CHAPTER 8 Complications of gastrointestinal endoscopy

Key Points

Introduction

1 Complications of upper gastrointestinal endoscopy

1.1 Infection complications

Endoscopy related infection may occur under the following circumstances:

Recently, the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE) published guidelines on infection control in gastrointestinal endoscopy (Box 1).

Box 1 ASGE guidelines on infection control during GI endoscopy

1.1.1 Endogenous complications

Bacteremia can occur after any endoscopic procedure due to bacterial translocation as a result of mucosal trauma that occurs during endoscopy. Bacteremia is thought of as a surrogate marker for infective endocarditis (IE) risk. However, there are currently no data to prove a causal link between endoscopic procedures and IE. In like manner, there are no data to demonstrate that antibiotic prophylaxis in the peri-endoscopic period decreases the risk of IE (see Ch. 2.2). Although previous recommendations have been to administer antibiotic prophylaxis prior to procedures with high risk of bacteremia, namely esophageal dilation and sclerotherapy, the most recent ASGE guidelines stated that this policy to prevent IE is no longer recommended before endoscopic procedures. Notable exceptions to this guideline are detailed in Box 2.

1.2 Perforation

1.2.1 Endoscopic management of perforations

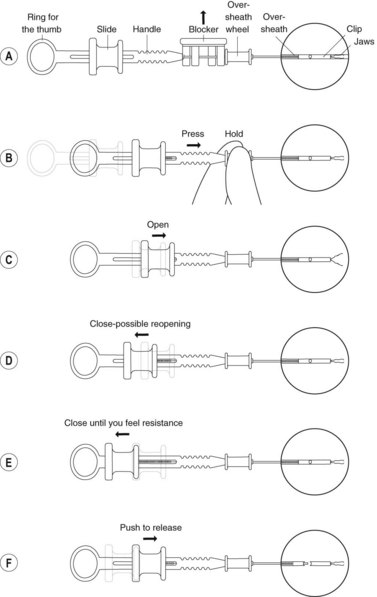

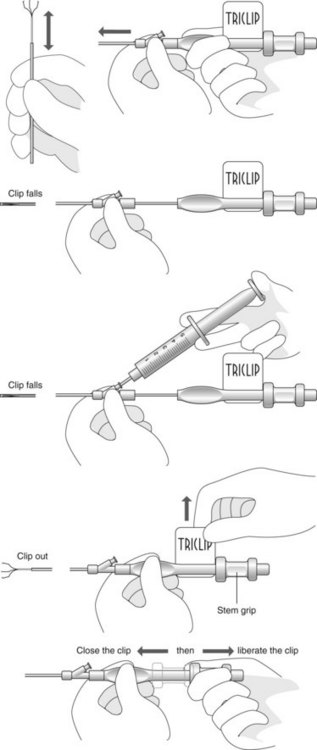

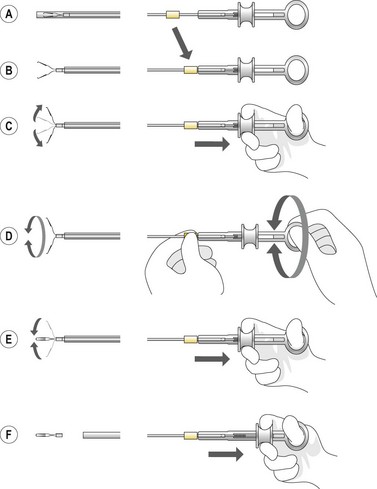

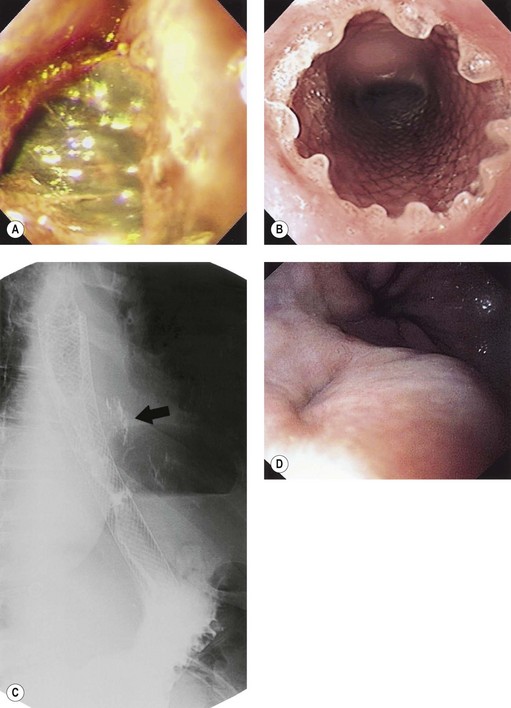

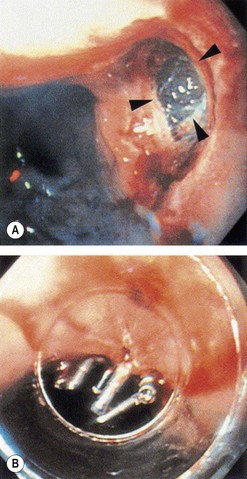

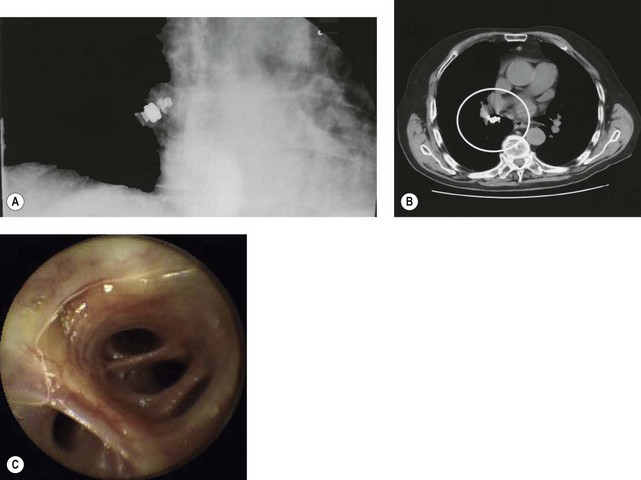

Box 4 Technique of closure of perforations with clips (Figs 2–5)

![]() Clinical Tips

Clinical Tips

1.3 Bleeding

1.3.1 Management of antithrombotic agents in patients undergoing upper endoscopic procedures

2 Complications related to specific upper gastrointestinal procedures

2.1 Dilation and enteral stenting

Complications related to dilation of benign and malignant strictures of the gastrointestinal tract and of pneumatic dilation in achalasia patients are detailed in Chapter 7.1. Complications of enteral stenting are discussed in Chapter 7.3.

2.2 Hemostatic technique

2.2.1 Endoscopic non-variceal hemostasis

2.2.2 Endoscopic variceal hemostasis

2.3 Polypectomy and endoscopic mucosal resection

Box 7 ASGE recommendations for the management of gastric polyps

2.3.1 Endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR)

| Bleeding | Most common complication of EMR (up to 17% of cases). Most bleeding is immediate, but can be delayed (>24 h). Most important risk factor for delayed bleeding is immediate bleeding. Size >1–2 cm has been reported to be another risk factor for bleeding. No association has been found between risk of bleeding and EMR technique, lesion morphology (flat, raised, or depressed), type of electrocautery current used, amount of saline injected, and location of lesion except in duodenum. Bleeding is best managed with epinephrine injection and clip placement, because this method eliminates the risk of additional cautery injury to the EMR site. |

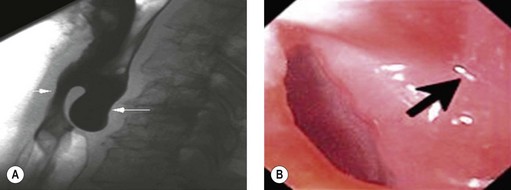

| Perforation | Gastric EMR perforation rate is high (1–5%). Avoid performing EMR in patients who had prior attempts at endoscopic resection. Scar tissue may prevent adequate lifting of the lesion and, thus, may increase risk of perforation. Small perforations that are recognized early in stable patients can be managed conservatively with clip placement (Fig. 7). Patients should be placed nil per os and treated with broad spectrum antibiotics. |

| Luminal stenosis | It has been described after extensive luminal resections, mainly when more than three-fourths of the luminal circumference has been excised in one endoscopic session. Luminal stenosis occurs most commonly after EMR of esophageal lesions. Incremental resections in multiple treatment sessions may decrease the risk of post-EMR strictures. Post-EMR strictures can be treated successfully with serial dilations and/or temporary stent placement. |

2.4 Ablative techniques

Complications associated with various ablative techniques are described in Table 2.

Table 2 Complications associated with different ablative techniques

| Laser light | Mortality 1% Perforation rate: 1–9% Major bleeding: up to 12% Others: Stricture and fistula formation |

| Photodynamic therapy (PDT) | Strictures: up to 30% Prolonged skin sensitivity Perforation and fistula formation Others: dysphagia, odynophagia, chest pain, fever, nausea (all occur commonly) |

| Argon plasma coagulation (APC) | Serious complications are very uncommon Abdominal distention is common Strictures are uncommon but can occur as a late complication |

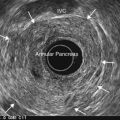

3 Complications of endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS)

3.1 Non-FNA related complications

3.2 FNA-related complications

3.2.1 Infectious complications

3.2.3 Hemorrhage

3.2.4 Celiac plexus blockade and neurolysis

4 Complications of device-assisted enteroscopy and capsule endoscopy

4.1 Device-assisted enteroscopy

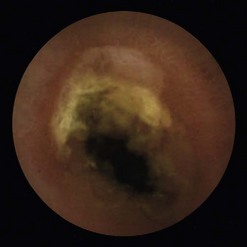

4.2 Capsule endoscopy

Anderson MA, Ben-Menachem T, Gan SI, et al. Management of antithrombotic agents for endoscopic procedures. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;70:1060-1070.

Banerjee S, Shen B, Baron TH, et al. Antibiotic prophylaxis for GI endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;67:791-798.

Banerjee S, Shen B, Nelson DB, et al. Infection control during GI endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;67:781-790.

Barkay O, Khashab M, Al-Haddad M, et al. Minimizing complications in pancreaticobiliary endoscopy. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2009;11:134-141.

Eisen GM, Baron TH, Dominitz JA, et al. Complications of upper GI endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;55:784-793.

Gerson LB, Tokar J, Chiorean M, et al. Complications associated with double balloon enteroscopy at nine US centers. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:1177-1182.

Guidelines on Complications of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. See ‘Guidelines Index’. 2006 www.bsg.org.uk Accessed January 5, 2010

Li F, Gurudu SR, De Petris G, et al. Retention of the capsule endoscope: a single-center experience of 1000 capsule endoscopy procedures. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;68(1):174-180.

Liao Z, Gao R, Xu C, et al. Indications and detection, completion, and retention rates of small-bowel capsule endoscopy: a systematic review. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71:280-286.

Raju GS. Endoscopic closure of gastrointestinal leaks. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:1315-1320.

Siersema PD, Homs MY, Haringsma J, et al. Use of large-diameter metallic stents to seal traumatic nonmalignant perforations of the esophagus. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58:356-361.

Tabib S, Fuller C, Daniels J, et al. Asymptomatic aspiration of a capsule endoscope. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;60:845-848.

Tsunada S, Ogata S, Ohyama T, et al. Endoscopic closure of perforations caused by EMR in the stomach by application of metallic clips. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;57(7):948-951.