Chapter 14 Complications of Facet Joint Injections and Medial Branch Blocks

Appropriate Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education mentored subspecialty training in interventional pain management is vital to ensure patient-centered care.

Appropriate Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education mentored subspecialty training in interventional pain management is vital to ensure patient-centered care. A thorough understanding of the spinal anatomy is vital to procedural success. Extrapolation of three-dimensional needle placement using two-dimensional ultrasound and fluoroscopic guidance is crucial for accurate needle placement.

A thorough understanding of the spinal anatomy is vital to procedural success. Extrapolation of three-dimensional needle placement using two-dimensional ultrasound and fluoroscopic guidance is crucial for accurate needle placement. Although uncommon, devastating complications from facetogenic intraarticular or median branch injections have been reported.

Although uncommon, devastating complications from facetogenic intraarticular or median branch injections have been reported.Introduction

Facetogenic sources of pain are common, accounting for approximately 40% of thoracic and cervical complaints and 30% of lumbar pain.1–7 These are disorders of older adults; 89.2% of people 60 to 69 years of age have facet joint arthropathy,8 but there is little correlation in the cervical and thoracic regions. Predicatively, facetogenic interventions are the second most commonly used and gratifying procedures performed by pain management physicians in the United States because they are relatively easy to perform with reliable radiographic landmarks, very good outcomes, and reported complications described to occur very rarely.

In a recent guideline statement, the American Society of Interventional Pain Physicians did not recommend intraarticular injections for either diagnostic or therapeutic benefit (level III evidence).9 The International Spine Intervention Society described thoracic intraarticular injections as emerging procedures and did not provide any comments on the cervical or lumbar level.10 The American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Chronic Pain Management and the American Society of Regional Anesthesia (ASRA) and Pain Medicine reported that randomized placebo controlled trials demonstrated equivocal evidence supporting intraarticular injections, and although observational studies provided evidence for short-term pain relief, they summarily described the evidence as “may be used for symptomatic relief of facet-mediated pain.”11 Both guidelines suggest better evidence (level I or II) with median branch injections for diagnostic and therapeutic benefit using 80% pain reduction with two comparative controlled diagnostic blocks, and based on Guyatt et al’s12 criteria, IB recommendations for radiofrequency (RF) neurotomy.9

Despite appropriate care, significant and devastating complications have been described as scattered case reports, including radicular artery injury and epidural abscesses (Box 14-1).

Selected Complications

Vascular Injury

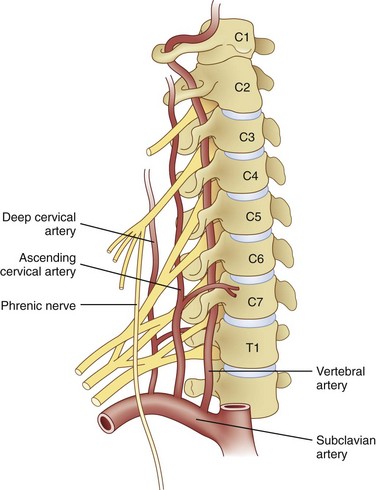

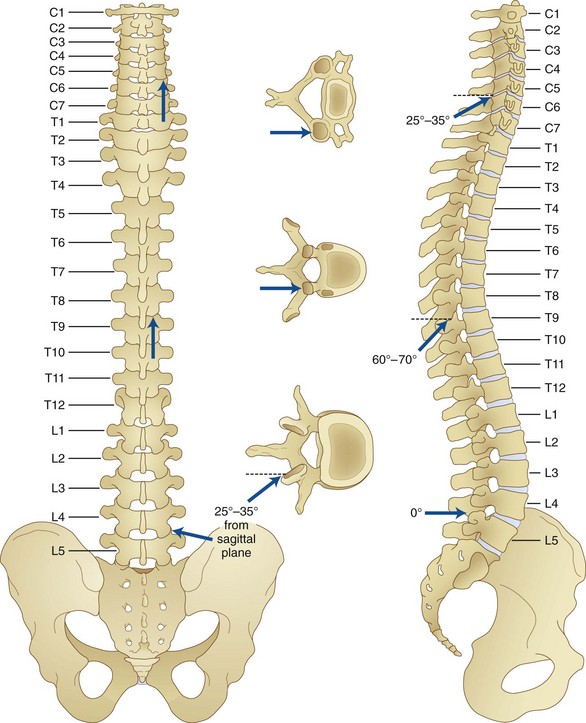

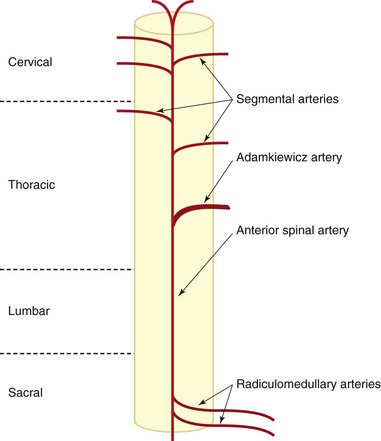

Huntoon13 investigated cervical blood flow in a cadaveric study and noted that the ascending and deep cervical arterial branches may contribute significantly to the anterior segmental arteries, and anterior spinal artery flow may be susceptible to injury during interventional procedures (Fig. 14-1). There have been unpublished reports of quadriplegia from vascular occlusion by particulate steroid after attempted cervical zygapophyseal interventions. Despite well-described lateral and prone approaches for cervical median branch blocks and rhizotomies, the prone technique hypothetically may be safer because there are more reliable osteal landmarks during needle placement; however, comparative studies are lacking.

Image guidance is required. Tetraplegia was reported in a case using only landmarks to guide needle placement14 and is not advocated. Image guidance, by either ultrasound or fluoroscopic means, is essential.

The most publicized and largest segmental spinal artery is the artery of Adamkiewicz. It is vitally important to reinforce the American Society of Anesthesiologists in the thoracolumbar region. It has a variable anatomic course. The Adamkiewicz artery is typically located between T8 and L3, but it is at T9 or T10 in 50% of people and comes from the left side in 75% of cases. Additional radiculomedullary arteries were found in 43% of patients.15,16

These important reinforcing segmental spinal arteries have variable location segmentally (Fig. 14-2) but consistent intraforaminal anatomy as they course in the superior anterior location of the foramen beneath the pedicle.17 Obviously, inadvertent needle placement can result in injury. Despite well-described lateral and prone approaches for cervical median branch blocks and rhizotomies, the prone technique hypothetically may be safer because there are more reliable osteal landmarks during needle placement; however, comparative studies are lacking.

Fig. 14-2 Diagram of spinal cord blood supply.

(Modified from Charles YP, Barbe B Beaujeux R, et al: Relevance of the anatomical location of the Adamkiewicz artery in the spine, Surg Radiol Anat 33(1):3-9, 2010.)

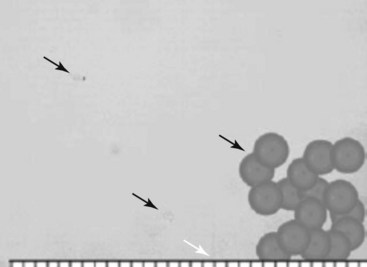

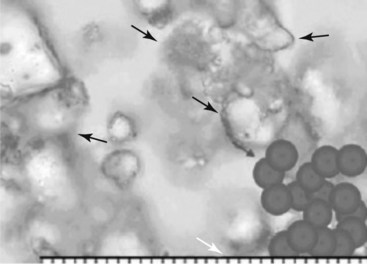

Huntoon13 investigated cervical blood flow in a cadaveric study and noted that the ascending and deep cervical arterial branches may contribute significantly to the anterior segmental arteries. Consequently, the anterior spinal artery flow may be susceptible to injury during interventional procedures. Steroids for spinal interventional procedures are not created equal because homogenicity and potency are variable. Derby et al18 investigated particle size and aggregation frequency of commonly used spinal corticosteroids (Table 14-1). The larger the particle size and the higher the aggregation, the more likely ischemic injury can result from embolic phenomena.

Table 14-1 Particle Size and Aggregation Potential for Commonly Used Corticosteroids for Spinal Injections

| Steroid | Particle Size | Aggregation |

|---|---|---|

| Dexamethasone | 5–10× smaller than RBCs (Fig. 14-3) | None |

| Triamcinolone | Varied in size, often >RBCs (Fig. 14-4) | High aggregation |

| Betamethasone | Varied in size, often >RBCs | High aggregation |

| Methylprednisolone | Uniform size, smaller than RBC | Few aggregations |

RBC, red blood cell.

Fig. 14-3 Dexamethasone compared to red blood cells.

(From Derby R, Lee SH, Date ES, et al: Size and aggregation of corticosteroids used for epidural injections, Pain Med 9(2):227-234, 2008.)

Fig. 14-4 Triamcinolone aggregates compared to red blood cells.

(From Derby R, Lee SH, Date ES, et al: Size and aggregation of corticosteroids used for epidural injections, Pain Med 9(2):227-234, 2008.)

Inadvertent vascular ischemic injury after steroid particulate injection or vascular injury during cervical transforaminal injections.19,20 has become increasingly common, and corollaries should be drawn to facetogenic interventions. There have been unpublished reports of quadriplegia from vascular occlusion by particulate steroid after attempted cervical zygapophyseal interventions.

Furthermore, studies for facet and epidural interventions comparing particulate versus nonparticulate steroids found no statistical difference in efficacy.21 Injection under live fluoroscopy with or without digital subtraction may help elucidate intravascular needle placement.

Local tenderness has been reported in many investigations. Dobrogowsi et al22 investigated strategies to reduce the inflammatory pain associated with the lesioning. In a randomized prospective trial, patients were randomized to intraoperative methylprednisolone (10 mg), pentoxifylline (10 mg), or saline (1 mL). No “severe local tenderness” was reported in either the methylprednisolone group or the pentoxifylline group, with minor tenderness resolving within 1 month, as compared with the saline group, which had four of 15 patients with severe pain at 1 week and one patient for longer than 1 month. Other authors report a 3-day dosage of diclofenac to be effective in reducing procedural pain after conventional RF neurotomy of lumbar median branches.23

Infection

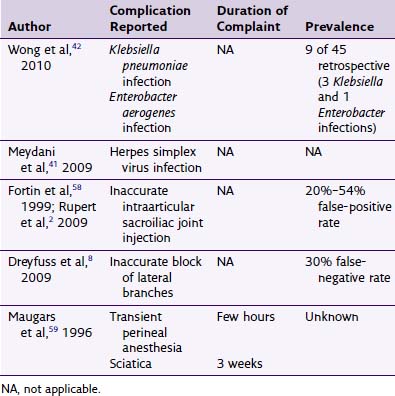

Although there have been several case reports of infectious complications, appreciating the scope of facetogenic interventions, these complications continue to be very rare. Some authors contend that the immunosuppressive effects of steroids contribute to the infectious complication potential (Table 14-2). A consistent theme in successful treatment is prompt diagnosis and a high index of suspicion.

Table 14-2 Reported Infectious Complications After Zygapophyseal Interventions

| Author, Year | Complication Reported |

|---|---|

| Heenan et al,35 1995 | Septic arthritis |

| Cook et al,39 1999 | Paraspinal abscess |

| Magee et al,57 2000 | Paraspinal abscess |

| Rombauts et al,58 2000 | Septic arthritis |

| Alcock et al,24 2003 | Epidural abscess |

| Doita et al,34 2003 | Septic arthritis |

| Orpen et al,59 2003 | Septic arthritis |

| Gaul et al,38 2005 | Iatrogenic paraspinal abscess and meningitis |

| Weingarten et al,60 2006 | Septic arthritis |

| Falagas et al,43 2006 | Spondylodiscitis |

| Park et al,40 2007 | Paraspinal communicated with epidural abscess |

| Hoelzer et al,41 2008 | Endocarditis after paraspinal abscess |

Epidural Abscess

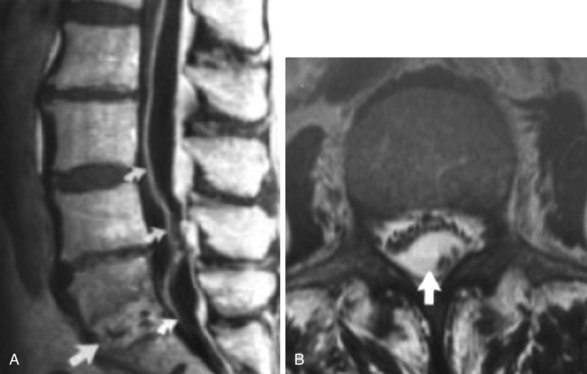

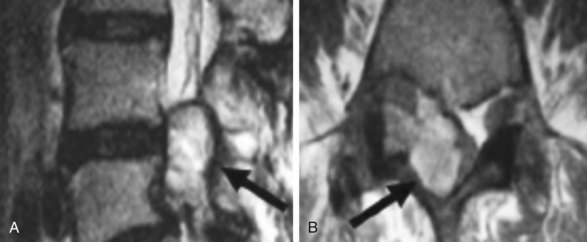

Epidural abscess (Fig. 14-5, A) can occur spontaneously, with a reported incidence of 0.2 to 1.2 per 10,000 hospital admissions.24 Early diagnosis is important for reduced morbidity.25 It is very infrequently associated with facetogenic interventions (only one reported case). Commonly, nonspecific inflammatory markers, including C-reactive protein and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), are elevated. Patients may also develop leukocytosis, fever, and commonly complain of back pain. Progressive clinical phases have been described for epidural infection leading to epidural abscess, described by van Zundert.26 Phase I involves backache and local tenderness; phase II is associated with radicular pain, fever, neck stiffness, and rigidity and commonly occurs 2 to 3 days later; phase III presents with sensory, motor, or reflex depression (often 3 to 4 days later); and phase IV is associated with paralysis.26

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with gadolinium contrast is a very sensitive diagnostic tool, in that 80% to 90% of cases were correctly diagnosed.24 When neurologic deterioration occurs, decompression via laminectomy is warranted and should be used within 36 hours, although neurologic sequela can still be significant.27

Staphylococci are the most common species identified (57% to 73% in epidural abscesses), although other gram-positive, negative, anaerobic mycobacteria and fungi have been implicated.28,29 The most common source of infection is a hematogenous source, typically from furunculosis.30 Spread from adjacent paraspinal structures has also been implicated, and in a review by Darouiche et al,31 44% of 43 patients had vertebral body osteomyelitis (Fig. 14-5, B). Intravenous (IV) bacteriocidal antibiotics should be started as early as possible and continued for 4 weeks, and enteral or parenteral therapy continued for 8 to 12 weeks is typically advocated.31 Therapy should be modified according to speciation and antibiotic resistance profile if isolation is achievable.

Septic Facet Joint Arthritis

Septic arthritis has been described secondary to zygapophyseal joint injections, both in the cervical and lumbar arena, although similar to epidural abscesses, it is more common via hematogenous spread.32,33 The causative organisms are most commonly staphylococci. Again, a high level of suspicion is required to make a prompt diagnosis because early treatment with IV antibiotics is necessary. The presentation is similar to that of epidural abscess, and it is often difficult to differentiate it from spondylodiscitis, although typically septic arthritis is more painful.28,34

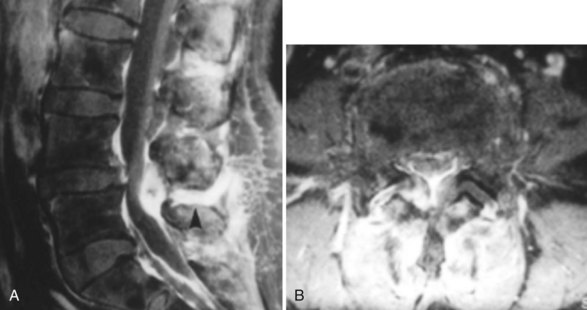

Lumbar facet septic arthritis typically occurs unilaterally and rarely occurs bilaterally, although it has been reported.34 Radiographic evidence includes widening of the facet joint on plain radiographs, ultra-high signal intensity on T2-weighted images, and ring enhancement on gadolinium enhanced T1-weighted images (Fig. 14-6).28,35,36

Similar to epidural abscess treatment, IV antibiotics are given for 4 to 6 weeks to follow objective functional endpoints for treatment, such as reduction in ESR or normalization of leukocytosis. In cases without epidural extension, percutaneous drainage was successful in treatment approximately 85% of the time.37 Surgical decompression is required if antibiotics fail or neurologic deterioration occurs. Muffoletto et al37 suggest that patients with septic facet arthritis from iatrogenic causes were more likely to require surgical intervention than those with hematogenous causes.

Paraspinal Abscess

Gaul et al estimated the risk of central nervous system infectious complications after paraspinal pain intervention to be approximately one in 1000.38 There have been numerous case reports with significant morbidity, including endocarditis.39–41

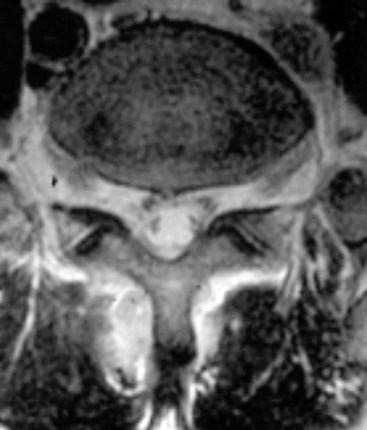

Paraspinal abscess presentation, onset, and treatment are similar to the aforementioned infectious complications (Fig. 14-7).42 As with other therapies, prompt diagnosis and institution of bactericidal therapy are paramount.

Spondylodiscitis

Spondylodiscitis incidence from iatrogenic facetogenic interventional sources is rare,43 and the incidence from all causes is 2.4 in 100,000.44 The typical presentation is vague dull back pain that increases in character with continued progression of clinical signs, including fever, leukocytosis, and ESR. The aforementioned radiographic investigations, including MRI, and serologic and tissue assessment, including blood cultures biopsy, are suggested (Fig. 14-8).

Epidural Hematoma

Although the incidence of epidural hematoma formation associated with spinal procedures approximates one in 150,000 epidural procedures and one in 222,000 for spinal anesthetics, the incidence after facet interventions is largely unknown.45 The AASRA developed guidelines to avoid the risk of bleeding complicating neuraxial procedures, and although largely for epidural and spinal perioperative anesthesia or analgesia, they can be used in the chronic pain realm. Obviously, if anatomic vascular variation is present, a predisposition to bleeding complications may be increased. The epidural space is an area surrounded by a plexus of epidural veins, commonly implicated in hematoma formation.

Nam et al46 reported two cases of epidural hematoma after facet block (Fig. 14-9 and Table 14-3). Both patients presented with back pain and radicular pain, but no systemic disorders or coagulopathies were identified. Subsequently, both resolved with appropriate treatment, one requiring a multilevel laminectomy.

| Author, Year | Complication Reported |

|---|---|

| Goldstone et al,49 1987 | Spinal anesthesia |

| Cohen,50 1994 | Postdural puncture headache |

| Heckmann et al,14 2006 | Transient tetraplegia |

| Nam et al,46 2010 | Epidural hematoma |

| Kay et al,51 1994 | Pituitary–adrenal axis suppression* |

* Extrapolated from epidural steroid injections.

Treatment should not be delayed until radiographic confirmation. MRI with low signal intensity on T1 and high signal intensity on T2 is suggestive of an acute bleed. Slightly high signal on T1 and T2 is suggestive of an subacute bleed. Early neurosurgical consultation is paramount because the absence of neurologic sequelae is contingent on hematoma evacuation within 8 hours of neurologic deficit.47

Spinal Anesthesia and Post-Dural Puncture Headache

The anatomy of the spinal elements predisposes to potential dural puncture. As described in the chapter on intraarticular injection (see Chapter 12), the architecture and orientation of the facet joint vary with function and position within the vertebral column. The cervical facet joints are between the articular pillars of the vertebrae and are oriented approximately 45 degrees from the transverse plain and 80 degrees from the sagittal. The cervical facet joint can accommodate approximately 0.5 to 1.0 mL of fluid. The thoracic facet joint can accommodate no more than 0.75 mL of fluid and is more vertically oriented than the lumbar or cervical facet joints. On average, they are approximately 75 degrees from the sagittal and transverse planes. The lumbar facet joint is oriented approximately 78.5 degrees from the transverse and 122 degrees from the sagittal planes, accommodating an average of 1.0 to 1.5 mL of fluid (Fig. 14-10).48

The dural sleeve of the exiting nerve root extends laterally and is caudal to the ipsilateral pedicle. Spinal anesthesia after lumbar facet intraarticular injection has been described.49 The authors postulated inadvertent needle placement and trajectory, potential dural cuff penetration, or intraneural injection as potential explanations.

After dural puncture, postdural puncture headache can occur, and after isolated penetration, it is largely contingent on needle gauge and bevel shape. Typical needle gauges (22 or 25 gauge) for intraarticular or median branch procedures lessen the chance of dural puncture. Given this, Cohen50 described this complication after successful lumbar facet block.

Pituitary–Adrenal Axis Suppression

Although numerous studies have demonstrated pituitary–adrenal suppression with epidural or intraarticular administration of glucocorticoids,51–53 none has investigated axis depression from zygapophyseal interventions. From the available data, hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis suppression could be assumed to be depressed for 4 weeks, and insulin sensitivity may be adversely affected for approximately 1 week. Cushing syndrome, steroid myopathy, aseptic meningitis, and anaphylactoid reactions have been reported after single epidural steroid injections.54,55 Other glucocorticoid side effects, including musculoskeletal, ophthalmologic, gastrointestinal, cardiovascular, secondary cortisol deficiency, gynecologic, neurologic, hematologic, gynecologic, psychiatric, and dermatologic, have been described.56

1 Datta S, Lee M, Falco FJ, et al. Systematic assessment of diagnostic accuracy and therapeutic utility of lumbar facet joint interventions. Pain Physician. 2009;12:437-460.

2 Alturi S, Datta S, Falco FJE, Lee M. Systematic review of diagnostic utility and therapeutic effectiveness of thoracic facet joint interventions. Pain Physician. 2008;11:611-629.

3 Schwarzer AC, Wang S, Bogduk N, et al. Prevalence and clinical features of lumbar zygapophysial joint pain: a study in an Australian population with chronic low back pain. Ann Rheum Dis. 1995;54:100-106.

4 Manchikanti L, Manchikanti KN, Pampati V, et al. The prevalence of facet-joint-related chronic neck pain in postsurgical and nonpostsurgical patients: a comparative evaluation. Pain Practice. 2008;8:5-10.

5 Lord SM, Barnsley L, Wallis BJ, Bogduk N. Chronic zygapophysial joint pain after whiplash: A placebo-controlled prevalence study. Spine. 1996;21:1737-1744.

6 Manchukonda R, Manchikanti KN, Cash KA, et al. Facet joint pain in chronic spinal pain: an evaluation of prevalence and false-positive rate of diagnostic blocks. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2007;20:539-545.

7 Kalichman L, Li L, Kim DH, et al. Facet joint osteoarthritis and low back pain in the community-based population. Spine. 2008;33:2560-2565.

8 Kalichman L, Li L, Kim DH, et al. Facet joint osteoarthritis and low back pain in the community- based population. Spine. 2008;33:2560-2565.

9 Manchikanti L, Boswell MV, Singh V, et al. Comprehensive evidence-based guidelines for interventional techniques in the management of chronic spinal pain. Pain Physician. 2009;12:699-802.

10 Bogduk N, International Spine Intervention Society Practice guidelines spinal diagnostics and treatment procedures. (San Francisco) 2004.

11 Practice guidelines for chronic pain management: An updated report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Chronic Pain Management and the American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine. Anesthesiology. 2010;112:810-833.

12 Guyatt G, Gutterman D, Baumann MH, et al. Grading strength of recommendations and quality of evidence in clinical guidelines: report from an American College of Chest Physicians task force. Chest. 2006;129:174-181.

13 Huntoon MA. Anatomy of the cervical intervertebral foramina: vulnerable arteries and ischemic neurologic injuries after transforaminal epidural injections. Pain. 2005;117(1-2):104-111.

14 Heckmann JG, Maihofner C, Lanz S, et al. Transient tetraplegia after cervical facet joint injection for chronic neck pain administered without imaging guidance. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2006;108:709-711.

15 Lazorthes G, Gouaze A, Zadeh JO, et al. Arterial vascularization of the spinal cord. J Neurosurg. 1971;35:253-262.

16 Charles YP, Barbe B Beaujeux R, et al. Relevance of the anatomical location of the Adamkiewicz artery in the spine. Surg Radiol Anat. 2010;33(1):3-9.

17 Glaser SE, Shah RV. Root cause analysis of paraplegia following trans-foraminal epidural steroid injections: the “unsafe triangle.”. Pain Physician. 2010;13:237-244.

18 Derby R, Lee SH, Date ES, et al. Size and aggregation of corticosteroids used for epidural injections. Pain Med. 2008;9(2):227-234.

19 Rathmell JP, Aprill C, Bogduk N. Cervical transforaminal injection of steroids. Anesthesiology. 2004;100:1595-1600.

20 Rozin L, Rozin R, Koehler SA, et al. Death during transforaminal epidural steroid nerve root block (C7) due to perforation of the left vertebral artery. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 2003;24:351-355.

21 Lee JW, Park KW, Chung SK, et al. Cervical transforaminal epidural steroid injection for the management of cervical radiculopathy: a comparative study of particulate versus non-particulate steroids. Skeletal Radiol. 2009;38(11):1077-1082.

22 Dobrogowski J, Wrzosek A, Wordliczek J. Radiofrequency denervation with or without addition of pentoxifylline or methylprednisolone for chronic lumbar zygapophysial joint pain. Pharmacol Rep. 2005;57:475-480.

23 Ma K, Yiqun M, Wang W, et al. Efficacy of diclofenac sodium in pain relief after conventional radiofrequency denervation for chronic facet joint pain: a double blind randomized controlled trial. Pain Med. 2010;12(1):27-35.

24 Alcock E, Regaard A, Browne J. Facet joint injection: a rare form cause of epidural abscess formation. Pain. 2003;103:209-210.

25 Mackenzie AR, Laing RBS, Kaar GF, Smith FW. Spinal epidural abscess: the importance of early diagnosis and treatment. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1998;65:209-212.

26 Van Zundert A. The epidural abscess: diagnosis and treatment. In: Highlights in regional anaesthesia and pain therapy IX. Rome: Italy Cyprint Ltd; 2000:159-162.

27 Danner RL, Hartman BJ. Update of spinal epidural abscess: 35 cases and review of literature. Rev Infect Dis. 1987;9:265-274.

28 Ergan M, Macro M, Benhamou CL, et al. Septic arthritis of lumbar facet joints: a review of six cases. Rev Rheum Engl Ed. 1997;64:386-395.

29 Bruma OJ, Craane H, Kunst MW. Vertebral osteomyelitis and epidural abscess due to mucormycosis, a case report. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 1979;81(1):39-44.

30 Gouche CR, Graziotti P. Extradural abscess following local anaesthetic and steroid injection for chronic low back pain. Br J Anaesth. 1990;65:427-429.

31 Darouiche RO, Hamil RJ, Greenberg, et al. Bacterial spinal epidural abscess: review of 43 cases and literature survey. Medicine. 1992;71:369-385.

32 Stecher JM, El-Khoury GY, Hitchon PW. Cervical facet joint arthritis: a case report. Iowa Orthop J. 2010;30:182-187.

33 Ogura T, Mikami Y, Hase H, et al. Septic arthritis of a lumbar facet joint associated with epidural and paraspinal abscess. Orthopedics. 2005;28(2):173-175.

34 Doita M, Nishida K, Miyamoto H, et al. Septic arthritis of bilateral lumbar facet joints: report of a case with MRI findings in the early stage. Spine. 2003;28:198-202.

35 Heenan SP, Britton J. Septic arthritis in a lumbar facet joint: a rare cause of epidural abscess. Neuroradiology. 1995;37:109-112.

36 Fujiwara A, Tamai K, Yamato M, et al. Septic arthritis of a lumbar facet joint: report of a case with early MRI findings. J Spinal Disord. 1998;11:452-453.

37 Muffoletto AJ, Ketonen LM, Mader JT, et al. Hematogenous pyogenic facet joint infection. Spine. 2001;26:1570-1576.

38 Gaul C, Neundorfer B, Winterholler M. Iatrogenic (para-) spinal abscesses and meningitis following injection therapy for low back pain. Pain. 2005;116:407-410.

39 Cook NJ, Hanrahan P, Song S. Paraspinal abscess following facet joint injection. Clin Rheumatol. 1999;18:52-53.

40 Park MS, Moon SH, Hahn SB, Lee HM. Paraspinal abscess communicated with epidural abscess after extra-articular facet joint injection. Yonsei Med J. 2007;48:711-714.

41 Hoelzer BC, Weingarten TN, Hooten WM, et al. Paraspinal abscess complicated by endocarditis following a facet joint injection. Eur J Pain. 2008;12:261-265.

42 Puehler W, Brack A, Kopf A. Extensive abscess formation after repeated paravertebral injections for the treatment of chronic back pain. Pain. 2005;113:427-429.

43 Falagas ME, Bliziotis IA, Mavrogenis AF, Papagelopoulos PJ. Spondylodiscitis after facet joint injection: a case report and a review of literature. Scand J Infect Dis. 2006;38(4):295-299.

44 Titlic M, Josipovic-Jelic Z. Spondylodiscitis. Bratisl Lek Listy. 2008;109(8):345-347.

45 Horlocker TT, Rowlingson JC, Enneking FK, et al. Regional anesthesia in the patient receiving antithrombotic or thrombolytic therapy: American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine Evidence-Based Guidelines (Third Edition). Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2010;35(1):64-101.

46 Nam KH, Choi CH, Yang MS, Kang DW. Spinal epidural hematoma after pain control procedure. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2010;48:281-284.

47 Vandermeulen EP, Van Aken H, Vermylen J. Anticoagulants and spinal-epidural anesthesia. Anesth Analg. 1994;79:1165-1177.

48 Punjabi MM, Oxland T, Takata K, et al. Articular facets of the human spine. Quantitative three-dimensional anatomy. Spine. 1993;18:1298-1310.

49 Goldstone JC, Pennant JH. Spinal anaesthesia following facet joint injection. A report of two cases. Anaesthesia. 1987;42:754-756.

50 Cohen SP. Postdural puncture headache and treatment following successful lumbar facet block. Pain Digest. 1994;4:283-284.

51 Kay J, Findling JW, Raff H. Epidural triamcinolone suppresses the pituitary-adrenal axis in human subjects. Anesth Analg. 1994;79:501-505.

52 Ward A, Watson J, Wood P, et al. Glucocorticoid epidural for sciatica: Metabolic and endocrine sequelae. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2002;41:68-71.

53 Cook DM, Meikle AW, Bowman R. Systemic absorption of triamcinolone after a single intraarticular injections suppresses the pituitary-adrenal axis [abstract]. Clin Res. 1988;36:121A.

54 Knight CL, Burnell JC. Systemic side effects of extradural steroids. Anaesthesia. 1980;35:593-594.

55 Boonen S, Van Distel G, Westhovens R, et al. Steroid myopathy induced by epidural triamcinolone injection. Br J Rheumatol. 1995;34:385-386.

56 Nesbit LT. Minimizing complications from systemic glucocorticosteroid use. Dermatol Clin. 1995;13:925-939.

57 Magee M, Kannangara S, Dennien B. Paraspinal abscess complicating facet joint injection. Clin Nucl Med. 2000;25:71-77.

58 Rombauts PA, Linden PM, Buyse AJ, et al. Septic arthritis of a lumbar facet joint caused by Staphylococcus aureus. Spine. 2000;25:1736-1738.

59 Orpen NM, Birch NC. Delayed presentation of septic arthritis of a lumbar facet joint after diagnostic facet joint injection. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2003;16:285-287.

60 Weingarten TN, Hooten WM, Huntoon MA. Septic facet joint arthritis after a corticosteroid facet injection. Pain Med. 2006;7(1):52-56.