Chapter 12 Complications Associated with Head and Neck Blocks, Upper Extremity Blocks, Lower Extremity Blocks, and Differential Diagnostic Blocks

Procedures should only be performed by or under the direct supervision of those who have subspecialty training in interventional pain management.

Procedures should only be performed by or under the direct supervision of those who have subspecialty training in interventional pain management. Development of standardized procedural approaches, including preprocedure timeouts and sterile techniques, may decrease the likelihood of adverse events.

Development of standardized procedural approaches, including preprocedure timeouts and sterile techniques, may decrease the likelihood of adverse events.Introduction

As with any medical procedure, the physician performing the procedure should weigh the benefits versus the risks. Interventional procedures have significant potential benefit for those suffering from chronic pain. Although uncommon, complications may result in catastrophic outcomes. This chapter reviews the complications associated with a diverse group of procedures, including head and neck blocks, upper extremity blocks, lower extremity blocks, and differential diagnostic blocks. The complications associated with these can generally be divided into vascular, infectious, neural, pharmacologic, and anatomically related to the specific sight of injection (Table 12-1).

Table 12-1 Overview of Complications Associated with Head and Neck Block, Upper Extremity Block, Lower Extremity Block, and Differential Diagnostic Block Procedures

| Vascular1–6 |

CNS, central nervous system.

Vascular

Many neural structures are intimately connected with vasculature. Overall, the likelihood of a vascular complication is rare but potentially devastating. Reported vascular complications include airway, neural, and microvascular compression related to hematoma formation.1–3 Additionally, arterial dissection, pseudoaneurysm, and vascular insufficiency secondary to vasospasm have all been cited in the literature.4–6

Infection

The likelihood of infection from any single injection is extremely rare. Infection requiring intervention after an indwelling catheter has been reported as high as 0.8%.7 With interventional procedures involving the neuraxis, terrible sequelae, including epidural abscess or meningitis, may occur. Evidence demonstrates that catheter insertion (particularly >48 hours), intensive care unit admission, male sex, lack of prophylactic antibiotics, and lack of provider experience increase the likelihood of infection.8

Local Anesthetic Toxicity

The proximity of many neural structures to major vessels predisposes itself to the potential for local anesthetic toxicity. Inadvertent vascular puncture is the most likely cause of toxicity, but it has been suggested that with no identifiable puncture, clinical doses may cause toxicity.9 It appears that clinically significant local anesthetic toxicity occurs between 7.5 and 20 times per 10000 regional anesthetics.10 Local anesthetic toxicity can be categorized by symptoms involving the central nervous system (CNS) and those related to cardiovascular toxicity (Table 12-2).

Table 12-2 Signs and Symptoms Associated with Local Anesthetic Toxicity

| Central nervous system11 |

CNS, central nervous system.

Neurologic

The likelihood of long-term neurologic injury is low, reported below 0.02%.13 When these injuries do occur, the outcome is often devastating to the clinician and patient alike. Nerve injury may present in a spectrum from paresthesias to paralysis, with neuropathic pain being a dreaded outcome.

Etiologies attributed to nerve injury include direct needle trauma, barotrauma from high-pressure injection, compression from hematoma, and local anesthetic neural toxicity.2,14–16

Complications of Head and Neck Blocks

A variety of percutaneous techniques are available for targets at head and neck, including sphenopalatine ganglion (SPG), Gasserian ganglion, atlantoaxial joint (AAJ) and atlantooccipital joint (AOJ), stellate ganglion, and C2 dorsal root ganglion. See Table 12-3 for a description of complications associated with head and neck injections.

Table 12-3 Common Head and Neck Blocks with Associated Complications

| Gasserian ganglion block and neurolysis17,32 |

AAJ, atlantoaxial joint; AOJ, atlantooccipital joint; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; PPF, pterygopalatine fossa; RFA, radiofrequency ablation; SPG, sphenopalatine ganglion.

Gasserian Ganglion Block and Neurolysis

The Gasserian (trigeminal) ganglion lies within the Meckel cave, which contains cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), and local anesthetic deposited in this area may spread to other cranial nerves and can potentially cause brainstem anesthesia.17 Infection, CSF leak, bleeding, and nerve damage are also likely with Gasserian ganglion block or ablation because it is located in the middle of the brain surrounded by blood vessels. Literature studies show that RFA of the Gasserian ganglion is associated with the highest incidence of complications, with nearly one-third of patients developing some form of complications.18 Postoperative trigeminal sensory loss affects virtually all patients treated with RFA, and it is considered a side effect rather than a complication.

Sphenopalatine Ganglion Block

Epistaxis is more frequent with an intranasal approach to SPG block; intravascular injection or hematoma formation can occur after maxillary artery injury, which lies within the pterygopalatine fossa (PPF). Cheek hematoma is the most common complication. Infection is always possible especially with inadvertent needle entry into the nasal or oral cavity.19 Reflex bradycardia is likely with RFA because of the rich parasympathetic connections to the SPG.20 RFA of the SPG can result in permanent or temporary hyperesthesia or dysesthesia in the palate, maxilla, or posterior pharynx.21–23 Temporary diplopia, which is more common after local anesthetic injections rather than RFA, is caused by the spread of the injectate from the PPF to the inferior orbital fissure containing the abducent nerve.24 Temporary diplopia is likely if the needle tip is deep inside the PPF and the volume of injectate is greater than 1 to 2 mL.

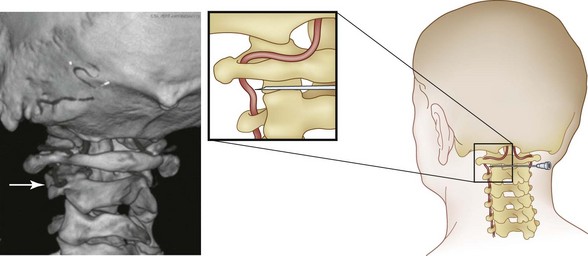

Atlantoaxial Joint and Atlantooccipital Joint Injections

The AAJ and AOJ are in very close proximity to the vertebral artery (Fig. 12-1). Consequently, particular attention should be paid to avoid intravascular injection because vertebral artery anatomy can be unpredictable. Intraarterial injection may cause seizure or posterior circulation stroke.25 Inadvertent puncture of the C2 dural sleeve with CSF leak or high spinal spread of the local anesthetic may occur with AAJ injection if the needle is directed too medially. This can result in a rapid and profound decrease in blood pressure followed by apnea and death. Therefore, intravenous access should be established before the procedure. Spinal cord injury and syringomyelia are potential serious complications if the needle is directed even further medially.19

Stellate Ganglion Block

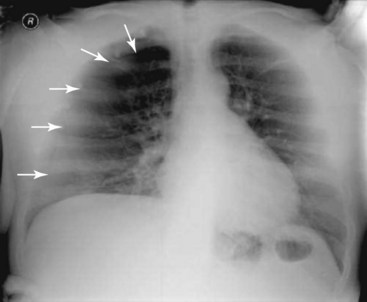

Many important structures lie close to the stellate ganglion. Hence, technical complications from injury to the nerves and viscera are possible during insertion of the needle.17,26,27 This includes injury to the brachial plexus; trauma to the trachea and esophagus; injury to the pleura and lung (pneumothorax, hemothorax, which may require chest tube insertion); and bleeding and local hematoma, especially if the patient was taking anticoagulants. This can lead to airway compression (Fig. 12-2).28,29 Vasovagal attacks can also occur, especially with inadvertent manipulation of carotid sinus during the block. Infectious complications are possible if there was a breach in the aseptic barrier. These can include local abscess, cellulitis, and osteitis of the vertebral body and transverse process.30

Complications related to the injectates include dose, volume, type of local anesthetic and site of deposition of the solution. Accidental block of the recurrent laryngeal nerve can cause hoarseness of voice while phrenic nerve paralysis can lead to respiratory depression especially if there is contralateral dysfunction of the phrenic nerve, or in patients with a preexisting respiratory problem. Therefore, bilateral stellate ganglia block is generally not recommended.17,26 Intraarterial injection into the vertebral artery or the carotid artery can produce a high concentration of local anesthetic agent in the CNS, leading to seizures. Intravenous injection can also lead to seizure, if a high volume of local anesthetic is used.17 Medial epidural spread and intrathecal injection of local anesthetic, producing high spinal blockade, has also been documented. Horner syndrome is often the final consequence of sympathetic blockade; although not a complication, it can be unpleasant. Air embolism has also been reported. Loss of cardioaccelerator activity may lead to various bradyarrhythmias and hypotension.17

Complications from RFA are similar to the complications produced by local anesthetic sympathetic ganglia block, with the exception of a longer lasting block and potential neuritis. Because of an increased chance of injury to the surrounding structures, phenol or alcohol neurolysis is not recommended.31

Complications of Upper Extremity Blocks

Upper extremity blockade is most commonly performed in the perioperative environment for intraoperative and postoperative analgesia. Physicians performing these procedures should consider the use of ultrasound to minimize the risks associated with peripheral nerve blocks. The majority of literature regarding this blockade comes from practitioners of regional anesthesia. However, upper extremity blockade may be a useful tool to the pain clinician for treatment and diagnosis. In the case of upper extremity neural blockade, complications can generally be divided into vascular, infectious, neural, local anesthetic toxicity, and anatomically related to the specific site of injection (Table 12-4). A large French study has reported that the overall incidence of serious complication from peripheral nerve block is 0.04%.13

Table 12-4 Upper Extremity Blocks and Their Site-Specific Advantages and Complications

| Interscalene block44–49 |

The brachial plexus is intimately connected with a variety of vascular structures. Overall, the likelihood of a vascular complication is rare but potentially devastating. Reported vascular complications include hematoma, resulting in airway, neural, and microvascular compression.1–3 Arterial dissection, pseudoaneurysm, and vascular insufficiency secondary to vasospasm have also been reported.4–6

The likelihood of long-term neural injury is low, reported below 0.02%.13 When these injuries do occur, the outcome is often devastating to the clinician and patient alike. Nerve injury may present in a spectrum of paresthesias, paralysis, and neuropathic pain.

The proximity of the brachial plexus to major vascular structures predisposes itself to the potential for local anesthetic toxicity. Inadvertent vascular puncture is the most likely cause of toxicity, but it has been suggested that even with no identifiable puncture clinical doses may cause toxicity.9 Clinically significant local anesthetic toxicity occurs between 7.5 and 20 times per 10,000 regional anesthetics.10

Interscalene Block

The approach at the interscalene level carries the greatest anatomic risk because it is adjacent to many central structures. Some reports state a complication rate as high as 1.1%35 This approach yields an almost 100% incidence of unilateral phrenic nerve palsy (Fig. 12-3) and should be used with caution in those with respiratory insufficiency.36

Supraclavicular Block

The supraclavicular nerve block has the advantage of being slightly farther away from the central and neuraxial structures but does consistently miss the long thoracic and dorsal scapular nerves and may miss the subclavius and suprascapular nerves, all of which may be important to complete shoulder blockade.3 It does, however, remain close enough that local anesthesia spread involves the phrenic nerve in about 50% of patients.37 Additionally, reports have shown transient Horner syndrome and recurrent laryngeal involvement with this approach.38,39 It has been suggested that there is an increased likelihood of pneumothorax with this approach compared with the infraclavicular approach (Fig. 12-4).40,41

Infraclavicular Block

Similarly to the axillary block, the infraclavicular approach is some distance from central and neuraxial structures. This provides some decreased risk of anatomically related complications. It must be kept in mind that the pleural space is close to the neurovascular bundle at this level, and pneumothoraces have been reported.42,43

Axillary Block

The axillary injection site for brachial plexus blockade carries the least risk for structural injury and complication because of its distance from centroneuraxis structures. The one potential complication that some authors suggest is an increased potential for vascular uptake of the medication because of an increase in distance between intended neural structures, with most providers using a “fanlike” needle technique for injection.37

Complications of Lower Extremity Blocks

The incidence of nerve injury after neural block is very low.50 An observational study demonstrated a 1.7% incidence of post-operative neurologic dysfunction after 3996 nerve blocks performed with multiple injection techniques.51 Complications of lower extremity blocks share many characteristics that are similar from one to another (Table 12-5). The complications could be simply separated as local complications and systemic complications.

Table 12-5 Specific Complications Following Lower Limb Nerve Block

| Psoas compartment block57–60 |

Local complications include nerve damage and injury to surrounding anatomic structures. Nerve puncture by the block needle and intraneural injection of local anesthetic is a feared complication and is thought to be a major contributor to neurologic injury after peripheral nerve blocks.52 High injection pressure has also been postulated as a cause of neural injury.15 Fortunately, it has been shown that injection of local anesthetics beyond the epineurium does not result in nerve damage.52,53 Paresthesia or dysesthesia without motor deficit may be attributable to injury of the nervi nervorum, which innervate the epineurium and mesoneurium.52 Leakage around the puncture site, especially when a catheter has been introduced, may favor bacterial contamination. Furthermore, infection may be a result of inadequate sterilization and might result in sepsis or CNS infection. The local complications are avoidable with adequate imaging modalities and applying standard operating procedures. Leakage around the catheter can be reduced by tunneling the catheter and applying a slightly compressive dressing.

Systemic complications usually result from accidental intravascular injection of local anesthetics; less frequently, overzealous administration has been implicated.54,55 These complications can be life threatening, and both adults and children should be managed in the same way. The major difference between adults and children is that cardiovascular complications are often not preceded by neurologic signs but are concomitant with cerebral toxicity.56 The incidence of systemic reactions to local anesthetics ranges between 3.9 and 11 in 10,000.50

Psoas Compartment Block (Posterior Approach to the Lumbar Plexus)

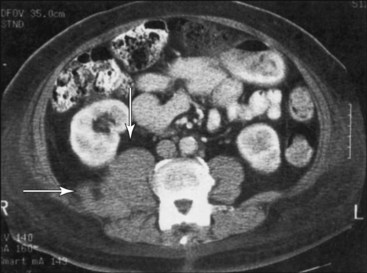

Because of the anatomic location, blind technique in this region carries the potential for intrathecal injection with resulting total spinal anesthesia, large-volume injections are commonly associated with epidural spread with volumes greater than 20 mL.57–60 Peripheral nerve damage and sympathetic block from extravasation of local anesthetic are also reported with the paravertebral approach. Furthermore, case reports exist of retroperitoneal hematomas with associated lumbar plexopathies (Fig. 12-5).61

Lumbar Sympathetic Block

The lumbar sympathetic block is used for a variety of lower extremity sympathetically mediated disorders. Similar to the stellate ganglion block, complications related to this procedure are best characterized as anatomic, drug-related, or infectious. Traversing the lumbar roots for this procedure increases the likelihood of lumbar root injury. Furthermore, the close proximity of the lumbar plexus to major vessels increases the likelihood of vascular puncture.62 Anatomic knowledge in combination with image guidance in this region is paramount because injury to vital structures, including renal and ureteral trauma, have been reported.63,64 Furthermore, local anesthetic toxicity and intrathecal blocks have been reported.65

Perivascular Three-in-One (Femoral) Nerve Block

Femoral nerve block is frequently used in the perioperative period by regional anesthesiologists for analgesia with total knee replacements.66 Complications related to this procedure include intravascular injection, hematoma, and nerve damage, all being reported infrequently.13

Lateral Femoral Cutaneous Nerve Block

Meralgia paresthetica is a neurologic disorder of the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve characterized by pain and paresthesia of the anterior lateral thigh. Blockade of the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve is often used more for diagnostic purposes rather than treatment. Complications of this block are rarely reported. It is recommended that ultrasonography be used for this procedure not only to minimize complication but also because of the high incidence of anatomic variation(≤25%).67

Sciatic Nerve Block

Again, the sciatic nerve block is more commonly used by regional anesthesiologists than chronic pain practitioners. It is most commonly used for major foot and ankle surgery. It can also be helpful in diagnosis and treatment. Serious complications are rare but include muscle trauma and vascular puncture. Residual dysesthesias are frequently reported and usually last for 1 to 3 days with the remainder usually resolving within several months.51,68 Blockade of the sciatic nerve most commonly occurs in the subgluteal region (Labat approach) or within the popliteal fossa. It is advisable to use ultrasonography to decrease the chance of needle puncture of adjacent vital structures.

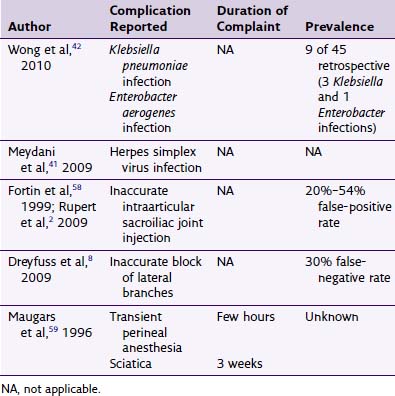

Differential Diagnostic Blocks

Differential diagnostic blocks are used to identify patients’ varying pain complaints and to differentiate among placebo-responsive pain, sympathetic pain, somatic pain, and central pain. The two main approaches to doing a diagnostic differential nerve block are intrathecal and epidural. There are also two techniques, the anatomic approach and the pharmacologic approach. The anatomic approach uses the anatomic separation of somatic and sympathetic nervous system fibers, and the pharmacologic approach uses different concentrations of local anesthetic to affect different types of fibers.64

Doing a differential diagnostic block through the epidural approach is generally more time consuming because it takes longer for the blocks to occur and may provide confounding results; however, risks are thought to be decreased with the epidural approach. The complications of performing epidural and spinal differential diagnostic blocks can be related (Box 12-1), the most dreaded being an epidural abscess (Fig. 12-6).64,65

1 Higa K, Hirata K, Hirota K, et al. Retropharyngeal hematoma after stellate ganglion block: Analysis of 27 patients reported in the literature. Anesthesiology. 2006;105:1238-1245. discussion 5A-6A

2 Ben-David B, Stahl S. Axillary block complicated by hematoma and radial nerve injury. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 1999;24:264-266.

3 Neal JM, Gerancher JC, Hebl JR, et al. Upper extremity regional anesthesia: essentials of our current understanding, 2008. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2009;34:134-170.

4 Bhat R. Transient vascular insufficiency after axillary brachial plexus block in a child. Anesth Analg. 2004;98:1284-1285. table of contents

5 Ott B, Neuberger L, Frey HP. Obliteration of the axillary artery after axillary block. Anaesthesia. 1989;44:773-774.

6 Flowers GA, Meyers JF. Pseudoaneurysm after interscalene block for a rotator cuff repair. Arthroscopy. 2004;20(suppl 2):67-69.

7 Neuburger M, Breitbarth J, Reisig F, et al. [Complications and adverse events in continuous peripheral regional anesthesia: results of investigations on 3,491 catheters]. Anaesthesist. 2006;55:33-40.

8 Capdevila X, Pirat P, Bringuier S, et al. Continuous peripheral nerve blocks in hospital wards after orthopedic surgery: a multicenter prospective analysis of the quality of postoperative analgesia and complications in 1,416 patients. Anesthesiology. 2005;103:1035-1045.

9 Dhir S, Ganapathy S, Lindsay P, Athwal GS. Case report: ropivacaine neurotoxicity at clinical doses in interscalene brachial plexus block. Can J Anaesth. 2007;54:912-916.

10 Mulroy MF. Systemic toxicity and cardiotoxicity from local anesthetics: incidence and preventive measures. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2002;27:556-561.

11 Dillane D, Finucane BT. Local anesthetic systemic toxicity. Can J Anaesth. 2010;57:368-380.

12 Finucane BT. Complications of regional anesthesia, ed 2. New York, NY: Springer; 2007.

13 Auroy Y, Benhamou D, Bargues L, et al. Major complications of regional anesthesia in France. The SOS Regional Anesthesia Hotline Service. Anesthesiology. 2002;97:6.

14 Rice AS, McMahon SB. Peripheral nerve injury caused by injection needles used in regional anaesthesia: influence of bevel configuration, studied in a rat model. Br J Anaesth. 1992;69:433-438.

15 Hadzic A, Dilberovic F, Shah S, et al. Combination of intraneural injection and high injection pressure leads to fascicular injury and neurologic deficits in dogs. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2004;29:417-423.

16 Hogan QH. Pathophysiology of peripheral nerve injury during regional anesthesia. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2008;33:435-441.

17 Bridenbaugh PO, Cousins MJ. Neural blockade in clinical anesthesia and management of pain, ed 3. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven; 1998.

18 Lopez BC, Hamlyn PJ, Zakrzewska JM. Systematic review of ablative neurosurgical techniques for the treatment of trigeminal neuralgia. Neurosurgery. 2004;54:973-982. discussion 982-983

19 Narouze S. Complications of head and neck procedures. Tech Reg Anesth Pain Manage. 2007;11:6.

20 Konen A. Unexpected effects due to radiofrequency thermocoagulation of the sphenopalatine ganglion: two case reports. Pain Digest. 2000;10:3.

21 Salar G, Ori C, Iob I, Fiore D. Percutaneous thermocoagulation for sphenopalatine ganglion neuralgia. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1987;84:24-28.

22 Sanders M, Zuurmond WW. Efficacy of sphenopalatine ganglion blockade in 66 patients suffering from cluster headache: a 12- to 70-month follow-up evaluation. J Neurosurg. 1997;87:876-880.

23 Narouze S, Kapural L, Casanova J, Mekhail N. Sphenopalatine ganglion radiofrequency ablation for the management of chronic cluster headache. Headache. 2009;49:571-577.

24 Narouze SN. Role of sphenopalatine ganglion neuroablation in the management of cluster headache. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2010;14:160-163.

25 Edlow BL, Wainger BJ, Frosch MP, et al. Posterior circulation stroke after C1-C2 intraarticular facet steroid injection: evidence for diffuse microvascular injury. Anesthesiology. 2010;112:1532-1535.

26 Bonica JJ. The management of pain, ed 2. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger; 1990.

27 Hogan QH, Abram SE. Neural blockade for diagnosis and prognosis. A review. Anesthesiology. 1997;86:216-241.

28 Elias M, Chakerian M. Repeated stellate ganglion blockade using a catheter for pediatric herpes zoster ophthalmicus. Anesthesiology. 1994;80:2.

29 Mishio M, Matsumoto T, Okuda Y, Kitajima T. Delayed severe airway obstruction due to hematoma following stellate ganglion block. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 1998;23:516-519.

30 Hartzler GO, Osborn MJ. Invasive electrophysiological study in the Jervell and Lange-Nielsen syndrome. Br Heart J. 1981;45:225-229.

31 Elias M. Cervical sympathetic and stellate ganglion blocks. Pain Physician. 2000;3:294-304.

32 Zakrzewska JM, Jassim S, Bulman JS. A prospective, longitudinal study on patients with trigeminal neuralgia who underwent radiofrequency thermocoagulation of the Gasserian ganglion. Pain. 1999;79:51-58.

33 Narouze S, Vydyanathan A, Patel N. Ultrasound-guided stellate ganglion block successfully prevented esophageal puncture. Pain Physician. 2007;10:747-752.

34 Whitehurst L, Harrelson JM. Brain-stem anesthesia. An unusual complication of stellate ganglion block. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1977;59:541-542.

35 Lenters TR, Davies J, Matsen FA3rd. The types and severity of complications associated with interscalene brachial plexus block anesthesia: local and national evidence. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2007;16:379-387.

36 Cangiani L, Rezende L, Neto A. Phrenic Nerve block after interscalene brachial plexus block. Case report. Rev Bras Anestesiol. 2008;58:7.

37 Brown DL. Brachial plexus anesthesia: an analysis of options. Yale J Biol Med. 1993;66:415-431.

38 Solanki SL, Jain A, Makkar JK, Nikhar SA. Severe stridor and marked respiratory difficulty after right-sided supraclavicular brachial plexus block. J Anesth. 2011;25(2):305-307.

39 Perlas A, Lobo G, Lo N, et al. Ultrasound-guided supraclavicular block: outcome of 510 consecutive cases. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2009;34:171-176.

40 Yang CW, Kwon HU, Cho CK, et al. A comparison of infraclavicular and supraclavicular approaches to the brachial plexus using neurostimulation. Korean J Anesthesiol. 2010;58:260-266.

41 Bhatia A, Lai J, Chan VW, Brull R. Case report: pneumothorax as a complication of the ultrasound-guided supraclavicular approach for brachial plexus block. Anesth Analg. 2010;111:817-819.

42 Sanchez HB, Mariano ER, Abrams R, Meunier M. Pneumothorax following infraclavicular brachial plexus block for hand surgery. Orthopedics. 2008;31:709.

43 Crews JC, Gerancher JC, Weller RS. Pneumothorax after coracoid infraclavicular brachial plexus block. Anesth Analg. 2007;105:275-277.

44 Borgeat A, Ekatodramis G, Kalberer F, Benz C. Acute and nonacute complications associated with interscalene block and shoulder surgery: a prospective study. Anesthesiology. 2001;95:875-880.

45 Urmey WF, Talts KH, Sharrock NE. One hundred percent incidence of hemidiaphragmatic paresis associated with interscalene brachial plexus anesthesia as diagnosed by ultrasonography. Anesth Analg. 1991;72:498-503.

46 Seltzer JL. Hoarseness and Horner’s syndrome after interscalene brachial plexus block. Anesth Analg. 1977;56:585-586.

47 Sukhani R, Barclay J, Aasen M. Prolonged Horner’s syndrome after interscalene block: a management dilemma. Anesth Analg. 1994;79:601-603.

48 Walter M, Rogalla P, Spies C, et al. [Intrathecal misplacement of an interscalene plexus catheter]. Anaesthesist. 2005;54:215-219.

49 Faust A, Fournier R, Hagon O, et al. Partial sensory and motor deficit of ipsilateral lower limb after continuous interscalene brachial plexus block. Anesth Analg. 2006;102:288-290.

50 Auroy Y, Narchi P, Messiah A, et al. Serious complications related to regional anesthesia: results of a prospective survey in France. Anesthesiology. 1997;87:479-486.

51 Fanelli G, Casati A, Garancini P, Torri G. Nerve stimulator and multiple injection technique for upper and lower limb blockade: failure rate, patient acceptance, and neurologic complications. Study Group on Regional Anesthesia. Anesth Analg. 1999;88:847-852.

52 Bigeleisen PE. Nerve puncture and apparent intraneural injection during ultrasound-guided axillary block does not invariably result in neurologic injury. Anesthesiology. 2006;105:779-783.

53 Sala-Blanch X, Pomes J, Matute P, et al. Intraneural injection during anterior approach for sciatic nerve block. Anesthesiology. 2004;101:1027-1030.

54 Mazoit JX, Dalens BJ. Pharmacokinetics of local anaesthetics in infants and children. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2004;43:17-32.

55 D’Andrea P, Calabrese A, Grandolfo M. Intercellular calcium signalling between chondrocytes and synovial cells in co-culture. Biochem J. 1998;329(Pt 3):681-687.

56 Maxwell LG, Martin LD, Yaster M. Bupivacaine-induced cardiac toxicity in neonates: successful treatment with intravenous phenytoin. Anesthesiology. 1994;80:682-686.

57 Awad IT, Duggan EM. Posterior lumbar plexus block: anatomy, approaches, and techniques. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2005;30:143-149.

58 Capdevila X, Coimbra C, Choquet O. Approaches to the lumbar plexus: success, risks, and outcome. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2005;30:150-162.

59 Capdevila X, Macaire P, Dadure C, et al. Continuous psoas compartment block for postoperative analgesia after total hip arthroplasty: new landmarks, technical guidelines, and clinical evaluation. Anesth Analg. 2002;94:1606-1613. table of contents

60 Enneking FK, Chan V, Greger J, et al. Lower-extremity peripheral nerve blockade: essentials of our current understanding. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2005;30:4-35.

61 Klein SM, D’Ercole F, Greengrass RA, Warner DS. Enoxaparin associated with psoas hematoma and lumbar plexopathy after lumbar plexus block. Anesthesiology. 1997;87:1576-1579.

62 Haynsworth RFJr, Noe CE, Fassy LR. Intralymphatic injection: another complication of lumbar sympathetic block. Anesthesiology. 1994;80:460-462.

63 Wheatley JK, Motamedi F, Hammonds WD. Page kidney resulting from massive subcapsular hematoma. Complication of lumbar sympathetic nerve block. Urology. 1984;24:361-363.

64 Dirim A, Kumsar S. Iatrogenic ureteral injury due to lumbar sympathetic block. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 2008;42:395-396.

65 Gay GR, Evans JA. Total spinal anesthesia following lumbar paravertebral block: a potentially lethal complication. Anesth Analg. 1971;50:344-348.

66 Sharma S, Iorio R, Specht LM, et al. Complications of femoral nerve block for total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468:135-140.

67 Patijn J, Mekhail N, Hayek S, et al. Meralgia paresthetica. Pain Pract. 2011;11(3):302-308.

68 Auroy Y, Benhamou D, Bargues L, et al. Major complications of regional anesthesia in France: the SOS Regional Anesthesia Hotline Service. Anesthesiology. 2002;97:1274-1280.