Chapter 14 Complications of Gynaecological Surgery

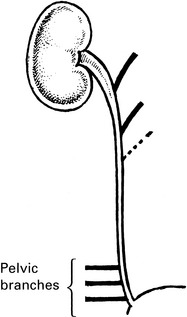

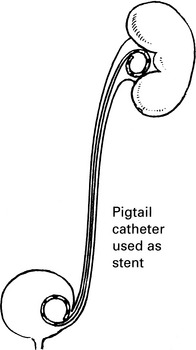

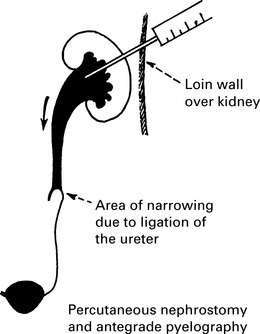

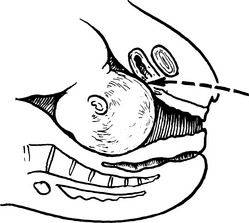

Management of ureteric injury

1. Types of ureteric injury identified at operation.

Fistula formation

Urinary fistula

Aetiology

1. The exposed bladder wall is torn or penetrated during a vaginal operation, or during total abdominal hysterectomy. This is the commonest cause in this country.

A tear develops during mobilisation of the bladder.

2. The vaginal wall and bladder are torn during an obstetric operation, or pressure necrosis develops during a prolonged and difficult labour.

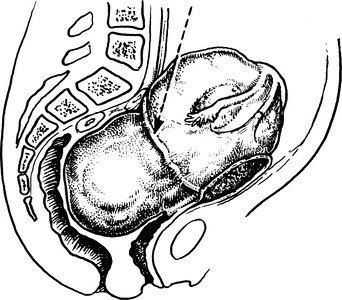

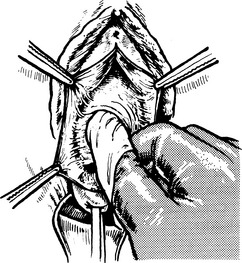

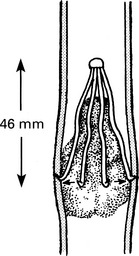

3. The ureter is damaged or made ischaemic during a pelvic operation, especially during radical hysterectomy. This produces a ureterovaginal fistula.Exposing ureter in radical hysterectomy

4. Radiation burns following treatment for carcinoma of the cervix. This fistula may appear several years after treatment.

5. Untreated or recurrent cancer of bladder or the genital tract. (This may also be complicated by radiation effects.)

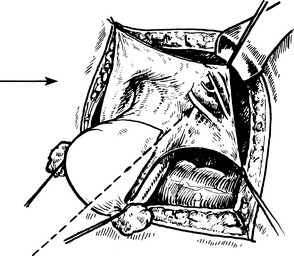

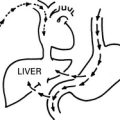

Lymphoedema and lymphocyst

Venous thrombosis

Risk factors for venous thrombosis

| Age | Exponential increase in risk with age. In the general population: <40 years annual risk 1/10,000 60–69 years annual risk 1/1000 >80 years annual risk 1/100 May reflect immobility and coagulation activation |

| Obesity | 3 × risk if obese (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2) May reflect immobility and coagulation activation |

| Varicose veins | 1.5 × risk after major general/orthopaedic surgery But low risk after varicose vein surgery |

| Previous VTE | Recurrence rate 5%/year, increased by surgery |

| Thrombophilias | Low coagulation inhibitors (antithrombin, protein C or S) Activated protein C resistance (e.g. Factor V Leidin) High coagulation factors (I, II, VIII, IX, XI) Antiphospholipid syndrome High homocysteine |

| Other thrombotic states | Malignancy 7 × risk Heart failure Recent myocardial infarction/stroke Severe infection Inflammatory bowel disease, nephrotic syndrome Polycythaemia, paraproteinaemia Bechet’s disease, paroxysmal nocturnal haemoglobinuria |

| Hormone therapy | Oral combined contraceptives, HRT, raloxifene, tamoxifen 3 × risk High dose progestogens 6× risk |

| Pregnancy, puerperium | 10 × risk |

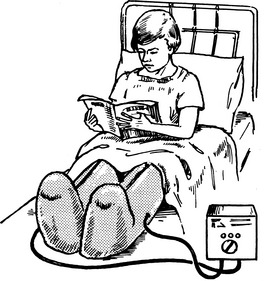

| Immobility | Bedrest >3 days 10× risk (increases with duration) |

| Hospitalisation | Acute trauma, acute illness, surgery, 10× risk |

| Anaesthesia | 2× general vs. spinal/epidural |

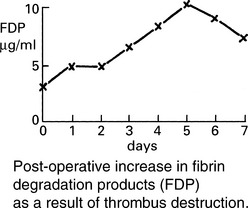

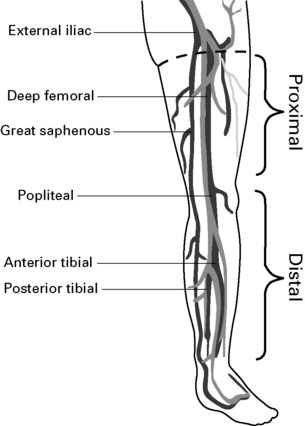

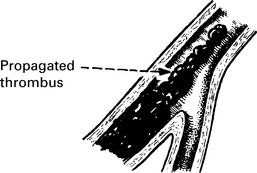

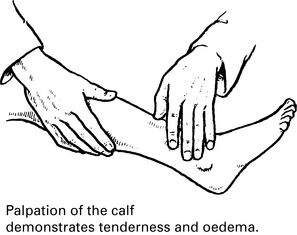

Pathology

Methods of thromboprophylaxis

General Measures

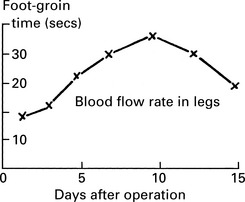

(1) Early ambulation – immobility increases the risk of DVT by about 10 fold and, hence, early mobilisation and leg exercises should be encouraged in postoperative patients.

Methods of thromboprophylaxis

Unfractionated and low molecular weight heparins

The risk of wound haematomas can be minimised by avoiding injection sites close to wounds.

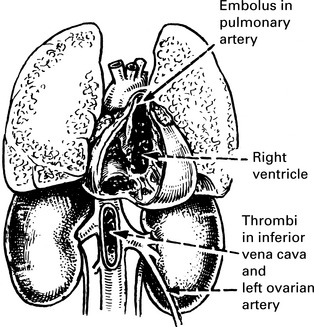

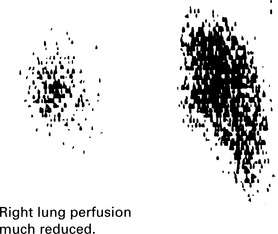

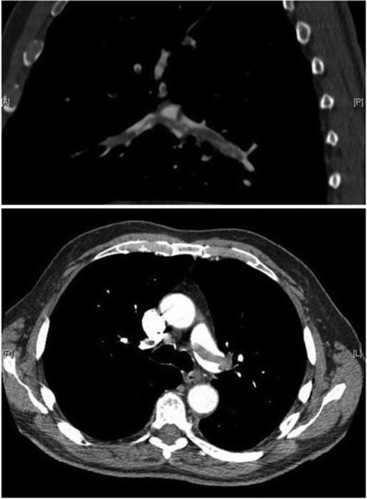

Pulmonary embolism

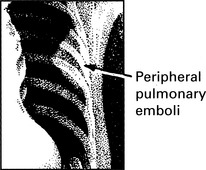

Peripheral pulmonary embolism

| Symptoms | Signs |

|---|---|

| Fever | Pyrexia |

| Tachypnoea | Pleural rub |

| Pleural pain | Crepitations |

| Haemoptysis (40%) | Perhaps opacity on lung X-ray |

Pulmonary embolism management

2. Suspect PE in all women presenting with a sudden onset of shortness of breath, chest pain, unexplained tachycardia or cardiovascular collapse.

4. Assess and ensure adequate airway, breathing and circulation. Commence cardiopulmonary resuscitation if the patient is in cardiac arrest.

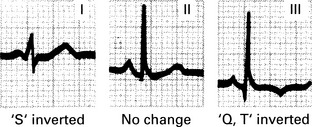

5. Transfer the patient to the high-dependency area when appropriate and commence monitoring: non-invasive blood pressure, pulse oximetry, ECG, urine output.