Chapter 13 Complications of Epidural Injections

Epidural injections for the treatment of chronic pain should only be performed by well-trained physicians under fluoroscopic guidance.

Epidural injections for the treatment of chronic pain should only be performed by well-trained physicians under fluoroscopic guidance. American Society of Regional Anesthesia guidelines should be consulted before neuraxial interventions on patients receiving anticoagulants. However, it is important to recognize these guidelines do not specifically address interventional pain procedures.

American Society of Regional Anesthesia guidelines should be consulted before neuraxial interventions on patients receiving anticoagulants. However, it is important to recognize these guidelines do not specifically address interventional pain procedures.Introduction

Epidural steroid injections (ESIs) have been associated with a myriad of complications and side effects. Although the overall incidence of complications from ESIs appears to be low,1 there are some potentially catastrophic complications that should be considered by all physicians performing these procedures. There are two general categories of complications associated with ESIs: exogenous steroid side effects and complications associated with the actual placement of the needle by the physician performing the procedure. Complications associated with ESIs are discussed in this chapter and are organized into medication-associated complications and those complications that may result from the procedure.

Complications of Steroid Administration

Complications that may result from corticosteroid injections include hyperglycemia, Cushing syndrome, hypertension, deep venous thrombosis (DVT), secondary infections, psychological disorders, lipid accumulation (epidural lipomatosis), osteoporosis, vertebral compression fractures, avascular necrosis of joints, and numerous other endocrine and dermatologic manifestations.2 Epidural steroid administration has been demonstrated to adversely affect native cortisol concentrations for up to 30 days from a single injection.3 It is likely that suppression of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis is variable among individuals, but there is evidence that a series of three epidural injections with 40 mg of triamcinolone may suppress the HPA axis for up to 3 months.2 Serious side effects such as steroid myopathy and Cushing syndrome have been reported after a single epidural dose of triamcinolone.4 Although the risk of complications from ESIs theoretically should increase with increasing frequency of injections, it appears that total dose of steroids given during a specific time may be more important in determining steroid complications.5,6

Recommendations for Avoiding Steroid Complications

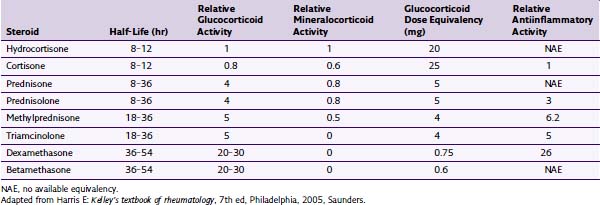

The total annual dose of steroid should be limited to the smallest efficacious dose. Although there is insufficient evidence to determine the risks of epidural steroid administration, evidence suggests that large annual doses of steroids may lead to serious complications. There is no evidence that large doses of steroids are superior to low doses. Recommendations have been made to limit the amount of annual steroid dose to 3 mg/kg of triamcinolone or equivalent.7 See Tables 13-1 and 13-2 for commercially available steroid preparations and their relative potencies.

| Steroid | Available Concentrations (mg/mL) | Typical Doses (mg) |

|---|---|---|

| Depo-Medrol (methylprednisolone) | 40, 80 | 40–80 |

| Celestone (betamethasone) | 6 | 6–12 |

| Kenalog (triamcinolone) | 25, 40 | 40–80 |

| Decadron (dexamethasone) | 4, 8 | 4–10 |

Adapted from Deer T, Ranson M, Kappural L, Diwan SA: Guidelines for the proper use of epidural steroid injections for the chronic pain patient, Tech Reg Anesth Pain Manage 13(4):288-295, 2009.

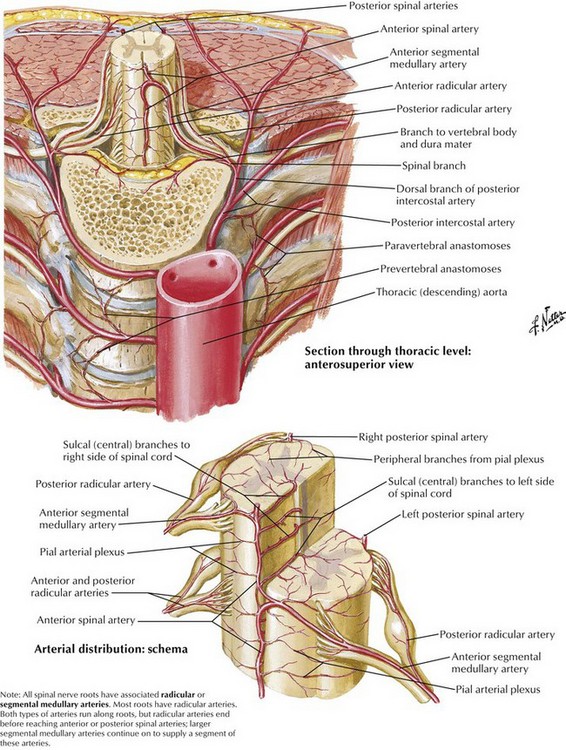

Transforaminal ESIs, especially in the cervical spine, have been reported to result in catastrophic complications, including stroke, paralysis, and death.8 Although there are more case reports of complications with transforaminal injections in the cervical spine, there are some reports of neurologic injury in the lumbar spine.9 Several mechanisms have been proposed for the development of anterior spinal artery syndrome, including mechanical trauma to a radicular artery supplying the anterior or posterior spinal arteries, vasospasm, and embolism resulting from particulate-containing steroids (Figs. 13-1 and 13-2).10,11 The use of nonparticulate steroids has been suggested to be safer than particulate steroids when performing cervical transforaminal injections.12 Cervical transforaminal injections should be approached with caution,7 and prudent physicians should consider using nonparticulate steroid solutions such as dexamethasone when performing transforaminal epidural injections in the thoracic and upper lumbar spine.

Complications Associated with Needle Placement and Injection

Numerous complications are associated with needle placement during epidural steroid administration. Pneumocephalus, pneumothorax, vascular injection, epidural hematoma, subdural injection, infection (localized skin, meningitis, and epidural abscess formation), nerve damage, spinal cord trauma, cerebrovascular infarction, DVT, vasovagal episodes, and increased pain have all been reported during both interlaminar and transforaminal approaches to the neuraxis.1 As with any invasive procedure, strict aseptic technique is mandatory. It has been reported that DuraPrep and alcohol-containing preparations are superior to iodine-containing antiseptic solutions in preventing infections.13 Although ChloraPrep and DuraPrep solutions are not approved for epidural and intrathecal use, iodine has never received Food and Drug Administration approval for epidural injections.

Several studies have reported that between 25% and 40% of epidural injections performed without fluoroscopy are not delivered to the intended target.14,15 Without the aid of fluoroscopy, the risk of intramuscular and inadvertent intrathecal injection may be substantially increased. Intrathecal injection can result in severe complications, including possible nerve injury from preservative-containing solutions, arachnoiditis, aseptic meningitis, cerebral vein thrombosis, adhesive arachnoiditis, and pneumocephaly.16,17

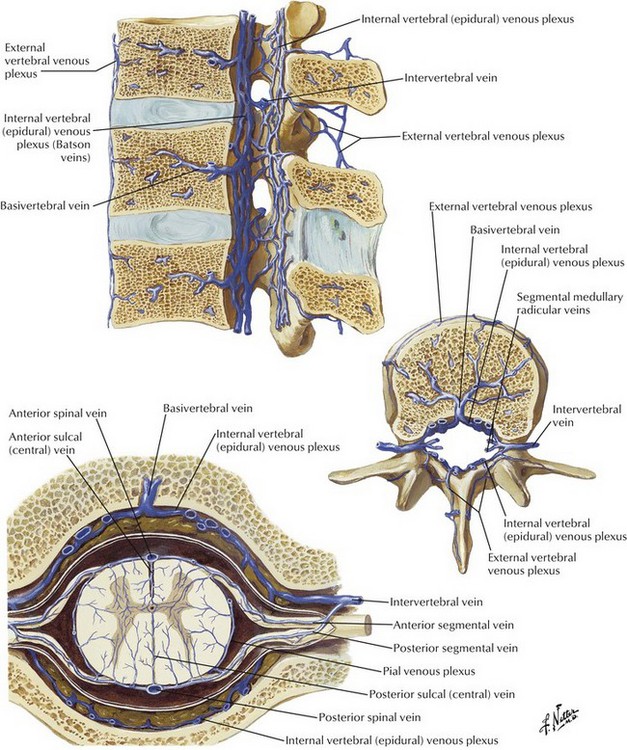

Transforaminal epidural injections are usually indicated in the treatment of radicular pain confined to one or two dermatomes.7 There have been numerous reports of catastrophic complications associated with the transforaminal approach with most of the case reports involving the cervical region.8,11 Most of the complications associated with the transforaminal approach have resulted in paralysis, presumably from anterior spinal syndrome, although smaller vessels and feeder arteries may also play a role. Although several mechanisms have been proposed for the development of anterior spinal artery syndrome, it is likely that the syndrome results from direct injury to a radicular artery or from embolism resulting from injection of high-particulate steroid into a radicular artery supplying the anterior spinal cord. Another proposed mechanism may be vasospasm without true embolism.10 Epidural hematoma formation is a significant but uncommon complication in patients receiving anticoagulation therapies (Fig. 13-3). Epidural hematoma formation has been estimated to occur in one in 150,000 to one in 220,000 patients undergoing neuraxial procedures.18 Although the risk of epidural hematoma in patients taking agents such as clopidogrel and warfarin seems well established, it is unclear when it is safe to perform ESIs in many of these patients. Discontinuing antifibrinolytic medications for 7 to 10 days has previously been recommended, but there are no data to establish when it is safe to perform neuraxial procedures in patients treated with these medications.19 Additionally, there has never been a clear relationship established between aspirin administration and epidural hematoma formation. Recommendations published by the American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Management (ASRA) attempt to provide guidelines for discontinuing anticoagulation in patients who are to undergo neuraxial procedures. These guidelines are based on the current scientific literature, but we will see many new drugs that impact clotting arising over the next few years, and these guidelines may not cover the new drugs appropriately.19 It is important to consult with the treating cardiologist or neurologist when these guidelines are not inclusive of the issue in question.

Recommendations for Avoiding Complications Associated with Needle Placement

Traditional injection techniques and targets to transforaminally access the epidural space have recently been challenged because injury to the artery of Adamkiewicz can be described as a “black swan” event. Furthermore, traditional needle trajectory and a target in the superior anterior portion of the foramen, directed to the “safe triangle,” places the needle tip anatomically where the vasculature resides, increasing the chance of vascular injury. To avoid potential vascular injury, some physicians recommend an inferior approach to the foramen, targeting the Kambin triangle.20

All epidural injections should be performed with fluoroscopy. Although there is no clear consensus regarding the use of contrast and digital subtraction fluoroscopy, it seems prudent to use contrast in all transforaminal procedures. Cervical transforaminal epidural injections have not been demonstrated to be more efficacious than the interlaminar approach and have resulted in significant injuries; therefore they should be used only in cases in which the risk is believed to be outweighed by the benefit. Low-particulate steroid compounds such as dexamethasone should be considered when entering the cervical, thoracic, or upper lumbar spine. No large prospective studies have compared nonparticulate steroids with particulate steroids in the treatment of patients with chronic pain, however, some are worth mentioning. A recent prospective, blinded study examined 61 patients randomly assigned to either particulate or nonparticulate steroids of equipotent doses to treat lumbar radicular pain, examining VAS, complications, medication adjustments, and additional therapeutic interventions. The investigators concluded that nonparticulate steroid is very comparable to safety and effectiveness as particulate steroid for the treatment of lumbar radicular pain, with a statistically nonsignificant trend of less lengthy pain relief and magnitude.21 Similarly, another prospective randomized study compared equipotent particulate versus nonparticulate steroid injections in 106 patients with lumbar radiculopathy, concluding that nonstatistically significant differences were determined for McGill Pain Questionnaire, or the Oswestry Disability Index, where a statistically significant difference was apparent for the VAS (visual analog scale) in favor of particulate steroid injections.22

Conclusion

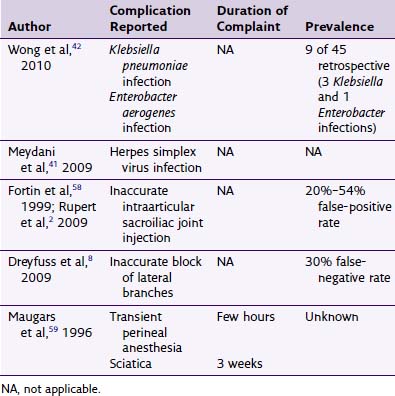

Conscientious physicians perform ESIs only on patients who have been thoroughly evaluated and have undergone all appropriate laboratory evaluations, including coagulation studies if indicated. ESIs should only be performed by qualified physicians who have the proper training to perform these procedures safely and properly with fluoroscopic guidance. Ultrasonography is emerging and may be an alternative to fluoroscopy in the future. Serious complications and death have been reported from epidural steroid administration (Table 13-3). Physicians who have not completed residency or fellowship training that included interventional pain management training are strongly encouraged to pursue postgraduate training in an accredited fellowship program in interventional pain management before performing ESIs.

Table 13-3 Complications Reported from Epidural Steroid Administration

1 Abdi S, Datta S, Lucas LF. Role of epidural steroids in the management of chronic spinal pain: a systematic review of effectiveness and complications. Pain Physician. 2005;8(1):127-143.

2 Manchikanti L. Role of neuraxial steroids in interventional pain management. Pain Physician. 2002;5(2):182-199.

3 Dubois EF, Wagemans MF, Verdouw BC, et al. Lack of relationships between cumulative methylprednisolone dose and bone mineral density in healthy men and postmenopausal women with chronic low back pain. Clin Rheumatol. 2003;22(1):12-17.

4 Boonen S, Van Distel G, Westhovens R, Dequeker J. Steroid myopathy induced by epidural triamcinolone injection. Br J Rheumatol. 1995;34(4):385-386.

5 Knight CL, Burnell JC. Systemic side-effects of extradural steroids. Anaesthesia. 1980;35(6):593-594.

6 Kay J, Findling JW, Raff H. Epidural triamcinolone suppresses the pituitary-adrenal axis in human subjects. Anesth Analg. 1994;79(3):501-505.

7 Deer T, Ranson M, Kappural L, Diwan SA. Guidelines for the proper use of epidural steroid injections for the chronic pain patient. Tech Reg Anesth Pain Manage. 2009;13(4):288-295.

8 Scanlon GC, Moeller-Bertram T, Romanowsky SM, Wallace MS. Cervical transforaminal epidural steroid injections: more dangerous than we think? Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2007;32(11):1249-1256.

9 Huntoon MA Martin DP. Paralysis after transforaminal epidural injection and previous spinal surgery. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2004;29(5):494-495.

10 Baker R, Dreyfuss P, Mercer S, Bogduk N. Cervical transforaminal injection of corticosteroids into a radicular artery: a possible mechanism for spinal cord injury. Pain. 2003;103(1-2):211-215.

11 Rathmell JP, Aprill C, Bogduk N. Cervical transforaminal injection of steroids. Anesthesiology. 2004;100(6):1595-1600.

12 Anwar A, Zaidah I, Rozita R. Prospective randomized single blind study of epidural steroid injection comparing triamcinolone acetonide with methylprednisolone acetate. APLAR J Rheumatol. 2005;8:1-53.

13 Birnbach DJ, Meadows W, Stein DJ, et al. Comparison of povidone iodine and DuraPrep, an iodophor-in-isopropyl alcohol solution, for skin disinfection prior to epidural catheter insertion in parturients. Anesthesiology. 2003;98(1):164-169.

14 White AH, Derby R, Wynne G. Epidural injections for the diagnosis and treatment of low-back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1980;5(1):78-86.

15 White AH. Injection techniques for the diagnosis and treatment of low back pain. Orthop Clin North Am. 1983;14(3):553-567.

16 Abram SE. Intrathecal steroid injection for postherpetic neuralgia: what are the risks? Reg Anesth Pain Med. 1999;24(4):283-285.

17 Mateo E, López-Alarcón MD, Moliner S, et al. Epidural and subarachnoidal pneumocephalus after epidural technique. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 1999;16(6):413-417.

18 Tryba M. [Epidural regional anesthesia and low molecular heparin: Pro]. Anasthesiol Intensivmed Notfallmed Schmerzther. 1993;28(3):179-181.

19 Horlocker TT, Wedel DJ, Benzon H, et al. Regional anesthesia in the anticoagulated patient: defining the risks (the second ASRA Consensus Conference on Neuraxial Anesthesia and Anticoagulation). Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2003;28(3):172-197.

20 Glaser SE, Shah RV. Root cause analysis of paraplegia following transforaminal epidural injections: the unsafe triangle. Pain Physician. 2010;13:237-244.

21 Kim D, Brown J. Efficacy and safety of lumbar epidural dexamethasone versus methylprednisolone in the treatment of lumbar radiculopathy: A comparison of soluble versus particulate steroids. Clin J Pain. 2011;27:518-522.

22 Park CH, Lee SH, Kim BI. Comparison of effectiveness of lumbar transforaminal epidural injection with particulate and nonparticulate corticosteroids in lumbar radiating pain. Pain Medicine. 2010;11:1654-1658.