CHAPTER 140 Complications of Temporal Bone Infections

Epidemiology

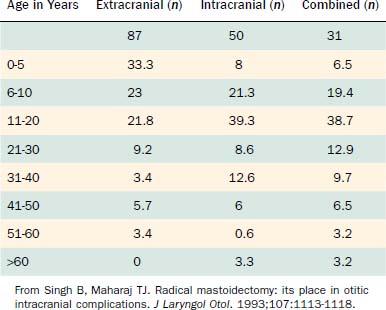

Table 140-1 presents the age distribution of extracranial, intracranial, and combined complications in a large series of patients. Nearly 80% of extracranial complications and 70% of intracranial complications occurred in children in the first 2 decades of life. Extracranial complications, led by postauricular abscess, most commonly occurred in children younger than 6 years.1 In a series of 93 intracranial and extracranial complications of otitis media, 58% were present in patients younger than 20 years.2 Low socioeconomic status and overcrowding confer either greater risk of or diminished resistance to an infection with an extended course and complications. Associations with inadequate health education and limited access to medical care likely contribute to heightened risk of complication. For this reason, most of the current reports of otogenic brain abscesses come from underdeveloped countries. Although the number of cases with immunodeficiency has increased, large series of patients with complications of otitis media have not been reported in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection or acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, or in patients receiving immunosuppressive therapy after organ transplantation, even though such individuals do have heightened risks of suppurative ear disease.

Table 140-1 Age Distribution of 268 Patients with Complications of Otitis Media between January 1985 and December 1990

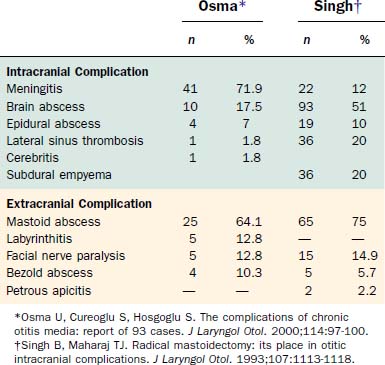

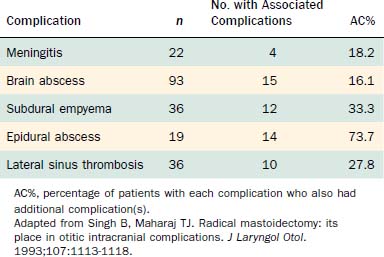

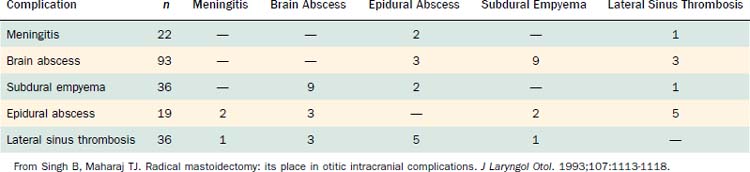

Table 140-2 shows the classification of extracranial and intracranial complications, and Table 140-3 summarizes the relative frequencies of those complications. The dominant extracranial complication is postauricular abscess, and the dominant intracranial complication is meningitis. Complications tend to occur multiply, especially intracranial complications, as shown in Tables 140-4 and 140-5. Although all of the complications originate from infection in the pneumatized spaces of the middle ear and mastoid, the mechanisms by which complications occur in AOM differ from the mechanisms associated with COM. We discuss these two entities separately.

Table 140-2 Classification of Complications of Acute and Chronic Otitis Media

| Extracranial | Intracranial |

|---|---|

| Acute mastoiditis | Meningitis |

| Coalescent mastoiditis | Brain abscess |

| Chronic mastoiditis | Subdural empyema |

| Masked mastoiditis | Epidural abscess |

| Postauricular abscess | Lateral sinus thrombosis |

| Bezold abscess | Otitic hydrocephalus |

| Temporal abscess | |

| Petrous apicitis | |

| Labyrinthine fistula | |

| Facial nerve paralysis | |

| Acute suppurative labyrinthitis | |

| Encephalocele and cerebrospinal fluid leakage |

From Harker LA. Cranial and intracranial complications of acute and chronic otitis media. In: Snow JB, Ballenger JJ, eds: Ballenger’s Otorhinolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery. 16th ed. Hamilton, Ontario: Decker; 2003.

Acute Otitis Media

An estimated 85% of all children experience at least one episode of AOM, making it the most common bacterial infection of childhood.3 Predisposing factors include young age; male sex; receiving bottle feedings; and being exposed to a daycare environment, crowded living conditions, or smoking within the home. Medical conditions such as cleft palate; Down syndrome; and mucous membrane abnormalities such as cystic fibrosis, ciliary dyskinesia, and immunodeficiency states also predispose individuals to otitis media.

After the first few weeks of life, acute suppurative otitis media is caused primarily by three organisms: Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, and Branhamella catarrhalis, composing roughly 30%, 20%, and 10% of isolates.3 Optimal treatment for acute suppurative otitis media with complications includes appropriate antibiotics in addition to myringotomy and placement of a ventilating tube. Tympanocentesis is used primarily to obtain material for culture and sensitivity to identify the offending organism, but it can also reduce the bacterial population. Myringotomy and tube placement also provide material to identify the involved organism. After treatment, the physician should document that the AOM has completely resolved by tympanometry and otoscopy if the tympanic membrane is intact, and by otoscopy if a ventilating tube is in place. If the complication was intracranial, a computed tomography (CT) scan or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) study should be obtained.

Chronic Otitis Media

COM changes are accompanied by a characteristic bacteriology compared with acute conditions. Harker and Koontz4 cultured 30 cholesteatomas at surgery and isolated at least one anaerobic organism in 67% of the cases, at least one aerobic organism in 70%, and both organisms in 50%. In 57% of the cholesteatomas, multiple organisms were cultured; in 30%, five or more bacteria were identified. Even without clinical infection, anaerobes, such as Propionibacterium acnes, were frequently isolated. An ear with COM is highly likely to harbor multiple bacteria of anaerobic and aerobic types.

Diagnosis

History

Intracranial complications, most notably meningitis, intraparenchymal brain abscess, and subdural empyema, can alter the patient’s level of consciousness. Of patients in the study by Singh and Maharaj,1 15% were drowsy on admission, 18% were stuporous, and 2% presented in a comatose state. Establishing the chronology of this alteration of sensorium helps the physician differentiate among diagnoses of brain abscess, meningitis, and subdural empyema. A brain abscess takes weeks to develop, whereas it takes only a few hours to several days for meningitis and subdural empyema to become fulminant and progress to coma.

Imaging Techniques

CT scanning is essential for all patients suspected to have complications of otitis media. CT is a fast and reliable method for assessing the status of the middle ear and the mastoid air cell system and diagnosing intracranial complications of otitis media.5,6 CT reveals bony details of the middle ear, epitympanic, and mastoid structures, and documents pneumatization versus opacification by inflammatory process. CT can show progressive demineralization and loss of the bony septa of air cells in coalescent mastoiditis, and reveal erosion of the bony plates covering the sigmoid sinus, cerebellum, or tegmen of the middle ear, mastoid, and bony labyrinth itself.

Treatment

A mastoidectomy under these circumstances is hampered by inflammation, and landmarks can be obscured. When no cholesteatoma is associated with the mastoiditis, the external auditory canal wall can be left intact unless visibility is inadequate. An open cavity, canal wall down procedure is preferred in the presence of cholesteatoma.1

Extracranial (Intratemporal) Complications

Acute Mastoiditis

Acute mastoiditis can develop when AOM fails to resolve. According to Luntz and colleagues,7 acute mastoiditis exists when there are signs of AOM on otoscopy and local inflammatory findings over the mastoid process (e.g., pain, erythema, tenderness, auricular protrusion), or when the mastoid inflammatory changes coexist with radiographic or surgical findings of mastoiditis with or without evidence of AOM. Other authors insist on the concomitant presence of AOM, mastoid physical findings, and radiologic findings.8

Luntz and colleagues7 reported results of a multicenter retrospective study of 223 such patients that provided valuable insight into the process. Of patients, 28% were younger than 1 year at diagnosis, 38% were 1 to 4 years old, and 21% were 4 to 8 years old. Although one third of patients experienced signs and symptoms of AOM immediately preceding the mastoiditis, two thirds did not. Thirty percent of the patients had a history of recurrent AOM, and 5% (all of whom had recurrent AOM) had a prior episode of acute mastoiditis.

One third of the patients exhibited symptoms for 48 hours or less before diagnosis, and another third had symptoms for 2 to 6 days before presenting with acute mastoiditis. Spontaneous tympanic membrane perforation occurred in less than one fourth of patients; the tympanic membrane was bulging or erythematous in two thirds. Twenty-two percent of the patients presented with complications on admission, the most common of which was subperiosteal abscess (Fig. 140-1), followed by meningoencephalitis and occasional cases of other complications.

Bak-Pedersen and Ostri9 reviewed the records of 79 patients who underwent acute cortical mastoidectomy for acute mastoiditis. All patients had erythema and swelling and pain over the mastoid associated with a current or recent episode of AOM that did not improve after 24 to 48 hours of intravenous antibiotics. The average age in the series was 16 months, and the average duration from the onset of disease (AOM) until admission for acute mastoiditis was 9 days. Only one third of the patients exhibited an asymptomatic interval between AOM symptoms and the mastoiditis.

Van Zuijlen and colleagues10 pointed out that in countries such as the Netherlands, where it is unusual to prescribe antibiotics as first-line treatment for AOM, the incidence of acute mastoiditis is considerably higher than in countries where antibiotics are routinely prescribed for AOM. Lower overall costs and reduced incidence of allergic reactions resulting from withholding antibiotics in routine AOM must be weighed against heightened risks of mastoiditis and other complications.

Coalescent Mastoiditis

Pathology

Initially, hyperemia and edema of the mucoperiosteal lining of the mastoid air cells block the narrow aditus and disrupt aeration. The mucous membrane thickens, and impaired ciliary function prevents normal middle ear drainage through the eustachian tube. The serous exudate becomes purulent as inflammatory cells accumulate. Continued inflammation, hyperemia, and accumulation of purulent debris result in venous stasis, localized acidosis, and decalcification of the bony septa. The osteoclastic activity in the inflamed periosteum softens and decalcifies the bony partitions, causing the small air cells to coalesce into a larger cavity.11

Pathophysiology

As the infection grows, elevated pressure within the mastoid may extend the infection beyond the confines of the mastoid. In the presence of intense inflammation and infection, phlebitis and periphlebitis are common and spread the infection to the adjacent meninges, sigmoid sinus, cerebellum, and temporal lobe.12 Infection may extend to the meninges, sigmoid sinus, labyrinth, or facial nerve. The most common pathway for infection to extend beyond the mastoid is through the lateral cortex behind the ear. Less commonly, it can extend to the soft tissues in the upper portion of the neck (see section on Bezold’s abscess) and, rarely, to the soft tissue anterior and superior to the auricle either by direct extension through eroded bone or by phlebitis and periphlebitis. Go and coworkers13 found only 8 of 118 patients in whom the mastoiditis had caused an intracranial complication.

Diagnosis

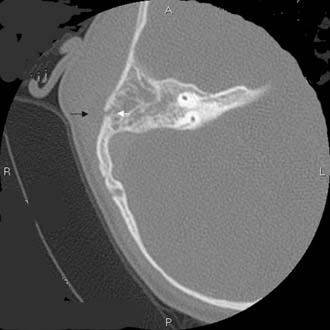

The clinician should order a complete blood count and hematologic studies followed by CT scanning, which can establish the diagnosis by documenting the breakdown of the bony cell walls and opacification of the pneumatized spaces (Figs. 140-2 and 140-3). If any suggestion of an intracranial complication exists, the clinician should obtain an enhanced MRI scan.

Chronic Mastoiditis

Etiology

Chronic mastoiditis can occur in association with a long-standing tympanic membrane perforation, with cholesteatoma, or as a complication from an infection after placement of a middle ear ventilating tube. As noted previously, ventilating tube mastoiditis tends to occur in young children who have experienced water contamination and have undergone cultures and treatment with multiple antibiotic drops and oral antibiotics. Mastoiditis with tympanic membrane perforation occurs when an episode of AOM with perforation pursues a course of chronic infection, rather than resolving or developing into coalescent mastoiditis. Chronic mastoiditis of this type can also begin when a long-established uninfected central perforation becomes infected and extends to the mastoid (Fig. 140-4).

Masked Mastoiditis

Samuel and Fernandez14 described 21 cases of mastoiditis with retroauricular swelling and an intact tympanic membrane in a South African population (19 patients were <13 years old) in whom the duration of symptoms was shorter than that usually seen with coalescent mastoiditis. The predominant finding at mastoidectomy was granulation tissue filling the mastoid cavity and the antrum. The tympanic membrane was described as hyperemic, dull, bluish, bulging, or retracted. In addition to their mastoiditis, 10 patients had postauricular abscesses, 3 had Bezold’s abscesses, and 2 had facial nerve palsy. Four patients had cellulitis or abscess in the posterior fossa. Although these cases do not represent masked mastoiditis, they show the important fact that medically significant mastoiditis can exist without purulent otorrhea. There are two keys to the successful diagnosis and management of masked mastoiditis: (1) mastoid disease is not always reflected by the appearance of the tympanic membrane, and (2) chronic mastoiditis is a surgical condition, regardless of the appearance of the tympanic membrane. In this regard, the diagnosis and management of masked mastoiditis are no different from the diagnosis and management of mastoiditis with otorrhea emanating from other causes.

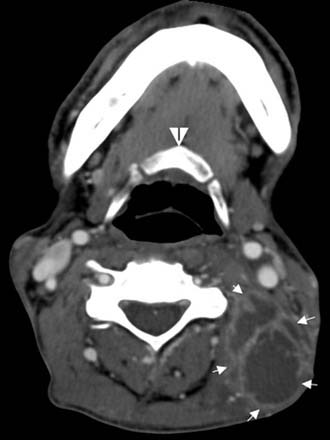

Postauricular Abscess

The diagnosis is usually obvious. Because only the upper part of the mastoid is pneumatized, the process develops in that upper portion, and the tissue edema and the abscess drive the auricle downward and laterally (Fig. 140-5). In the early stages, if fluctuation is not obvious, the clinician should use imaging studies or ultrasonography to document the presence of air within the soft tissue or an abscess cavity with its capsule (Figs. 140-6 and 140-7). When mastoiditis has produced an abscess, excision and drainage in conjunction with mastoidectomy is indicated. Only in the most unusual of circumstances would treatment by prolonged antibiotics and drainage of the abscess without mastoidectomy be appropriate.

Figure 140-5. Postauricular abscess associated with coalescent mastoiditis. Auricle is displaced laterally and inferiorly.

(From Harker LA. Cranial and intracranial complications of acute and chronic otitis media. In: Snow JB, Ballenger JJ, eds. Ballenger’s Otorhinolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery. 16th ed. Hamilton, Ontario: Decker; 2003.)

Bezold’s Abscess

In his 1913 text, Diseases of the Ear, Kerrison15 described a Bezold abscess as a condition:

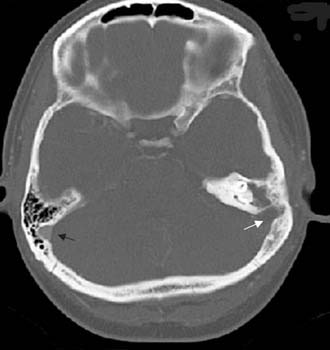

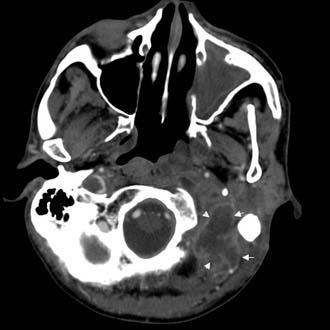

Often, the diagnosis of Bezold’s abscess is not considered initially in young patients with deep, tender, upper cervical masses because inflamed lymph nodes from many causes are so common. If the history and physical examination do not reveal a specific etiology, the clinician should obtain a CT scan to identify or rule out a mastoid source (Figs. 140-8 through 140-11).

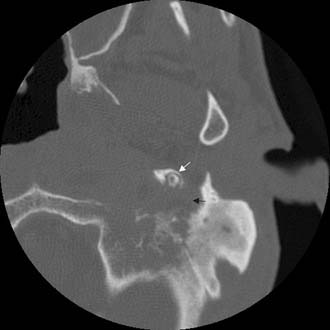

Figure 140-9. Axial temporal bone CT scan of the patient in Figure 140-8 at level of the root of styloid process (white arrow) showing destruction of bone at the anterior aspect of mastoid tip (black arrow).

Figure 140-10. CT scan of patient in Figure 140-8 showing Bezold’s abscess with enhancing capsule (arrows) at level of the mastoid tip.

Petrous Apicitis

Each petrous apex is undeveloped (sclerotic), contains marrow, or exhibits a variable degree of pneumatization. Pneumatization develops in only approximately 30% of temporal bones.12 Much has been written about the different cell tracts that extend into and pneumatize the petrous apex. Basically, the cells extend into the apex above (supralabyrinthine) (Fig. 140-12), behind (retrolabyrinthine) (Fig. 140-13), beneath (infralabyrinthine) (Fig. 140-14), or in front of the labyrinth (anterior labyrinthine). Petrous apicitis is essentially mastoiditis that occurs in the petrous apex. It is rare because infection in sclerotic apices or petrous apices containing marrow is uncommon, and because the prevalence of pneumatization is low. Petrositis develops by direct extension of a mastoid infection, but the mastoid may respond to medical or surgical treatment without apical resolution. Just as there can be disjunction between the state of infection in the middle ear and the mastoid, the same holds true between the mastoid and the petrous apex.

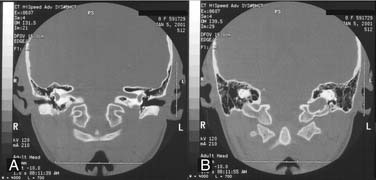

Figure 140-12. A and B, Petrous apex pneumatization via supralabyrinthine cell tract at level of vestibule (A) and posterior semicircular canal (B).

(From Harker LA. Cranial and intracranial complications of acute and chronic otitis media. In: Snow JB, Ballenger JJ, eds. Ballenger’s Otorhinolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery. 16th ed. Hamilton, Ontario: Decker; 2003.)

Figure 140-13. Petrous apex pneumatization via retrolabyrinthine cell tract at two levels of internal auditory canal and vestibule.

(From Harker LA. Cranial and intracranial complications of acute and chronic otitis media. In: Snow JB, Ballenger JJ, eds. Ballenger’s Otorhinolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery. 16th ed. Hamilton, Ontario: Decker; 2003.)

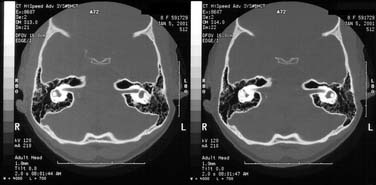

Figure 140-14. Petrous apex pneumatization via infralabyrinthine cell tract in right temporal bone at level of internal auditory canal.

(From Harker LA. Cranial and intracranial complications of acute and chronic otitis media. In: Snow JB, Ballenger JJ, eds. Ballenger’s Otorhinolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery. 16th ed. Hamilton, Ontario: Decker; 2003.)

The pathology of the infection can mirror that seen in coalescent mastoiditis, with dissolution of thin cellular septa and coalescence, or it can resemble the formation of granulation tissue with chronic bone erosion seen with chronic mastoiditis. Rarely, there is extension of cholesteatoma to the apex. Imaging studies usually include CT and MRI. CT scan shows the bony details of the septa of the air cells and the size and contour of the entire apex (Figs. 140-15 through 140-20). MRI differentiates marrow from mucus or CSF. CT and MRI studies are essential to establish when there is opacification of the air cells in the petrous apex under suspicion, as opposed to asymmetric pneumatization. When one petrous apex is well pneumatized, a small sclerotic or marrow-containing apex on the opposite side can be misinterpreted as a pneumatized apex opacified by fluid or infection.

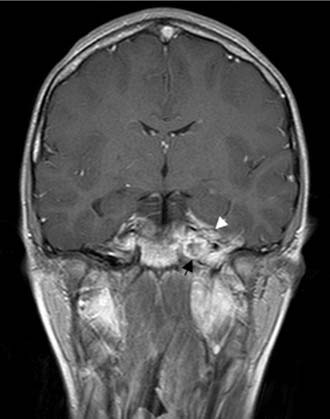

Figure 140-16. Axial non–contrast-enhanced T1-weighted MRI of the patient in Figure 140-15 showing mastoid opacification (star). The left petrous apex is also opacified (triangle) in contrast to the bright fat signal seen on the right side. Note narrow caliber of left internal carotid artery (short arrow) compared with internal carotid artery on the right (arrows).

Figure 140-17. Axial contrast-enhanced T1-weighted MRI of the patient in Figure 140-15 showing low signal in left petrous apex with peripheral contrast enhancement (black arrowhead) consistent with inflammation. Note narrow caliber of left internal carotid artery (short arrow) compared with internal carotid artery on the right (arrows).

Figure 140-18. Coronal contrast-enhanced T1-weighted MRI of the patient in Figure 140-15 showing low signal in left petrous apex with peripheral contrast enhancement (black arrow). Note enhancement of dura and temporal lobe adjacent to petrous apex (white arrowhead).

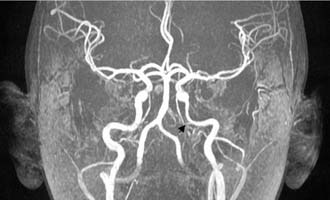

Figure 140-19. MR angiography of the patient in Figure 140-15 showing narrowing of left petrous internal carotid artery (arrow).

Figure 140-20. MR angiography of the patient in Figure 140-15 showing normal caliber of internal carotid artery after resolution of narrowing (arrow).

The symptoms of infection in the petrous apex reflect the innervation of the air cells and the structures adjacent to the apex itself. Although increased pressure within the mastoid air cell system causes pain in the region of the mastoid and the ear itself, pressure within the petrous apex usually results in pain referred to the retro-orbital area or deep within the skull. Patients with petrous apicitis can have symptoms that reflect infection in the middle ear and mastoid, and symptoms emanating from the apex. The most common symptoms are deep or retro-orbital pain (from irritation of the contiguous trigeminal ganglion in Meckel’s cave), paralysis of cranial nerve VI as it passes through Dorello’s canal abutting the petrous apex, dysfunction of cranial nerves VII and VIII, or labyrinthitis. In 1904, Gradenigo described the triad of retro-orbital pain, sixth cranial nerve paralysis, and otorrhea, since known as Gradenigo’s syndrome.12 Only a few patients with petrous apicitis exhibit the full triad today.

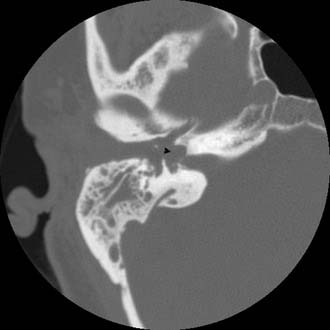

Labyrinthine Fistula

This bone resorption is almost exclusively secondary to cholesteatoma, and it occurred in 7% of the cholesteatomas in the large series by Gersdorff and Nouwen.16 Higher percentages have been reported, but the actual incidence is hard to determine. Most reports of labyrinthine fistulas caused by cholesteatoma are from tertiary care referral centers that include many large or previously operated cases, perhaps biasing the prevalence. Studies reviewing suppurative complications of otitis media usually do not include all cases of labyrinthine fistulas because many are not infected, or do not cause significant symptoms and are detected only at surgery. The mechanisms by which cholesteatoma causes this bony erosion are not fully understood, and are the subject of other chapters. Suffice it to say, first there is demineralization of the dense endochondral bone, and then loss of bone substance, so that the perilymph and its surrounding endosteal membrane have less and less bone between them and the overlying cholesteatoma matrix. As the bone becomes thin, it can be observed at surgery as a “blue line” parallel to the underlying semicircular canal lumen because the illuminating light along the blue line is no longer reflected off the dense bone, but absorbed into the underlying fluid.

Manolidis17 reviewed the records of 111 inner-city patients in Texas with labyrinthine fistulas, and assessed their coexisting complications. Two associations were prominent. The facial nerve was involved with cholesteatoma or functionally damaged by a cholesteatoma in 60% of the patients, and dehiscences of the tegmen occurred in 39%. Most of these cases were reoperations, with an average of 2.6 operations per patient. Although the data are biased by the number of revision operations, surgeons should always assume that the bony fallopian canal is eroded and the facial nerve is in direct contact with cholesteatoma whenever a lateral semicircular canal fistula is suspected, and they should consider the possibility of defects in the tegmen in such patients, especially patients with previous mastoid surgery.

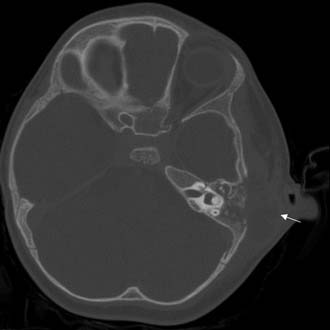

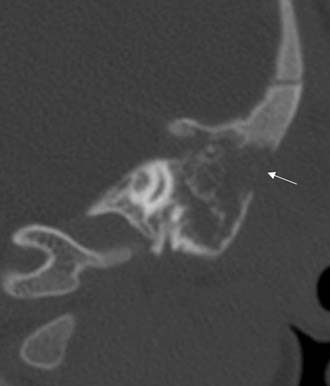

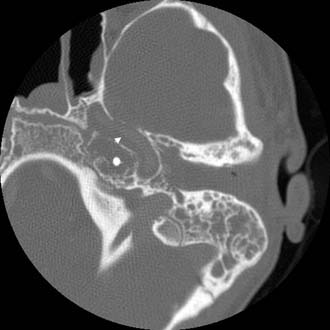

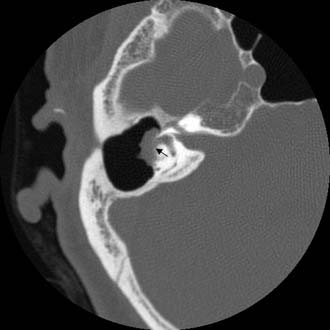

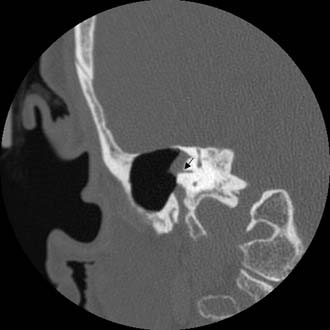

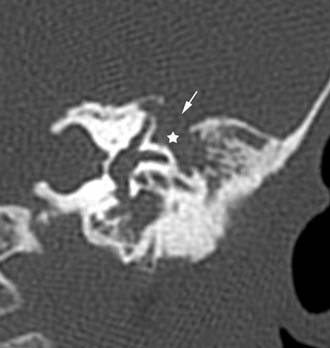

The fistula test results are reported as positive in only 55% to 70% of patients with lateral canal erosion, but if positive, they are highly reliable and facilitate surgical planning and execution.18 CT scanning (Figs. 140-21, 140-22, and 140-23) also provides preoperative evidence suggesting a labyrinthine fistula, and images in the bone algorithm usually document the bone erosion of the lateral semicircular canal and show other signs suggestive of cholesteatoma.

Figure 140-21. Axial temporal bone CT scan showing soft tissue density in a mastoid cavity eroding into horizontal semicircular canal (arrow).

Figure 140-22. Axial temporal bone CT scan of the patient in Figure 140-21 showing erosion of anterior limb of superior semicircular canal (arrowhead).

Figure 140-23. Coronal temporal bone CT scan of the patient in Figure 140-21 showing erosion of horizontal semicircular canal (arrow).

Removal of the fistula generally improves the vestibular symptoms, although symptoms related to pressure transmitted from the external auditory canal can persist for some time. Because there is no protective bone to prevent compression of the endolymphatic compartment by pressure changes in the external auditory canal, a positive fistula sign persists until there is a regrowth of bone. Loss of hearing in the involved ear and worsening of existing hearing are the risks that always accompany the procedure, but these have been reported to occur in less than 20% of carefully managed fistula cases.9

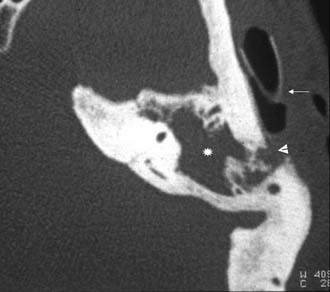

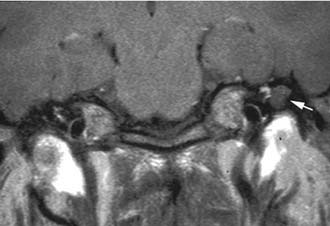

Facial Nerve Paralysis

Facial nerve paralysis caused by COM without cholesteatoma also usually affects the horizontal portion of the facial nerve near the stapes.19 In these cases, the clinical course of the paralysis is more likely to be prolonged, with a gradual progression from slight weakness to full paralysis; sometimes the progression to complete paralysis is rapid (Figs. 140-24 and 140-25). Facial nerve paralysis caused by cholesteatoma can produce extensive erosion of the horizontal segment of the fallopian canal—especially common in large, uninfected, primary acquired cholesteatomas. An erosive cholesteatoma can expose the facial nerve anywhere in the temporal bone and cause paralysis. In these cases, the onset of the paralysis is usually gradual, and sometimes the progression is so slow that patients do not seek medical attention for months. When the onset of facial paralysis is this slow, the paralysis is more likely to persist after surgical treatment.

Figure 140-24. Coronal temporal bone CT scan showing cholesteatoma (arrow) eroding the facial nerve canal (arrowhead).

Acute Suppurative Labyrinthitis

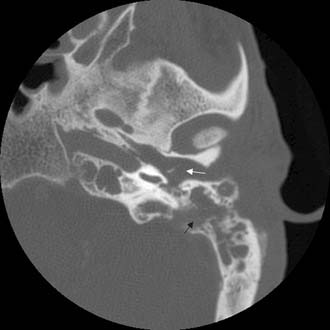

Bacterial invasion of the labyrinth is always promptly followed by total loss of auditory and vestibular function (Figs. 140-26 through 140-29). Usually, AOM extends into the labyrinth through a weakened or dehiscent oval window membrane, as occurs in congenital labyrinthine deformities such as Mondini’s deformity and enlarged vestibular aqueducts, and in individuals who have undergone stapes surgery. Although it is not proven, suppurative labyrinthitis may be a common mechanism for unilateral anacusis in children with Mondini’s deformity. These children are at additional risk. The foramina of the internal auditory canal opening into the medial aspects of the labyrinth may also be weak or dehiscent, and those foramina and the cochlear aqueduct can permit bacterial infection to progress from the labyrinth to the meninges or vice versa. It is unknown how frequently suppurative labyrinthitis causes meningitis, or how often meningitis subsequently causes bacterial labyrinthitis, but both probably occur, especially in the special population of children with congenital labyrinthine abnormalities.

Figure 140-27. Coronal temporal bone CT scan of the patient in Figure 140-26. Note the erosion and involvement of the fundus of the internal auditory canal (arrowhead).

Figure 140-28. Axial contrast-enhanced T1-weighted MRI of the patient in Figure 140-26 showing enhancement of middle ear, vestibule, and internal auditory canal (arrowhead).

Encephalocele and Cerebrospinal Fluid Leakage

Spontaneous CSF leakage sometimes develops in conjunction with defects in the tegmen tympani or, less commonly, the tegmen mastoideum. May and colleagues,20 Lundy and associates,21 and others have reported this in more than 50 patients who have not undergone previous otologic surgery. Of such patients, 70% to 80% are older than 45 years. The defects range in diameter from 2 mm to 2 cm, and sometimes are multiple. Usually, an encephalocele protrudes through the defect (Figs. 140-30 and 140-31). There is no agreement as to why the dura breaks down and allows protrusion of cerebral contents and escape of CSF in these older patients, although Jackson and colleagues22 have suggested that aging, increased intracranial pressure, low-grade inflammation, arachnoid granulation, and irradiation can play a part. Patients frequently visit their physicians because of hearing loss secondary to reduced ossicular motion from the middle ear fluid or the encephalocele. Myringotomy and placement of a ventilating tube manifest profuse watery otorrhea that tests positive for CSF. Other patients present with signs and symptoms of meningitis, and many of these patients have experienced one or more previous bouts of that disease.

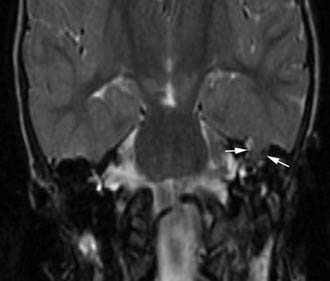

Figure 140-30. Coronal temporal bone CT scan showing encephalocele (star) going through a tegmen defect (arrow).

Figure 140-31. Coronal T2-weighted MRI of the patient in Figure 140-30 showing encephalocele (arrows).

Traumatic encephalocele and CSF leakage is the most common pattern. Although a few of these cases occur because of temporal bone fracture, most are a consequence of surgical trauma, such as when portions of the tegmen or cerebellar plates have been surgically removed, and the dura is exposed and sometimes traumatized. In these situations, the disease process and the surgery can contribute to the bony and dural trauma that facilitates the development of an encephalocele, CSF leakage, and intracranial complications. Manolidis23 reported a series of 29 such patients from an inner-city population. More than 80% of the patients had cholesteatoma, and half had undergone one or two previous operations. All had dural herniations and encephaloceles, but only one had CSF leakage. Labyrinthine fistulas, suppurative intracranial complications, and associated facial paralysis were noted.

Jackson and colleagues22 have written an excellent review of this subject. The size of the bony defect and the volume of herniated brain are two of the important factors in choosing a surgical approach. Small defects are managed adequately through the mastoid; multiple and larger defects are repaired by the middle cranial fossa approach in combination with mastoid exposure.

Intracranial Complications

Meningitis

In the past, meningitis was the most common complication of AOM and COM. In the series by Gower and McGuirt24 of 100 consecutive patients with intracranial complications of AOM and COM, 76 had meningitis, and 53 of those patients were younger than 2 years. In that age group, most cases occurred by hematogenous dissemination of infection during AOM. Sometimes, these patients are not tabulated in reports documenting the complications of otitis,1,25 and in those reports the frequency of otitis-induced meningitis is low.

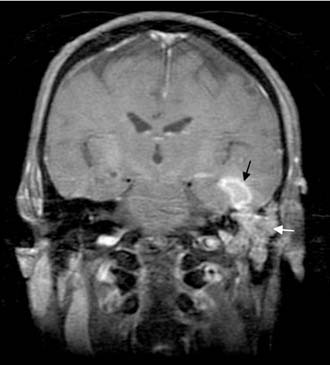

When meningitis is caused by AOM or suppurative labyrinthitis, myringotomy and appropriate antibiotics are adequate, and no surgery is indicated. When meningitis develops from COM and mastoiditis, however, the mastoid must be exenterated. When otogenic meningitis is associated with a profound ipsilateral sensorineural hearing loss, a route of infection to the meninges through the labyrinth is apparent. If the sensorineural function in the affected ear remains at the patient’s premeningitis baseline, the route was extralabyrinthine. Some patients with severe AOM experience a partial sensorineural hearing loss because of associated serous labyrinthitis. This partial loss may be reversible. Although the patient has already had a CT scan before the lumbar puncture, an enhanced MRI study should be obtained to rule out the presence of any additional intracranial complications (Fig. 140-32). The neurologic condition of the patient determines the timing of the surgery, and the mastoidectomy should be performed as soon as the patient is stable. Meningitis is one of the gravest complications of acute or chronic otitis, and it seems that it is more lethal when caused by COM and mastoiditis than when it is a hematogenous complication of AOM in the first 2 years of life.

Brain Abscess

The incidence and mortality of intraparenchymal brain abscesses have decreased considerably, and almost all reports in the past 2 decades are from centers outside North America and Western Europe. Excellent reports from Africa and Asia using new imaging techniques have documented improvements in diagnosis and therapy, however, and have clarified some aspects of surgical treatment. The series by Yen and colleagues26 of 122 consecutive patients seen in a Taiwan hospital between 1981 to 1994 revealed that otogenic causes were the third most common cause of intraparenchymal brain abscess, exceeded only by causes associated with cyanotic congenital heart disease and abscesses resulting from head injury or neurosurgery. Seventy-five percent of abscesses occurred in male patients—principally individuals in the lower socioeconomic classes. In the 1990s, four reports from India, Turkey, and South Africa discussed 149 patients with otogenic brain abscesses.1,2,27,28 Abscesses from AOM and COM were almost always found on the same side as the otitis and occurred nearly equally in the temporal lobe and cerebellum. Almost three fourths were secondary to cholesteatoma, 50% occurred in the second decade of life, and two thirds affected male patients.

A brain abscess begins when bacteria propagate in and around venous channels leading from the mastoid into the adjacent brain parenchyma. The first event after the arrival of bacteria into the cortex or white matter is the migration of polymorphs into local capillaries with endothelial swelling and focal cerebritis. At this stage, the disease can be successfully managed by intravenous antibiotics alone. With more time, the tissue becomes edematous, hemorrhagic, and necrotic, and the abscess is formed. Brain abscesses may vary greatly in size, often have an irregular shape, and frequently are multilocular. At first, the capsule is poorly defined, but over time it becomes firmer and can easily be stripped from the underlying edematous brain.29

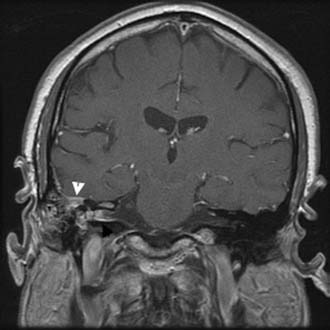

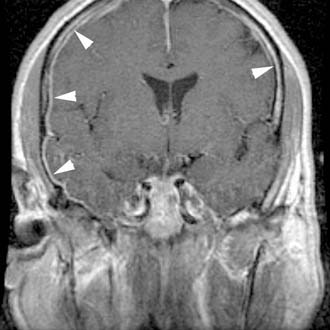

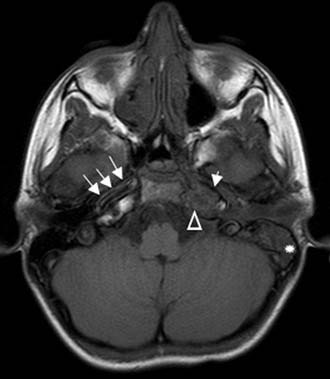

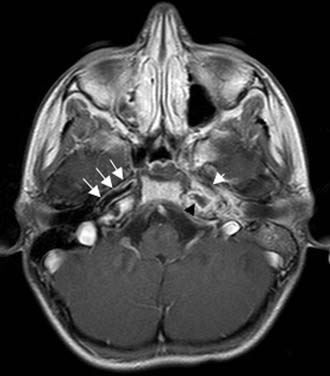

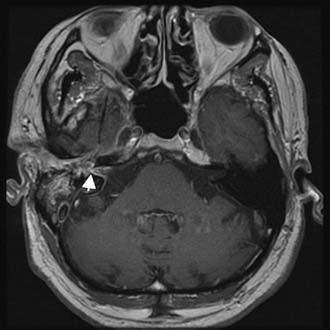

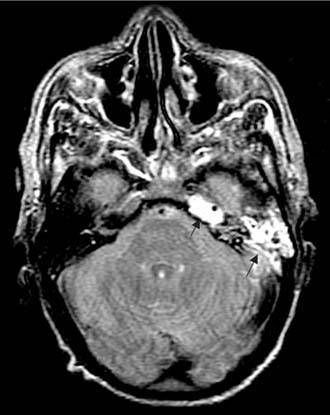

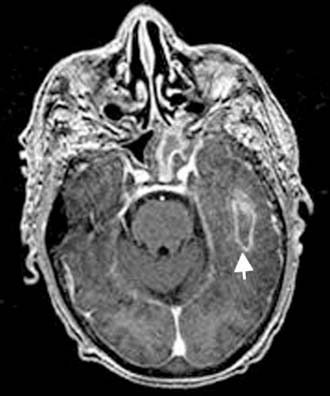

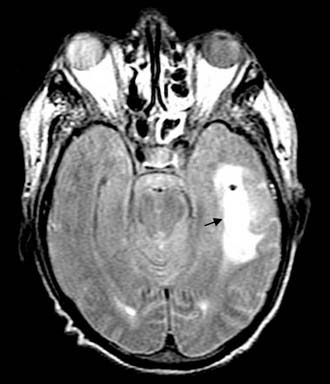

In addition to symptoms and signs reflecting general intracranial sepsis, cerebellar abscess is often accompanied by coarse horizontal nystagmus, dysmetria, dysdiadochokinesia, or action tremor. Temporal lobe abscess (Figs. 140-33 through 140-36) can cause homonymous visual field defects, contralateral hemiparesis, and other focal signs listed later for subdural empyema. The physician should examine the patient and the imaging studies looking for other intracranial complications because two thirds of patients with intraparenchymal abscesses have more than one intracranial complication.27

Figure 140-33. Axial T2-weighted MRI showing left mastoiditis and petrous apicitis (arrows) as high signal in mastoid and petrous apex.

Figure 140-34. Axial contrast-enhanced T1-weighted MRI of the patient in Figure 140-33 showing left temporal lobe abscess with enhancing capsule (arrow).

Figure 140-35. Axial T2-weighted MRI of the patient in Figure 140-30 showing abscess cavity and surrounding edema (arrow).

Subdural Empyema

Subdural empyema is a fulminating purulent infection that develops between the dura and the pia arachnoid membranes, and represents one of the most immediate of neurosurgical emergencies. It constitutes only about 20% of all cases of localized intracranial bacterial infection, and an otologic etiology is uncommon compared with bacterial contamination (from trauma or a neurosurgical operation), suppurative sinus disease, and meningitis. At least two thirds of the cases occur in men, and most occur in the second decade of life. The abscess usually begins by direct spread from adjacent infected bone or by retrograde venous propagation. When infection enters the subdural space, pus forms rapidly and spreads widely, and thrombophlebitis of cortical veins is virtually guaranteed. Swelling, necrosis, and infarction of the cortex accounts for many of the clinical features and explains how a barely detectable thin layer of subdural pus can cause such devastating consequences as increased intracranial pressure, focal signs, and seizures.30

Subdural empyema can also develop in neonates as a complication of meningitis. In 30% of cases of H. influenzae meningitis, a collection of fluid develops in the subdural space (usually bilaterally) that varies from 5 to 100 mL.31 This problem is less common after meningitis from other organisms and is decreasing in frequency because universal immunization against H. influenzae has dramatically reduced the incidence of meningitis. Uninfected subdural collections after meningitis are called subdural effusions. If bacteria are evident on direct examination of the fluid, the collections are called infected subdural effusions, and if the fluid is grossly purulent, they are classified as subdural empyemas. Subdural collections from meningitis secondary to COM that require otologic attention are rare in the neonatal age group.

Lateral Sinus Thrombosis

Thrombosis of the lateral sinus usually forms as an extension of a perisinus abscess that develops after mastoid bone erosion from cholesteatoma, granulation tissue, or coalescence (Figs. 140-37 and 140-38).32 The perisinus abscess exerts pressure on the dural outer wall of the sinus leading to necrosis. The necrosis extends to the intima and attracts fibrin, blood cells, and platelets. A mural thrombus forms, then becomes infected, enlarges, and occludes blood flow through the sinus. Fresh thrombus can propagate and extend in a retrograde direction to the transverse sinus (Fig. 140-39), to the torcular Herophili, and even to the superior sagittal sinus. In the opposite direction, the clot can extend via the jugular bulb into the internal jugular vein in the neck, and can extend to the cavernous sinus via the inferior or superior petrosal sinus. The infected clot frequently showers the bloodstream with bacteria, giving rise to the signs and symptoms of septicemia and the possibility of metastatic abscesses (most commonly to the lungs).

Figure 140-38. Coronal contrast-enhanced CT scan of the patient in Figure 140-37 showing absent flow in left internal jugular vein at the skull base (white arrow) and normal flow in right internal jugular vein (black arrow).

Figure 140-39. MR venogram showing occlusion of left transverse–sigmoid sinus system.

(From Head and Neck Archive, Advanced Medical Imaging Reference Systems [AMIRSYS], Salt Lake City, UT. Accessed January 2003.)

Because the sinus is a continuation of the cerebellar dura mater, extension of an infection by only a few millimeters can result in meningitis, epidural abscess, subdural empyema, cerebritis, or cerebellar abscess, all equally grave complications. In two series,32,33 14 of 19 patients with lateral sinus thrombosis had one or more of these additional complications.

Although the frequent association with other complications tends to obscure the clinical picture, the diagnosis of lateral sinus thrombosis can be strongly suspected when there are signs and symptoms of septicemia or blockage of blood flow through the sinus. The picket-fence fever pattern with diurnal temperature spikes exceeding 103° F has been described with this condition for decades. Although some more recent articles have pointed out that this pattern is not seen as frequently, in part because many patients present with previous or current antibiotic therapy, most of the 36 patients reported by Singh25 were receiving intravenous antibiotics and still exhibited that fever pattern. Unless the patient has been transferred from another hospital, on admission there is only one temperature measurement to observe. Nonetheless, a single high fever reading should alert the clinician to the possibility of sigmoid sinus thrombophlebitis. Singh25 also pointed out that the neck pain in lateral sinus thrombosis may be mistakenly attributed to the neck stiffness of meningitis, when it actually represents pain and tenderness along the anterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle, and he suggested that percussion tenderness of the mastoid tip is another important sign.

Imaging studies and lumbar puncture are essential to sort out the possible types of complications in obtunded patients. If the patient’s condition permits, contrast-enhanced CT scan and contrast-enhanced MRI should be performed (see Fig. 140-32). The delta sign seen on the CT scan, enhancement of the wall of the sigmoid sinus, allows preoperative diagnosis. Wall enhancement is more sensitively evaluated by MRI, which can also document abscess formation within the sinus and exclude adjacent subdural empyema, cerebritis, or cerebellar abscess.

The sinus is usually addressed only after mastoidectomy. The sinus and adjacent dura are addressed by removing the overlying bone. The surgeon passes an 18- or 20-gauge needle through the sinus wall, and if there is no free blood on aspiration, a linear incision is made through the sinus wall, and the abscess and any infected clots are evacuated. Further sinus incision can enable clot evacuation proximally and distally until free bleeding occurs. The mastoid and cerebellar walls of the sinus are usually thick and indurated as a result of the chronic infection. The surgeon can safely scrape them gently with a broad flat instrument such as a Freer elevator to remove the infected tissue. Syms and colleagues33 reported treating six patients with lateral sinus thrombosis and concomitant intracranial complications with mastoidectomy, but without opening and evacuating the lateral sinus clot. All patients survived, but the average hospital stay was more than 49 days; it was 38 days when the patient with the longest stay was not included. In contrast, patients reported by Kaplan and Kraus32 underwent surgery that included incision of the sinus and evacuation of the clot or abscess, and their mean hospital stay was only 17 days.

Otitic Hydrocephalus

Some authors view otitic hydrocephalus as a distinct clinical entity consisting of intracranial hypertension and resolved or resolving (usually acute) otitis media, having no relationship to lateral sinus thrombophlebitis.24 Others view it more as a pathophysiologic consequence of lateral sinus thrombosis that occurs more commonly as a result of AOM than COM and depends on the three factors mentioned in the previous paragraph. The distinction is less important than recognizing the relationship between the symptom complex, ear disease, lateral sinus, and emergent nature of the treatment.

Brackmann DE, Clough Shelton C, Arriaga MA, editors. Otologic Surgery. Philadelphia: Saunders, 2001.

Dhepnorrarat RC, Wood B, Rajan GP. Postoperative non-echo-planar diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging changes after cholesteatoma surgery: implications for cholesteatoma screening. Otol Neurotol. 2009;30:54-58.

Harker LA. Cranial and intracranial complications of acute and chronic otitis media. In: Snow JB, Ballenger JJ, editors. Ballenger’s Otorhinolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery. 16th ed. Hamilton, Ontario: Decker; 2003:294-316.

Limb CL, Lustig LR, Niparko JK. Infections of the ear: acute and chronic disease. In: Lustig LR, Niparko J, Zee D, Minor L, editors. Clinical Neurotology. London: Martin-Dunitz, Taylor & Francis, Informa HealthCare; 2003:133-145.

Naclerio R, Neely JG, Alford BR. A retrospective analysis of the intact canal wall tympanoplasty with mastoidectomy. Am J Otol. 1981;2:315-317.

1. Singh B, Maharaj TJ. Radical mastoidectomy: its place in otitic intracranial complications. J Laryngol Otol. 1993;107:1113-1118.

2. Osma U, Cureoglu S, Hosgoglu S. The complications of chronic otitis media: report of 93 cases. J Laryngol Otol. 2000;114:97-100.

3. Gates GA. Acute otitis media and otitis media with effusion. In Cummings CW, editor: Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery, 3rd ed, St Louis: Mosby-Year Book, 1998.

4. Harker LA, Koontz FP. The bacteriology of cholesteatoma. In: McCabe BF, Sade J, Abramson M, editors. Cholesteatoma First International Conference. Birmingham, AL: Aesculapius, 1977.

5. Dobbin GD, Raofi B, Mafee MF, et al. Otogenic intracranial inflammations: role of magnetic resonance imaging. Top Magn Reson Imaging. 2000;11:76-86.

6. Latchaw RE, Hirsh WL, Yock DHJr. Imaging of intracranial infection. Neurosurg Clin North Am. 1992;3:303-322.

7. Luntz M, Brodsky A, Nusem S, et al. Acute mastoiditis—the antibiotic era: a multicenter study. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2001;57:1-9.

8. Lee ES, Chae SW, Lim HH, et al. Clinical experiences with acute mastoiditis: 1988 through 1998. Ear Nose Throat J. 2000;79:884-891.

9. Bak-Pedersen K, Ostri B. Labyrinthine fistula in chronic otitis media with cholesteatoma. In: Tos M, editor. Cholesteatoma and Mastoid Surgery. Amsterdam: Kugler & Ghedini Publications, 1989.

10. Van Zuijlen DA, Schilder AG, Van Balen FA, et al. National differences in incidence of acute mastoiditis: relationship to prescribing patterns of antibiotics for acute otitis media? Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2001;20:140-144.

11. Dew LA, Shelton C. Complications of temporal bone infections. In Cummings CW, editor: Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery, 3rd ed, St Louis: Mosby-Year Book, 1998.

12. Neely JG. Complications of temporal bone infection. In Cummings CW, editor: Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery, 2nd ed, St Louis: Mosby-Year Book, 1993.

13. Go C, Bernstein JM, de Jong AL, et al. Intracranial complications of acute mastoiditis. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2000;52:143-148.

14. Samuel J, Fernandez C. Otogenic complications with an intact tympanic membrane. Laryngoscope. 1985;95:1387-1390.

15. Kerrison PD. Diseases of the Ear. Philadelphia: Lippincott; 1913.

16. Gersdorff MC, Nouwen J. Labyrinthine fistula after cholesteatomatous chronic otitis media. Am J Otol. 2000;21:32-35.

17. Manolidis S. Complications associated with labyrinthine fistula in surgery for chronic otitis media. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2000;123:733-737.

18. Soda-Merhy A, Betancourt-Suarez M. Surgical treatment of labyrinthine fistula caused by cholesteatoma. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2000;122:739-742.

19. Harker LA, Pignatari S. Facial nerve paralysis secondary to chronic otitis media without cholesteatoma. Am J Otol. 1992;13:372-374.

20. May JS, Mikus JL, Matthews BL, et al. Spontaneous cerebrospinal fluid otorrhea from defects of the temporal bone: a rare entity? Am J Otol. 1995;16:765-771.

21. Lundy LB, Graham MD, Kartush JM, et al. Temporal bone encephalocele and cerebrospinal fluid leaks. Am J Otol. 1996;17:461-469.

22. Jackson DG, Pappas DGJr, Manolidis S, et al. Brain herniation into the middle ear and mastoid: concepts in diagnosis and surgical management. Am J Otol. 1997;18:198-206.

23. Manolidis S. Dural herniations, encephaloceles: an index of neglected chronic otitis media and further complications. Am J Otolaryngol. 2002;23:203-208.

24. Gower D, McGuirt WF. Intracranial complications of acute and chronic infectious ear disease: a problem still with us. Laryngoscope. 1983;93:1028-1033.

25. Singh B. The management of lateral sinus thrombosis. J Laryngol Otol. 1993;107:803-808.

26. Yen PT, Chan ST, Huang TS. Brain abscess: with special reference to otolaryngologic sources of infection. Otolaryngol Head and Neck Surg. 1995;113:15-22.

27. Kurien M, Job A, Mathew J, et al. Otogenic intracranial abscess. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1998;124:1353-1356.

28. Murthy P, Sukumar R. Otogenic brain abscess in childhood. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 1991;22:9-17.

29. Reid H, Fallon RJ. Bacterial infections. In: Adams JH, Duchen LW, editors. Greenfield’s Pathology. New York: Oxford University Press, 1992.

30. Kerr RSC, Mitchell RG. Abscess. In: Swash M, Oxbury J, editors. Clinical Neurology. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 1991.

31. Bell WE, McCormick WF. Neurologic Infections in Children. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1981.

32. Kaplan DM, Kraus M. Otogenic lateral sinus thrombosis in children. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 1999;49:177-183.

33. Syms MJ, Tsai PD, Holtel MR. Management of lateral sinus thrombosis. Laryngoscope. 1999;109:1616-1620.