Complementary Therapies as Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Physical Therapy Interventions

What Are Complementary Therapies?

The goal of most of these therapies is to “unblock” obstructed body energy so that the body can heal itself.1 It is hypothesized that homeostasis, balance, and self-regulation (the highly advanced ability of the body/mind to supply optimum conditions for metabolism, such as proper pH, body temperature, etc.) result from the unrestricted flow of body energy, along with molecules from breathing, fluid, and nutrition.2,3 A system out of balance becomes vulnerable to early mortality. A system in balance becomes resistant to inflammation. Some suggest that inflammation is the foundation of all diseases and disorders.4 Two large studies, one in men and one in women, demonstrated that higher levels of C-reactive protein correlate with a higher risk for heart attack and stroke and treatments that reduce C-reactive protein level reduce heart disease risk.5,6 Therefore complementary therapies are used to facilitate the flow of body energy (or chi) and thus help the body restore balance and return to a healthier state.

Examples of Complementary and Alternative Therapies

The following are examples of complementary and alternative therapies that have been found to be useful in health care. A list and brief description of these therapies can be found in Appendix E.

Manual Therapies

Manual therapies, also known as body work, include myofascial release, craniosacral therapy, Rosen method, Rolfing, Hellerwork, soma, neuromuscular therapy, massage, and osteopathic and chiropractic medicine. The manual therapies involve the use of hands on the body/mind surface to stimulate bioelectromagnetic force. How this occurs remains a mystery. Research by Hunt and others is currently being conducted to measure energy flow from the body.7–9 Perhaps both mechanical and energetic forces stimulate response from the tissue in several ways. It has been hypothesized that mechanical force may be transformed into a chemical response within the collagen of the myofascia, causing a flow of the polyglycoid layer of the collagen by way of a piezoelectric effect.10 For patients with cardiovascular and pulmonary pathology, the manual therapies can assist in opening up the ribcage and vertebral spine to allow increased ventilation and better posture, thereby supporting cardiorespiratory health.

Mind/Body Interventions

Mind/body intervention include psychotherapies, support groups, meditation, imagery, hypnosis, dance and music therapy, art therapy, prayer, neurolinguistic psychology, biofeedback, yoga, Pilates, and tai chi. These interventions are examples of how movement and verbal and nonverbal communication with the mind/body can open up new pathways for thought and thereby unblock potentially blocked energy flow or chi. Likewise, with the new understandings of epigenetics (see discussion below), the energy (or vibration) of one’s perception or belief drives DNA function, either for means of growth or for means of protection/survival.2,3 These interventions are quite prevalent in the treatment of cardiorespiratory and pulmonary disorders. Stress is positively affected when the person is aware of thoughts and habits that affect the mind/body in a negative way. These interventions put the patient back in control of negative behaviors, and focusing on the breath is often an integral part of furthering relaxation.

Energy Work

Bioelectromagnetics

Bioelectromagnetics include thermal applications of magnets and nonionizing radiation such as radiofrequency hyperthermia laser and pulsed electromagnetic field therapy. Credible research exists on the effects of electromagnetic energy for wound healing and bone repair. Biomicroelectromagnetics is the term applied to the energy that seems to emanate from the hands of people who have been accepted as healers.8 Ultrasound and diathermy have been used in physical therapy for decades as deep heat mechanisms, and although there is not a clear understanding of the mechanism of action, it undoubtedly involves a stimulation of energy flow; therefore this therapeutic approach falls in the bioelectromagnetic category. The use of magnets in physical therapy is quite controversial, but there are some very compelling results from case studies that make it important to include in this category.

Herbal Approaches

Naturopathy and homeopathy represent the use of plants and animal substances to fight off disease and the use of wise nutrition to combat illness. Naturopathy, like osteopathic medicine, represents an entire system of health care that uses homeopathy, osteopathy, proper nutrition, and other means to bring about healing. Naturopathic physicians complete 4 years of medical school. Homeopathy involves the use of minute chemicals in diluted solution to resolve chemical imbalances in the body. Proper nutrition has long been associated with cardiac and pulmonary health, especially in Dean Ornish’s plan for healing from cardiac pathology.11

Mind/Body Link

Mind/body health care has brought about a way of linking the traditional linear research methods with the more contemporary, complementary, and alternative health care practices. The influence of the mind on the body was first introduced in the Western hemisphere by Herbert Benson, a well-known Harvard cardiologist, through his research on Tibetan monks who were able to control their autonomic nervous system to the extent that they could lower their body temperatures and respiration rates and enter a wakeful, hypometabolic physiological state by will.12 This information shocked the Western world, and Benson presented his data most dramatically by videotaping the actual sessions of the monks taking control of their bodies with their minds.

The proof that the mind and body are inextricably linked has since been well documented in various studies. Indeed, there is a basic science devoted to the study of the effect of the mind on the body: psychoneuroimmunology, a term that Ader and Cohen are credited with creating. Studies have shown that the mind affects the immune system by way of the autonomic nervous system and by way of the “fluid” nervous system, or the nonadrenergic and noncholinergic nervous system.13

Candice Pert has clearly articulated the physiological functioning of the fluid nervous system, which manifests by way of the effects of thought on the neurotransmitters, the neuropeptides, and the steroids of the body.14 The neurotransmitters and the neuropeptides communicate with most of the cells of the body. This science has been termed psychoneuroendocrinology. It is no longer correct to assume that the mind resides only in the cranium or the brain. In truth, the mind has been shown to reside in every cell in the body. According to Pert and others, the science clearly reveals that all cells have memory.14 The biochemistry of psychoneuroendocrinology reflects a flow that is different from that of microelectro-potentials or the exchange of energy from the hands of the therapist, but which illustrates, nonetheless, that the mind and the body are inseparable and the mind communicates with every cell of the body.

Complementary and alternative therapies are energy-based therapies that require an understanding that there is such a phenomenon as vital flow of energy in the body and that the natural state of the body is to be healthy.15 Cells are constantly in a state of flux, with old cells dying off and new cells being created continuously. But the body/mind persists in continuously working toward fighting off disease and healing cells whose loss would threaten the thriving of the entire system. With this awareness, illness is understood as an aberration set up by an imbalance caused by restriction in flows. The body has many energies, or vibrations, and the ways that we can observe energy at work in the body are varied. For example, electrocardiograms, electroencephalograms, and electromyograms all measure the energy output from various body organs. The piezoelectric effect, another energy phenomenon, enables osteoblastic activity, which keeps our bones strong. Mechanical energy in gravity is transformed to chemical energy to allow the osteoblasts to deposit calcium appropriately in our skeleton. But now we understand that perhaps the most powerful of the many vibrations our cellular receptors respond to is the vibration of perception.

The science of epigenetics posits that the genes in our cells respond to vibrational signals. For the cells to function, receptors on the surface of the cell wall must respond to the vibration to which they are attuned, resulting in a cascade of actions that lead to the DNA ordering the appropriate protein chain linkage to result in the needed function.2,14 Basic to the understanding of the mind and body being inseparably linked is the fact that one of the most powerful vibrations that cells respond to is the vibration of perception or belief.2,14 The more a person perceives threat, stress, or danger, the more there is a resulting vibration to which cells respond with an autonomic fight or flight response—the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis.16 It has been long understood that chronic stress contributes to pathology in the cardiovascular and pulmonary systems. The DNA of cells is responding in a “digital” (on-or-off) way either to signals vibrating for growth needs or signals vibrating for protection needs. When protection needs take over, blood is shunted to life-sustaining viscera and to the extremities for flight or fight. Thus some organs are not being nourished in a health-producing manner. Over time, immune system function is also diminished and this can lead to inflammation and disease of the heart and lungs.17 A system out of balance becomes vulnerable to early mortality. A system in balance becomes resistant to inflammation. As stated previously, some suggest that inflammation is the foundation of all diseases and disorders.4

Biomicroelectro-potentials, or the subtle energies in electromagnetic fields that emanate from the hands of “healers,” are currently being researched.8,18 It is believed that complementary and alternative therapies have an effect on patients by way of the energy that emanates from the healer’s hands. This energy is of a frequency of 0.3 to 30 Hz, which is usually centered around 8 to 10 Hz.19,20

Most current diseases, especially the chronic diseases that affect people, do not lend themselves to single-purpose cures. Chronic illness is most adequately addressed when the patient is involved in the healing process as an active partner, when the patient is willing to make certain lifestyle changes to eliminate choices that interfere with wellness, and when illness is perceived by patients and practitioners not as a simple biophysiological event but as a system or contextual event. We are all consciously and unconsciously influenced by a variety of systems that we are embedded within and that mandate our reactions to inflammation and illness. No two people react to illness in the exact same way, and no two people heal from illness in the exact same way. Practically any physical therapist or health care professional will admit that how a person thinks or perceives has an enormous amount to do with how he or she responds to health and illness. A vast range of systems affect all of us at any given time—just a few examples are our birth order, our identity, how we feel about ourselves and our family members, how well we enjoy our work and our recreation, how meaningful our relationships are, what the weather is like, who won the Super Bowl, and what we ate for breakfast.21

Traditional Therapies Applied from a Holistic Approach—Intention

Researchers confirm the importance of hope and faith in one’s physician and practitioners, including physical therapists.22 It has been established that a patient’s belief that the practitioner has hope for the patient’s recovery seems to help, but exactly how this facilitates healing remains unclear. It seems to be related to the concept of intention and the effects of consciousness and nonlocal mind.22

To ignore the positive effect of therapeutic presence is to neglect a powerful intervention. How practitioners interact with their patients, not just what they do, is vitally important.1 Time and again, patients mention that a critical factor in their healing response was the positive effect of being truly listened to by their care provider. Now research is finally documenting the effects of positive intention and the therapeutic exchange of energy.22

The Problem of Scientific Evidence

Complementary therapies such as tai chi, acupuncture, biofeedback, meditation, cognitive behavioral therapy, music therapy, hypnosis, electrical stimulation, prayer and distant healing efforts, yoga, and qi gong have been shown to be effective in the relief of pain and anxiety and in the improvement of balance by way of the randomized controlled trial (RCT).23 Literature reviews of mind/body therapies in the treatment of musculoskeletal disorders with implications for older adults have been conducted.24,25 Still, the fact remains that many complementary therapies, especially those manual therapies designed to assist in the release of fascial restrictions in order to restore the flow of the body’s self-regulating energy, do not lend themselves to study by the RCT because energy itself cannot be measured or seen. Only the results of energy can be measured (heat, work, movement, etc.), and we cannot yet validate what results occur from what intervention, except by way of anecdote and measuring the effects of treatment on impairments and function. However, scientists such as Valerie Hunt, James Oschman, Gary Schwartz, Linda Russek, Candace Pert, and others are busy working out the biochemical, quantum physics, and systems theories that postulate physiological and biochemical mechanisms of action, which will allow us to hypothesize basic cellular energy theory.10,26–28 This basic cellular energetic theory can then be tested to describe the evidence that we need. If we can hypothesize a basic mechanism of action of myofascial release, for example, then we can examine whether that action does indeed take place in the way that the theory postulates. However, we will never be able to see energy, any more, for instance, than we can see velocity.

Demonstration of efficacy and safety is paramount to professional care. But is this goal actually achievable to the satisfaction of the scientific community? Not as long as reductionism remains the gold standard in the search for reality. In 1997, the Council on Scientific Affairs of the American Medical Association suggested that “physicians should evaluate the scientific perspectives of unconventional theories for treatment and practice, looking particularly at potential utility, safety and efficacy of these [holistic] modalities.”23

Use of Specific Complementary Therapy Interventions in Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Conditions

As described throughout Part III of this book, the goal of physical therapy intervention is to improve the efficiency of the oxygen transport and gas exchange systems. The decision to use a specific complementary therapy and integrate it into more traditional cardiovascular and pulmonary treatments is often dependent on the practitioner’s familiarity with the intervention. Rehabilitation practitioners without specialized training in a complementary therapeutic intervention frequently do not realize that they are already incorporating components of complementary therapies in established, traditional therapeutic interventions. Patient education, including behavioral and biofeedback techniques used to alter breathing patterns and reduce sympathetic nervous system stimulation, are forms of mind/body therapies. These interventions have been studied extensively, reported in the literature, and are widely used and accepted in clinical practice.29–31

Physical therapy practitioners with expertise in a specific complementary intervention may decide to focus their treatment on cardiovascular and pulmonary impairments. Tai chi and yoga are mind/body therapies that emphasize coordinated breathing with movement. These interventions may be used as the primary approach to treat the impairment, or they may complement traditional physical therapy. The body of evidence addressing the usefulness of these interventions in improving oxygen transport has expanded in both quantity and quality in recent years.32–36

Other interventions that have not been subjected to rigorous, scientific study may still be worthy of clinical application. For example, the Alexander technique, which emphasizes posture and movement, intuitively suggests an improvement in oxygen transport. An improvement in posture optimizes muscle function, thoracic cage efficiency, and hence oxygen transport; however, there is limited research published on this technique in relation to the cardiovascular and pulmonary systems.37

The increasing consumer demand for complementary and alternative medical (CAM) therapies has occurred despite the lack of rigorous or acceptable scientific investigation into many of them. In an attempt to protect the general public from unethical and unsafe practices, the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM) have proposed that large-scale clinical trials be performed to determine standards of practice and safety standards.38 NCCAM proposed initiatives to support research and the development of specialized centers to study cardiovascular disease and also reported a 96% increase in funding for these initiatives in 2005.39,40 It is important for all health care practitioners to become familiar with some of the more popular CAM therapies, recognize that our patients are using them, and be especially aware of the effects of these therapies on the cardiovascular and pulmonary systems.

Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Responses to Complementary and Alternative Medical Therapies

Tai Chi

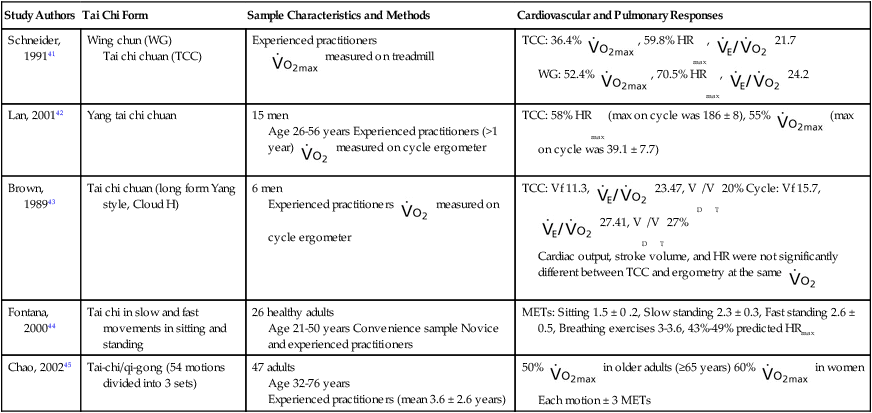

Tai chi is one of the most well-studied mind/body therapies. During sessions of the many forms of tai chi (see Appendix E), cardiovascular responses have been documented in novices as well as in master practitioners. In several of these studies, responses have been compared to cardiovascular and pulmonary responses observed in other forms of exercise (e.g. bicycle ergometry and treadmill ambulation). Most investigations are small and have methodological shortcomings. A brief sampling of the results of several studies addressing the cardiovascular and pulmonary responses found during tai chi practice can be found in Table 27-1. In general, in these studies of healthy individuals, gender and experience level do not seem to influence the responses. It is reasonable to conclude that tai chi is a low- to moderate-intensity exercise that emphasizes the oxygen transport system. Investigators generally conclude that tai chi is a safe activity for healthy individuals. Prescreening for mind/body interventions is recommended, however, just as would be expected for any other exercise intervention.37

Table 27-1

Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Responses Found During Continuous Tai Chi Exercise

| Study Authors | Tai Chi Form | Sample Characteristics and Methods | Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Responses |

| Schneider, 199141 | Wing chun (WG) Tai chi chuan (TCC) |

Experienced practitioners measured on treadmill measured on treadmill |

TCC: 36.4%  , 59.8% HRmax, , 59.8% HRmax,  21.7 21.7WG: 52.4%  , 70.5% HRmax, , 70.5% HRmax,  24.2 24.2 |

| Lan, 200142 | Yang tai chi chuan | 15 men Age 26-56 years Experienced practitioners (>1 year)  measured on cycle ergometer measured on cycle ergometer |

TCC: 58% HRmax (max on cycle was 186 ± 8), 55%  (max on cycle was 39.1 ± 7.7) (max on cycle was 39.1 ± 7.7) |

| Brown, 198943 | Tai chi chuan (long form Yang style, Cloud H) | 6 men Experienced practitioners  measured on cycle ergometer measured on cycle ergometer |

TCC: Vf 11.3,  23.47, VD/VT 20% Cycle: Vf 15.7, 23.47, VD/VT 20% Cycle: Vf 15.7,  27.41, VD/VT 27% 27.41, VD/VT 27%Cardiac output, stroke volume, and HR were not significantly different between TCC and ergometry at the same  |

| Fontana, 200044 | Tai chi in slow and fast movements in sitting and standing | 26 healthy adults Age 21-50 years Convenience sample Novice and experienced practitioners |

METs: Sitting 1.5 ± 0 .2, Slow standing 2.3 ± 0.3, Fast standing 2.6 ± 0.5, Breathing exercises 3-3.6, 43%-49% predicted HRmax |

| Chao, 200245 | Tai-chi/qi-gong (54 motions divided into 3 sets) | 47 adults Age 32-76 years Experienced practitioners (mean 3.6 ± 2.6 years) |

50%  in older adults (≥65 years) 60% in older adults (≥65 years) 60%  in women in womenEach motion ± 3 METs |

Several authors have investigated the cardiovascular and pulmonary benefits of a prolonged program of tai chi. In contrast to the studies reported in Table 27-1, several others demonstrate that experienced tai chi chuan practitioners achieve significantly higher maximum oxygen consumption ( ) levels than do sedentary subjects.46–52 These authors conclude that tai chi is a form of aerobic exercise, it has benefits for health-related fitness, and it may slow the decline in cardiorespiratory fitness in older, healthy individuals.

) levels than do sedentary subjects.46–52 These authors conclude that tai chi is a form of aerobic exercise, it has benefits for health-related fitness, and it may slow the decline in cardiorespiratory fitness in older, healthy individuals.

In a small study (n = 32), Wang and colleagues (2002)34 studied endothelium-dependent dilation in skin vasculature in healthy, older (69.9 ± 1.5 years), male tai chi practitioners and a control group. Their results demonstrate that when compared with older sedentary men (67.0 ± 1.0 years), long-time, experienced practitioners of tai chi have more favorable arterial and venous hemodynamics. In some cases these vascular findings were comparable to a group of younger, healthy, sedentary men (23.5 ± 0.68 years).

Young and colleagues (1999)53 compared the effects of aerobic exercise and tai chi on blood pressure responses in older individuals (79% women). In this RCT of 62 sedentary older adults (66.7 ± 5.2 years), subjects participated in 12 weeks of either aerobic exercise or tai chi. Baseline systolic blood pressure (BP) was 130 to 159 mm Hg. Subjects were not on antihypertensive medication, and results indicated similar statistically significant reductions in systolic BP occurred in both intervention groups. Of note, the aerobic exercise group demonstrated a significant increase in predicted  , whereas the tai chi group did not. The authors concluded that both light- and moderate-intensity exercise programs can have an important effect on systolic blood pressure. Thornton and colleagues (2004)54 found similar reductions in BP in normotensive sedentary women, ages 33 to 55 years. In contrast, Chen and colleagues (2006)55 found no reduction in BP in older adult residents of long-term care facilities when they participated in a 6-month simplified tai chi program. Their program was customized for deconditioned subjects, and the authors concluded that the lack of significant changes in BP was due to the very low intensity of the exercise.

, whereas the tai chi group did not. The authors concluded that both light- and moderate-intensity exercise programs can have an important effect on systolic blood pressure. Thornton and colleagues (2004)54 found similar reductions in BP in normotensive sedentary women, ages 33 to 55 years. In contrast, Chen and colleagues (2006)55 found no reduction in BP in older adult residents of long-term care facilities when they participated in a 6-month simplified tai chi program. Their program was customized for deconditioned subjects, and the authors concluded that the lack of significant changes in BP was due to the very low intensity of the exercise.

Yoga

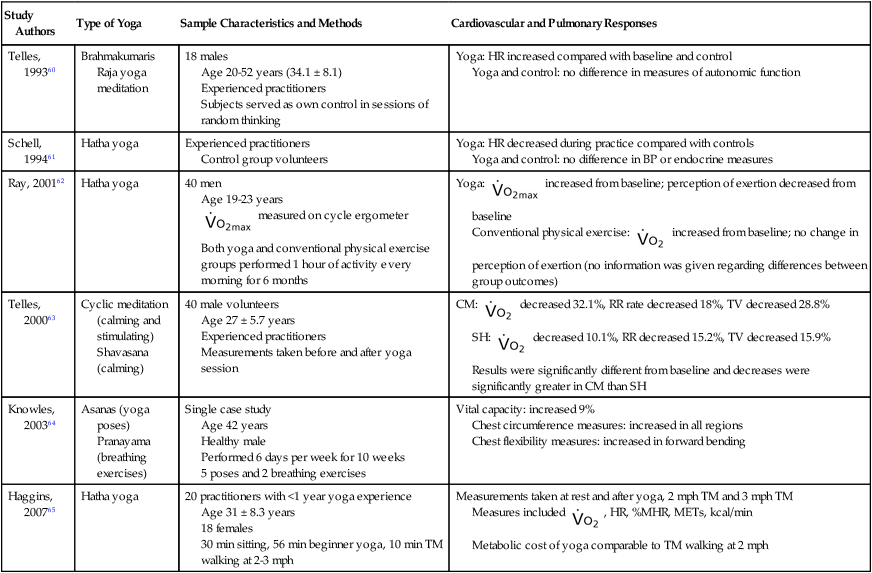

Another popular mind/body intervention is yoga. The cardiovascular responses to several types of yoga in healthy children and adults have been investigated.56–59 General conclusions are difficult to make, given the weaknesses of the studies and the different characteristics of the types of yoga studied. Table 27-2 lists cardiovascular and pulmonary responses before and after a single yoga session or a period of yoga practice. Overall it appears that those forms of yoga that primarily involve meditation show minimal changes in cardiovascular and pulmonary parameters when compared with those forms that include stimulation phases.

Table 27-2

Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Responses to Yoga Practices in Healthy Individuals

| Study Authors | Type of Yoga | Sample Characteristics and Methods | Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Responses |

| Telles, 199360 | Brahmakumaris Raja yoga meditation | 18 males Age 20-52 years (34.1 ± 8.1) Experienced practitioners Subjects served as own control in sessions of random thinking |

Yoga: HR increased compared with baseline and control Yoga and control: no difference in measures of autonomic function |

| Schell, 199461 | Hatha yoga | Experienced practitioners Control group volunteers |

Yoga: HR decreased during practice compared with controls Yoga and control: no difference in BP or endocrine measures |

| Ray, 200162 | Hatha yoga | 40 men Age 19-23 years  measured on cycle ergometer measured on cycle ergometerBoth yoga and conventional physical exercise groups performed 1 hour of activity every morning for 6 months |

Yoga:  increased from baseline; perception of exertion decreased from baseline increased from baseline; perception of exertion decreased from baselineConventional physical exercise:  increased from baseline; no change in perception of exertion (no information was given regarding differences between group outcomes) increased from baseline; no change in perception of exertion (no information was given regarding differences between group outcomes) |

| Telles, 200063 | Cyclic meditation (calming and stimulating) Shavasana (calming) |

40 male volunteers Age 27 ± 5.7 years Experienced practitioners Measurements taken before and after yoga session |

CM:  decreased 32.1%, RR rate decreased 18%, TV decreased 28.8% decreased 32.1%, RR rate decreased 18%, TV decreased 28.8%SH:  decreased 10.1%, RR decreased 15.2%, TV decreased 15.9% decreased 10.1%, RR decreased 15.2%, TV decreased 15.9%Results were significantly different from baseline and decreases were significantly greater in CM than SH |

| Knowles, 200364 | Asanas (yoga poses) Pranayama (breathing exercises) |

Single case study Age 42 years Healthy male Performed 6 days per week for 10 weeks 5 poses and 2 breathing exercises |

Vital capacity: increased 9% Chest circumference measures: increased in all regions Chest flexibility measures: increased in forward bending |

| Haggins, 200765 | Hatha yoga | 20 practitioners with <1 year yoga experience Age 31 ± 8.3 years 18 females 30 min sitting, 56 min beginner yoga, 10 min TM walking at 2-3 mph |

Measurements taken at rest and after yoga, 2 mph TM and 3 mph TM Measures included  , HR, %MHR, METs, kcal/min , HR, %MHR, METs, kcal/minMetabolic cost of yoga comparable to TM walking at 2 mph |

Other Mind/Body Therapies

Although social support is not typically considered a mind/body therapy, part of the success of many of the CAM interventions has been attributed to group interactions or those interactions between subject and practitioner. In a review of 81 studies, Uchino and colleagues (1996)66 investigated the benefits of social support on the cardiovascular, endocrine, and immune systems. Social support includes individual, family, or group interactions. There is strong evidence correlating a decrease in cardiovascular reactivity in healthy individuals when social support is increased.

Manual Therapies/Body Work Therapies

There is a paucity of literature addressing cardiovascular and pulmonary responses to body work interventions in healthy individuals. One study of therapeutic massage demonstrated statistically significant reductions in cardiovascular parameters after a 3-day intervention of slow-stroke back massage on individuals in a rehabilitation setting.67 Twenty-four adults (age range 52 to 88 years) underwent daily intervention. Statistically significant decreases in systolic and diastolic BP were noted each day; this was true for heart rate (HR) and respiratory rate (RR) only on days 1 and 3. Subjects also reported improved perception and less anxiety.

Cottingham and colleagues (1988b)68 investigated the effects of the Rolf method of soft tissue mobilization on parasympathetic nervous system (PNS) tone in 32 young, healthy men. This RCT compared a group that performed 45 minutes of Rolfing with pelvic mobilization (pelvic lift) with a control group that received a 45-minute durational touch without Rolfing (pelvic lift intervention). At baseline all subjects had an anterior pelvic tilt. PNS tone was measured before, immediately after, and 24 hours after intervention. Results demonstrated a significant increase in PNS tone and decreased standing pelvic tilt angle in the intervention group. Earlier, Cottingham and colleagues (1988a)69 demonstrated an increase in PNS tone with the pelvic lift technique unrelated to the durational touch used simultaneously in the technique. The authors concluded that this intervention of soft tissue pelvic manipulation (i.e., durational touch plus pelvic lift) can help individuals with muscle dysfunction and conditions associated with reduced PNS activity and increased sympathetic nervous system activity. Reduced PNS and increased SNS can be representative of deconditioning.

In a small study of 12 children and adults, investigators attempted to examine the reliability of craniosacral intervention interpretation among three expert practitioners of craniosacral therapy.70 They also investigated the relationship of the craniosacral rate to HR and BP of subject and practitioner. Results demonstrated no interrater reliability among the three practitioners. Results also demonstrated no relationship between HR and BP and the craniosacral rates. Although this study did not attempt to report on the effects of craniosacral therapy on cardiovascular parameters, the results do shed light on potential considerations for future study design.

Green and colleagues (2004)71 conducted a rigorous review of the evidence for using craniosacral therapy. Nine of the 34 studies reviewed looked at whether movement of cranial bones was possible, and 10 of the 34 studies looked at whether cerebrospinal fluid moves rhythmically. The authors concluded that evidence supports the belief that there is a cranial “pulse” or rhythm that is separate from the cardiac or respiratory rhythms.

Energy Work Interventions

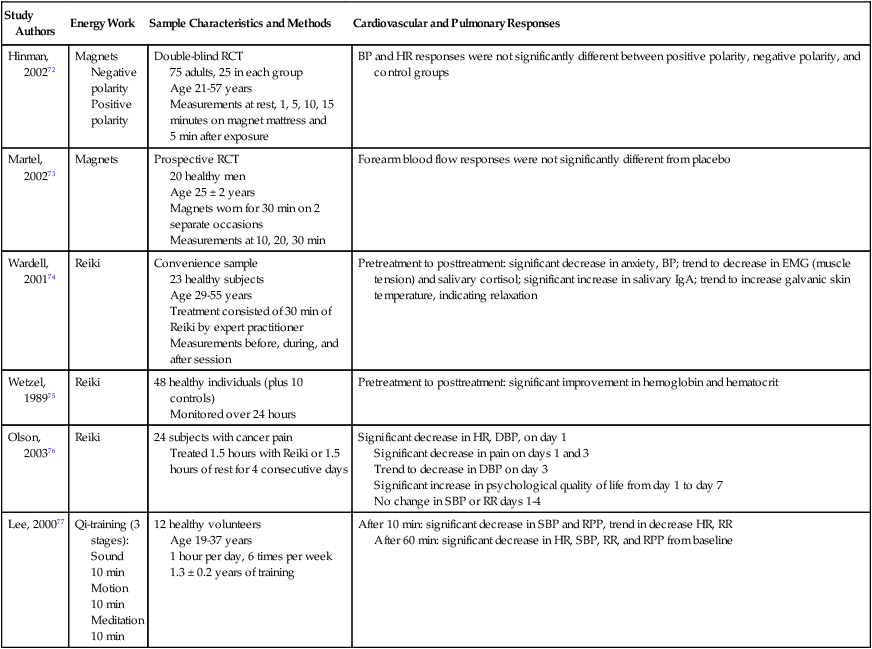

A few studies addressing the cardiovascular and pulmonary responses to energy work in healthy subjects have been conducted. Some of these are summarized in Table 27-3. In most cases, methodological weaknesses limit generalizations about the results. Studies of Reiki demonstrate trends toward increased relaxation and improved immune system markers.74–76 In a study of qi-training, the authors provide a detailed description of the intervention facilitating replication of the study with a larger sample.77 The two studies investigating responses to magnets demonstrate no significant differences from control.72,73 Of interest, in a study investigating the safety of prosthetic mini-magnets in individuals with cardiac pacemakers, the authors found no electrocardiographic changes in 9 of 12 subjects. When the magnets were moved at least 1 cm away from the pacemaker implant, the changes in the other 3 subjects no longer existed.78

Table 27-3

Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Responses to Energy Work in Healthy Individuals

| Study Authors | Energy Work | Sample Characteristics and Methods | Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Responses |

| Hinman, 200272 | Magnets Negative polarity Positive polarity |

Double-blind RCT 75 adults, 25 in each group Age 21-57 years Measurements at rest, 1, 5, 10, 15 minutes on magnet mattress and 5 min after exposure |

BP and HR responses were not significantly different between positive polarity, negative polarity, and control groups |

| Martel, 200273 | Magnets | Prospective RCT 20 healthy men Age 25 ± 2 years Magnets worn for 30 min on 2 separate occasions Measurements at 10, 20, 30 min |

Forearm blood flow responses were not significantly different from placebo |

| Wardell, 200174 | Reiki | Convenience sample 23 healthy subjects Age 29-55 years Treatment consisted of 30 min of Reiki by expert practitioner Measurements before, during, and after session |

Pretreatment to posttreatment: significant decrease in anxiety, BP; trend to decrease in EMG (muscle tension) and salivary cortisol; significant increase in salivary IgA; trend to increase galvanic skin temperature, indicating relaxation |

| Wetzel, 198975 | Reiki | 48 healthy individuals (plus 10 controls) Monitored over 24 hours |

Pretreatment to posttreatment: significant improvement in hemoglobin and hematocrit |

| Olson, 200376 | Reiki | 24 subjects with cancer pain Treated 1.5 hours with Reiki or 1.5 hours of rest for 4 consecutive days |

Significant decrease in HR, DBP, on day 1 Significant decrease in pain on days 1 and 3 Trend to decrease in DBP on day 3 Significant increase in psychological quality of life from day 1 to day 7 No change in SBP or RR days 1-4 |

| Lee, 200077 | Qi-training (3 stages): Sound 10 min Motion 10 min Meditation 10 min |

12 healthy volunteers Age 19-37 years 1 hour per day, 6 times per week 1.3 ± 0.2 years of training |

After 10 min: significant decrease in SBP and RPP, trend in decrease HR, RR After 60 min: significant decrease in HR, SBP, RR, and RPP from baseline |

RCT, Randomized control trial; DBP, diastolic BP; SBP, systolic BP; RPP, rate-pressure product.

In a well-written and well-designed paper, investigators reported on the effects of acupuncture on autonomic nervous system (ANS) function.79 Twelve healthy volunteers, six men and six women, ages 23 to 48 years, underwent randomized needle insertion into three distinct acupuncture sites. Measures of ANS function were monitored during the 25-minute intervention period and for the 60 minutes after intervention at each insertion site. An interesting combination of results was found, depending on the needle insertion site. Stimulation of the ear site resulted in increased PNS activity during both the needle insertion and the poststimulation periods. Stimulation of the skin over the left thenar muscle resulted in increased sympathetic nervous system (SNS) and PNS activity during both measurement periods. Stimulation of the right thenar muscle resulted in an increase in SNS and PNS activity during the poststimulation period, but no changes were seen during the needle insertion period. These results begin to shed light on which acupuncture interventions may be cardiosuppressive and possibly account for the calmness and relaxation often reported after treatment. Delayed responses may have a therapeutic effect as well.

In a controversial study by Rosa and colleagues (1998),80 the investigators failed to demonstrate that those practitioners of noncontact therapeutic touch were able to perceive a “human energy field.” Significant limitations to the study have been noted, including experimenter bias, inconsistent conclusions, and incomplete statistical analysis.81 Although this study does not address cardiovascular and pulmonary responses to therapeutic touch, it does provoke discussion about the difficulties of conducting research on this intervention.

A study by Haas and colleagues (1986)82 is worthy of mention in this discussion of energy interventions. These authors were able to demonstrate the ability of musical rhythm to “pace” respirations. In a sample of 20 healthy volunteers (half of whom were musically trained), breathing rhythms were correlated with metronome and tapping rhythms. This ability of musical rhythms to entrain respiration may have potential benefits in managing stress-induced respiratory patterns.

Risk Factors for Coronary Artery Disease

Numerous complementary therapies have been studied and shown efficacious in the management of known risk factors for coronary artery disease (CAD).83–85 Specifically, interventions addressing psychological stress and hypertension have been extensively examined.

Stress Reduction

First studied in the late 1970s and early 1980s, the benefits of meditation and the “relaxation response” have been recognized by Benson and colleagues (1977).86 They postulated that when properly applied, these interventions facilitated downregulation of the SNS and upregulation of the PNS.

During 15 to 30 minutes of practicing the relaxation response, changes in cardiovascular and pulmonary parameters have been noted. These include a decrease in RR and oxygen consumption ( ) and an increase in cardiac output (CO) without a concurrent increase in BP, reflecting a reduction in peripheral vascular resistance. In addition, skilled practitioners of the relaxation response demonstrate a decrease in

) and an increase in cardiac output (CO) without a concurrent increase in BP, reflecting a reduction in peripheral vascular resistance. In addition, skilled practitioners of the relaxation response demonstrate a decrease in  at a constant workload during treadmill activity.87

at a constant workload during treadmill activity.87

In an important paper addressing the impact of psychological factors on the development of cardiovascular disease, researchers related CAD to depression, anxiety, personality factors and character traits, social isolation, and chronic life stress.88 Several authors have addressed behavioral interventions effective in the management of these psychosocial stresses.

In a comprehensive metaanalysis of 70 articles, the treatment of trait anxiety with transcendental meditation (TM), progressive relaxation, relaxation response, and electromyographic (EMG) biofeedback were reviewed. Sources for the reviewed articles included journals, dissertations, and books. All interventions had a positive effect on self-reports or physiological measures of anxiety. Transcendental meditation had the strongest effect of the four interventions studied. In general, subjects who received more frequent interventions initially and who were followed the longest received the most benefit. It was recommended that future studies measure performance outcomes and that subjects be closely followed in an attempt to reduce loss due to attrition.89

Miller and colleagues (1995)90 reported on 22 subjects with anxiety disorders who participated in a noncontrolled clinical trial. Subjects were trained in mindfulness meditation, participated in a once-a-week group program for 8 weeks, and were followed-up for 3 years. Significant reductions in medications and counseling requirements were noted. The authors concluded that “mindfulness training … may be able to provide medical patients suffering from anxiety with a set of tools for achieving effective long-term non-pharmacological self-regulation … and be used as a complement to more conventional medical interventions.”90 Conversely, Astin (2003)30 reported an increase in anxiety levels in 17% to 31% of subjects practicing relaxation interventions and an increase in anxiety levels in up to 53.8% of subjects practicing TM. No negative medical consequences were reported as a result of the increased anxiety levels. Several causes for this negative response were postulated, including subjects’ fear of losing control, general restlessness, intrusive thoughts, and feelings of vulnerability.

Several small, noncontrolled clinical studies examining the effects of TM on blood levels related to cardiovascular disease have been reported. Infante and colleagues (2001)91 measured plasma catecholamine levels (epinephrine, norepinephrine, and dopamine) in 19 skilled practitioners of TM. Resting values were compared with catecholamine levels in nonmatched controls. Results demonstrated lower values in the skilled practitioners when compared with the controls. The authors concluded TM may have been responsible for the lower catecholamine levels and consequent downregulation of the SNS. Similarly, Schneider and colleagues (1998)92 concluded that TM may have been responsible for lower serum lipid peroxide levels found in 18 practitioners of TM compared with higher levels found in 23 nonmatched, nonpracticing control subjects. Lipid peroxide has been implicated in the pathophysiology of atherosclerosis.

Cognitive approaches to the reduction of stress have been subjected to clinical study. McCrone and colleagues (2001)93 compared the effectiveness of psychoeducational interventions on 33 male subjects with risk factors for CAD. In addition to nutrition counseling and exercise training, educational sessions addressing cardiovascular disease, risk factors, and stress reduction were offered to 25 participants. These subjects were also trained to use specific skills to improve their responses to stress and were given audiotapes to practice progressive muscle relaxation. Eight subjects in the nonrandomized control group received weight management counseling and health education only and did not participate in any discussions related to stress management. All subjects, ranging in age from 57 to 79 years, participated in the interventions for 6 months. Although both groups showed improvements in risk factor profiles, improvement was greater in the group trained in stress management interventions. Significant improvements were noted in BP, lipid profile, obesity indices, and fitness level.

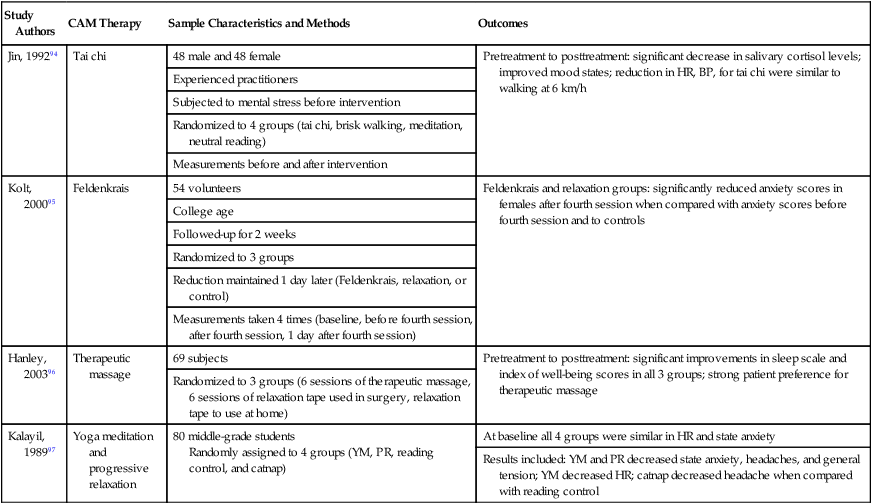

In spite of a positive theoretical basis for the use of CAM therapies in stress management, many interventions have not been subjected to systematic investigation. Table 27-4 summarizes the effects of tai chi, Feldenkrais method, yoga, and therapeutic massage in stress management. Although these four studies have significant methodological weaknesses, the number of subjects participating in each study is formidable. These initial attempts at providing efficacy of the respective intervention help suggest a launching ground for future study.

Table 27-4

Effect of Selected CAM Therapies in Stress Management in Healthy Individuals

| Study Authors | CAM Therapy | Sample Characteristics and Methods | Outcomes |

| Jin, 199294 | Tai chi | 48 male and 48 female | Pretreatment to posttreatment: significant decrease in salivary cortisol levels; improved mood states; reduction in HR, BP, for tai chi were similar to walking at 6 km/h |

| Experienced practitioners | |||

| Subjected to mental stress before intervention | |||

| Randomized to 4 groups (tai chi, brisk walking, meditation, neutral reading) | |||

| Measurements before and after intervention | |||

| Kolt, 200095 | Feldenkrais | 54 volunteers | Feldenkrais and relaxation groups: significantly reduced anxiety scores in females after fourth session when compared with anxiety scores before fourth session and to controls |

| College age | |||

| Followed-up for 2 weeks | |||

| Randomized to 3 groups | |||

| Reduction maintained 1 day later (Feldenkrais, relaxation, or control) | |||

| Measurements taken 4 times (baseline, before fourth session, after fourth session, 1 day after fourth session) | |||

| Hanley, 200396 | Therapeutic massage | 69 subjects | Pretreatment to posttreatment: significant improvements in sleep scale and index of well-being scores in all 3 groups; strong patient preference for therapeutic massage |

| Randomized to 3 groups (6 sessions of therapeutic massage, 6 sessions of relaxation tape used in surgery, relaxation tape to use at home) | |||

| Kalayil, 198997 | Yoga meditation and progressive relaxation | 80 middle-grade students Randomly assigned to 4 groups (YM, PR, reading control, and catnap) |

At baseline all 4 groups were similar in HR and state anxiety |

| Results included: YM and PR decreased state anxiety, headaches, and general tension; YM decreased HR; catnap decreased headache when compared with reading control |

Hypertension

There is a significant body of literature that addresses the benefits of CAM interventions in the management of hypertension (HTN). The majority of the larger studies address mind/body interventions, with most demonstrating positive effects on BP. In 1999 the Canadian Hypertension Society and the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada published guidelines recommending “individualized cognitive behavior modification to reduce the negative effects of stress.”98

Eisenberg and colleagues (1993)99 performed a metaanalysis addressing the effectiveness of cognitive behavioral therapies on HTN. Interventions accepted in this review were biofeedback, meditation, the relaxation response, progressive relaxation techniques, and stress management interventions such as imagery. They collected more than 800 published papers; however, because of methodological problems in the majority of papers, their limited inclusion criteria of adult subjects with diastolic BP of 90 to 114 mm Hg, lack of randomized control design, weak description of the study, and poor reporting of BP values, only 26 studies were entered for detail review. Results of this comprehensive analysis of 1264 patients indicated superior outcomes in the group receiving cognitive intervention techniques when compared with controls. No one intervention demonstrated more favorable outcomes than any other. In addition, when control groups were subjected to a placebo intervention (i.e., sham biofeedback), no significant differences in outcomes were noted. This is consistent with the belief that an intervention effect is inherent in the concept of placebo.31

In two RCTs of African American subjects, investigators examined the effects of stress reduction approaches on HTN. In one study, 111 males and females with mean BP of 147/92 mm Hg and mean age of 67 years were randomized to a 3-month trial of TM and progressive muscle relaxation (PMR) or a lifestyle modification education control program.100 Results demonstrated that TM had a greater effect at lowering both systolic and diastolic BP than did PMR and that both intervention groups demonstrated a significantly greater impact on BP reduction than did the control group. In a small but well-designed study, Barnes and colleagues (2001)101 recruited 34 African American adolescents (ages 15 to 18 years) with high-normal BP (>85th and <95th percentile for age and sex, respectively. After randomization, 17 subjects participated in 2 months of daily, 15-minutes sessions of TM. The control group attended seven weekly, 1-hour lessons on health education. Measures of cardiovascular function were collected at rest and during performance of a stressful activity (at baseline and again at the end of the intervention period). Although no significant changes were noted in resting values, results indicated that individuals in the TM group responded more favorably to stressor activities. Blood pressure increased appropriately during the activity in both groups; however, the degree of elevation was reduced in the TM group when compared with controls.

Reduction in antihypertensive medication requirements has been reported when mind/body therapies are added to the management regimen of HTN. In an RCT, Shapiro and colleagues (1997)102 studied 39 individuals with medically treated HTN. Subjects trained in cognitive behavior therapies (i.e. PMR, biofeedback, deep diaphragmatic breathing, and imagery) showed a 73% reduction of BP medication requirements during the study follow-up period compared with a 35% reduction in the control group. In addition, 55% of subjects in the intervention group were completely free of medication compared with only 30% of subjects in the control group. The reduction in BP levels was consistent across clinical, ambulatory, and home settings.

Yucha and colleagues (2004)103 reviewed 20 RCTs investigating the effects of biofeedback on HTN. Several forms of biofeedback, including thermal, EMG, and electrodermal, resulted in reductions in blood pressure when the intervention was combined with related cognitive therapy and relaxation training. When biofeedback was the sole intervention, significant reductions in BP were not demonstrated. Wang and colleagues (2004)104 performed a systematic review of the effects of tai chi on chronic conditions, including HTN. They reported on four moderate-sized studies: two randomized controlled trials and two nonrandomized controlled trials. Outcomes of all four studies indicated significant reduction in BP in older individuals and in those recovering from acute MI.

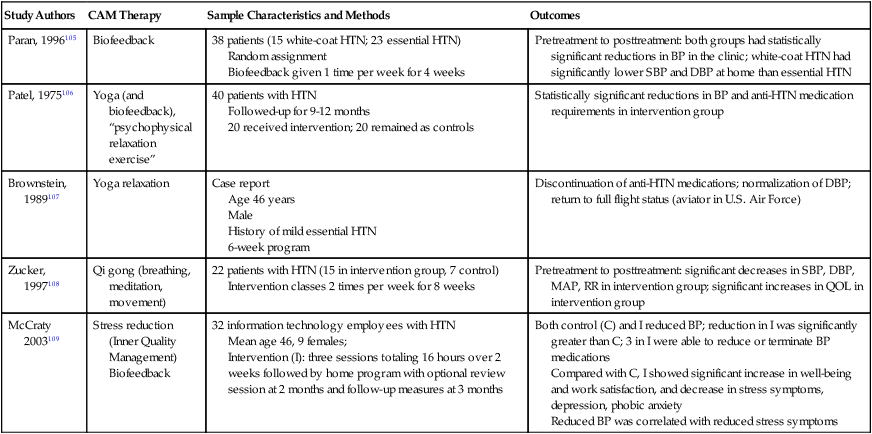

In addition to the mind/body therapies discussed above, several additional studies investigating the effects of select CAM therapies in individuals with HTN are summarized in Table 27-5. Although the evidence presented in these studies is weak, these investigations provide valuable insights to consider when structuring future research protocols. Several review articles addressing effects of other interventions are summarized in Table 27-6. In general, the results of these investigations assist in providing evidence for the benefit of the intervention in the management of HTN. In one review, Levin and Vanderpool (1989)110 consider the beneficial effects of religious commitment and affiliation in the management of HTN. Possible explanations offered for lower blood pressure in individuals with HTN include the psychosocial effects of membership in an organized religious community, the inherent health promotion behaviors and preferences often supported by religious traditions, and the psychodynamics of religious rites, faith, and belief systems.

Table 27-5

Effect of Selected CAM Therapies in the Management of HTN

| Study Authors | CAM Therapy | Sample Characteristics and Methods | Outcomes |

| Paran, 1996105 | Biofeedback | 38 patients (15 white-coat HTN; 23 essential HTN) Random assignment Biofeedback given 1 time per week for 4 weeks |

Pretreatment to posttreatment: both groups had statistically significant reductions in BP in the clinic; white-coat HTN had significantly lower SBP and DBP at home than essential HTN |

| Patel, 1975106 | Yoga (and biofeedback), “psychophysical relaxation exercise” | 40 patients with HTN Followed-up for 9-12 months 20 received intervention; 20 remained as controls |

Statistically significant reductions in BP and anti-HTN medication requirements in intervention group |

| Brownstein, 1989107 | Yoga relaxation | Case report Age 46 years Male History of mild essential HTN 6-week program |

Discontinuation of anti-HTN medications; normalization of DBP; return to full flight status (aviator in U.S. Air Force) |

| Zucker, 1997108 | Qi gong (breathing, meditation, movement) | 22 patients with HTN (15 in intervention group, 7 control) Intervention classes 2 times per week for 8 weeks |

Pretreatment to posttreatment: significant decreases in SBP, DBP, MAP, RR in intervention group; significant increases in QOL in intervention group |

| McCraty 2003109 | Stress reduction (Inner Quality Management) Biofeedback |

32 information technology employees with HTN Mean age 46, 9 females; Intervention (I): three sessions totaling 16 hours over 2 weeks followed by home program with optional review session at 2 months and follow-up measures at 3 months |

Both control (C) and I reduced BP; reduction in I was significantly greater than C; 3 in I were able to reduce or terminate BP medications Compared with C, I showed significant increase in well-being and work satisfaction, and decrease in stress symptoms, depression, phobic anxiety Reduced BP was correlated with reduced stress symptoms |

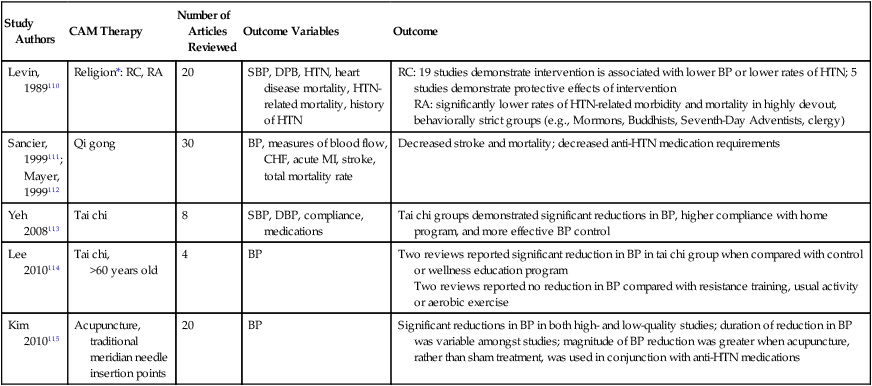

Table 27-6

Select CAM Therapies and their Effects on HTN: Summary of Review Papers

| Study Authors | CAM Therapy | Number of Articles Reviewed | Outcome Variables | Outcome |

| Levin, 1989110 | Religion*: RC, RA | 20 | SBP, DPB, HTN, heart disease mortality, HTN-related mortality, history of HTN | RC: 19 studies demonstrate intervention is associated with lower BP or lower rates of HTN; 5 studies demonstrate protective effects of intervention RA: significantly lower rates of HTN-related morbidity and mortality in highly devout, behaviorally strict groups (e.g., Mormons, Buddhists, Seventh-Day Adventists, clergy) |

| Sancier, 1999111; Mayer, 1999112 | Qi gong | 30 | BP, measures of blood flow, CHF, acute MI, stroke, total mortality rate | Decreased stroke and mortality; decreased anti-HTN medication requirements |

| Yeh 2008113 | Tai chi | 8 | SBP, DBP, compliance, medications | Tai chi groups demonstrated significant reductions in BP, higher compliance with home program, and more effective BP control |

| Lee 2010114 | Tai chi, >60 years old |

4 | BP | Two reviews reported significant reduction in BP in tai chi group when compared with control or wellness education program Two reviews reported no reduction in BP compared with resistance training, usual activity or aerobic exercise |

| Kim 2010115 | Acupuncture, traditional meridian needle insertion points | 20 | BP | Significant reductions in BP in both high- and low-quality studies; duration of reduction in BP was variable amongst studies; magnitude of BP reduction was greater when acupuncture, rather than sham treatment, was used in conjunction with anti-HTN medications |

RC, Religious commitment; RA, religious affiliation.

*Measures of religion include religious attendance, church membership, religious affiliation, ethnic traditions within Judaism, monastic orders, clergy status, religious education, and subjective religiosity.

In the review articles of the effects of qi gong in HTN, authors acknowledge significant methodological weaknesses in many of the studies reviewed.111,112 Some of the reported weaknesses include selection biases, lack of randomization, noncompliance with the intervention, concerns regarding BP measurement reliability, and the differences among the many styles of qi gong, which were not typically considered. Two review articles on the effects of tai chi on HTN are included in Table 27-6. Significant improvement in BP was reported in the eight studies reviewed by Yeh and colleagues (2008).113 Lee and colleagues (2010)114 found conflicting results in their review; they attributed their inconsistent outcomes to inadequate baseline BP testing in all four of the studies reviewed (one study was common to both of these reviews). Finally, Kim and colleagues (2010)115 presented a thorough review of 20 articles on the effects of acupuncture on HTN. They acknowledged that 17 of the 20 studies were poor quality and concluded that further “rigorously designed studies” are needed.115 Of note, no significant adverse reactions were documented in any of the tai chi or acupuncture articles reviewed.

Cardiovascular Conditions

Much of the pathophysiological basis for applying CAM therapies to cardiovascular conditions rests in the relationship between the cardiovascular system and the ANS.116 Stimulation of the ANS, specifically the SNS, can cause both an increase in circulating levels of catecholamines and damage to endothelial cells lining arterial walls. Often triggered by psychological factors, the resulting increase in metabolic and myocardial oxygen demand has a negative impact on the oxygen transport system.88 Interventions that can reduce or reverse these responses to SNS stimulation have a potential positive effect on cardiovascular conditions. Recently, a number of authors have looked at the impact of various CAM interventions on heart rate variability (HRV).117–121 The variability in R-R intervals between normal sinus rhythm cardiac cycles reflects the balance of SNS and PNS cardiac control. Low HRV has been associated with disease, whereas high HRV tends to indicate cardiovascular health and improved prognosis. In addition, patterns of HRV appear to reflect alterations in emotions and have been used to further demonstrate cardiovascular physiological responses to CAM interventions.122

Coronary Artery Disease

Beneficial effects of CAM interventions in the use of CAD management are documented throughout the published literature.29,30,32,123–125 Although significant methodological problems are apparent in many papers, numerous large, well-designed studies can be found. Much of the evidence supporting the use of these interventions in individuals with CAD demonstrates improvement in exercise tolerance, reduction of ischemia, and reduction of anxiety and depression. Mind/body techniques, including cognitive behavioral interventions, yoga, tai chi, guided imagery, and music therapy, have been successfully used in patients with CAD. The benefits of energy work, including distant healing prayer and qi gong, in patients with CAD have been reported.

In 1959, Friedman and Rosenman126 first documented the relationship between certain emotional behaviors and the prevalence of CAD.127 They defined the type A behavior pattern as “an emotional syndrome characterized by a continuously harrying sense of time urgency and easily aroused free-floating hostility.”127 In subsequent decades, the study of interventions aimed at modifying the behavior of individuals with type A behavior pattern and CAD was undertaken.

In a large study of post-myocardial infarction (MI) patients with type A behavior, 1013 subjects were randomized into three groups.127 Of the total, 270 subjects received group cardiac counseling, 592 subjects received both cardiac counseling and type A behavioral counseling, and the remaining 151 individuals did not receive any counseling. Subjects were followed for  years to determine the impact of type A behavior counseling on recurrent coronary events (both nonfatal infarctions and cardiac deaths). Cardiac counseling sessions consisted of 90-minute group meetings during which diet, exercise, medications, cardiovascular pathophysiology, and possible surgical procedures were discussed. Type A behavioral counseling sessions included progressive muscle relaxation, as well as specific psychotherapeutic interventions. Results indicated statistically significant reductions in recurrence rates of cardiac events in both intervention groups, with a greater reduction in the rate of recurrent events in those subjects who received both forms of counseling.

years to determine the impact of type A behavior counseling on recurrent coronary events (both nonfatal infarctions and cardiac deaths). Cardiac counseling sessions consisted of 90-minute group meetings during which diet, exercise, medications, cardiovascular pathophysiology, and possible surgical procedures were discussed. Type A behavioral counseling sessions included progressive muscle relaxation, as well as specific psychotherapeutic interventions. Results indicated statistically significant reductions in recurrence rates of cardiac events in both intervention groups, with a greater reduction in the rate of recurrent events in those subjects who received both forms of counseling.

In a landmark study of 48 patients with known CAD, Ornish and colleagues (1990)11 analyzed the number of coronary artery lesions detected at angiography before and after a year-long lifestyle intervention. In addition to a low-fat vegetarian diet, smoking cessation, and a moderate exercise program, subjects participated in a stress management training program of guided imagery. At the end of the year, the 28 subjects in the intervention group demonstrated statistically significant fewer coronary lesions than the 20 subjects in the usual-care control group. The regression in coronary atherosclerosis was attributed to the comprehensive lifestyle changes, brought about without the assistance of lipid-lowering medications. Clinical reports of angina were reduced as well.

Upon recognition of the impact of emotions on the recurrence rate of cardiac events in individuals with CAD, behavioral interventions became routine therapies in cardiac care.33 Dusseldorp and colleagues (1999)128 published a metaanalysis of the results of 37 studies investigating the effects of psychoeducational programs on patients with known CAD. All studies were conducted between 1974 and 1997 and were categorized according to stress management (SM) and health education (HE) interventions. Interventions used included various combinations of education, cognitive-behavioral therapies, relaxation, imaging, and emotional support. A number of studies included SM and HE interventions in combination with standard exercise training programs typically found in traditional cardiac rehabilitation programs. Results from studies administering either SM or HE intervention suggested a 34% reduction in fatal cardiac events and a 29% reduction in recurrent MI. The authors concluded that although psychoeducational therapies should be encouraged in cardiac rehabilitation programs, future research focusing on specific SM or HE interventions is warranted. In another metaanalysis addressing the effects of psychosocial interventions in subjects with CAD, Linden and colleagues (1996)129 reviewed 23 studies of 2024 patients and 1156 control subjects. In addition to the typical education component of cardiac rehabilitation programs, almost half of the studies included in this analysis involved some form of CAM treatment as an intervention. These included relaxation, breathing relaxation, and music therapy. Just as in the aforementioned metaanalysis, the benefits of adding a psychosocial component to these cardiac rehabilitation programs significantly reduced morbidity and mortality and psychological distress.

In 2000, in a scientific statement presented by the American Heart Association and the American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation, psychosocial management was identified as a “core component of cardiac rehabilitation/secondary prevention programs.”130 Suggested interventions included “individual and/or small group education and counseling regarding adjustment to coronary heart disease, stress management, and health-related lifestyle change … supportive rehabilitation environment and community resources to enhance patient’s and family’s level of social support.”130

The relationship between mental stress and myocardial ischemia in men with CAD has been well studied. Investigators have found an increased likelihood of having mental–stress-induced ischemia in individuals who experience daily life ischemia.131 Individuals with chronic anxiety and depression also exhibit more episodes of myocardial ischemia than those without documented anxiety and depression.132 In a 5-year, nonrandomized controlled study of 94 men with documented mental–stress-induced ischemia, researchers reported on the usefulness of a stress management program.133,134 In addition to educational classes, the intervention group received instruction aimed at reducing the physiological effects of stress. This included instruction in progressive muscle relaxation and individual sessions of EMG biofeedback. Outcomes of recurrent cardiac events were significantly reduced in the stress management group when compared with the control group at 1-, 2-, and 5-year follow-up. Overall reductions in hostility and clinical depression were also reported as statistically and clinically significant. The 5-year financial burden, including hospitalization and physician costs, was also significantly less in the stress management group. Similar results were reported by Zamarra and colleagues (1996)135 in a small, nonrandomized controlled study of the effects of an 8-month trial of TM. At follow-up bicycle exercise testing, participants demonstrated increases in exercise duration and maximal workload achieved and a delay in the onset of ST depression. In an early paper, Benson and colleagues (1975)136 reported on the beneficial effects of the relaxation response in reducing the number of premature ventricular contractions (PVC) in individuals with stable CAD. Subjects in this report practiced the relaxation response for 20 minutes, twice a day. Frequency of PVCs was documented by Holter monitor at baseline and again after 4 weeks.

In a thorough review Villagomeza (2006)137 explored the impact of spirituality in patients with heart disease. Twenty-six studies were discussed and included patients with acute MI, coronary artery bypass graft surgery, congestive heart failure, and heart transplant. Definitions of spirituality were listed for all articles reviewed. Most studies were descriptive or observational, and most measurement instruments were interview- and questionnaire-based; several studies used physiological and performance-based measurements. The author did not focus any conclusions on the effects of “spirituality” on heart disease but rather addressed a framework from which spirituality could be more easily studied. Irrespective of the definition of spirituality used in the 26 reviewed papers, the impact on outcomes appeared favorable.

Several studies have demonstrated no or limited improvements in cardiovascular outcomes with the intervention of specific behavioral therapies. In a large (n = 2328) RCT of early post-MI intervention, investigators reported limited benefit of psychological counseling.138 In this 2-year follow-up study, patients with acute MI returned within 28 days of the acute event to participate in 7 weeks of outpatient counseling, including PMR and skills to reduce stress. Subjects in the intervention group experienced significantly fewer episodes of angina; however, mortality, clinical complications, and clinical sequelae of CAD did not differ between groups. The authors concluded that the intervention was conducted too soon after the cardiac event, possibly accounting for the reduced treatment effect. In a study of patients participating in a phase II cardiac rehabilitation program, progressive muscle relaxation and guided imagery interventions failed to result in beneficial outcomes.139 Although there were methodological limitations in this paper, the authors similarly concluded the timing of the interventions may have contributed to the absence of benefit.

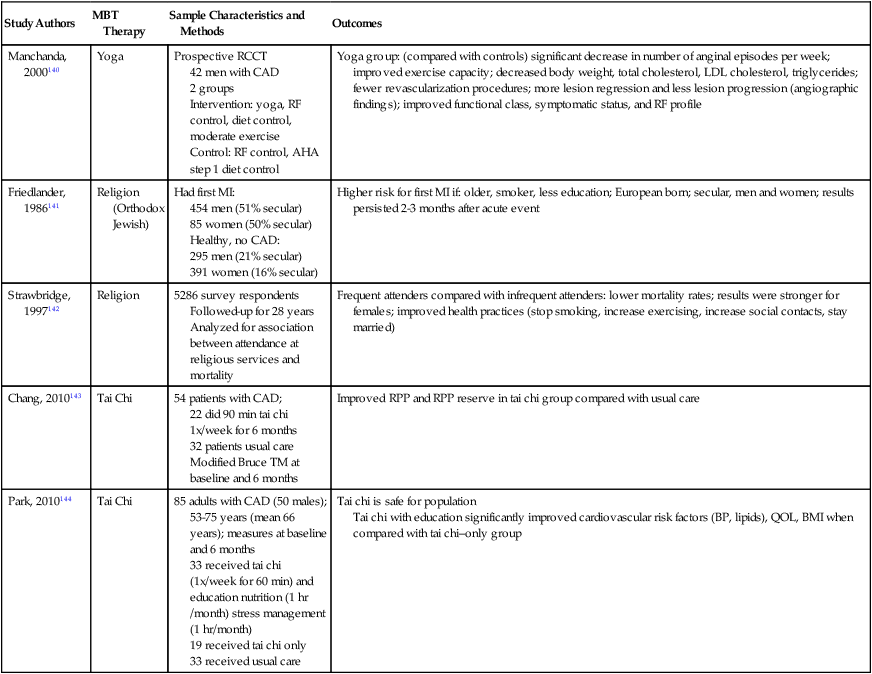

Results of the effects of selected mind/body therapies in CAD are summarized in Table 27-7. Manchanda and colleagues (2000)140 investigated the effects of yoga on numerous cardiovascular measures. Although improved outcomes were documented in the intervention group when compared with controls, the demonstrated benefits may be due to the moderate exercise component of the intervention and not necessarily the yoga component.

Table 27-7

Effect of Selected Mind/Body Therapies in CAD

| Study Authors | MBT Therapy | Sample Characteristics and Methods | Outcomes |

| Manchanda, 2000140 | Yoga | Prospective RCCT 42 men with CAD 2 groups Intervention: yoga, RF control, diet control, moderate exercise Control: RF control, AHA step 1 diet control |

Yoga group: (compared with controls) significant decrease in number of anginal episodes per week; improved exercise capacity; decreased body weight, total cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, triglycerides; fewer revascularization procedures; more lesion regression and less lesion progression (angiographic findings); improved functional class, symptomatic status, and RF profile |

| Friedlander, 1986141 | Religion (Orthodox Jewish) |

Had first MI: 454 men (51% secular) 85 women (50% secular) Healthy, no CAD: 295 men (21% secular) 391 women (16% secular) |

Higher risk for first MI if: older, smoker, less education; European born; secular, men and women; results persisted 2-3 months after acute event |

| Strawbridge, 1997142 | Religion | 5286 survey respondents Followed-up for 28 years Analyzed for association between attendance at religious services and mortality |

Frequent attenders compared with infrequent attenders: lower mortality rates; results were stronger for females; improved health practices (stop smoking, increase exercising, increase social contacts, stay married) |

| Chang, 2010143 | Tai Chi | 54 patients with CAD; 22 did 90 min tai chi 1x/week for 6 months 32 patients usual care Modified Bruce TM at baseline and 6 months |

Improved RPP and RPP reserve in tai chi group compared with usual care |

| Park, 2010144 | Tai Chi | 85 adults with CAD (50 males); 53-75 years (mean 66 years); measures at baseline and 6 months 33 received tai chi (1x/week for 60 min) and education nutrition (1 hr /month) stress management (1 hr/month) 19 received tai chi only 33 received usual care |

Tai chi is safe for population Tai chi with education significantly improved cardiovascular risk factors (BP, lipids), QOL, BMI when compared with tai chi–only group |

Tai chi practice has been recommended as a therapeutic intervention in balance disorders and fall prevention in older adults.25,145,146 Its potential benefits as replacement for or as an adjunct therapy in cardiac rehabilitation programs have been suggested as well.143,144,147 In an interesting commentary in 1992, Ng stated that tai chi “has many similarities with … walking exercise—the most recommended aerobic exercise for coronary artery disease.”148 Further clinical study is warranted to provide evidence of the benefit of tai chi in the population with CAD.

Two papers addressed the use of several mind/body and manual therapies to assist with anxiety reduction in patients undergoing cardiac catheterization. McCaffrey and colleagues (2005)149 reported on the use of music therapy, massage, guided imagery, and therapeutic touch. These interventions were performed within the hour before the diagnostic procedure. Outcomes demonstrated reduction in BP, HR, and worry, along with improved mood, in the intervention group when compared with the control group. In another study, using a visual analogue scale, authors demonstrated that “PalmTherapy” was effective in reducing anxiety levels before the procedure. PalmTherapy is an intervention that uses continuous pressure on various points in the hand.150

There is minimal evidence available investigating the effects of energy work on patients with CAD. Several studies compared acupuncture to sham acupuncture in individuals with angina.151 Although no significant differences were noted in the number of anginal episodes or nitroglycerin use, the use of sham acupuncture has been questioned. As noted earlier, not all practitioners agree on proper needle location; hence what one practitioner thinks is an active acupuncture site may be considered a sham site to another practitioner. An interesting review of the effects of acupuncture on cardiac dysrhythmias was recently published.152 The authors considered the ineffectiveness of antiarrhythmic drugs in managing certain dysrhythmias and aimed to examine the impact of acupuncture on reducing these abnormal cardiac rhythms. They reported on eight studies; seven were case studies or case series, and one was a randomized controlled trial. A total of 150 subjects participated in the eight studies, and the mean age was 54 years. Male and female participants were included, and dysrhythmias, although diverse, were primarily supraventricular tachycardia, sinus bradycardia, and ventricular extrasystoles. All participants received antiarrhythmic medications in addition to acupuncture. Treatments ranged between 1 day and 6 months, and between 1 and 50 sessions; each session lasted an average of 20 minutes. The primary outcome measured in all studies was the frequency of dysrhythmia presentation or conversion to normal sinus rhythm. Between 87% and 100% of participants demonstrated improvement; no dropouts or adverse effects were reported. There were significant methodological weaknesses in many of the studies, which led the authors to conclude that future large, rigorous trials are warranted.

Another role for CAM therapies that address stress reduction in patients with CAD is based on the relationship between chronic stress and reduced immune system function. Individuals with depressed immune systems are more vulnerable to inflammatory processes, the latter recently implicated in CAD.153–155

Cardiac Surgery

The Complementary Care Center (CCC) at Columbia-Presbyterian Medical Center is a “multifaceted program dedicated to evaluating and researching the effects of new modalities in health care.”156 Since 1995, practitioners at this center have been evaluating and researching the effects of various types of CAM therapies. One area of intervention involves patients having cardiac surgery. Upon initial evaluation, these patients are offered several options to help with recovery and healing. Some of these modalities include meditation, music therapy, yoga, massage, and therapeutic touch. Audiotapes can be used at various times in the perioperative period, including 5 to 10 days preoperatively, intraoperatively, immediately postoperatively, and during the recuperation phase. Therapeutic touch has been offered on the day of surgery and on postoperative days 2 and 3. Group yoga classes are offered to those patients who are medically stable as early as the third postoperative day. In addition, patients are encouraged to contact a religious leader of their choice. Continuation of these therapies is offered to the patient after hospital discharge. Patients can choose to attend sessions at the center or at a more convenient site.

The innovative approach used at the CCC resonates with the philosophy of increasing the patient’s participation in his or her health and healing. Liu and colleagues (2000)157 have reported on the use of CAM therapies in 376 consecutive patients undergoing cardiac surgery. Patients were surveyed before surgery, and 75% reported using CAM therapies. When prayer and vitamins were excluded, 44% reported using CAM therapies. Seventy-two percent of subjects were male, 76% were white, and 59% were well educated. No differences in overall CAM use were found among sex, age, race, or education level. The authors did offer an important recommendation. They noted that only 17% of patients had discussed their use of CAM therapies with their physicians, and 48% of patients did not want to discuss the topic at all. Since the frequency of CAM use found in this sample was consistent with the frequency of CAM use reported in the general population, the authors reinforced the importance of questioning patients about their use of CAM therapies.158

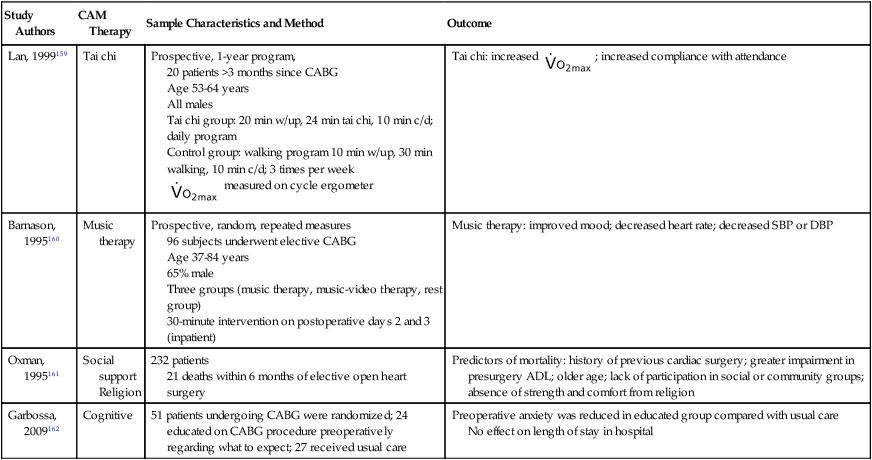

Evidence supporting the use of selected CAM therapies perioperatively is found in Table 27-8. Although methods were not always comprehensive in these studies, all demonstrated improvement in cardiovascular outcomes. In the study by Barnason and colleagues (1995)160 the authors concluded that effects of the music therapy on outcomes were consistent with a relaxation response, and in the study by Garbossa (2009),162 authors concluded that education and instruction in hospital routine significantly reduced preoperative anxiety when compared with control subjects.

Table 27-8

Effects of Selected CAM Therapies on Outcomes of Cardiovascular Surgery

| Study Authors | CAM Therapy | Sample Characteristics and Method | Outcome |

| Lan, 1999159 | Tai chi | Prospective, 1-year program, 20 patients >3 months since CABG Age 53-64 years All males Tai chi group: 20 min w/up, 24 min tai chi, 10 min c/d; daily program Control group: walking program 10 min w/up, 30 min walking, 10 min c/d; 3 times per week  measured on cycle ergometer measured on cycle ergometer |

Tai chi: increased  ; increased compliance with attendance ; increased compliance with attendance |

| Barnason, 1995160 | Music therapy | Prospective, random, repeated measures 96 subjects underwent elective CABG Age 37-84 years 65% male Three groups (music therapy, music-video therapy, rest group) 30-minute intervention on postoperative days 2 and 3 (inpatient) |

Music therapy: improved mood; decreased heart rate; decreased SBP or DBP |

| Oxman, 1995161 | Social support Religion |

232 patients 21 deaths within 6 months of elective open heart surgery |

Predictors of mortality: history of previous cardiac surgery; greater impairment in presurgery ADL; older age; lack of participation in social or community groups; absence of strength and comfort from religion |

| Garbossa, 2009162 | Cognitive | 51 patients undergoing CABG were randomized; 24 educated on CABG procedure preoperatively regarding what to expect; 27 received usual care | Preoperative anxiety was reduced in educated group compared with usual care No effect on length of stay in hospital |

In another small but clinically important study, Miller and Perry (1990)163 examined the benefit of a deep-breathing relaxation technique on pain tolerance in patients undergoing cardiac surgery. On the evening before surgery, 15 subjects were taught a slow, rhythmic, deep-breathing relaxation technique in addition to traditional preoperative instruction. The remaining 14 subjects only received the traditional preoperative instruction. All subjects were visited by the investigators on the day of surgery and on postoperative day 1 for conversation; however, only subjects in the intervention group were encouraged to perform the relaxation technique. Patients in the relaxation group had significant decreases in systolic and diastolic BP, HR, RR, and self-report of pain (on visual descriptor scale) when compared with controls. The authors concluded that “relaxation techniques may interrupt the pain-anxiety cycle” and that, although there were methodological problems with their study, this “may be an effective non-narcotic, noninvasive pain-relieving modality after” cardiac surgery. Additional study of the relaxation response has demonstrated a reduction in postoperative arrhythmias, as well as reduced tension and anger in patients undergoing cardiac surgery.32

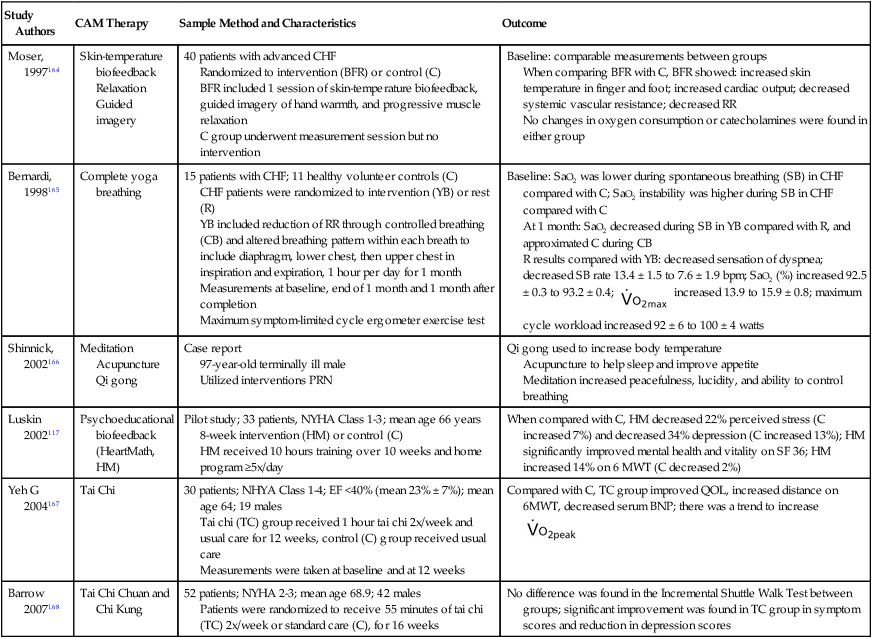

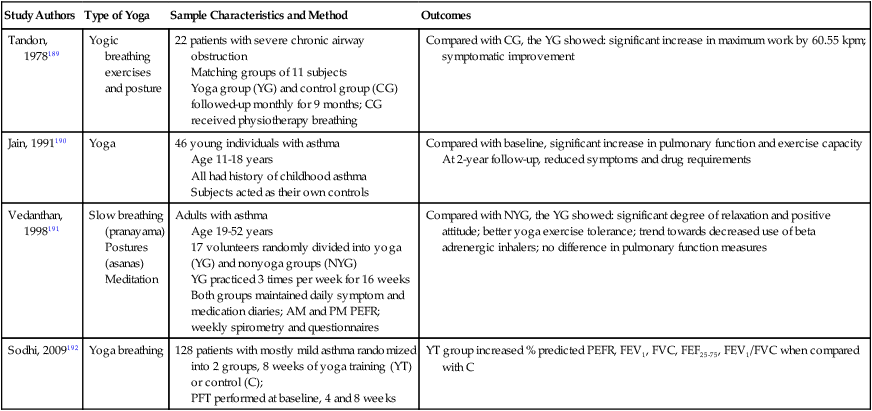

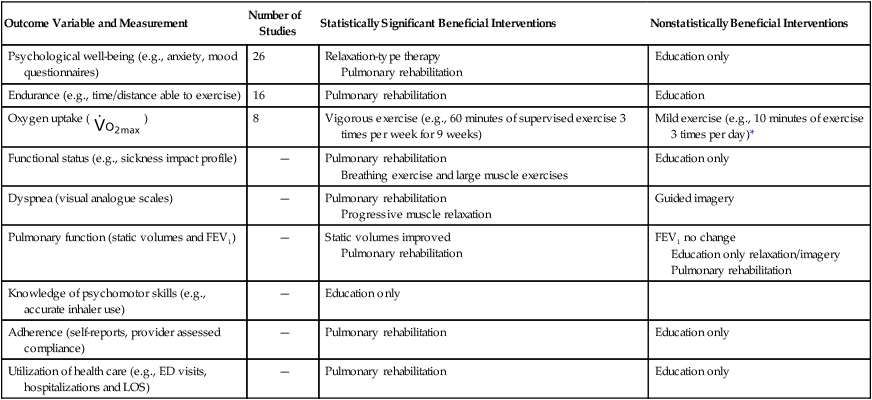

Congestive Heart Failure