16 Complications

Introduction

Each peeling agent carries with it a unique set of possible complications; however, there are some complications that can occur no matter which solution is used. Obviously, the more aggressive the agent employed the more potential for error and side effects. Likewise, more aggressive, deeper application techniques have increased risk. Prior to beginning a peel, all of the potential dangers of the procedure should be weighed against its potential benefits in order to maximize desired results and minimize problems. See Table 16.1 and also see Box 16.1.

Table 16.1 Sequelae versus adverse reactions and complications of chemical peels

| Minor sequlae | Adverse reactions | Complications |

|---|---|---|

| Pain Erythema Pruritus Swelling/edema Acne/milia Ecchymoses |

Hypo-/Hyperpigmentation Lines of demarcation Persistent erythema Infection Herpes reactivation |

Scarring Arrythmias (phenol) Toxicity (salicylic) Corneal damage |

Box 16.1

Key features

Complications Possible in All Types of Peel

• Swelling

Although swelling is more prominent in deeper peels, every peeling agent can cause swelling. This edema usually surfaces in 24 to 72 hours after the peel and is usually a fairly mild and expected sequelae of the procedure. In some cases, however, the edema may be severe enough to swell the eyes shut. This severe swelling may in some instances take several days to resolve. Nevertheless, this complication will be less worrisome to the patient if the possibility is raised before the procedure is done. Application of ice and proper wound care to the affected areas can serve to reduce the possibility of severe swelling. In severe cases systemic corticosteroids may be required to reduce swelling. Although some physicians routinely prescribe preoperative oral steroids for resurfacing procedures there is the possibility of impairing wound healing. It is more logical to reserve systemic steroids for the few patients who experience severe edema. See Box 16.2.

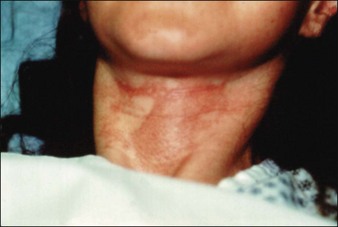

• Persistent erythema

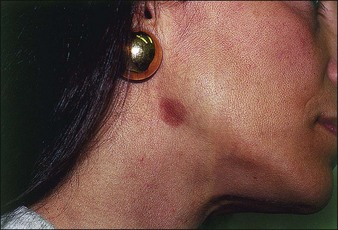

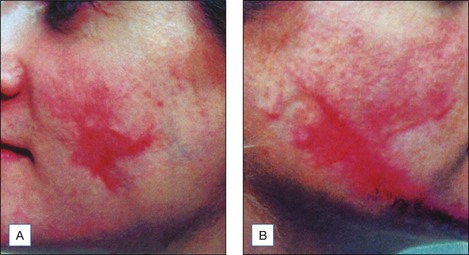

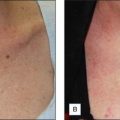

Erythema is common after all peel types. It is usually more noticeable and lasts longer in medium and deeper peels. Phenol peels usually are accompanied by erythema lasting 6 to 8 weeks before resolving. Erythema from TCA peels tends to fade in 2 to 3 weeks. Erythema is a natural response to the procedure; however, any erythema lasting longer than expected must be observed carefully for the possibility of scar formation (Figs 16.1–16.3). This ‘persistent’ erythema is best treated as soon as it is recognized with potent topical steroids. If there is no response, intralesional, oral or intramuscular steroids may be required. Resistant erythema often responds to pulsed dye lasers or intense pulsed light devices. See Boxes 16.3 and 16.4.

Figure 16.3 Same patient as in Fig. 16.2, several weeks later, beginning to develop early hypertrophic scar in area of previous erythema

• Ocular injuries

All acids are potentially dangerous to the eyes. Physicians must take great care when peeling around the orbital region. Inadvertent splashing of drops of acid can occur quite easily. Also retrograde wicking of acid through tears and in to the eyes is possible. Dermatologists are taught to maintain a dry cotton tipped applicator for immediate blotting of tears or acid solution near the lashes. If an acidic peeling solution does reach the eye, rapid, copious lavage with saline will dilute the acid and usually prevent corneal damage. Lavage should be performed immediately if the patient complains of burning in the eyes. Phenolic compounds spilled in to the eye respond better to washing out with large amounts of mineral oil (Box 16.5).

• Infection

Because the acids used as peeling agents are bacteriocidal, infection is less likely to develop after chemical peels compared to other skin procedures. However, occlusive ointments containing vegetable fats, petrolatum, and various moisturizers can promote the growth of pathogens such as species of Streptococcus, Staphylococcus and Pseudomonas (Fig. 16.4). The use of topical antibiotic ointments intranasally can help to decrease the risk of infection in susceptible individuals. To decrease the possibility of infection, patients should be instructed to remove excess crusted or necrotic skin using compresses of 0.5% acetic acid soaks (to 1 cup warm water, add 1 teaspoon white vinegar) three times a day and followed by gentle washing. However, as soon as the crusts disappear, the acetic acid should be discontinued, since it is an irritant and will slow down healing.

Postpeel infections can be very dangerous because they commonly lead to scarring. When they occur, early and aggressive treatment with broad-spectrum antibiotics is necessary. Bacterial cultures and gram stains can be helpful in determining the proper antibiotic to be used since differentiating between infections can be difficult in the background of healing skin. Candida infections can also occur in some patients and are difficult to diagnose since the epidermis is eroded (Fig. 16.5); however, a gram stain will show the organism. These should be treated appropriately with oral ketoconazole or fluconazole (Diflucan).

• Ecchymosis

Ecchymosis is a rare complication of chemical peeling that can occur in the infraorbital area of some patients (Fig. 16.6). It is usually only seen in those individuals who experience severe edema after the peel. Patients with significant actinic damage and cutaneous atrophy are also more likely to experience this problem. This complication is mostly a cosmetic one since it resolves spontaneously, but patients who are at risk should be informed of the possibility. Treating the swelling before the ecchymosis appears to be the best prevention.

• Hypopigmentation

Lighter pigmentation is a normal result of peeling. In patients with fairer complexions, treated skin usually reverts toward its original pre-sun-damaged state. Since peeling agents cause exfoliation, the amount of melanin dispersed in the epidermis will be decreased as these cells are sloughed off. This lightening is expected and transient in epidermal peels. If the entire epidermis through the basal layer is removed, the melanocytes responsible for pigment will also be removed. Thus with dermal peels, temporary hypopigmentation is expected since new melanocytes will need time to migrate into the new epidermis. Permanent hypopigmentation, however, is a complication of peeling (Fig. 16.7). It occurs more commonly in darker skinned individuals. Usually this appears in a haphazard distribution, which is often due to uneven penetration of peeling agents and can be quite noticeable. Infection and/or scarring can also lead to hypopigmentation. Hypopigmentation can be particularly severe in those individuals who have type III or darker skin. Phenol peels can produce a unique form of hypopigmentation that results in a porcelain appearance to the skin that is not noticeable until the erythema has faded. This has been referred to as the ‘alabaster statue’ look, and appears to be due to a direct melanotoxic effect of phenol.

• Hyperpigmentation

Pigmentary changes can occur with any depth of peeling (Fig. 16.8). However, patients with lighter skin tones (Fitzpatrick type I–II) are less likely to develop hyperpigmentation. Individuals with types III to VI skin can undergo peels, but they must be made aware of their greater risk of hyperpigmentation as well as color differences in peeled vs non-peeled skin (Fig 16.9). Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation is more likely if the patient has experienced this before from other skin injuries. A test area may be done in those individuals who are wary of these types of changes (Fig. 16.10); however, it must be mentioned that hyperpigmentation may still occur in spite of a negative test site.

If hyperpigmentation occurs hydroquinone 4% or higher is the mainstay of treatment. Once the skin is sufficiently healed, tretinoin can be added to increase the bleaching effect. Commercial or compounded formulations that include these agents and a topical steroid are also useful. Patients should be advised to use sunscreens and avoid unnecessary sun exposure to the peeled areas as this can prevent further pigment changes and lessen the duration of the darker areas. Also, patients using birth control pills, estrogens, or other photosensitizing agents are at greater risk for this complication. Patients should be encouraged to avoid these if possible. Likewise, patients who would become pregnant within 6 months of the peel have higher risk of hyperpigmentation, even if strict sun avoidance is maintained. Those with darker skin types may require treatment to prevent or diminish post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation for up to 1 year postoperatively. Patients with preexisting hyperpigmentation may best be treated with superficial peels every 2 to 4 weeks in order to avoid the increased potential for post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation from deeper peels (Box 16.6).

Box 16.6

Postpeel hyperpigmentation

Who is affected? Darker (types III–VI) skin usually.

Tip: Test spot peels prior to performing full-face procedures in at-risk individuals.

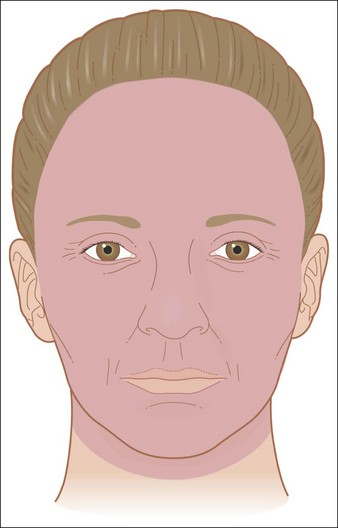

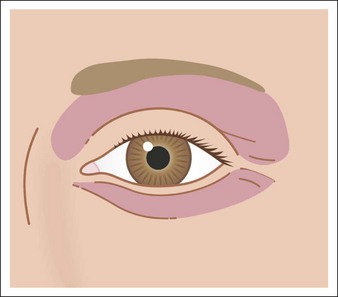

• Demarcation lines

After a chemical peel, an obvious line of pigmentary change may form where the peeled skin meets unpeeled skin. The most common areas for demarcation lines to occur are below the mandible, near the eyes, and periorally. To avoid this complication peels must be carried out beyond the desired area by about 5 mm and should be feathered (by using lower acid concentrations or less aggressive peeling application) into the surrounding skin to create a normal fade. On the mandible, the peel should be carried out below the angle of the jaw and onto the neck (Fig. 16.11). However, patients who later undergo a facelift procedure may have this line raised up to the face. To create an even appearance around the eyes, peels should be applied right up to the lashes on the lower lids and to the supratarsal crease on the upper lids (Fig. 16.12). When peels are done on the perioral area only, the peel must continue into the nasolabial folds, but not onto the cheeks (Fig. 16.13). Another problematic area is the hairline. In those with receding hairline the peel should be continued onto the scalp. Repeeling of the affected areas is the best remedy for demarcation lines.

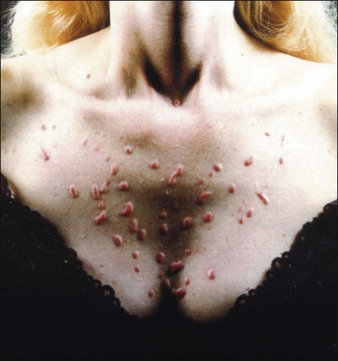

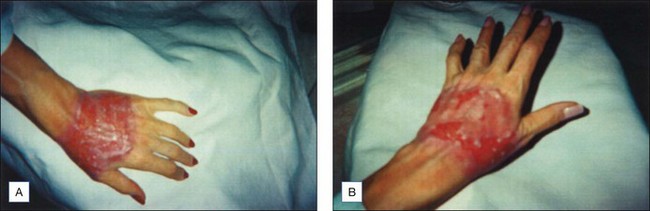

• Scarring

Although uncommon in chemical peeling, scarring is the most difficult complication for both physicians and patients to deal with (Figs 16.14 and 16.15). Physicians should always warn patients beforehand of this possibility and should be aware of patients who are more at risk of developing scarring. Any patient with a history of poor wound healing, keloid formation or excessive actinic damage, as well as patients who are undergoing deep peeling into the reticular dermis, are more likely to have some degree of scarring. Nonfacial skin such as the neck, dorsal hands, and chest do not have sufficient follicular structures to undergo deep peeling without risk of scarring (Fig 16.16 and 16.17). Furthermore, physicians should be careful not to repeel areas that have not had adequate time to heal from a prior peel or other injury. Isotretinoin has also been associated with increased incidence of scarring, owing to disruption of collagenase production; thus, patients who have been on this treatment should wait at least 6 months before having a medium to deep chemical peel (Box 16.7).

Figure 16.14 Hypopigmentation, scarring, and persistent erythema 6 months following an aggressive 35% TCA peel

Some early signs that scarring may be occurring are persistent erythema and pruritus. If these should occur, the patient should be treated immediately with a high potency topical steroid. This approach must be weighed against the risks of prolonged steroid use such as atrophy and telangiectasias. Delayed healing is another warning sign of incipient scars (Fig. 16.17). If peeled skin fails to reepithelialize as expected, aggressive intervention with biologic dressings and antibiotic coverage may remedy this problem. Generally wounds that have not reepithelialized within 2 weeks have a good chance of scarring. If scars occur, they are best treated initially with an intralesional injection of steroids. Massage and compression over time can also sometimes be helpful in softening scars. Steroid impregnated tape can soften firm scars. Pulsed dye lasers and intense pulsed light devices are helpful in improving red scars. See Box 16.8.

Beeson WM, Rachel JD. Valcyclovir prophylaxis for herpes simplex virus infection or infection resuming following laser resurfacing. Dermatololgic Surgery. 2002;28:431-436.

Brodland DG, Cullimore KC, Roenigk RK, et al. Depths of chemexfoliation induced by various concentrations and application techniques of trichloroacetic acid in a porcine model. Journal of Dermatologic Surgery and Oncology. 1989;15:967-971.

Brody HJ. Chemical peeling. Mosby-Yearbook: St. Louis; 1992.

Brody HJ, Hailey CW. Medium-depth chemical peeling of the skin: a variation of superficial chemosurgery. Journal of Dermatologic Surgery and Oncology. 1986;12:1268-1275.

Coleman WPIII, Futrell JM. The glycolic acid trichloroacetic acid peel. Journal of Dermatologic Surgery and Oncology. 1994;20:76-80.

Fung JF, Sengelmann RD, Kenneally CZ. Chemical injury to the eye from trichloroacetic acid. Dermatologic Surgery. 2002;28:609-610.

Heria O, Nemeth AJ, Taylor JR. Tretinoin accelerates healing after trichloroacetic acid chemical peel. Archives of Dermatology. 1991;127:678-682.

Landau M. Cardiac complications in deep chemical peels. Dermatologic Surgery. 2007;33:190-193.

Matarasso SL, Salman SM, Glougau RC, et al. The role of chemical peeling in the treatment of photo damaged skin. Journal of Dermatologic Surgery and Oncology. 1990;16:945-954.

Monheit GD. The Jessner’s + TCA peel: a medium depth chemical peel. Journal of Dermatologic Surgery and Oncology. 1989;15:945-950.

Morrow DM. Chemical peeling of the eyelids and periorbital area. Journal of Dermatologic Surgery and Oncology. 1992;18:102-110.

Spinowitz AL, Rumsfield J. Stability–time profile of trichloroacetic acid at various concentrations and storage conditions. Journal of Dermatologic Surgery and Oncology. 1989;15:874-875.

Spira M, Gerow FJ, Hardy SB. Complications of chemical face peeling. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 1974;54:397.

Stegman SJ. A comparative histologic study of the effects of three peeling agents and dermabrasion on normal and sun damaged skin. Esthetic Plastic Surgery. 1982;6:123.

Zakopoulou N, Kontochristopoulos G. Superficial chemical peels. Journal of Cosmetic Dermatology. 2006;5:246-253.