26 Complications of temporary fillers

Summary and Key Features

• Soft tissue augmentation with temporary fillers continues to be among the most commonly performed cosmetic procedures

• There are a variety of temporary dermal fillers with an ever-increasing number coming to market. As more fillers become available, it is imperative that the aesthetic physician who injects dermal fillers has proper training in their use and understands the differences between them

• Though generally safe, complications can occur with temporary fillers; physicians need to recognize and manage these complications when they present

• Peri-procedural adverse events such as bruising, swelling, and pain are extremely common and usually resolve in less than 7 days

• Proper injection technique is crucial to minimize visible and / or symptomatic papules and nodules

• To minimize the risk of infection and biofilm formation, one should consider a skin preparation utilizing chlorhexidine and / or isopropyl alcohol

• The cause of granulomatous reaction is multifactorial and may be due to a true foreign-body reaction to the particulate or gelatinous filler or to the emergence of a biofilm

• Early institution of antibiotics, often for a prolonged period, is vital when a patient presents with inflammatory papules and nodules

• Early recognition of impending necrosis after injection is critical; treatment with hyaluronidase, topical nitroglycerin, and massage may be required

• Judicious use of injectables requires an appreciation of normal facial anatomy and the changes that occur with the aging process

• There is an alarming trend of increasing numbers of non-aesthetic physicians and non-MDs using these products; one may expect to see potential complications in the office

Introduction

Materials approved for soft tissue augmentation can be divided into biodegradable, semibiodegradable, and non-biodegradable products. These classifications correlate with their duration of effect as being temporary (approximately 6–12 months), temporary-plus (duration up to 18 months), or permanent (Box 26.1). As more fillers become available, it is imperative to understand the differences between them, the complications that can occur from each, and how best to avoid and treat them when they do occur.

Potential complications associated with temporary soft tissue fillers can be categorized by the time of onset (Box 26.2). In general, adverse events can be subdivided into acute and delayed reactions. Acute reactions are procedural or related to injection technique. They are usually transient and are manifested by erythema, edema, ecchymosis, pruritus, and pain in the first week after injection. Delayed reactions are related to the product itself, or the interaction between the filler and the host response. They are usually manifested by persistent erythema, swelling, nodules, and indurations developing months to years after. The nature of these reactions and their treatment will be summarized in this chapter.

Injection site reactions

The most common adverse events associated with fillers are local injection site reactions, manifested by pain, erythema, and edema. They are typically mild, localized, and transient, resolving within 4–7 days. A recent study by Brandt et al evaluating the efficacy and safety of biphasic hyaluronic acid Restylane® and Perlane® in the lower face revealed that the majority of patients treated with both small and large gel-particle hyaluronic acid experienced at least one injection site reaction. The reported events in decreasing order of occurrence consisted of bruising, tenderness, swelling, and redness. In another study comparing hyaluronic acid (Restylane®) with collagen (Zyplast®) for the treatment of nasolabial folds in contralateral sides, injection site reactions occurred at 93.5% and 90.6% of the hyaluronic acid and collagen treated sites, respectively. The bruising can be severe, especially in patients who have taken antiplatelet agents such as aspirin or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agents, as shown in Figure 26.1.

Edema and ecchymosis

Some of the most common post-procedure adverse events are bruising and swelling secondary to local trauma from the injection (Fig. 26.1). Reviewing all medications and supplements with the patient can minimize the degree of edema and ecchymosis. Avoidance of agents that inhibit coagulation is recommended, including aspirin (unless taking for ‘therapeutic’ indications) and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medications, as well as supplements such as garlic and Ginkgo biloba that have an inhibitory effect on platelets. Other supplements such as vitamin E, fish oil, glucosamine, ginger, ginseng, green tea, and celery root can inhibit coagulation pathways and further increase bleeding and bruising. It is recommended to withhold these supplements at least 5 days prior to treatment.

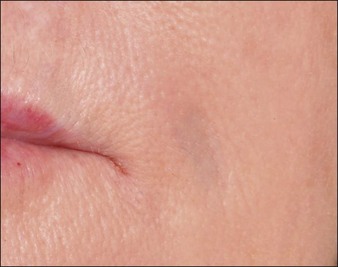

Nodules and papules

Inappropriate placement of fillers may result in the development of subcutaneous nodules and papules. The majority of these are manifested as palpable and / or visible bumps under the skin. Injecting too superficially can lead to lumps of visible product, or bluish bumps under the skin explained by the Tyndall effect with hyaluronic acid fillers (Fig. 26.2). Such reactions can, for the most part, be prevented by use of correct technique. Treatment of visible papules can often be accomplished by firm digital pressure, by aspiration, or by incision and drainage. When persistent papules and nodules are due to the use of a hyaluronic acid filler, the enzyme hyaluronidase can be utilized to treat them.

In the past few years, Narins and others have recommended changes in the protocol for product reconstitution, dilution, and administration that have helped limit this potential complication. PLLA should be reconstituted approximately 24–48 hours prior to injection with approximately 7–8 mL of bacteriostatic water, with 1 mL of lidocaine added at the time of injection. Product placement in the appropriate deep injection planes will help minimize nodules. Figure 26.3 shows a visible periocular papule following too-superficial placement of PLLA using an older dilution technique. For injection of the cheek, preauricular area, nasolabial folds, and lower face, injection should be into the deeper subcutaneous plane. For treatment of the temples, PLLA should be injected beneath the temporalis fascia, and for injection of the zygoma, maxilla, and mandibular regions, depot injection in the subperiosteal plane is desired. Care should be taken not to inject the precipitate at the end of the syringe. Following implantation, vigorous massage of the treatment area with instructions for the patient to massage at home is recommended. The post-treatment ‘rule of 5s’ is easy for the patients to remember: massage 5 times per day, for 5 minutes, for 5 days.

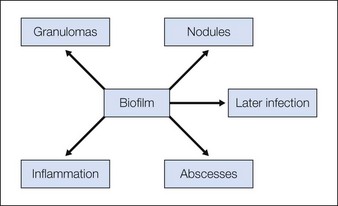

Biofilms

Biofilm reactions have been reported more frequently when a permanent non-degradable gel such as silicone or polyacrylamide gel is injected: however, they can occur with the use of temporary filler agents as well. Following filler injections, there may be both acute and delayed onset of erythematous papules and nodules. Some of these reactions have been reported years after injection of the product. Often culture of these lesions will lead to negative results as standard culturing techniques are not sensitive enough to detect these types of infections, leading some to incorrectly refer to them as ‘sterile abscesses’. It is important to understand how a biofilm can be responsible for many filler side effects, particularly those that present as early- or late-onset ‘angry red bumps’. Biofilms can result in a clinical picture of an inflammatory response, a local infection including an abscess or cellulitis, a systemic infection with sepsis, a granulomatous response with a foreign-body granuloma, or a nodule (Fig. 26.4). It has been noted that subsequent trauma or injection at sites of previous filler placement can activate biofilms with the possible induction of a ‘granulomatous or an infectious response’.

Any inflammatory nodule should first be treated as an infection. The first treatment of choice for most papules and nodules, whether they are red and / or painful, should be an antibiotic such as clarithromycin for 2–6 weeks, in lieu of initial treatment with intralesional corticosteroid injections. If these lesions are treated initially with steroids, intralesionally or systemically, it can make the inflammation much worse by further activating the biofilm and prolonging the infectious process. Intralesional steroid injections should be used only if the patient is already taking an antibiotic. If the substance injected is a long-lasting particulate filler, excision must be considered if antibiotics and steroids are not successful (Box 26.3).

Box 26.3

Algorithm for the treatment of inflammatory nodules

Incision and drainage to expel as much of the substance as possible

Incision and drainage to expel as much of the substance as possible

Oral antibiotics for at least 2–6 weeks. May need multiple agents if no response, or intravenous antibiotics if severe

Oral antibiotics for at least 2–6 weeks. May need multiple agents if no response, or intravenous antibiotics if severe

Avoid initial use of intralesional steroids. Use only if the patient is already on an antibiotic regimen

Avoid initial use of intralesional steroids. Use only if the patient is already on an antibiotic regimen

Inject hyaluronidase if caused by hyaluronic acid-based filler

Inject hyaluronidase if caused by hyaluronic acid-based filler

Excision or debridement of the nodule if no response and long-term persistence

Excision or debridement of the nodule if no response and long-term persistence

Alam M, Dover JS. Management of complications and sequelae with temporary injectable fillers. Plastic Reconstructive Surgery. 2007;120:S98–S105.

Brandt F, Bassichis B, Bassichis M, et al. Safety and effectiveness of small and large gel-particle hyaluronic acid in the correction of perioral wrinkles. Drugs in Dermatology. 2011;10:982–987.

Christensen L. Normal and pathologic tissue reactions to soft tissue gel fillers. Dermatologic Surgery. 2007;33(suppl 2):S168–S175.

Christensen L. Host tissue interaction, fate, and risks of degradable and nondegradable gel fillers. Dermatologic Surgery. 2009;35(suppl 2):S1612–S1619.

Cohen JL. Understanding, avoiding, and managing dermal filler complications. Dermatologic Surgery. 2008;34(suppl 1):92–99.

Dayan SH, Arkins JP, Brindise R. Soft tissue fillers and biofilms. Facial Plastic Surgery. 2011;27(1):23–28.

Dover JS, Rubin MG, Bhatia AC. Review of the efficacy, durability, and safety data of two nonanimal stabilized hyaluronic acid fillers from a prospective, randomized, comparative, multicenter study. Dermatologic Sugery. 2009;35(suppl 1):S322–S331.

Glashofer MG, Cohen JL. Complications from soft-tissue augmentation of the face: A guide to understanding, avoiding, and managing periprocedural issues. In: Jones D, ed. Injectable fillers, principles and practice. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell; 2010:121–139.

Grunebaum LD, Allemann I, Dayan S, et al. The risk of alar necrosis associated with dermal filler injection. Dermatologic Surgery. 2009;35(suppl 2):S1635–S1640.

Hamilton RG, Strobos J, Adkinson NF. Immunogenicity studies of cosmetically administered nonanimal-stabilized hyaluronic acid particles. Dermatologic Surgery. 2007;33(suppl 2):S176–S185.

Hamilton DG, Gauthier N, Robertson BF. Late-onset, recurrent facial nodules associated with injection of poly-L-lactic acid. Dermatologic Surgery. 2008;34:123–126.

Hirsch RJ, Cohen JL. Surgical insights: challenge: correcting superficially placed hyaluronic acid. Skin and Aging. 2007;15:36–38.

Hirsch RJ, Cohen JL, Carruthers JD. Successful management of an unusual presentation of impending necrosis following a hyaluronic acid injection embolus and a proposed algorithm for management with hyaluronidase. Dermatologic Surgery. 2007;33:357–360.

Lemperle G, Rullan PP, Gauthier-Hazan N. Avoiding and treating dermal filler complications. Plastic Reconstructive Surgery. 2006;118(suppl 3):S92–S107.

Leonhardt JM, Lawrence N, Narins RS. Angioedema acute hypersensitivity reaction to injectable hyaluronic acid. Dermatologic Surgery. 2005;31:577–579.

Lowe NJ, Maxwell CA, Patnaik R. Adverse reactions to dermal fillers: review. Dermatologic Surgery. 2005;31:1626–1633.

Monheit GD, Rohrich RJ. The nature of long-term fillers and the risk of complications. Dermatologic Surgery. 2009;35(suppl 2):S1598–S1604.

Narins RS. Minimizing adverse events associated with poly-l-lactic acid injection. Dermatologic Surgery. 2008;34(suppl 1):S100–S104.

Narins RS, Jewell M, Rubin M, et al. Clinical conference: management of rare events following dermal fillers – focal necrosis and angry red bumps. Dermatologic Surgery. 2006;32:426–434.

Narins RS, Coleman WP, Glogau RG. Recommendations and treatment options for nodules and other filler complications. Dermatologic Surgery. 2009;35:1667–1671.

Percival SL, Emanuel C, Cutting KF, et al. Microbiology of the skin and the role of biofilms in infection. International Wound Journal. 2011;9(1):14–32.

Requena L, Requena C, Christensen L, et al. Adverse reactions to injectable soft tissue fillers. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2011;64:1–34.

Resko AE, Sadick NS, Magro CM, et al. Late-onset subcutaneous nodules after poly-l-lactic acid injection. Dermatologic Surgery. 2009;35:380–384.

inch (12 mm) of 2% nitroglycerin paste should be massaged onto the affected area, which will often result in revascularization as manifested by a pink hue within a few minutes. Skin testing with hyaluronidase should be performed, and if no hypersensitivity to this agent is seen then 10–30 units diluted in a 1 : 1 ratio with saline should be injected per 2 × 2 cm2 area into the region of impending necrosis. Hyaluronidase has been shown to reduce edema, which could minimize occluding vessel pressure. Therefore hyaluronidase is of benefit in the management of impending necrosis even if not utilizing a hyaluronic-based filler. In more severe or unresponsive cases of necrosis, Schanz and colleagues described their success using deep subcutaneous injections of low-molecular-weight heparin into the affected area.

inch (12 mm) of 2% nitroglycerin paste should be massaged onto the affected area, which will often result in revascularization as manifested by a pink hue within a few minutes. Skin testing with hyaluronidase should be performed, and if no hypersensitivity to this agent is seen then 10–30 units diluted in a 1 : 1 ratio with saline should be injected per 2 × 2 cm2 area into the region of impending necrosis. Hyaluronidase has been shown to reduce edema, which could minimize occluding vessel pressure. Therefore hyaluronidase is of benefit in the management of impending necrosis even if not utilizing a hyaluronic-based filler. In more severe or unresponsive cases of necrosis, Schanz and colleagues described their success using deep subcutaneous injections of low-molecular-weight heparin into the affected area.