11 Complications and legal considerations of laser and light treatments

General complications

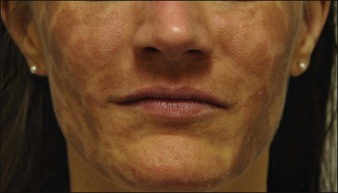

Hyperpigmentation (Fig. 11.1) is a very common complication and possibly the most common in darker skin types (see the study by Sriprachya-anunt and colleagues). It has been described with the use of almost every laser and light device in darker skin types. In one study by Moreno-Arias and co-workers, it was observed in 16% of patients undergoing IPL treatment. Goh reported that it can be as high as 45% in patients with skin types IV–VI. Wareham et al reported that the pulse dye laser can cause hyperpigmentation, especially on the lower legs and where there is inadequate post-treatment sun protection and sun avoidance. Hyperpigmentation was also seen by Chowdhury and colleagues with the KTP laser. With the ablative CO2 laser, post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation (PIH) is common and was reported by Badawi et al to occur in 20–30% of Fitzpatrick III and 100% of Fitzpatrick IV patients. Mahmoud et al found the Er : YAG laser to have a PIH rate of 50% in patients with skin type IV–V (Fig. 11.2). Even non-ablative fractional lasers can cause problems with PIH; in a 2010 study by Chan et al there was an 18.2% rate in 47 patients treated. Although rarer, PIH has also been reported (e.g. by Choudhary et al and Kuperman-Beade et al) to occur with the use of Q-switched lasers. In darker skin types, it can be fairly common; it was reported by Lapidoth & Aharonowitz to occur in up to 44% of darker-skinned patients. As noted above, vascular lasers were also found by Clark et al to result in PIH, albeit more rarely.

Figure 11.1 Post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation following treatment with the Q-switched Nd : YAG laser.

Scarring has been reported with almost every cutaneous laser and light source (Figs 11.3–11.6). The actual incidence is fairly small, yet overaggressive treatment with any laser or light device can cause it. Hypertrophic scarring is most common with the older continuous wave lasers, most of which are no longer commonly used in office practice.

Specific laser complications

Q-switched lasers

In the study by Kuperman-Beade and co-workers, the most common adverse effects of the Q-switched lasers included hypo- and hyperpigmentation, textural change, and scarring after treatment (see Fig. 11.1). Melanin is the main competing chromophore and transient hypopigmentation as well as permanent depigmentation with the Q-switched ruby laser can be seen (see the study above and those by Bernstein and Choudhary et al). Grevelink et al found that the Q-switched Nd : YAG laser with its longer wavelength has less chance of hypopigmentation than the Q-switched ruby laser. In darker-skinned individuals, if a Q-switched laser other than the Nd : YAG laser is used then decreasing the fluence may help prevent hypopigmentation, according to Kuperman-Beade et al.

Vascular lasers

The vascular lasers have become safer over time. The advent of pulsed rather than continuous lasers, better cooling technology, and the understanding of selective photothermolysis have advanced the safety profile tremendously. However, there are still a few complications commonly seen. Purpura is expected with the use of the pulse dye laser with short pulse durations and high fluences. Iyer & Fitzpatrick reported that lower fluences with multiple passes or cautious pulse stacking can be performed to achieve similar results without purpura. Long pulse durations can also eliminate post-treatment purpura. Rarely, there can be textural change, with an incidence of less than 1% in the treatment of port-wine stains in the studies by Kono et al and Levine & Geronemus (see Fig. 11.3). The latter also found that PIH can be common if there is sunlight exposure post-treatment, so sun avoidance or protection needs to be utilized. Older vascular lasers had a much higher incidence of complications, with the argon laser notorious for causing atrophic hypopigmented scars. Olbricht and colleagues found another notable complication with the argon laser was hypertrophic scarring and prolonged wound healing.

IPL-specific complications

IPL treatment is very well tolerated in general, but it has a higher learning curve with an increased number of variables. These variables include filters, pulse duration, fluence, the ability to double or triple pulse, and a variety of indications. Crusting and blistering occur in approximately 2–16% of patients; further, persistent local heat sensation lasting longer than 24 hours occur in 2% of patients. A rare complication of IPL treatment seen by Vlachos & Kontoes was the development of terminal hairs within a treated port-wine stain. Scarring has been only rarely reported (see the studies by Ho et al and Raulin et al and Fig. 11.6). Treatment of tanned patients can produce obvious hypopigmentation. Paradoxical hair growth has been reported (by Babilas et al, and Moreno-Arias et al), along with transient hypopigmentation and post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation especially in patients with darker skin and Mediterranean or middle-eastern background. Leukotrichia was also found to develop, along with temporary color change from black to yellow color, in studies by Radmanesh et al.

Legal aspects

1. The witness’ personal practice and / or

2. The practice of others that he has observed in his experience; and / or

3. Medical literature in recognized publications; and / or

4. Statutes and / or legislative rules; and / or

5. Courses where the subject is discussed and taught in a well-defined manner.

Accreditation Association for Ambulatory Health Care. Accreditation handbook for ambulatory healthcare. Wilmette, IL: Accreditation Association for Ambulatory Health Care; 2000.

Adamic M, Troilius A, Adatto M, et al. Vascular lasers and IPLS: guidelines for care from the European Society for Laser Dermatology (ESLD). Journal of Cosmetic and Laser Therapy. 2007;9(2):113–124.

Alam M, et al. A prospective trial of fungal colonization after laser resurfacing of the face: correlation between culture positivity and symptoms of pruritus. Dermatologic Surgery. 2003;29(3):255–260.

Alster TS, Lupton JR. Prevention and treatment of side effects and complications of cutaneous laser resurfacing. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 2002;109(1):308–316. discussion 317-318

Anvari B, et al. A comparative study of human skin thermal response to sapphire contact and cryogen spray cooling. IEEE Transactions Biomedical Engineering. 1998;45(7):934–941.

Ashinoff R, Levine VJ, Soter NA. Allergic reactions to tattoo pigment after laser treatment. Dermatologic Surgery. 1995;21(4):291–294.

Avram MM, et al. Hypertrophic scarring of the neck following ablative fractional carbon dioxide laser resurfacing. Lasers in Surgery and Medicine. 2009;41(3):185–188.

Babilas P, et al. Intense pulsed light (IPL): a review. Lasers in Surgery and Medicine. 2010;42(2):93–104.

Badawi A, et al. Retrospective analysis of non-ablative scar treatment in dark skin types using the sub-millisecond Nd : YAG 1,064 nm laser. Lasers in Surgery and Medicine. 2011;43(2):130–136.

Bernstein EF. Laser treatment of tattoos. Clinical Dermatology. 2006;24(1):43–55.

Bernstein LJ, et al. The short- and long-term side effects of carbon dioxide laser resurfacing. Dermatologic Surgery. 1997;23(7):519–525.

Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP, 2nd edn. Dermatology, Mosby Elsevier, Philadelphia, 2008;vol 2

Breadon JY, Barnes CA. Comparison of adverse events of laser and light-assisted hair removal systems in skin types IV-VI. Journal of Drugs in Dermatology. 2007;6(1):40–46.

Campbell TM, Goldman MP. Adverse events of fractionated carbon dioxide laser: review of 373 treatments. Dermatologic Surgery. 2010;36(11):1645–1650.

Casey AS, Goldberg D. Guidelines for laser hair removal. Journal of Cosmetic and Laser Therapy. 2008;10(1):24–33.

Chan HH, et al. Clinical application of lasers in Asians. Dermatologic Surgery. 2002;28(7):556–563.

Chan NP, et al. The use of non-ablative fractional resurfacing in Asian acne scar patients. Lasers in Surgery and Medicine. 2010;42(10):710–715.

Choudhary S, et al. Lasers for tattoo removal: a review. Lasers in Medical Science. 2010;25(5):619–627.

Chowdhury MM, Harris S, Lanigan SW. Potassium titanyl phosphate laser treatment of resistant port-wine stains. British Journal of Dermatology. 2001;144(4):814–817.

Clark C, et al. Treatment of superficial cutaneous vascular lesions: experience with the KTP 532 nm laser. Lasers in Medical Science. 2004;19(1):1–5.

Drosner M, Adatto M. Photo-epilation: guidelines for care from the European Society for Laser Dermatology (ESLD). Journal of Cosmetic and Laser Therapy. 2005;7(1):33–38.

England RW, Vogel P, Hagan L. Immediate cutaneous hypersensitivity after treatment of tattoo with Nd : YAG laser: a case report and review of the literature. Annals of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology. 2002;89(2):215–217.

Fitzpatrick RE, Goldman MP. Tattoo removal using the alexandrite laser. Archives of Dermatology. 1994;130(12):1508–1514.

Fitzpatrick RE, Lupton JR. Successful treatment of treatment-resistant laser-induced pigment darkening of a cosmetic tattoo. Lasers in Surgery and Medicine. 2000;27(4):358–361.

Furrow BF, Greaney TL, Johnson SH, Jost TS, et al. Liability in health care law, 3rd edn. St Paul, MN: West Publishing; 1997.

Goh CL. Comparative study on a single treatment response to long pulse Nd : YAG lasers and intense pulse light therapy for hair removal on skin type IV to VI – is longer wavelengths lasers preferred over shorter wavelengths lights for assisted hair removal. Journal of Dermatologic Treatment. 2003;14(4):243–247.

Goldberg DJ. Laser dermatology: pearls and problems. Oxford: Blackwell; 2007. p ix, 188

Graber EM, Tanzi EL, Alster TS. Side effects and complications of fractional laser photothermolysis: experience with 961 treatments. Dermatologic Surgery. 2008;34(3):301–305. discussion 305-307

Grevelink JM, et al. Laser treatment of tattoos in darkly pigmented patients: efficacy and side effects. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 1996;34(4):653–656.

Grimes PE, et al. Laser resurfacing-induced hypopigmentation: histologic alterations and repigmentation with topical photochemotherapy. Dermatologic Surgery. 2001;27(6):515–520.

Gundogan C, et al. [Repigmentation of persistent laser-induced hypopigmentation after tattoo ablation with the excimer laser]. Hautarzt. 2004;55(6):549–552.

Hardaway CA, Ross EV, Paithankar DY. Non-ablative cutaneous remodeling with a 1.45 microm mid-infrared diode laser: phase II. Journal of Cosmetic and Laser Therapy. 2002;4(1):9–14.

WS Ho, et al. Treatment of port wine stains with intense pulsed light: a prospective study. Dermatologic Surgery. 2004;30(6):887–890. discussion 890-891

WS Ho, et al. Use of onion extract, heparin, allantoin gel in prevention of scarring in Chinese patients having laser removal of tattoos: a prospective randomized controlled trial. Dermatologic Surgery. 2006;32(7):891–896.

Hunzeker CM, Weiss ET, Geronemus RG. Fractionated CO2 laser resurfacing: our experience with more than 2000 treatments. Aesthetic Surgery Journal. 2009;29(4):317–322.

Iyer S, Fitzpatrick RE. Long-pulsed dye laser treatment for facial telangiectasias and erythema: evaluation of a single purpuric pass versus multiple subpurpuric passes. Dermatologic Surgery. 2005;31(8 pt 1):898–903.

Izikson L, Avram M, Anderson RR. Transient immunoreactivity after laser tattoo removal: Report of two cases. Lasers in Surgery and Medicine. 2008;40(4):231–232.

Joint Commission International. Joint Commission International accreditation standards for ambulatory care, 2005. Oakbrook Terrace, IL: Joint Commission International; 2005. p v

Kauvar ANB, Hruza GJ. Principles and practices in cutaneous laser surgery. Boca Raton: Taylor & Francis; 2005. p 815

Kelly KM, et al. Cryogen spray cooling in combination with nonablative laser treatment of facial rhytides. Archives of Dermatology. 1999;135(6):691–694.

Khan R. Lasers in plastic surgery. Journal of Tissue Viability. 2001;11(3):103–107. 110-112

Kono T, et al. Comparison study of a traditional pulsed dye laser versus a long-pulsed dye laser in the treatment of early childhood hemangiomas. Lasers in Surgery and Medicine. 2006;38(2):112–115.

Kuperman-Beade M, Levine VJ, Ashinoff R. Laser removal of tattoos. American Journal of Clinical Dermatology. 2001;2(1):21–25.

Lapidoth M, Aharonowitz G. Tattoo removal among Ethiopian Jews in Israel: tradition faces technology. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2004;51(6):906–909.

Laubach HJ, et al. Skin responses to fractional photothermolysis. Lasers in Surgery and Medicine. 2006;38(2):142–149.

Levine VJ, Geronemus RG. Adverse effects associated with the 577- and 585-nanometer pulsed dye laser in the treatment of cutaneous vascular lesions: a study of 500 patients. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 1995;32(4):613–617.

Mahmoud BH, et al. Safety and efficacy of erbium-doped yttrium aluminum garnet fractionated laser for treatment of acne scars in type IV to VI skin. Dermatologic Surgery. 2010;36(5):602–609.

Manuskiatti W, Fitzpatrick RE, Goldman MP. Long-term effectiveness and side effects of carbon dioxide laser resurfacing for photoaged facial skin. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 1999;40(3):401–411.

Moreno-Arias GA, Castelo-Branco C, Ferrando J. Side-effects after IPL photodepilation. Dermatologic Surgery. 2002;28(12):1131–1134.

Nanni CA, Alster TS. Complications of carbon dioxide laser resurfacing. An evaluation of 500 patients. Dermatologic Surgery. 1998;24(3):315–320.

Neaman KC, et al. Outcomes of fractional CO2 laser application in aesthetic surgery: a retrospective review. Aesthetic Surgery Journal. 2010;30(6):845–852.

Nelson AA, Lask GP. Principles and practice of cutaneous laser and light therapy. Clinical Plastic Surgery. 2011;38(3):427–436.

Nelson JS, et al. Dynamic epidermal cooling during pulsed laser treatment of port-wine stain. A new methodology with preliminary clinical evaluation. Archives of Dermatology. 1995;131(6):695–700.

Nelson JS, et al. Dynamic epidermal cooling in conjunction with laser-induced photothermolysis of port wine stain blood vessels. Lasers in Surgery and Medicine. 1996;19(2):224–229.

Olbricht SM, et al. Complications of cutaneous laser surgery. A survey. Archives of Dermatology. 1987;123(3):345–349.

Prado A, et al. Full-face carbon dioxide laser resurfacing: a 10-year follow-up descriptive study. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 2008;121(3):983–993.

Rao J, Golden TA, Fitzpatrick RE. Atypical mycobacterial infection following blepharoplasty and full-face skin resurfacing with CO2 laser. Dermatologic Surgery. 2002;28(8):768–771. discussion 771

Radmanesh M, et al. Leukotrichia developed following application of intense pulsed light for hair removal. Dermatologic Surgery. 2002;28(7):572–574. discussion 574

Radmanesh M, et al. Burning, paradoxical hypertrichosis, leukotrichia and folliculitis are four major complications of intense pulsed light hair removal therapy. Journal of Dermatologic Treatment. 2008;19(6):360–363.

Radmanesh M. Paradoxical hypertrichosis and terminal hair change after intense pulsed light hair removal therapy. Journal of Dermatologic Treatment. 2009;20(1):52–54.

Raulin C, et al. Treatment of port-wine stains with a noncoherent pulsed light source: a retrospective study. Archives of Dermatology. 1999;135(6):679–683.

Raulin C, et al. [Excimer laser. Treatment of iatrogenic hypopigmentation following skin resurfacing]. Hautarzt. 2004;55(8):746–748.

Rheingold LM, Fater MC, Courtiss EH. Compartment syndrome of the upper extremity following cutaneous laser surgery. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 1997;99(5):1418–1420.

Sriprachya-anunt S, et al. Facial resurfacing in patients with Fitzpatrick skin type IV. Lasers in Surgery and Medicine. 2002;30(2):86–92.

Tanzi EL, Williams CM, Alster TS. Treatment of facial rhytides with a nonablative 1,450-nm diode laser: a controlled clinical and histologic study. Dermatologic Surgery. 2003;29(2):124–128.

Torezan LA, Osorio N, Neto CF. Development of multiple warts after skin resurfacing with CO2 laser. Dermatologic Surgery. 2000;26(1):70–72.

Trelles MA. Laser resurfacing today and the ‘cook book’ approach: a recipe for disaster? Journal of Cosmetic Dermatology. 2004;3(4):237–241.

Vlachos SP, Kontoes PP. Development of terminal hair following skin lesion treatments with an intense pulsed light source. Aesthetic Plastic Surgery. 2002;26(4):303–307.

Ward PD, Baker SR. Long-term results of carbon dioxide laser resurfacing of the face. Archives of Facial Plastic Surgery. 2008;10(4):238–243. discussion 244-245

Wareham WJ, et al. Adverse effects reported in pulsed dye laser treatment for port wine stains. Lasers in Medical Science. 2009;24(2):241–246.