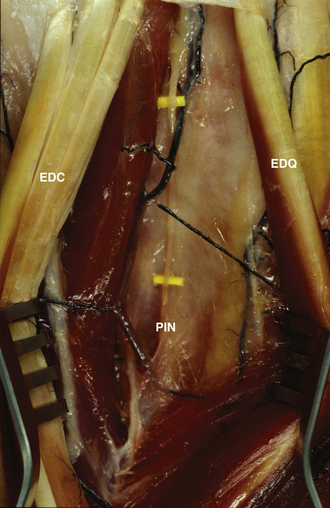

The structures most at risk during placement of the 4-5 portal (i.e., extensor digitorum communis–extensor digiti quinti [EDC-EDQ] portal) are the terminal branch of the posterior interosseous nerve and the dorsal sensory branch of the ulnar nerve. The posterior interosseous nerve passes deep to the fourth dorsal compartment on the ulnar side dorsal to the wrist to provide sensation to the wrist joint. The risk of damage to this nerve during placement of the 4-5 portal is lessened by placement of the portal in a slightly ulnar position with relation to the EDC tendon. The portal should be placed just radial to the EDQ tendon. From a practical point of view, the loss of the function of this nerve causes no functional deficit, and some think that it diminishes pain in the wrist joint.

The transverse branch of the ulnar dorsal sensory nerve is also at risk during placement of this portal. The transverse branch of this nerve passes distal to the portal, and risk of injury may be lessened by placing the portal as proximal as possible in the wrist joint. We recommend longitudinal portal placement followed by blunt insertion into the joint to ensure preservation of the nerve (Fig. 36-4).

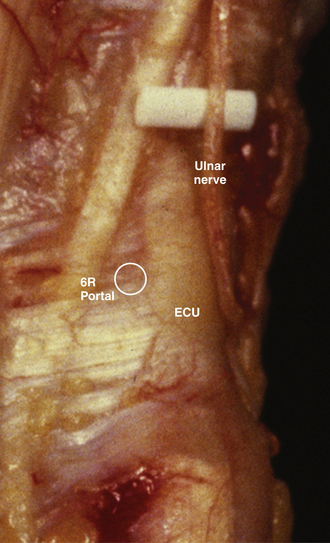

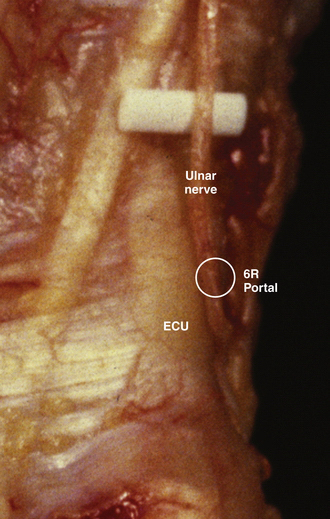

6-R Portal

The structures at most risk during placement of the 6-R portal (i.e., radial to the extensor carpi ulnaris [ECU] tendon) are the extensor tendons and branches of the dorsal sensory branch of the ulnar nerve. This nerve passes ulnar to the portal, and we stress portal placement on the radial side of the ECU tendon with blunt dissection to the joint, thereby preventing damage to this superficial nerve. We recommend making the skin incision in a longitudinal fashion with careful dissection down to capsule, at which point the trocar may be safely placed bluntly on the radial side of the ECU tendon (Fig. 36-5).

6-U Portal

The structure at most risk during placement of the 6-U portal (i.e., ulnar to the ECU tendon) is the main dorsal sensory branch of the ulnar nerve. We do not recommend the use of this portal unless there is no other alternative. This nerve passes over the portal, and we stress portal placement with blunt dissection to the joint, thereby preventing damage to this superficial nerve. We recommend making the skin incision and then carefully dissecting down to capsule to ensure that the nerve is not lacerated or entrapped during portal placement. After the nerve has been protected, the trocar may be placed bluntly on the ulnar side of the ECU tendon (Fig. 36-6).

Midcarpal Radial Portal

The structures most at risk in the midcarpal radial (MCR) portal (i.e., 1 cm distal to the 3-4 portal and in line with the radial border of the long metacarpal) are the extensor tendons (Fig. 36-7) and the articular cartilage. The space available for portal placement is smaller in the MCR portal compared with the midcarpal ulnar (MCU) portal (Fig. 36-8). For smaller patients, we recommend the use of a 1.8-mm arthroscope in all of the portals of the midcarpal joint because of the small potential space.

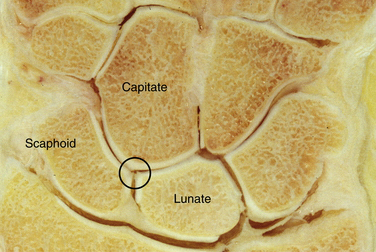

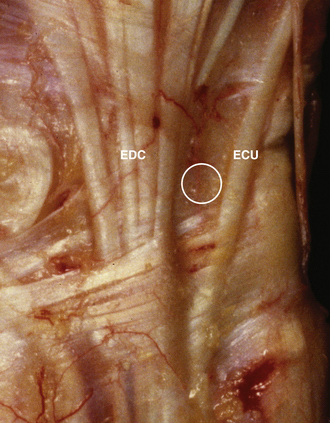

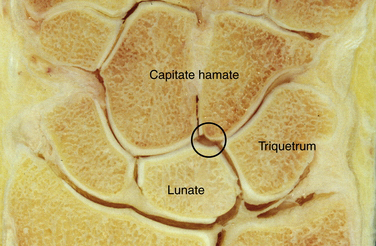

Midcarpal Ulnar Portal

The structures most at risk in the MCU portal (i.e., 1 cm distal to the 4-5 radiocarpal portal and in line with the axis of the ring metacarpal) are the extensor tendons (Fig. 36-9) and the articular cartilage. This portal has more room than the MCR portal, especially in patients who have a significant hamate facet of the lunate (Fig. 36-10).

Scaphotrapeziotrapezoid Portal

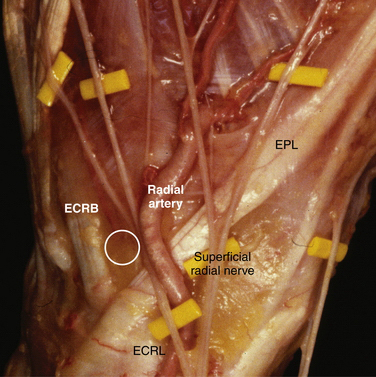

The structures most at risk with placement and use of the scaphotrapeziotrapezoid (STT) portal (i.e., EDC-EPL distal portal) are the radial artery and superficial radial nerve. The radial artery passes deep to the extensors through the anatomic snuffbox to lie between the two heads of the first dorsal interosseous muscle, and it is therefore directly at risk during placement of this portal (Fig. 36-11). The easiest way to avoid damage to the radial artery is to approach the space between the ECRL and the ECRB and ulnar to the EPL. This approach ensures that the artery and the radial nerve are palmar and radial to the portal.

FIGURE 36-11 The structures most at risk during placement and use of the scaphotrapeziotrapezoid (STT) portal are the radial artery and superficial radial nerve. It is safest if the STT portal is made on the radial border of the extensor carpi radialis brevis tendon.

(Photograph courtesy of Pau Galano, MD, Barcelona, Spain.)

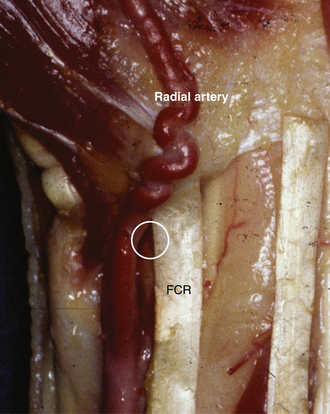

Palmar Portal

The palmar portal is the most precarious of all the portals discussed, because it lies between the radial artery, the median nerve, and the palmar cutaneous nerve (Fig. 36-12). Whether placed inside-out or outside-in, care must be taken to preserve the radial artery, which lies radial to the flexor carpi radialis (FCR) tendon; the palmar cutaneous nerve, which lies superficially between the FCR and palmaris longus tendons; and the median nerve, which lies deep to the palmaris longus and ulnar to the FCR. If placing the portal with an inside-out technique, the switching stick should be placed through the 3-4 portal between the radioscaphocapitate ligament and the long radiolunate ligaments with an incision radial to the FCR tendon on the volar aspect of the wrist. It is crucial to identify the radial artery and protect it during insertion of the cannula. If the outside-in technique is used with an incision made on the ulnar aspect of the FCR tendon, as described by Slutsky, care must be taken to protect the palmar cutaneous and median nerve proper.39

CONCLUSIONS

PEARLS& PITFALLS

PEARLS

PITFALLS

1. Geissler W, Walsh JJ. Wrist arthroscopy. Available at http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1241370-overview accessed August 2007

2. North ER, Thomas S. An anatomic guide for arthroscopic visualization of the wrist capsular ligaments. J Hand Surg Am. 1988;13:815-822.

3. Whipple TL, Marotta JJ, Powell JH. Techniques of wrist arthroscopy. Arthroscopy. 1986;2:244-252.

4. Bain GI, Munt J, Turner PC. New advances in wrist arthroscopy. Arthroscopy. 2008;24:355-367.

5. Beredjiklian PK, Bozentka DJ, Leung YL, Monaghan BA. Complications of wrist arthroscopy. J Hand Surg Am. 2004;29:406-411.

6. Bernstein MA, Nagle DJ, Martinez A, et al. A comparison of combined arthroscopic triangular fibrocartilage complex débridement and arthroscopic wafer distal ulna resection versus arthroscopic triangular fibrocartilage complex débridement and ulnar shortening osteotomy for ulnocarpal abutment syndrome. Arthroscopy. 2004;20:392-401.

7. Chloros GD, Wiesler ER, Poehling GG. Current concepts in wrist arthroscopy. Arthroscopy. 2008;24:343-354.

8. Chloros GD, Shen J, Mahirogullari M, Wiesler ER. Wrist arthroscopy. J Surg Orthop Adv. 2007;16:49-61.

9. McAdams TR, Hentz VR. Injury to the dorsal sensory branch of the ulnar nerve in the arthroscopic repair of ulnar-sided triangular fibrocartilage tears using an inside-out technique: a cadaver study. J Hand Surg Am. 2002;27:840-844.

10. Tsu-Hsin CE, Wei JD, Huang VW. Injury of the dorsal sensory branch of the ulnar nerve as a complication of arthroscopic repair of the triangular fibrocartilage. J Hand Surg Br. 2006;31:530-532.

11. Chung KC, Zimmerman NB, Travis MT. Wrist arthrography versus arthroscopy: a comparative study of 150 cases. J Hand Surg. 1996;21:591-594.

12. Cooney WP. Evaluation of chronic wrist pain by arthrography, arthroscopy, and arthrotomy. J Hand Surg Am. 1993;18:815-822.

13. Johnstone DJ, Thorogood S, Smith WH, Scott TD. A comparison of magnetic resonance imaging and arthroscopy in the investigation of chronic wrist pain. J Hand Surg Br. 1997;22:714-718.

14. Pederzini L, Luchetti R, Soragni O, et al. Evaluation of the triangular fibrocartilage complex tears by arthroscopy, arthrography, and magnetic resonance imaging. Arthroscopy. 1992;8:191-197.

15. Adolfsson L. Arthroscopic diagnosis of ligament lesions of the wrist. J Hand Surg Br. 1994;19:505-512.

16. Aviles AJ, Lee SK, Hausman MR. Arthroscopic reduction-association of the scapholunate. Arthroscopy. 2007;23:105.

17. Geissler WB. Arthroscopically assisted reduction of intra-articular fractures of the distal radius. Hand Clin. 1995;11:19-29.

18. Geissler WB, Freeland AE. Arthroscopically assisted reduction of intraarticular distal radial fractures. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1996;327:125-134.

19. Geissler WB. Arthroscopic excision of dorsal wrist ganglia. Tech Upper Extrem Surg. 1998;2:196-201.

20. Levy HJ, Glickel SZ. Arthroscopic assisted internal fixation of volar intraarticular wrist fractures. Arthroscopy. 1993;9:122-124.

21. Osterman AL. Arthroscopic débridement of triangular fibrocartilage complex tears. Arthroscopy. 1990;6:120-124.

22. Osterman AL, Raphael J. Arthroscopic resection of dorsal ganglion of the wrist. Hand Clin. 1995;11:7-12.

23. Osterman AL, Seidman GD. The role of arthroscopy in the treatment of lunatotriquetral ligament injuries. Hand Clin. 1995;11:41-50.

24. Slade JF3rd, Gutow AP, Geissler WB. Percutaneous internal fixation of scaphoid fractures via an arthroscopically assisted dorsal approach. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002;84(suppl 2):21-36.

25. Whipple TL. The role of arthroscopy in the treatment of intra-articular wrist fractures. Hand Clin. 1995;11:13-18.

26. Whipple TL. The role of arthroscopy in the treatment of scapholunate instability. Hand Clin. 1995;11:37-40.

27. Wolfe SW, Easterling KJ, Yoo HH. Arthroscopic-assisted reduction of distal radius fractures. Arthroscopy. 1995;11:706-714.

28. Viegas SF. Midcarpal arthroscopy: anatomy and portals. Hand Clin. 1994;10:577-587.

29. Bettinger PC, Cooney WP, Berger RA. Arthroscopic anatomy of the wrist. Orthop Clin North Am. 1995;26:707-719.

30. Botte MJ, Cooney WP, Linscheid RL. Arthroscopy of the wrist: anatomy and technique. J Hand Surg Am. 1989;14(2 pt. 1): 313-316.

31. Buterbaugh GA. Radiocarpal arthroscopy portals and normal anatomy. Hand Clin. 1994;10:567-576.

32. Ekman EF, Poehling GG. Principles of arthroscopy and wrist arthroscopy equipment. Hand Clin. 1994;10:557-566.

33. Roth JH, Poehling GG, Whipple TL. Hand instrumentation for small joint arthroscopy. Arthroscopy. 1988;4:126-128.

34. Culp RW. Complications of wrist arthroscopy. Hand Clin. 1999;15:529-535.

35. DelPinal F, Herrero F, Cruz-Camara A, San Jose J. Complete avulsion of the distal posterior interosseous nerve during wrist arthroscopy: a possible cause of persistent pain after arthroscopy. J Hand Surg Am. 1999;24:240-242.

36. DeSmet L. Pitfalls in wrist arthroscopy. Acta Orthop Belg. 2002;68:325-329.

37. Shirley DSL, Mullet H, Stanley JK. Extensor tendon sheath fistula formation as a complication of wrist arthroscopy. Arthroscopy. 2008;24:1311-1312.

38. Yu HL, Chase RA, Strauch B. Atlas of Hand Anatomy and Clinical Implications. St. Louis, MO: Mosby; 2004.

39. Slutsky DJ. Wrist arthroscopy through a volar radial portal. Arthroscopy. 2002;18:624-630.