Chapter 5 Complications of Intrathecal Drug Delivery Systems

Complications of Needle Placement in the Intrathecal Space

Bleeding

During the placement of an intrathecal catheter, the needle typically passes through the epidural space with little trauma. However, in anticoagulated patients and in patients with bleeding dyscrasias, epidural bleeding and resultant epidural hematomas are a significant risk (Table 5-1). Epidural bleeding is likely common but usually goes unnoticed in the absence of postoperative imaging studies. Rarely, an epidural bleed may produce a clinically significant epidural hematoma. Untreated, an epidural hematoma can progress and result in numbness, weakness, increased pain, and ultimately paralysis. If the development of an epidural hematoma is suspected, the patient should undergo immediate magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and surgical evaluation. Prompt hematoma evacuation should be performed within 12 hours of the onset of symptoms because evacuation within this time frame has been associated with better neurological outcomes. Any patient complaining of weakness in the postoperative period should undergo immediate evaluation for the presence of an epidural hematoma (Box 5-1).

Table 5-1 Commonly Used Drugs That May Result in Increased Risk of Bleeding Complications

| Brand Name | Generic |

|---|---|

| Angiomax | Bivalirudin |

| Arixtra | Fondaparinux |

| Jantoven | Coumadin |

| Fragmin | Dalteparin |

| Innohep | Tinzaparin |

| Lovenox | Enoxaparin |

| Argatroban | Argatroban |

| ATryn | Antithrombin |

| None | Heparin |

| Iprivask | Desirudin |

| Refludan | Lepirudin |

| Thrombate | Antithrombin |

| Pradaxa | Dabigatran |

| Aggrenox | Aspirin/dipyridamole |

| Effient | Prasugrel |

| Plavix | Clopidogrel |

| Pletal | Cilostazol |

| ReoPro | Abciximab |

| Ticlid | Ticlopidine |

| Aggrastat | Tirofiban |

| Agrylin | Anagrelide |

| Integrilin | Eptifibatide |

| Persantine | Dipyridamole |

Recommendations for Avoiding Bleeding-Associated Complications

Today physicians encounter many patients that are anticoagulated with medications such as antifibrinolytic and antiplatelet agents. Discontinuing antifibrinolytic medications for 7 to 10 days has previously been recommended, but there are no data to establish when it is safe to perform neuraxial procedures in patients treated with these medications.1 Additionally, there has never been a clear relationship established between aspirin and nonsteroidal administration and epidural hematoma formation. Most physicians do not require patients to discontinue low-dose aspirin and nonsteroidal antiinflammatory medications before undergoing implantation of an ITDD device. Recommendations published by the American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Management attempt to provide guidelines for discontinuing anticoagulation in patients who are to undergo neuraxial procedures.1

Infection

Risks factors for infection include any patient with a history of immunocompromised state such as HIV infection, history of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection, organ transplantation, cancer, diabetes mellitus, and skin infections at the time of implantation (Box 5-2). Transverse myelitis is uncommon but is seen with catheter infections and may not be present with known infection.2 Routine laboratory studies, including C-reactive protein (CRP), complete blood count (CBC) with differential, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), should be obtained in patients with clinical symptoms of infection.

Catheter-Associated Complications

Granuloma Formation

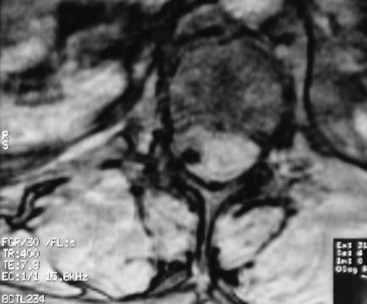

Aside from infection, the development of catheter granulomas is one of the most serious complications associated with intrathecal catheters. First reported in 1999, granulomas (Fig. 5-1) appear to be inflammatory, fibrotic, noninfectious masses that develop at the tip of the catheter.3 The mass formation usually develops over months to years and is more likely to form in patients receiving high concentrations of morphine and hydromorphone.4 Consensus recommendations have suggested limiting morphine to 20 mg/cc and hydromorphone to 10 mg/cc (Table 5-2).

| Drug | Maximum Concentration | Maximum dose per day |

|---|---|---|

| Morphine | 20 mg/cc | 15 mg |

| Hydromorphone | 10 mg/cc | 4 mg |

| Fentanyl | 2 mg/cc | No upper limit |

| Sufentanil | 50 µg/cc | No upper limit |

| Bupivacaine | 40 mg/cc | 30 mg |

| Clonidine | 2 mg/cc | 1 mg |

| Ziconotide | 100 µg/cc | 19.2 µg |

Mechanical Complications

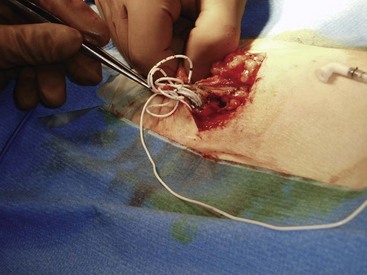

Catheter fracture may occur throughout the length of the catheter but frequently occurs at points of higher stress, which include the site of anchor, catheter splice junctions such as in two-piece catheters, and on the nipple of the reservoir. Catheter failure has been reported to be 4.5% during the first nine months following implantation.5 It is important to obtain control of the distal piece of the fractured catheter that typically occurs at the anchoring site. This can be accomplished by opening the anchor incision first and removing the distal catheter before opening the reservoir pocket. In some cases, catheter fracture may be managed with a splicing kit. If the distal catheter piece is irretrievable, a neurosurgical consultation should be obtained.

Another possible complication may result from migration of the catheter from the intrathecal space (Fig. 5-2). This obviously requires catheter revision and can result in side effects that range from the mundane to the serious. Migration into the epidural space may lead to CSF leak with resultant headache, loss of analgesia, and possibly hygroma formation. It is possible for the catheter to migrate into the neural foramen, which may lead to nerve root irritation and the development of radicular symptoms. Migration into the spinal cord is possible with the development of severe neurologic deficits. Any patient suspected of catheter malfunction should undergo plane radiographic imaging to assess for catheter integrity and MRI imaging with appropriate precautions if migration is suspected. Improper catheter anchoring techniques, such as failure to anchor to the thoracolumbar fascia, increase the likelihood of catheter migration.

Reservoir Pocket and Anchor Incision Complications

Infection

Infectious complications of the pocket and anchor site incisions related to ITDD devices have been reported to range from 2.5% to 9.0% and represent the most common type of infectious complications that the physician implanter is likely to encounter.6 Risk factors for infections of the reservoir pocket and anchor site are the same as discussed previously regarding catheter-related infections. Any patient presenting with pain over the incision site, swelling, rubor, or purulent discharge should be suspected of infection (Figs. 5-3 and 5-4). Aggressive management of superficial infections may prevent penetration into the subfascial layers and compromise of the device.

Hematoma

Careful attention to wound hemostasis, including meticulous tissue dissection, suturing of arterial bleeding, and use of coagulation for small vessel bleeding, may prevent the development of wound hematomas. The physician implanter should assess the patient’s risk of bleeding preoperatively. If a wound hematoma develops (Fig. 5-5), the physician should consider prompt evacuation and correction of any bleeding diathesis to prevent wound dehiscence and loss of the implant. Additionally, hematomas may predispose the implant to infection.

Complications Associated with Intrathecal Medications

Currently, morphine and ziconotide are the only two medications approved by the Food and Drug Administration for intrathecal use. Bupivacaine, fentanyl, sufentanil, hydromorphone, and clonidine are frequently used off label for intrathecal infusions in the treatment of chronic and cancer pain. Side effects of intrathecal opioid medications include nausea, constipation, urinary retention, confusion, dizziness, impotence and decreased libido, hypotension, pruritus, allergic reaction, somnolence, respiratory depression, and weight gain (Table 5-3).5,7 Adjunctive medications such as bupivacaine and clonidine may cause hypotension. As discussed previously, granulomas likely result from high concentrations of primarily intrathecal morphine and hydromorphone.4 The incidence of peripheral edema has been reported to range from 1% to 20% and is thought to result from the effect of opioids on the pituitary adrenal axis.8

Table 5-3 Reported Complications of Intrathecal Drug Delivery

| Author, Year | Reported Complications |

|---|---|

| Duse et al,10 2009 | None observed |

| Doleys et al,11 2006[11]11 | None observed |

| Penn and Paice,12 1987 | None observed |

| Atli et al,13 2010 | 14 complications of 57 patients reported: one with wound infection, two with granulomas, two with pocket seromas, three with catheter fracture; overall complication rate, 20%; failure of treatment, 24% |

| Ilias et al,14 2008 | No serious adverse outcomes reported; 92 patients reported 181 complications; 16% were pump programming related and resolved with reprogramming; 32% were drug related and benign |

| Ellis et al,15 2008 | Side effects related to ziconotide were reported in 147 of 155 patients; the most common reported side effect was confusion; 39.4% of patients discontinued treatment because of side effects |

| Shaladi et al,16 2007 | One patient with reported delayed wound healing and one with wound infection; some patients reported drug-related side effects |

| Thimineur et al,2 2004 | One patient developed transverse myelitis with permanent neurologic sequelae; one patient had catheter kinking, and two developed wound infections |

| Deer et al,17 2004 | Patient-reported complication rates were infection, 2.2%; migration, 1.5%; CSF leak, 0.7%; catheter kinking, 1.5%; catheter fracture, 0.7%; reaction to medication, 5.1%; overall, 23 patients reported complications, and 21 required surgical revision |

| Rauck et al,18 2003 | 40 of 119 patients implanted with IT pumps reported complications: seven developed device failures, and 36 had procedure-related complications |

| Deer et al,19 2002 | Patient-reported medication side effects included peripheral edema and paresthesias; no long-term ill effects of IT reported |

| Smith et al,20 2002 | 194 serious complications reported in 202 patients; 16 procedure-related adverse events reported of which six were device related, five were insertion related, and five were catheter related; 10 patients required surgical revision, and 1 pump was explanted because of infection |

| Rainov et al,21 2001 | 26 patients were implanted with IT pump; there were two device-related complications reported as catheter leakage and leakage; one pump was filled incorrectly, leading to damage to the reservoir septum and medication leakage |

| Becker et al,22 2000 | Five patients reported IT pump-related complications: one pocket hematoma, one postoperative case of pneumonia, and three catheter-related complications |

| Roberts et al,23 2001 | 40% (32) of patients developed technical complications primarily related to the catheter requiring surgical revision |

| Anderson and Burchiel24 1999 | No serious complications reported; two patients developed PDPHs, two patients had pump malfunctions, five patients required revision of the pump because of device-related issues, and one pump was programmed incorrectly |

| Winkelmuller and Winkelmuller,5 1996 | 31 of 120 patients implanted with IT pumps were considered treatment failures; 14 pumps required surgical revision |

| Onofrio and Yaksh,25 1990 | Human error lead to five pumps running out of medication |

PDPH, postdural puncture headache; IT, intrathecal therapy.

Recently, Coffey et al9 retrospectively investigated mortality and intrathecal drug delivery for non-cancer pain. Although they reported a 3.89% mortality rate at 1 year after implantation of an ITDD device, the deaths described can be attributed to a lack of vigilance and poor insight into the predictable consequences of mismanaged intrathecal therapy (i.e., respiratory depression). This report underscores the importance of vigilance in reducing iatrogenic error.

1 Horlocker TT, Wedel DJ, Benzon H, et al. Regional anesthesia in the anticoagulated patient: defining the risks (the second ASRA Consensus Conference on Neuraxial Anesthesia and Anticoagulation). Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2003;28(3):172-197.

2 Thimineur MA, Kravitz E, Vodapally MS. Intrathecal opioid treatment for chronic non-malignant pain: a 3-year prospective study. Pain. 2004;109(3):242-249.

3 North RB. Spinal cord compression by catheter granulomas in high-dose intrathecal morphine therapy: case report. Neurosurgery. 1999;44(3):691.

4 Coffey RJ, Burchiel K. Inflammatory mass lesions associated with intrathecal drug infusion catheters: report and observations on 41 patients. Neurosurgery. 2002;50(1):78-86. discussion 86-87

5 Winkelmuller M, Winkelmuller W. Long-term effects of continuous intrathecal opioid treatment in chronic pain of nonmalignant etiology. J Neurosurg. 1996;85(3):458-467.

6 Follett KA, Boortz-Marx RL, Drake JM, et al. Prevention and management of intrathecal drug delivery and spinal cord stimulation system infections. Anesthesiology. 2004;100(6):1582-1594.

7 Paice JA, Penn RD, Shott S. Intraspinal morphine for chronic pain: a retrospective, multicenter study. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1996;11(2):71-80.

8 Aldrete JA, Couto DA, Silva JM. Leg edema from intrathecal opiate infusions. Eur J Pain. 2000;4(4):361-365.

9 Coffey RJ, Owens ML, Broste SK, et al. Mortality associated with implantation and management of intrathecal opioid drug infusion systems to treat noncancer pain. Anesthesiology. 2009;111(4):881-891.

10 Duse G, Davia G, White PF. Improvement in psychosocial outcomes in chronic pain patients receiving intrathecal morphine infusions. Anesth Analg. 2009;109(6):1981-1986.

11 Doleys D, Brown JL, Ness T. Multidimensional outcomes analysis of intrathecal, oral opioid, and behavioral-functional restoration therapy for failed back surgery syndrome: a retrospective study with 4 years’ follow-up. Neuromodulation. 2006;9(4):270-283.

12 Penn RD, Paice JA. Chronic intrathecal morphine for intractable pain. J Neurosurg. 1987;67(2):182-186.

13 Atli A, Theodore BR, Turk DC, Loeser JD. Intrathecal opioid therapy for chronic nonmalignant pain: a retrospective cohort study with 3-year follow-up. Pain Med. 2010;11(7):1010-1016.

14 Ilias W, le Polain B, Buchser E, Demartini L. oPTiMa study group: Patient-controlled analgesia in chronic pain patients: experience with a new device designed to be used with implanted programmable pumps. Pain Pract. 2008;8(3):164-170.

15 Ellis D, Dissanayake S, McGuire D, et al. Continuous intrathecal infusion of ziconotide for treatment of chronic malignant and nonmalignant pain over 12 months: a prospective, open-label study. Neuromodulation. 2008;11(1):40-49.

16 Shaladi A, Saltari MR, Piva B, et al. Continuous intrathecal morphine infusion in patients with vertebral fractures due to osteoporosis. Clin J Pain. 2007;23(6):511-517.

17 Deer T, Chapple I, Classen A, et al. Intrathecal drug delivery for treatment of chronic low back pain: report from the National Outcomes Registry for Low Back Pain. Pain Med. 2004;5(1):6-13.

18 Rauck RL, Cherry D, Boyer MF, et al. Long-term intrathecal opioid therapy with a patient-activated, implanted delivery system for the treatment of refractory cancer pain. J Pain. 2003;4(8):441-447.

19 Deer TR, Caraway DL, Kim CK, et al. Clinical experience with intrathecal bupivacaine in combination with opioid for the treatment of chronic pain related to failed back surgery syndrome and metastatic cancer pain of the spine. Spine J. 2002;2(4):274-278.

20 Smith TJ, Staats PS, Deer T, et al. Implantable Drug Delivery Systems Study Group: Randomized clinical trial of an implantable drug delivery system compared with comprehensive medical management for refractory cancer pain: impact on pain, drug-related toxicity, and survival. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20(19):4040-4049.

21 Rainov NG, Heidecke V, Burkert W. Long-term intrathecal infusion of drug combinations for chronic back and leg pain. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2001;22(4):862-871.

22 Becker R, Jakob D, Uhle EI, et al. The significance of intrathecal opioid therapy for the treatment of neuropathic cancer pain conditions. Stereotact Funct Neurosurg. 2000;75:16-26.

23 Roberts LJ, Finch PM, Goucke CR, Price LM. Outcome of intrathecal opioids in chronic non-cancer pain. Eur J Pain. 2001;5(4):353-361.

24 Anderson VC, Burchiel KJ. A prospective study of long-term intrathecal morphine in the management of chronic nonmalignant pain. Neurosurgery. 1999;44(2):289-300. discussion 300-301

25 Onofrio BM, Yaksh TL. Long-term pain relief produced by intrathecal morphine infusion in 53 patients. J Neurosurg. 1990;72(2):200-209.