CHAPTER 40 Complications of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy

PREPARATION OF THE PATIENT FOR ENDOSCOPY

ANTIBIOTIC PROPHYLAXIS

A recognition of the increased risk for infections associated with certain endoscopic procedures and patient risk factors allows the use of prophylactic antibiotics in select situations (Table 40-1).1 These antibiotics are intended to prevent local complications such as cellulitis around a percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) tube site following its placement or infection of a pancreatic cyst following endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS)–guided fine-needle aspiration (FNA). Other infections may be the consequence of procedure-related bacteremia. Whereas patients with cardiac valve abnormalities may be at an increased risk for endocarditis from bacteremia, the role of prophylactic antibiotics for these patients has recently been reevaluated. The risk of endocarditis following endoscopy is very low and is likely less than the risk of endocarditis from ordinary daily activities such as teeth brushing. For these reasons, the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy and the American Heart Association no longer recommend routine use of prophylactic antibiotics prior to endoscopy.1,2

Table 40-1 Endoscopic Procedures for Which Antibiotic Prophylaxis Is Recommended*

| Upper Endoscopy |

| ERCP |

ERCP, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography; EUS-FNA, endoscopic ultrasonography–fine-needle aspiration; PEG, percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy.

* Antibiotics are not recommended for prevention of endocarditis and in patients with vascular grafts or prosthetic joints.

† Antibiotics recommended at time of hospital admission for all cirrhotic patients with gastrointestinal bleeding.

MANAGEMENT OF ANTICOAGULANT AND ANTIPLATELET DRUGS

Patients taking warfarin are at increased risks for bleeding following polypectomy, endoscopic sphincterotomy, balloon dilation, percutaneous gastrostomy, and EUS-FNA aspiration.3 Warfarin should be held before these procedures so that the prothrombin time (or international normalized ratio, INR) can return to normal and be restarted within 1 week after the procedure. In patients with mechanical heart valves and other situations at high risk for thromboembolism, use of unfractionated or low-molecular-weight heparin should be substituted for warfarin except during the 12 hours before and after the procedure.3–5

Drugs that affect platelet function such as aspirin, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, ticlopidine, clopidogrel, and other newer agents have not been clearly shown to increase bleeding complications from endoscopic procedures.3,5,6 Studies have been underpowered to detect small but potentially clinically significant effects on bleeding complication rates, however. The risk of bleeding following a specific procedure should be weighed against the risk of thromboembolic complications if antiplatelet therapy is discontinued in an individual patient.

INFORMED CONSENT

Written informed consent should be obtained before the performance of any endoscopic procedure.7 This consent should be obtained by the endoscopist personally and witnessed by another health care worker or family member whenever possible. The components of the informed consent process include a discussion of the benefits and alternatives to the procedure, as well as a discussion of the known risks of the procedure. The severity and frequency of complications influence the informed consent discussion; however, patient perception of risk is highly variable.8 The benefits and risks of sedation should always be included in the informed consent process if sedation is used. Written information about procedure-specific risks should be provided to the patient in advance of the procedure whenever possible.

COMPLICATIONS OF SEDATION

Sedation is used for most endoscopic procedures to allow a more comfortable experience for the patient and in some cases to allow a calm and still working environment for the endoscopist. Moderate (or conscious) sedation is used most commonly for GI endoscopy. By using a combination of a benzodiazepine and narcotic administered intravenously, the patient can be monitored by an assistant who is performing interruptible tasks.9 Deep sedation, usually achieved through the use of intravenous propofol, is being increasingly used in the United States, but risks are higher than with conscious sedation, and special monitoring and training are advisable. According to the ASA, deep sedation can be administered by non-anesthesiologists, but personnel who can rescue the patient from general anesthesia should be present.10

Several large series have demonstrated that propofol can be administered safely under the gastroenterologist’s supervision; however, additional training and monitoring with capnography are strongly recommended.11–14 Recovery times following propofol use are shorter than those following traditional conscious sedation with midazolam and fentanyl.15

Although most endoscopy can be performed safely under conscious sedation administered or supervised by the endoscopist, there are some situations in which having the assistance of an anesthesiologist or nurse anesthetist to administer deep sedation or general anesthesia can reduce the risk to the patient.16 Patients with a history of being difficult to sedate may benefit from deep sedation. This often includes alcoholic patients and those who are on high doses of narcotics. Patients with hemodynamic instability and respiratory compromise should also have special monitoring of sedative drug use.

Cardiorespiratory complications, usually attributed to sedation, are the most common complications of GI endoscopy. Survey data suggest that approximately half of endoscopic complications are in this category.17,18 The reported frequency of cardiac and respiratory complications of endoscopy is between 2 and 5 per 1000 procedures with approximately 10% of these complications resulting in death.19 Cardiopulmonary complications as high as 11 per 1000 procedures have been reported with propofol-mediated sedation.20

Respiratory complications of sedation are most commonly due to hypoventilation. Combinations of benzodiazepine and narcotics are known to produce more respiratory depression than use of either agent alone. The routine use of pulse oximetry allows more judicious titration of sedative medications but does not detect significant hypercarbia.21 The latter can be detected with capnography,22 but this is still not used routinely in most endoscopic facilities. Airway assessment is also important before endoscopy for the safety of the upper endoscopic procedure and for the ability to provide respiratory support should hypoventilation occur. Risk factors for airway compromise include difficulties with previous anesthesia or sedation, obesity, a small mouth or lower jaw, and a history of stridor or sleep apnea.9,10

Hypotension is also usually due to medications. Narcotics in particular cause peripheral venous dilation and reduced cardiac preload, which in the fasting volume-depleted patient can lead to significant hypotension. This problem is usually responsive to intravenous fluid boluses, reason enough to require intravenous access during endoscopy done with sedation.9

Vasovagal reactions are the most common cause of cardiac arrhythmia during endoscopy. These reactions have been reported to occur in 16% of colonoscopies but can also occur with endoscopy of the upper GI tract.23,24 Reducing painful stimuli and suctioning air from the bowel are generally sufficient to reverse the vagally mediated bradycardia and hypotension; however, reversal with atropine is required for persistent bradycardia with hypotension in approximately one third of cases.23 Self-limited ventricular arrhythmias may be seen in up to 20% of older adult patients undergoing upper endoscopy, particularly if they have electrocardiographic changes suggesting ischemia.25

Careful monitoring of the patient during endoscopy helps detect cardiorespiratory complications at an early stage so that specific action can be taken. Observation of the patient by a qualified assistant who is not actively involved in performing the procedure can detect apnea and loss of consciousness.9 Intermittent blood pressure readings and continuous pulse oximetry are useful adjuncts and are recommended for patients receiving sedation.9,26 Although continuous monitoring of the electrocardiogram is also advisable for patients with a history of cardiac arrhythmias, routine monitoring of the electrocardiogram is not required for all patients.

The endoscopist should be familiar with specific side effects of the medications used for sedation during endoscopy (Table 40-2). In addition to commonly used benzodiazepines and narcotics, other drugs are sometimes used to augment sedation. Reversal agents for benzodiazepines (flumazenil) and narcotics (naloxone) are useful agents when oversedation occurs.

Table 40-2 Side Effects of Medications Used for Sedation, Analgesia, and Reversal

| AGENT | COMMON SIDE EFFECTS OF CLASS | AGENT-SPECIFIC SIDE EFFECTS |

|---|---|---|

| Benzodiazepines | Respiratory depression, hypotension, cardiac arrhythmias, headache, confusion, nystagmus | |

| Diazepam | Phlebitis and thrombosis at IV site | |

| Midazolam | Amnesia | |

| Narcotics (Opiates) | Respiratory depression, hypotension, urinary retention | |

| Meperidine | Myoclonus, seizures, nausea and vomiting | |

| Fentanyl | ||

| Topical Anesthetics | Hypersensitivity reactions, methemoglobinemia | |

| Lidocaine | ||

| Benzocaine | ||

| Miscellaneous Agents | ||

| Propofol | Respiratory depression and arrest, hypotension, bradycardia, hyperlipidemia | |

| Droperidol | Sedation, extrapyramidal effects, prolonged QT interval, cardiac arrest | |

| Diphenhydramine | Sedation, nausea, dry mouth | |

| Promethazine | Sedation, orthostatic hypotension, extrapyramidal effects, hemolytic anemia | |

| Reversal Agents | ||

| Flumazenil* | Vasodilation, headache, seizures | |

| Naloxone† | Hypotension, cardiac arrhythmias, narcotic withdrawal |

IV, intravenous.

* Reverses effects of benzodiazepines.

† Reverses effects of opiate narcotics.

Patients should be observed in the endoscopy unit following a procedure until they are conscious and their vital signs have returned to baseline.9,10 Scales are available to assist staff in objectively quantifying discharge criteria.27 Because sedating medications can have subtle effects on higher level mental functions for hours after administration, it is advisable to have the patient accompanied by another individual on discharge and to recommend that the patient not drive or operate machinery until the day following the procedure.9

INFECTIOUS COMPLICATIONS

Infections such as with Pseudomonas species or hepatitis C can be introduced by the endoscope, and are not specific to the procedure type or the patient’s underlying disease. Whereas these exogenous infections are infrequent, they merit discussion because they are usually avoidable.28 Current endoscopes are highly specialized and expensive pieces of equipment that are designed to be reused. Because the GI tract is not sterile, high-level disinfection between uses is deemed to be sufficient for preventing transmission of infectious organisms between patients.29,30 The process of high-level disinfection includes mechanical cleaning of the working channels and exterior of the endoscope, followed by soaking in disinfectant solutions such as glutaraldehyde or orthophthalaldehyde, and then thorough rinsing and drying of the instruments.

Most instances of documented transmission of infection can be traced to a failure in one of the recommended steps of endoscope reprocessing.28,30,31 The estimated prevalence of transmission of infectious organisms by endoscopes is 1 in 1.8 million procedures.30,31 This number may underestimate the frequency of this problem, however, because some infections may not be detected or reported. Prospective studies have not demonstrated transmission of hepatitis C by properly performed gastrointestinal endoscopy.32,33

High-level disinfection kills most viruses and bacteria that could contaminate endoscopes. Common blood-borne pathogens such as human immunodeficiency virus and hepatitis B and C viruses are readily inactivated by the high-level disinfection process. Although prions such as the Jakob-Creutzfeldt agent may not be inactivated by high-level disinfection, transmission of these agents by endoscopy has not been reported.28

Infectious organisms may also be transmitted by endoscopic accessories or by contaminated needles and drugs used for sedation. Most endoscopic accessories are designed for single use and should be discarded following use. Reusable accessories should be sterilized after use to avoid transmitting infectious organisms.29 Outbreaks of hepatitis C following endoscopy have been traced to improper sterile technique and contamination of multidose vials of sedative medications. Sterile single-use needles and intravenous tubing should always be used. Unused medication should be discarded after each procedure, and use of multidose medication vials should be discouraged.

OTHER GENERAL COMPLICATIONS

ELECTROSURGERY

Electrosurgical generators are reliable devices that have long useful lives. Routine electrical maintenance and safety checks are mandatory, however. Operator error can be reduced by familiarity with the equipment being used. A large number and variety of electrosurgical generators exist, and they differ in their effect on tissue even with the same energy settings.34 The dispersive electrode or ground pad should be placed in firm contact with a large skin surface to avoid skin burns.

Electrosurgery with monopolar devices causes a spark of energy when the device is activated. If sufficient concentrations of explosive gases are present, the spark may trigger an explosion. This has been reported when electrosurgery has been performed in the poorly prepared colon or following mannitol-containing laxatives in which high concentrations of hydrogen and methane may be present.35

MISCELLANEOUS COMPLICATIONS

Although the prevalence of minor complications of endoscopy has not been well established, these problems should not be trivialized. Sore throats after upper endoscopy, pain, infections or phlebitis at intravenous catheter sites, and prolonged recovery from the effects of sedation can affect a patient’s quality of life.36

TIMING AND SEVERITY OF COMPLICATIONS

Delayed procedural complications can be caused by late occurrence of the problem or the delayed presentation or recognition of an early complication. For example, bleeding from a colonic ulcer after polypectomy may not occur until one to two weeks after colonoscopy.37 Asking the patient to watch for bloody or melenic stools and to inform the endoscopist promptly should they occur should be part of the postprocedure discharge instructions. Attributing abdominal distention to intracolonic air after a colonoscopy and not suspecting colonic perforation may lead to delayed recognition of an immediate life-threatening complication.

MEDICOLEGAL CONSIDERATIONS

Complications of endoscopy are one of the most frequent causes of malpractice suits against gastroenterologists.38 Malpractice can occur if the physician does not meet his or her obligation to the patient or if the care provided does not meet the standard of care. The occurrence of a complication does not mean malpractice was committed if the procedure was properly performed and the patient was informed of potential complications of the procedure.

COMPLICATIONS OF UPPER ENDOSCOPY

RESPIRATORY PROBLEMS

It is remarkable that respiratory complications of upper endoscopy are infrequent, given that the endoscope is passed through the oropharynx. Stridor, reflecting upper airway compromise, occurs rarely during endoscopy, usually in patients with small upper airways due to congenital anomalies, prior surgery, or radiation. Use of small-caliber endoscopes in selected patients may help reduce this problem. Patients with neuromuscular weakness such as occurs with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis may also have symptoms and signs of upper airway obstruction during endoscopy. Nasal administration of positive-pressure ventilation during upper endoscopy may increase procedural safety in these patients.39

Aspiration pneumonia is another complication of upper endoscopy that occurs in approximately 1 in 10,000 procedures.17 Careful attention to oral suctioning and selective use of endotracheal intubation for endoscopy in at-risk patients such as the obtunded patient with upper GI bleeding may reduce this complication. Elective endotracheal intubation of patients with suspected variceal hemorrhage who are not encephalopathic may increase the risk of aspiration pneumonia, however.40

COMPLICATIONS OF TOPICAL ANESTHESIA

Topical anesthesia is commonly used during upper endoscopy to ease the performance of endoscopy and improve patient tolerance.41 Lidocaine and especially benzocaine sprays very rarely cause methemoglobinemia, which should be considered when oxygen saturation detected by pulse oximetry falls during or following an endoscopy in which topical anesthesia was administered.42,43 Clues to methemoglobinemia are a normal respiratory rate and arterial oxygen content (Po2) despite clinical cyanosis and low oxygen saturation on pulse oximetry. The condition can be fatal but is reversible after intravenous administration of methylene blue.

HEMORRHAGE

Bleeding complications of upper endoscopy are most commonly seen during therapeutic procedures such as dilation or enteral access procedures (see later). Bleeding caused by passage of the endoscope through the oropharynx or from a Mallory-Weiss tear at the gastroesophageal junction has been reported but is rare44,45 and usually stops spontaneously unless the patient has a coagulopathy. Bleeding from mucosal biopsies, even when a large cup forceps is used, is also infrequent but can lead to either intraluminal hemorrhage or intramural hematomas.46 Biopsies should not be done in patients with significant prolongations in the prothrombin time (INR >2) or with severe thrombocytopenia (<20,000).17,44

PERFORATION

Perforation of the upper GI tract during diagnostic endoscopy has been estimated to occur in 3 to 5 out of 10,000 procedures and is usually associated with therapeutic as opposed to diagnostic procedures.17,47 The most common site of perforation from upper endoscopy is in the oropharynx or cervical esophagus. Patients with Zenker’s diverticula, proximal esophageal strictures and cancers, and those with large cervical osteophytes are at increased risk of perforation. The presence of crepitus in the neck soft tissues, fever, and chest or neck pain following endoscopy should prompt an investigation for perforation with chest and neck radiographs; a pharyngoesophagogram with water-soluble contrast; and, if necessary, neck and chest computed tomography (CT) scan. Pharyngeal perforations that are not recognized at the time of endoscopy may manifest after a few days or weeks with a retropharyngeal abscess, which should be drained surgically.

Most perforations within the neck can be managed conservatively in conjunction with an otolaryngologist and use of broad-spectrum intravenous antibiotics. Intrathoracic perforations can also be managed conservatively with antibiotics and nasoesophageal suction if the perforation is small and contained to the tissues immediately surrounding the esophagus. When there is communication with the pleural space, thoracotomy is usually recommended. The recent availability of removable polyethylene esophageal stents may change this recommendation, especially in patients with malignancy or increased risks for surgery because placement of this type of stent may allow esophageal perforations to seal without surgery.48

COMPLICATIONS OF DILATION

Dilation anywhere in the GI tract increases the risk of complications compared with diagnostic endoscopy. The greatest risk is perforation, with significant bleeding being much less common. The type of dilator used, whether a guidewire bougie or through the scope balloon, does not appear to significantly affect risk.49 Malignant, radiation-induced, and lye strictures in the esophagus are more likely to perforate than peptic strictures. Balloon dilation of pyloric and duodenal strictures appears to carry a greater risk of perforation than dilation of strictures at surgical anastomoses. Although never proved, the practice of gradual dilation over multiple endoscopic sessions may carry a lower risk of perforation. Strictures should be dilated to a diameter that results in symptom resolution, and not necessarily to the size of the uninvolved lumen. Cerebral air embolism complicated by stroke and seizure has been reported following esophageal dilation and other endoscopic procedures.50

COMPLICATIONS OF ENDOSCOPIC HEMOSTASIS

Multipolar and heater probe therapy of bleeding peptic ulcers carries a risk of perforation of approximately 1%.51 This risk increases to 4% when a second treatment session is required within 48 hours for hemostasis of recurrent bleeding.52 Injection therapy with epinephrine can cause tachycardia and in some cases ischemic ulceration at the site of injection (see Chapters 10 and 53).

Variceal sclerotherapy has been largely replaced by variceal band ligation because of similar efficacy but fewer complications with ligation (see Chapter 90). Sclerotherapy causes esophageal ulcerations that can bleed significantly in 6% of patients and lead to delayed esophageal strictures in up to 20% of patients.53 Other complications of sclerotherapy include esophageal perforation in 2% to 5% of patients, pleural and pericardial effusions, mediastinitis, and paralysis.54 These complications carry a high mortality, largely because of the presence of severe underlying liver disease in these patients. Band ligation leads to fewer ulcerations and delayed strictures than sclerotherapy and perforation in less than 1% of cases.53,55

COMPLICATIONS OF ENTERAL ACCESS PROCEDURES

Endoscopy is used to place a variety of tubes into the upper GI tract for the delivery of enteral nutrition (see Chapter 5). Endoscopic nasoenteric tube placement ensures delivery of the feeding tube into the small intestine and is associated with usually minor, self-limited complications in 10% of cases.56 Epistaxis is the most common complication, occurring in 2% to 5%. Proximal migration out of the small intestine occurs in 15%, and tube clogging in up to 20% of cases.57

PEG involves direct puncture of the stomach, through the abdominal wall, under endoscopic control (see Chapter 5). Complications occur in 1.5% to 4% of procedures.57 The most frequent complication of this procedure is infection at the site of tube entry, which occurs in up to 30% of cases. These infections are usually minor and can be treated with antibiotics but can occasionally be severe and lead to necrotizing fasciitis that requires surgical débridement. As mentioned, preprocedure antibiotics have been shown to reduce the frequency of minor wound infections after PEG placement.58,59

Bleeding during PEG placement is usually minor and self-limited but can require endoscopic hemostasis in 1% of cases, usually as a result of puncture of an artery in the gastric wall.60 Other rare complications of PEG procedures include premature tube dislodgment that can lead to peritonitis and inadvertent puncture of the liver and colon, the latter leading to formation of a gastrocolic fistula. The “buried bumper syndrome” occurs when the external bolster of the PEG tube remains too tight and causes migration of the internal bolster (or bumper) into the gastric wall.61 When PEG tubes are placed in patients with head and neck or esophageal cancer, seeding of the PEG site with tumor implants may rarely occur by either local or hematogenous routes.62,63

Aspiration pneumonia in patients receiving enteral feedings can be either due to aspiration of oropharyngeal bacteria or from gastroesophageal reflux of enteral feedings. The former mechanism is probably more common.64 However, GE reflux can be responsible for pneumonia, especially in patients with a history of documented aspiration, overt vomiting or regurgitation, reduced level of consciousness, neuromuscular or structural problems of the oropharynx, prolonged supine position, and high gastric residual volumes.64

Placement of feeding tubes directly into the proximal jejunum is being increasingly performed. Complications are similar to those of PEG, with the addition of rare cases of small bowel obstruction that can be caused by large internal bolsters or small intestinal volvulus.65

COMPLICATIONS OF OTHER THERAPEUTIC PROCEDURES

Expandable metal stents are used to treat malignant esophageal strictures (see Chapter 46) and are associated with complications in approximately 10% to 20% of cases.66 Perforation, chest pain, and gastroesophageal reflux are the most common complications. Delayed complications include distal or proximal migration and food impaction.

Endoscopic removal of foreign bodies from the upper GI tract (see Chapter 25) is associated with complications in up to 8% of cases.67 Aspiration pneumonia, bleeding, and esophageal perforation can be avoided by attention to guidelines on the types of foreign bodies that should be removed endoscopically and the timing of the intervention.68

COMPLICATIONS OF SMALL BOWEL ENDOSCOPY

DOUBLE BALLOON ENTEROSCOPY

Double balloon enteroscopy is a new technique for visualization of larger extents of the small bowel by using sequentially inflated balloons on the shaft of the endoscope and an accompanying overtube. The endoscope has a channel that allows application of therapeutic techniques such as polypectomy, injection, and thermal coagulation. As with upper endoscopy, complication rates are higher with therapeutic procedures (4%) compared with diagnostic procedures (1%).69 An unexpected complication of double balloon enteroscopy is acute pancreatitis. This has been reported in about 1 in 500 procedures and is hypothesized to be due to increased intraluminal pressures in the duodenum between the inflated balloons on the endoscope and overtube.69,70

CAPSULE ENDOSCOPY

The primary complication of capsule endoscopy is retention of the capsule above an unsuspected small intestinal stricture. This occurs in 1% to 2% of capsule procedures.71 These strictures can be quite focal and not detected by small intestinal radiography. A dissolvable, radiopaque, radiofrequency emitting capsule has been proposed for detecting small bowel strictures prior to capsule ingestion.72 Other rare complications of capsule endoscopy include aspiration of the capsule into the trachea.73

COMPLICATIONS OF COLONOSCOPY AND SIGMOIDOSCOPY

The overall risk of complications of diagnostic colonoscopy is approximately 0.3%.74–78 The risk is higher (2%) when polypectomy is performed. The main complications of colonoscopy are perforation, bleeding, and postpolypectomy syndrome. Colon preparation regimens can also cause complications in some patient populations (see later). The risks of sigmoidoscopy are approximately two-fold lower than colonoscopy but include the same types of complications seen with colonoscopy.79

HEMORRHAGE

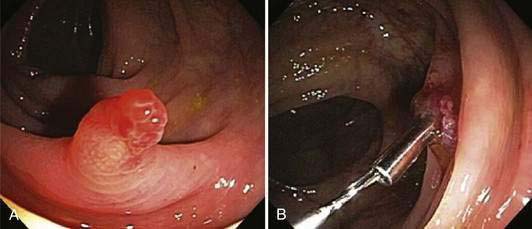

The most common cause of bleeding during or following colonoscopy is a polypectomy. This occurs in approximately 1.5% to 3% of patients undergoing polypectomies, with approximately an equal distribution of immediate and delayed bleeding.80 Delayed bleeding usually occurs within two weeks following polypectomy and is more common when large polyps are removed in patients with uncontrolled hypertension.37 Immediate bleeding usually can be stopped at the time of colonoscopy by holding a snare around a polyp stalk for five minutes, injecting dilute epinephrine solution, or placing a hemostatic clip on the bleeding vessel (Fig. 40-1). Delayed bleeding is best diagnosed by repeat colonoscopy, which allows treatment using the same modalities that are used with immediate bleeding.

Delayed bleeding also can occur from causes other than polypectomy. Ulcerations caused by treatment of angioectasia in the colon with argon plasma coagulation or multipolar probes can bleed (Fig. 40-2; also see Chapters 19 and 36). Biopsy sites are rare sources of bleeding following colonoscopy, even when multiple biopsies are taken during surveillance for dysplasia in patients with inflammatory bowel disease.81

PERFORATION

Colonic perforation is the most feared complication of colonoscopy but is fortunately infrequent, occurring in 0.1% to 0.9% of colonoscopies.75–7982 Polypectomy approximately doubles the risk of perforation over the background perforation rate with diagnostic colonoscopy.77

Perforations can be caused by excessive air pressure (barotrauma), by tearing of the antimesenteric border of the colon from excessive pressure on colonic loops, and at the sites of electrosurgical applications. Barotrauma occurs most often in the cecum, where colonic diameter is greatest and therefore tension on the colonic wall is highest. Colonic tears occur most frequently in the sigmoid colon, where loops are most frequent. Large tears can sometimes be recognized during the colonoscopy and should lead to immediate operative intervention (Fig. 40-3). Perforation can also occur at polypectomy sites or following the application of argon plasma coagulation or thermal probes for the treatment of bleeding diverticula or angioectasia.83

Figure 40-3. Pericolonic fat is seen through the wall of the sigmoid colon, which was perforated during colonoscopy.

Other uses of colonoscopy as a treatment modality also increase the risk of colonic perforation. Colonoscopic decompression of acute colonic pseudo-obstruction (see Chapter 120) is associated with perforation in 2% of cases.84 Placement of colonic stents to relieve malignant obstruction (see Chapter 123) may cause perforation in up to 5% of cases.85 Balloon dilation of colonic strictures in patients with Crohn’s disease (see Chapter 111) carries a 10% risk of perforation.86

Treatment of colonoscopic perforation depends on the severity of the perforation and the condition of the patient. Large tears and patients with signs of peritonitis require operative treatment. Earlier detection may allow primary repair without formation of a colostomy. Stable patients with microperforations caused by barotrauma or electrocautery can sometimes be managed without surgery with bowel rest and parenteral antibiotics.87,88 Careful observation of the patient by the physician in conjunction with a surgeon is advisable in this situation.

POSTPOLYPECTOMY COAGULATION SYNDROME

Full-thickness electrosurgical burns following polypectomy may cause localized abdominal pain, fever, and leukocytosis without free intra-abdominal air on imaging studies. Localized peritoneal signs may be present. Patients usually present from 1 to 5 days following colonoscopy, and symptoms resolve in 2 to 5 days.89 Management depends on the severity of symptoms. Patients with mild pain and little fever can be managed with oral antibiotics as outpatients. Patients with more severe pain and fever should be observed in the hospital with bowel rest, intravenous antibiotics, and frequent physical examinations and radiographs to detect perforation.90

COMPLICATIONS RELATED TO COLON PREPARATION

Oral administration of sodium phosphate and polyethylene glycol electrolyte solutions to clean the colon before colonoscopy can cause problems in susceptible patients. Hyperphosphatemia, hypocalcemia, and acute kidney injury are most likely to occur with sodium phosphate preparations in patients with renal insufficiency, older adults, and patients taking angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers.91–94 Sodium phosphate solutions can cause intravascular volume depletion in patients with congestive heart failure, acute kidney injury, and cirrhosis. Polyethylene glycol–containing solutions are better tolerated in these situations but may also cause fluid shifts; patients with severe underlying diseases should have a more gradual bowel preparation and be monitored closely.95,96

OTHER COMPLICATIONS

Other rare complications of colonoscopy include splenic rupture or hemorrhage, intra-abdominal bleeding caused by mesenteric vessel rupture, and acute appendicitis.97 Chemical colitis due to inadequate rinsing of disinfectant solutions has been reported.98 Death from colonoscopy is rare, occurring in less than 1 in 16,000 procedures.90

COMPLICATIONS OF ERCP

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) is one of the most rewarding endoscopic procedures but also is one of the most dangerous. Appropriate training, adequate ongoing experience, and good clinical judgment are requisites to avoiding complications.99 A striking observation about post-ERCP complications is that the patients who are at the highest risk for complications, and especially the more severe complications, are the ones who are least likely to benefit from the procedure.100,101

PANCREATITIS

The most common complication of ERCP is acute pancreatitis (see Chapter 58), which occurs in 2% to 25% of cases.101–103 The risk factors for post-ERCP pancreatitis have been well defined and include patient and procedural factors (Table 40-3).101,104,105 Pancreatitis severity can range from mild, resulting in two to three days of hospitalization, to severe, requiring surgery or even causing death.

| PATIENT FACTORS | PROCEDURAL FACTORS |

|---|---|

| Young age | Number of injection attempts |

| Female gender | Pancreatic duct injection |

| Suspected sphincter of Oddi dysfunction | Pancreatic sphincterotomyBalloon dilation of biliary sphincter |

| Previous post-ERCP pancreatitis | Difficult or failed cannulationPrecut sphincterotomy |

| Recurrent pancreatitis |

ERCP, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography.

From Freeman ML, Guda NM: Prevention of post-ERCP pancreatitis: A comprehensive review. Gastrointest Endosc 2004; 59:845.

Pharmacologic approaches to preventing post-ERCP pancreatitis have been disappointing.105 Using alternative imaging techniques such as magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) or endoscopic ultrasonography in patients with a low probability of requiring endoscopic therapy may be the best way to avoid this complication. When ERCP is performed in high-risk patients such as a young woman with a small bile duct and suspected sphincter of Oddi dysfunction, placing a temporary pancreatic stent can significantly reduce the risk of post-ERCP pancreatitis.106,107 Whether the use of pure cutting current for sphincterotomy reduces the risk of post-ERCP pancreatitis is controversial.108–110

Treatment of post-ERCP pancreatitis is supportive and similar to treatment of other causes of acute pancreatitis (see Chapter 58). There is no established role for repeat ERCP or pancreatic stenting in this setting.

HEMORRHAGE

Bleeding complications of ERCP are usually secondary to sphincterotomy and occur in 1% to 2% of cases.100,102,103 Risk factors for postsphincterotomy bleeding include coagulopathy, use of anticoagulants within 72 hours following the procedure, cholangitis, precut sphincterotomy, and low case volume of the endoscopist.100 Bleeding seen at the time of the sphincterotomy is also predictive of delayed bleeding and should be treated aggressively.

Treatment of delayed postsphincterotomy hemorrhage initially should be directed at transfusion of blood products and correction of coagulopathy. Repeat endoscopy with use of epinephrine injection, thermal probes, and hemostatic clips is effective for stopping bleeding in most cases.111 When endoscopic therapy fails, angiographic therapy or surgery should be considered depending on the condition and comorbidities of the patient.

PERFORATION

Another complication of ERCP is perforation of the upper GI or biliary tract. This occurs in approximately 0.5% of cases and can be caused by guidewires, periampullary perforation from sphincterotomy, or the endoscope at sites remote from the ampulla.112 Guidewire perforations generally occur in the biliary tree and usually do not create significant bile leaks if distal obstruction is relieved with sphincterotomy or biliary stenting. Perforations remote from the ampulla are often large and require surgical repair. These perforations should be suspected in patients with marked abdominal pain and distention following ERCP and diagnosed with upright abdominal and chest radiographs.

Periampullary perforations are usually contained to the retroperitoneum surrounding the ampulla and can be diagnosed with abdominal CT scan. If recognized promptly, the majority can be treated with nasogastric suction and intravenous antibiotics.113 Percutaneous or surgical drainage is required if CT scan documents an enlarging abscess despite conservative therapy.

CHOLANGITIS

Ascending cholangitis following ERCP occurs in less than 1% of cases and is usually caused by injecting contrast into an obstructed biliary tree and then not providing adequate biliary drainage by removing all stones or placing a biliary stent.102,114 Patients with complex biliary strictures at the hepatic hilum due to cholangiocarcinoma have an increased risk of cholangitis. Care should be taken to inject contrast only into bile ducts that can be subsequently drained with a stent.115 Prophylactic antibiotics have not been shown to reduce the risk of cholangitis following ERCP116,117 and their use is declining.118 Current guidelines recommend prophylactic antibiotics only for patients with biliary obstruction when it is anticipated that drainage might be incomplete (see Table 40-1).1

OTHER COMPLICATIONS

Acute cholecystitis occurs in less than 0.5% of ERCPs. Cystic duct obstruction by gallbladder stones and bile duct stents that occlude the cystic duct orifice are the usual causes. Pancreatic infection can also occur in up to 8% of cases when contrast is injected into obstructed pancreatic ducts or pseudocysts and drainage is not provided.119 A plan for pseudocyst drainage, either endoscopic, percutaneous, or surgical, should always be made before undertaking ERCP in patients with a known pancreatic pseudocyst (see Chapter 61).120,121

COMPLICATIONS OF ENDOSCOPIC ULTRASONOGRAPHY

Diagnostic EUS carries the same risks of sedation, bleeding, and perforation as diagnostic endoscopy. The frequency of complications related to EUS has been reported to be from 0.1% to 0.3%.122,123 The addition of medical ultrasound carries no additional known risks to the patient. Because most ultrasound endoscopes are forward oblique viewing rather than forward viewing, care must be taken in passing the endoscope through the oropharynx and strictures.124 The risk of perforation of malignant esophageal strictures was as high as 24% with older endoscopes that were larger and had a blunt tip. Perforation using current instruments is much less common. It is advisable to serially dilate tight esophageal strictures before EUS or to use special small-caliber, wire-guided instruments in this setting.125

COMPLICATIONS OF FINE-NEEDLE ASPIRATION

The addition of FNA to EUS has introduced the potential for additional complications of hemorrhage, infection, and pancreatitis. Bleeding due to EUS-FNA is rare but can be lethal if a major vessel is lacerated.126 This complication has not been reported with linear array ultrasonography endoscopes that are used for FNA, however.

Infection is primarily a risk when pancreatic or mediastinal cysts are aspirated. This has been reported to occur in up to 14% of cases.127 The use of prophylactic antibiotics and aspiration of all fluid from the cyst with one pass of the needle have been advocated as ways to reduce the risk of infection.128 Prophylactic antibiotics are not recommended prior to FNA of solid lesions because bacteremia is rare, even following lower GI tract procedures.129

Pancreatitis following EUS-FNA of the pancreas has been reported in less than 1% of cases.130 Care should be taken to find a needle path away from the main pancreatic duct when undertaking FNA of a pancreatic lesion.

American Society of Anesthesiologists. Task Force on Sedation and Analgesia by Non-Anesthesiologists. Practice guidelines for sedation and analgesia by non-anesthesiologists. Anesthesiology. 2002;96:1004-17. (Ref 10.)

American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. Guideline on the management of low-molecular-weight heparin and nonaspirin antiplatelet agents for endoscopic procedures. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61:189-94. (Ref 5.)

American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. Guideline on antibiotic prophylaxis for GI endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;67:791-8. (Ref 1.)

American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. Guideline on infection control during GI endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;67:781-90. (Ref 30.)

Ciancio A, Manzini P, Castagno F, et al. Digestive endoscopy is not a major risk factor for transmitting hepatitis C virus. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142:903-9. (Ref 32.)

Cobb WS, Heniford T, Sigmon LB, et al. Colonoscopic perforations: incidence, management, and outcomes. Am Surg. 2004;70:750-8. (Ref 88.)

Cotton PB, Connor P, Rawls E, Romagnuolo J. Infection after ERCP, and antibiotic prophylaxis: a sequential quality-improvement approach over 11 years. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;67:471-5. (Ref 118.)

Evans LT, Saberi S, Kim HM, et al. Pharyngeal anesthesia during sedated EGDs: Is “the spray” beneficial? A meta-analysis and systematic review. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63:761-6. (Ref 41.)

Freeman ML, Nelson DB, Sherman S, et al. Complications of endoscopic biliary sphincterotomy. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:909-18. (Ref 100.)

Khurana A, McLean L, Atkinson S, Foulks CJ. The effect of oral sodium phosphate drug products on renal function in adults undergoing bowel endoscopy. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:565-7. (Ref 94.)

Ko CW, Riffle S, Shapiro JA, et al. Incidence of minor complications and time lost from normal activities after screening or surveillance colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;65:648-56. (Ref 36.)

Levin TR, Zhao W, Conell C, et al. Complications of colonoscopy in an integrated health care delivery system. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145:880-6. (Ref 77.)

McClave SA, Chang W-K. Complications of enteral access. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58:739-51. (Ref 57.)

Qadeer MA, Vargo JJ, Khandwala F, et al. Propofol versus traditional sedative agents for gastrointestinal endoscopy: A meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;3:1049-56. (Ref 14.)

Tarnasky PR, Palesch YK, Cunningham JT, et al. Pancreatic stenting prevents pancreatitis after biliary sphincterotomy in patients with sphincter of Oddi dysfunction. Gastroenterology. 1998;115:1518-24. (Ref 106.)

1. American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. Guideline on antibiotic prophylaxis for GI endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;67:791-8.

2. American College of Cardiology. ACC/AHA 2008 guideline update on valvular heart disease: focused update on infective endocarditis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52:676-85.

3. American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. Guideline on the management of anti-coagulation and anti-platelet therapy for endoscopic procedures. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;55:775-9.

4. Jafri SM. Periprocedural thromboprophylaxis in patients receiving chronic anticoagulation therapy. Am Heart J. 2004;147:3-15.

5. American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. Guideline on the management of low-molecular-weight heparin and nonaspirin antiplatelet agents for endoscopic procedures. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61:189-94.

6. Yousfi M, Gostout CJ, Baron TH, et al. Postpolypectomy lower gastrointestinal bleeding: Potential role of aspirin. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:1785-9.

7. American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. Guideline on informed consent for GI endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66:213-18.

8. Brooks AJ, Hurlstone DP, Fotheringham J, et al. Information required to provide informed consent for endoscopy: An observational study of patients’ expectations. Endoscopy. 2005;37:1136-9.

9. American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. Guidelines for conscious sedation and monitoring during gastrointestinal endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58:317-22.

10. American Society of Anesthesiologists. Task Force on Sedation and Analgesia by Non-Anesthesiologists. Practice guidelines for sedation and analgesia by non-anesthesiologists. Anesthesiology. 2002;96:1004-17.

11. Vargo JJ, Zuccaro GJr, Dumot JA, et al. Gastroenterologist-administered propofol versus meperidine and midazolam for advanced upper endoscopy: A prospective, randomized trial. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:8-16.

12. Rex DK, Overley C, Kinser K, et al. Safety of propofol administered by registered nurses with gastroenterologist supervision in 2000 endoscopic cases. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:1159-63.

13. Heuss LT, Schnieper P, Drewe J, et al. Risk stratification and safe administration of propofol by registered nurses supervised by the gastroenterologist: A prospective observational study of more than 2000 cases. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;57:664-71.

14. Qadeer MA, Vargo JJ, Khandwala F, et al. Propofol versus traditional sedative agents for gastrointestinal endoscopy: A meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;3:1049-56.

15. Mandel JE, Tanner JW, Lichtenstein GR, et al. A randomized, controlled, double-blind trial of patient-controlled sedation with propofol/remifentanil versus midazolam/fentanyl for colonoscopy. Amb Anesthes. 2008;106:434-9.

16. American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. Guidelines for the use of deep sedation and anesthesia for gastrointestinal endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:613-17.

17. Silvis SE, Nebel O, Rogers G, et al. Endoscopic complications: results of the 1974 American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy survey. JAMA. 1976;235:928-30.

18. Fleischer DE, al-Kawas F, Benjamin S, et al. Prospective evaluation of complications in an endoscopy unit: Use of the A/S/G/E quality care guidelines. Gastrointest Endosc. 1992;38:411-14.

19. Arrowsmith JB, Gerstman BB, Fleischer DF, et al. Results from the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy/U.S. Food and Drug Administration collaborative study on complication rates and drug use in gastrointestinal endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 1991;37:421-7.

20. Vargo JJ, Holub JL, Faigel DO, et al. Risk factors for cardiopulmonary events during propofol-mediated upper endoscopy and colonoscopy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;24:955-63.

21. Freeman ML, Hennessy JT, Cass OW, et al. Carbon dioxide retention and oxygen desaturation during gastrointestinal endoscopy. Gastroenterology. 1993;105:331-9.

22. Vargo JJ, Zuccaro GJr, Dumot JA, et al. Automated graphic assessment of respiratory activity is superior to pulse oximetry and visual assessment for the detection of early respiratory depression during therapeutic upper endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;55:826-31.

23. Herman LL, Kurtz RC, McKee KJ, et al. Risk factors associated with vasovagal reactions during colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 1993;39:388-91.

24. Eckardt VF, Kanzler G, Schmitt T, et al. Complications and adverse effects of colonoscopy with selective sedation. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;49:560-5.

25. Seinelä L, Reinikainen P, Ahvenainen J. Effect of upper gastrointestinal endoscopy on cardiopulmonary changes in very old patients. Arch Gerontal Geriatr. 2003;37:25-32.

26. American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. Monitoring equipment for endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 1995;42:615-17.

27. Willey J, Vargo JJ, Connor JT, et al. Quantitative assessment of psychomotor recovery after sedation and analgesics for outpatient EGD. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:810-16.

28. Nelson DB. Infectious disease complications of GI endoscopy: Part II, exogenous infections. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;57:695-711.

29. Nelson DB, Jarvis WR, Rutala WA, et al. Multi-society guidelines for reprocessing flexible gastrointestinal endoscopes. Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2003;24:532-7.

30. American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. Guideline on infection control during GI endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;67:781-90.

31. American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. Transmission of infection by gastrointestinal endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 1993;39:885-8.

32. Ciancio A, Manzini P, Castagno F, et al. Digestive endoscopy is not a major risk factor for transmitting hepatitis C virus. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142:903-9.

33. Mikhail NN, Lewis DL, Omar N, et al. Prospective study of cross-infection from upper-GI endoscopy in a hepatitis C-prevalent population. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;65:584-8.

34. American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. Technology status evaluation report: Electrosurgical generators. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58:656-60.

35. Ladas SD, Karamanolis G, Ben-Soussan E. Colonic gas explosion during therapeutic colonoscopy with electrocautery. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:5295-8.

36. Ko CW, Riffle S, Shapiro JA, et al. Incidence of minor complications and time lost from normal activities after screening or surveillance colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;65:648-56.

37. Watabe N, Yamaji Y, Okamoto M, et al. Risk assessment for delayed hemorrhagic complications of colonic polypectomy: polyp-related factors and patient-related factors. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;64:73-8.

38. Gerstenberger PD, Plumeri PA. Malpractice claims in gastrointestinal endoscopy: Analysis of an insurance industry data base. Gastrointest Endosc. 1993;39:132-8.

39. Boitano LJ, Jordan T, Benditt JO. Noninvasive ventilation allows gastrostomy tube placement in patients with advanced ALS. Neurology. 2001;56:413-14.

40. Koch DG, Arguedas MR, Fallon MB. Risk of aspiration pneumonia in suspected variceal hemorrhage: the value of prophylactic endotracheal intubation prior to endoscopy. Dig Dis Sci. 2007;52:2225-8.

41. Evans LT, Saberi S, Kim HM, et al. Pharyngeal anesthesia during sedated EGDs: Is “the spray” beneficial? A meta-analysis and systematic review. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63:761-6.

42. Moore TJ, Walsh CS, Cohen MR. Reported adverse event cases of methemoglobinemia associated with benzocaine products. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:1192-6.

43. Ash-Bernal R, Wise R, Wright SM. Acquired methemoglobinemia. A retrospective series of 138 cases at 2 teaching hospitals. Medicine. 2004;83:265-73.

44. American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. Complications of upper GI endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;55:784-93.

45. Penston JG, Boyd EJ, Wormsley KG. Mallory-Weiss tears occurring during endoscopy: A report of seven cases. Endoscopy. 1992;24:262-5.

46. Yen HH, Soon MS, Chen YY. Esophageal intramural hematoma: an unusual complication of endoscopic biopsy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;62:161-3.

47. Wolfsen HC, Hemminger LL, Achem SR, et al. Complications of endoscopy of the upper gastrointestinal tract: a single-center experience. Mayo Clin Proc. 2004;79:1264-7.

48. Gelbmann CM, Ratiu NL, Rath HC, et al. Use of self-expandable plastic stents for the treatment of esophageal perforations and symptomatic anastomotic leaks. Endoscopy. 2004;36:695-9.

49. Hernandez LJ, Jacobson JW, Harris MS. Comparison among the perforation rates of Maloney, balloon and Savary dilation of esophageal strictures. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;51:460-2.

50. Green BT, Tendler DA. Cerebral air embolism during upper endoscopy: Case report and review. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61:620-3.

51. Chung SS, Lau JY, Sung JJ, et al. Randomised comparison between adrenaline injection alone plus heat probe treatment for actively bleeding ulcers. BMJ. 1997;314:1307-11.

52. Lau JY, Sung JJ, Lam YH, et al. Endoscopic retreatment compared with surgery in patients with recurrent bleeding after initial endoscopic control of bleeding ulcers. N Engl J Med. 1999;34:751-6.

53. Steigmann GV, Goff JS, Michaletz-Onody PA, et al. Endoscopic sclerotherapy as compared with endoscopic ligation for bleeding esophageal varices. N Engl J Med. 1992;326:1527-32.

54. Schuman BM, Beckman JW, Tedesco FJ. Complications of endoscopic injection sclerotherapy: A review. Am J Gastroenterol. 1987;82:823-30.

55. Laine L, El-Newihi HM, Migikovsky B, et al. Endoscopic ligation compared with sclerotherapy for the treatment of bleeding esophageal varices. Ann Intern Med. 1993;119:1-7.

56. Mitchell SL, Kiely DK, Lipsitz LA. The risk factors and impact on survival of feeding tube placement in nursing home residents with severe cognitive impairment. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157:327-32.

57. McClave SA, Chang W-K. Complications of enteral access. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58:739-51.

58. Gossner L, Keymling J, Hahn EG, et al. Antibiotic prophylaxis in percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG): A prospective randomized clinical trial. Endoscopy. 1999;31:119-24.

59. Jain NK, Larson DE, Schroeder KW. Antibiotic prophylaxis for percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy: A prospective, randomized, double-blind clinical trial. Ann Intern Med. 1987;107:824-8.

60. Larson DE, Burton DD, Schroeder KW, et al. Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy. Indications, success, complications, and mortality in 314 consecutive patients. Gastroenterology. 1987;93:48-52.

61. Lee TH, Lin JT. Clinical manifestations and management of buried bumper syndrome in patients with percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;68:580-4.

62. Cruz I, Mamel JJ, Brady PG, Cass-Garcia M. Incidence of abdominal wall metastasis complicating PEG tube placement in untreated head and neck cancer. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;62:708-11.

63. Cappell MS. Risk factors and risk reduction of malignant seeding of the percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy track from pharyngoesophageal malignancy: a review of all 44 known reported cases. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:1307-11.

64. McClave SA, DeMeo MT, DeLegge MH, et al. North American summit on aspiration in the critically ill patient: Consensus statement. J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2002;26:S80-5.

65. Maple JT, Petersen BT, Baron TH, et al. Direct percutaneous endoscopic jejunostomy: Outcomes in 307 consecutive attempts. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:2681-8.

66. Soetikno RM, Carr-Locke DL. Expandable metal tents for gastric-outlet, duodenal, and small intestinal obstruction. Gastrointest Endosc Clin North Am. 1999;9:447-58.

67. Berggreen PJ, Harrison ME, Sanowski RA, et al. Techniques and complications of esophageal foreign body extraction in children and adults. Gastrointest Endosc. 1993;39:626-30.

68. American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. Guideline for the management of ingested foreign bodies. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;55:802-6.

69. Mensink PBF, Haringsma J, Kucharzik T, et al. Complications of double balloon enteroscopy: A multicenter survey. Endoscopy. 2007;39:613-15.

70. Groenen MJM, Moreels TGG, Orient H, et al. Acute pancreatitis after double-balloon enteroscopy: An old pathogenetic theory revisited as a result of using a new endoscopic tool. Endoscopy. 2006;38:82-5.

71. Li F, Gurudu SR, DePetris G, et al. Retention of the capsule endoscope: A single-center experience of 1000 capsule endoscopy procedures. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;68:174-80.

72. Delvaus M, Ben Soussan E, Laurent V, et al. Clinical evaluation of the use of the M2A patency capsule system before a capsule endoscopy procedure, in patients with known or suspected intestinal stenosis. Endoscopy. 2005;37:801-7.

73. Nathan SR, Biernat L. Aspiration—An important complication of small-bowel video capsule endoscopy. Endoscopy. 2007;39:E343.

74. American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. Complications of colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;57:441-5.

75. Nelson DB, McQuaid KR, Bond JH, et al. Procedural success and complications of large scale screening colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;55:307-14.

76. Korman LY, Overholt BF, Box T, et al. Perforation during colonoscopy in endoscopic ambulatory surgical centers. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58:554-7.

77. Levin TR, Zhao W, Conell C, et al. Complications of colonoscopy in an integrated health care delivery system. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145:880-6.

78. Rathgaber SW, Wick TM. Colonoscopy completion and complication rates in a community gastroenterology practice. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;64:556-62.

79. Gatto NM, Frucht H, Sundararajan V, et al. Risk of perforation after colonoscopy and sigmoidoscopy: A population-based study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95:230-6.

80. Rosen L, Bub D, Reed J, et al. Hemorrhage following colonoscopic polypectomy. Dis Colon Rectum. 1993;36:1126-31.

81. Koobatian GJ, Choi PM. Safety of surveillance colonoscopy in long-standing ulcerative colitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1994;89:1472-5.

82. Lüning TH, Keemers-Gels ME, Barrendregt WB, et al. Colonoscopic perforations: a review of 30,366 patients. Surg Endosc. 2007;21:994-7.

83. Jensen DM, Machicado GA, Jutabha R, et al. Urgent colonoscopy for the diagnosis and treatment of severe diverticular hemorrhage. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:78-82.

84. Geller A, Petersen BT, Gostout CJ. Endoscopic decompression for acute colonic pseudo-obstruction. Gastrointest Endosc. 1996;44:144-50.

85. Suzuki N, Saunders BP, Thomas-Gibson S, et al. Colorectal stenting for malignant and benign disease: Outcomes in colo-rectal stenting. Dis Colon Rectum. 2004;47:1201-7.

86. Singh VV, Draganov P, Valentine J. Efficacy and safety of endoscopic balloon dilation of symptomatic upper and lower gastrointestinal Crohn’s disease strictures. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2005;39:284-90.

87. Iqbal CW, Chun YC, Farley DR. Colonoscopic perforations: A retrospective review. J Gastrointest Surg. 2005;9:1229-36.

88. Cobb WS, Heniford T, Sigmon LB, et al. Colonoscopic perforations: Incidence, management, and outcomes. Am Surg. 2004;70:750-8.

89. Nivatvongs S. Complications in colonoscopic polypectomy: An experience with 1555 polypectomies. Dis Colon Rectum. 1986;28:825-30.

90. Waye JD, Kahn O, Auerbach ME. Complications of colonoscopy and flexible sigmoidoscopy. Gastrointest Clin North Am. 1996;6:343-77.

91. Sica DA, Carl D, Zfass AM. Acute phosphate nephropathy—An emerging issue. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:1844-7.

92. Markowitz GS, Nasr SH, Klein P, et al. Renal failure due to acute nephrocalcinosis following oral sodium phosphate bowel cleansing. Hum Pathol. 2004;36:675-84.

93. Gumurdulu Y, Serin E, Ozer B, et al. Age as a predictor of hyperphosphatemia after oral phosphosoda administration for colon preparation. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;19:68-72.

94. Khurana A, McLean L, Atkinson S, Foulks CJ. The effect of oral sodium phosphate drug products on renal function in adults undergoing bowel endoscopy. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:565-7.

95. Heymann TD, Chopra K, Nunn E, et al. Bowel preparation at home: Prospective study of adverse events in elderly people. BMJ. 1996;313:727-8.

96. Marschall HU, Bartels F. Life-threatening complications of nasogastric administration of polyethylene glycol preparations (GoLYTELY) for bowel cleansing. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998;47:408-10.

97. Saad A, Rex DK. Colonoscopy-induced splenic injury: report of 3 cases and literature review. Dig Dis Sci. 2008;53:892-8.

98. Caprilli R, Viscido A, Frieri G, et al. Acute colitis following colonoscopy. Endoscopy. 1998;30:428-31.

99. American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. Complications of ERCP. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;57:633-8.

100. Freeman ML, Nelson DB, Sherman S, et al. Complications of endoscopic biliary sphincterotomy. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:909-18.

101. Freeman ML, DiSario JA, Nelson DB, et al. Risk factors for post-ERCP pancreatitis: A prospective, multicenter study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;54:425-34.

102. Masci E, Toti G, Mariani A, et al. Complications of diagnostic and therapeutic ERCP: A prospective multicenter study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:417-23.

103. Christensen M, Matzen P, Schulze S, Rosenberg J. Complications of ERCP: A prospective study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;60:721-31.

104. Cheon YK, Cho KB, Watkins JL, et al. Frequency and severity of post-ERCP pancreatitis correlated with extent of pancreatic ductal opacification. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;65:385-93.

105. Freeman ML, Guda NM. Prevention of post-ERCP pancreatitis: A comprehensive review. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;59:845-64.

106. Tarnasky PR, Palesch YK, Cunningham JT, et al. Pancreatic stenting prevents pancreatitis after biliary sphincterotomy in patients with sphincter of Oddi dysfunction. Gastroenterology. 1998;115:1518-24.

107. Saad AM, Fogel EL, McHenry L, et al. Pancreatic duct stent placement prevents post-ERCP pancreatitis in patients with suspected sphincter of Oddi dysfunction but normal manometry results. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;67:255-61.

108. Norton ID, Petersen BT, Bosco J, et al. A randomized trial of endoscopic biliary sphincterotomy using pure-cut versus combined cut and coagulation waveforms. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;3:1029-33.

109. Elta GH, Barnett JL, Wille RT, et al. Pure cut electrocautery current for sphincterotomy causes less post-procedure pancreatitis than blended current. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998;47:149-53.

110. Macintosh DG, Love J, Abraham NS. Endoscopic sphincterotomy by using pure-cut electrosurgical current and the risk of post-ERCP pancreatitis: A prospective randomized trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;60:551-6.

111. Wilcox CM, Canakis J, Monkemuller KE, et al. Patterns of bleeding after endoscopic sphincterotomy, the subsequent risk of bleeding, and the role of epinephrine injection. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:244-8.

112. Howard TJ, Tan T, Lehman GA, et al. Classification and management of perforations complicating endoscopic sphincterotomy. Surgery. 1999;126:658-63.

113. Enns R, Eloubeidi MA, Mergener K, et al. ERCP-related perforations: Risk factors and management. Endoscopy. 2002;34:293-8.

114. Loperfido S, Angelini G, Benedetti G, et al. Major early complications from diagnostic and therapeutic ERCP: A prospective multicenter study. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998;48:1-10.

115. Freeman ML, Overby C. Selective MRCP and CT-targeted drainage of malignant hilar biliary obstruction with self-expanding metallic stents. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58:41-9.

116. Harris A, Chan CH, Torres-Viera C, et al. Meta-analysis of antibiotic prophylaxis in endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Endoscopy. 1999;31:718-24.

117. Van den Hazel SJ, Speelman P, Dankert J, et al. Piperacillin to prevent cholangitis after endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. A randomized controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 1996;125:442-7.

118. Cotton PB, Connor P, Rawls E, Romagnuolo J. Infection after ERCP, and antibiotic prophylaxis: a sequential quality-improvement approach over 11 years. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;67:471-5.

119. Kozarek R, Hovde O, Attia F, et al. Do pancreatic duct stents cause or prevent pancreatic sepsis? Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58:505-9.

120. Baillie J. Pancreatic pseudocysts (Part I). Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;59:873-9.

121. Baillie J. Pancreatic pseudocysts (Part II). Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;60:105-13.

122. Mortensen MB, Fristrup C, Holm FS, et al. Prospective evaluation of patient tolerability, satisfaction with patient information, and complications after endoscopic ultrasonography. Endoscopy. 2005;37:146-53.

123. Buscarini E, De Angelis C, Arcidiacono PG, et al. Multicentre retrospective study on endoscopic ultrasound complications. Dig Liver Dis. 2006;38:762-7.

124. Das A, Sivak MVJr, Chak A. Cervical esophageal perforation during EUS: A national survey. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;53:599-602.

125. Mallery S, Van Dam J. Increased rate of complete EUS staging of patients with esophageal cancer using the nonoptical, wire-guided echoendoscope. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;50:53-7.

126. Gress FG, Hawes RH, Savides TJ, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration biopsy using linear array and radial scanning endosonography. Gastrointest Endosc. 1997;45:243-50.

127. Wiersema MJ, Vilmann P, Giovannini M, et al. Endosonography-guided fine-needle aspiration biopsy: Diagnostic accuracy and complication assessment. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:1087-95.

128. Brugge WR, Lewandrowski K, Lee-Lewandrowski E, et al. Diagnosis of pancreatic cystic neoplasms: A report of the cooperative pancreatic cyst study. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:1330-6.

129. Levy MJ, Norton ID, Clain JE, et al. Prospective study of bacteremia and complications of EUS FNA of rectal and perirectal lesions. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:684-9.

130. Eloubeidi MA, Gress FG, Savides TJ, et al. Acute pancreatitis after EUS-guided FNA of solid pancreatic masses: A pooled analysis from EUS centers in the United States. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;60:385-9.