Complementary and alternative therapies: beyond traditional approaches to intervention in neurological diseases and movement disorders

DARCY A. UMPHRED, PT, PhD, FAPTA, CAROL M. DAVIS, DPT, EdD, MS, FAPTA and MARY LOU GALANTINO, PT, PhD, MSCE

After reading this chapter the student or therapist will be able to:

1. Differentiate the four historical to modern worldviews of health care delivery.

2. Analyze how complementary and alternative-based health care practices overlap with allopathic traditional medical models and movement diagnoses.

3. Analyze how mind, body, and spiritual interactions have the potential to lead to health, healing, and quality of life.

4. Compare and contrast the various therapeutic models discussed and identify similarities and differences between these and the traditions of Western medicine, OT and PT practice, and the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) World Health Organization (WHO) model.

5. Appreciate the role of complementary and alternative approaches in the examination and intervention of individuals with movement-based problems as a result of neurological disorders.

6. Use evidence-based practice to measure outcomes in body system functions, functional activities, and life participation.

The use of complementary and alternative methods (CAMs) in the treatment of patients with neurological disorders and resultant movement problems is evolving into common practice. Clinicians and patients/clients are seeking nontraditional approaches to relieve signs and symptoms of neurological diseases, syndromes, and movement disorders as well as to attempt to alter the progression of diseases of the central nervous system (CNS) through unconventional movement therapies and manual therapeutic approaches. It is important that professionals working within a traditional rehabilitation environment understand the principles and practices of complementary, alternative, and even transdisciplinary approaches to the treatment of movement problems because many of these therapeutic approaches are being proposed as options in the management of body system problems and restrictions in daily life activities and independence resulting from neurological problems. The clinician needs to be cautious in the application of these treatment modalities. We do not want to accept alternative therapies as intervention solutions without significant evidenced-based research substantiating the use of these approaches. The reader must also be reminded that evidence comes from effectiveness, and many complementary approaches have established effectiveness.1

Historical perspective

Looking at the evolution of health care throughout the world over hundreds and even thousands of years, general categories or worldviews have developed that best categorize philosophy of management of individuals with health care issues and their respective rationales for practice. In the following paragraphs a further discussion of these four worldviews will help the reader identify how the practice of health care today still fits within the second worldview but has begun to fractionate into the third worldview as linear research based on two variables does not explain the multiple variables involved both in disease or pathology and in recovery of function. In their book The Second Medical Revolution, Laurence Foss and Kenneth Rothenberg described levels of academic learning as being three tiered.2,3 Starting at the top, the third tier comprises the applied studies and subjects for therapists, such as therapeutic exercise and electrotherapy. The second tier is the pure sciences on which these subjects are founded, such as anatomy, chemistry, physiology, and biology. The first tier is the “assumption of reality” (day-to-day observations) on which the pure sciences are based. This first tier consists of the basic assumptions found in “worldviews” today. Different worldviews yield different scientific bases, whether pure or applied. Alternative approaches used in medicine and rehabilitation are well established in “premodern” and “postmodern” worldviews. This is in contrast to the “modern worldview” customarily taught in current Western medical training. To present these methods in overview, it would be helpful to discuss these worldviews and how physical therapy (PT) and occupational therapy (OT) may fit into the scheme.

Essentially, there are four worldviews4: the premodern, modern, “fracturing or splintering,” and postmodern views. The first worldview developed during prehistoric times and lasted until the sixteenth century. This is called the premodern view. In this perspective, time is cyclical rather than linear. In other words, it was believed that the sun, the moon, and the stars circle around the earth, the tides ebb and rise cyclically, and the seasons circle back again and again, using the same patterns each time, connecting with “deep time.” Deep time is compared with profane time. Profane time is tangible, as in the time it takes rice to boil; or visible, as in the sundial; or sensible, as in the heartbeat. In deep time such perceptions are suspended, profane time stands still, and one becomes a part of time. It is in deep time that premodern man finds reality. Infused in this thinking is that life and death, the earth and the sky, are mysterious or mystical. In other words, they contain truth beyond human comprehension.

This is a hard perspective for many to grasp, yet the role of the scientist is to be a passive observer. Numbers were used to describe observed events, such as the days between the circling of the sun and the moon, and the number of hours between the ebb and high tide, but “there was no widespread assumption in the western world that natural processes in general had any intrinsic relation to numbers, to mathematics.”5 In other words, in Western science, these perspectives were not tangible, visible, or sensible…and so, historically, science moved on.

The second worldview, which began with Copernicus, is known as the modern worldview. It is the one with which the majority of the Western population would be most familiar and feel at home. In this view time is linear, progressing from start to finish. “The world is a rational, predictable, clockwork universe. Every bit of it can be predicted if you know one part of it. Purpose in life is to describe, generalize, predict, and control. Human beings are fairly mechanistic, separate, discrete entities from the rest of the universe.”4

Worldview 4, postmodern, is complex, integrated, and nonlinear. It is about self-organizing and self-regulating systems, looking for patterns, and knowing that a small variation in the pattern can produce large changes. Time is a dimension, interwoven with the dimensions of space. Time and space can change, expand or shrink, speed up and slow down. Rituals are an important means for creating order. The whole is greater than the sum of the parts, and “we know and yet don’t know.” Worldview 4 has a lot of similarities with worldview 1. The pure sciences that arise from this worldview include systems theory, quantum physics, cybernetics, string theory, and fractal mathematics, which in turn affect many other fields of study, such as meteorology, ecology, business and economics, medicine, theology, movement science, and computer science, to name but a few. Research parameters, technology, and interpretation differ significantly from the assumptions of worldview 2 because scientific description is no longer considered purely objective, but rather epistemology (the view from which knowledge is gathered) is becoming “an integral part of every scientific theory.”6 Western medicine has begun to shift from the second worldview into the third worldview because a total linear approach to explain efficacy has not proven inclusive and cannot always explain why individuals do and do not recover from disease or pathology or the functional loss they produced. The professions of PT and OT have run into the same dilemma as Western medicine and are also making similar shifts. The incorporation of alternative or complementary approaches that take into consideration the mind, body, and spirit is becoming more acceptable as colleagues embrace the shift in thought process. Change will come. The rate and the depth of that change will depend on the openness of all of us to accepting different research methodology and outcomes while still embracing those linear research models of today that we believe lead to efficacy or evidence-based practice.

The roots of Western medicine extend back to Hippocrates, 400 bc, who provided a holistic picture of the state of health, writing that “Health depends upon a state of equilibrium among the various internal factors which govern the operations of the body and the mind, the equilibrium in turn is reached only when man lives in harmony with his external environment” (p. 23).2 The basic assumption in this perspective is that health depended on a balance with mind-body and nature or the environment, and disease was a disturbance of this balance. Preserving the balance was the priority for the practitioner. Three means were used to ascertain the characteristics of an illness: a dialogue with the patient, observational assessment of the patient’s appearance, and palpation of the soft tissues and pulses. The most important component of this approach was considered the dialogue with the patient/client. It was believed that the “meaning” of the illness to the patient/client, and his or her attitude and expectations were valuable diagnostic and prognostic factors. This coincides closely with the World Health Organization (WHO) International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) model accepted by rehabilitation professionals around the world.7

Descartes largely initiated the shift from a preservative approach for mind-body-environment integrity to the conventional curative thinking found in medicine today. He conceptualized reality as having two separate domains, one the body or matter, the other the mind. “The body is a machine,” said Descartes, “so built up and composed of nerves, muscles, veins, blood and skin, that though there were no mind in it at all, it would not cease to have the same [functions]” (p. 32).2 His ideas were closely tied to newtonian physics, which conceives the universe as a harmonious and well ordered machine. These concepts gave rise to the view that matter and nature were separate from humans, and thus one could observe without affecting what was being observed. The physician, then, could have complete objectivity when assessing the patient. The patient could be viewed as a biological organism whose function was reducible to interrelating physical parts.

1. Disease or dysfunction is a “deviation from the norm of measurable biological parameters” (p. 23).2 A patient/client is a biological organism whose dysfunction is reduced to the identified deviations. Treatments or procedures are then used to cure or at least improve the deviations, which in turn improves the biological condition.

2. Objectivity provides the basis for diagnosis or assessment and the subsequent rationale for treatment. Patients’/clients’ descriptions of what they are experiencing and the clinician’s observation are considered “subjective” and not given as great a value as the “objective” findings, such as laboratory or other measured tests.

3. Eventually biomedicine can address virtually all medical problems at least adequately, if not fully, through more knowledge and research.

It goes without saying that the biomedical model has produced stunning and tremendous accomplishments. Yet its restriction to physical causes of disease, in light of diseases and dysfunctions that are more widely recognized as having multiple causes, is creating a search for other answers. More of the public and some physicians and other health professionals are turning to alternative forms of intervention and healing. As stated in Life magazine in September 1996, “Why have alternative therapies in this country started to migrate from the margins to the center? One reason is that as allopathic medicine, a term commonly used to describe western techniques, becomes better at what it can do well, its limitations become more conspicuous. Allopathy is clearly superb at dealing with trauma and bacterial infections. It is far less successful with asthma, chronic pain and autoimmune diseases.”8

One of the tenets of dynamical systems theory, as noted in the journal of the American Physical Therapy Association (APTA) in 1990, is that “biological organisms are complex, multidimensional, cooperative systems. No one subsystem has logical priority for organizing the behavior of the system” (p. 770).9 The nervous system, then, is no longer a dominant subsystem with neurological patients. Rather, it is part of a self-organizing system that has multiple subsystems such as arousal, gravity, learning style, body weight, center of gravity, cardiovascular function, and so on. “No one subsystem contains the instructions for [an action]. . . . The behavior of the system is instead an emergent property of the interaction of multiple subsystems” (p. 771) (see Chapters 4 and 5).9

Added to these developments was the emergence in the 1980s of a new field of therapy intervention: vestibular habilitation for posture and balance, which is multisystem and multifunctional and inherently demands the use of motor control and learning principles and understanding of the mechanism of neuroplasticity and interactive systems theories. Systems concepts are used for both balance and the task-oriented approach, the concept being that “movement emerges from an interaction between the individual, the task, and the environment”10 (see Chapters 11 through 17 and 19 through 31).

Orthopedic, or manual, PT appears to be firmly committed to the biomedical model, yet there is interest found in “being holistic,” and treatment and exercise approaches are continually being developed that endeavor, to various degrees, to work with movement and function in a broader and more integrated manner (see Chapter 18).

Further changes will be experienced when a critical mass of the population turns fully, in all aspects of personhood, to “worldview 4,” which, again, has great similarities to worldview 1. A big difference, though, is that at this time in history, we have scientific methods for understanding our nonlinear, complex, evolving, multidimensional, multilevel, continually interacting, irreducible world. Through systems theory we can handle, with sophistication, this multitude of complex detail, by working with its “sweeping simplicity and order in overall design.”3 Throughout the twenty-first century, as the growth of worldview 4 continues to evolve on many levels and in many fields of endeavor, it is entirely possible that it and its sciences will indeed replace, and not simply complement, worldview 2. And from there, the future has yet to be conceptualized and belongs to future students willing to venture beyond what is comfortable to best meet the health care needs of a world society.

Alternative models and philosophical approaches

Approaches to patient management that do not fall within a traditional allopathic medical model are often considered alternative or complementary. Although many of these therapeutic approaches have not been able to show effectiveness or efficacy in totality as an approach to medical management, neither has Western medicine. Although the evidence-based method of medicine is the accepted term for identifying outcome measures by reliable and valid instrumentations and interventions, there is controversy within the literature as to the validity of evidence-based medicine.8–16 Personally, I have been a patient for the last two decades with interactive health issues that medical practitioners cannot explain. I have been told by at least seven excellent medical specialists that, when looking at their specific area of specialization, they have never seen the specific system problem that my body system presented. Thus, not knowing what it is, each doctor does not know specifically how to treat the problem. Medical doctors know there is some genetic basis and understand the specific system problem from a descriptive perspective, but cannot explain how and why the system problems interact. Thus a syndrome exists without a medical diagnosis. My medical case was submitted to the National Institutes of Health (NIH) as a potential syndrome for which they might find a diagnosis. NIH returned the case saying they do not have the ability to determine the diagnosis because it is much too complex. Doctors have had to stretch beyond their comfort zone to help me and work with me in order for me to remain on this plane we call life.

Movement therapy approaches

Equine-assisted therapy

Kerri Sowers, USEF National Paraequestrian Classifier

Introduction to hippotherapy and therapeutic riding.

At the 1952 Helsinki Olympic Games, a Danish dressage rider named Liz Hartel won the silver medal and inspired a renewed interest in the field of hippotherapy and therapeutic horseback riding (THR). Liz used horseback riding as a form of rehabilitation to aid her recovery from poliomyelitis, which left her lower extremities paralyzed.17,18 The use of horses in therapy to improve physical and mental health has its founding roots in Greek culture. The term hippotherapy originated from the Greek word hippos, meaning “horse.”19 The renewed interest in hippotherapy and THR grew first in Europe and was especially popular throughout England. In 1969, the North American Riding for the Handicapped Association (NARHA) was founded; this organization established standards for the developing THR centers in the United States.17–20 Recent studies conducted in North America show that approximately 90% of children with disabilities participate in THR programs, and the remaining 10% participate in hippotherapy sessions.21

It is crucial to understand the differences between hippotherapy and THR, as both programs are commonly offered at the same facility and are often mistakenly thought to accomplish the same goals. The American Hippotherapy Association (AHA) defines hippotherapy as “a term that refers to the movement of the horse as a tool by physical therapists, occupational therapists and speech-language pathologists to address impairments, functional limitations and disabilities in patients with neuromuscular dysfunction. Hippotherapy is used as part of an integrated treatment program to achieve functional outcomes.”20 During hippotherapy, the horse is used as a modality or treatment tool; the therapist and his or her assistants control the horse in order to effect a change in the patient/client. In contrast, THR teaches the client specific riding skills that allow the rider control of the horse’s movement; the focus is on teaching horseback riding skills to riders with disabilities. AHA attempts to clarify the difference by stating that hippotherapy “treatment takes place in a controlled environment where graded sensory input can elicit appropriate adaptive responses from the client. Specific riding skills are not taught as in therapeutic riding but rather, a foundation is established to improve neurological function and sensory processing.”20

Benefits, indications, and precautions.

Hippotherapy and THR are felt to be beneficial because the equine walk provides a multidirectional input resulting in movement responses that closely mimic the movement of the pelvis during the normal human gait. The movement is both rhythmic and repetitive and allows for variations in speed and cadence. In hippotherapy the horse is used as a dynamic base of support (BOS) to assist in improving trunk control, postural stability, core strength, and righting reactions to improve balance.22 Vestibular, proprioceptive, tactile, and visual sensory inputs are incorporated during a hippotherapy session. As stated by the AHA, “the effects of equine movement on postural control, sensory systems and motor planning can be used to facilitate coordination and timing, grading of responses, respiratory control, sensory integration skills and attentional skills.”22

Hippotherapy is indicated for neuromuscular conditions characterized by reduced gross motor skills, decreased mobility, abnormal muscle tone, impaired balance responses, poor motor planning, decreased body awareness, impaired coordination, postural instability or asymmetry, sensory integration deficits, impaired communication, and limbic system dysfunction (impaired arousal or attention skills).18,22,23

Common conditions that may benefit from hippotherapy and THR include autism spectrum disorder, cerebral palsy, developmental delay, genetic syndromes, learning disabilities, sensory integrational disorders, speech-language disorders, traumatic brain injury (TBI), and cerebral vascular accidents.22

There have been a multitude of suggested therapeutic benefits from hippotherapy and THR, which affect many body systems. Suggested physical benefits include improvements in endurance, symmetry, and body awareness; development of trunk and postural control; improvements in head righting and equilibrium responses; normalization of muscle tone; mobilization of the pelvis, lumbar spine, and hip joints; and improved sensory awareness. Suggested cognitive, social, and emotional benefits include improvement in self-esteem, confidence, interaction with others, concentration, attention span, and communication skills.18,19,24

Contraindications for the use of hippotherapy or THR include excessive hip adductor or internal rotator tone accompanied by potential hip subluxation or dislocation, lack of head control (in large children or adults), pressure sores, spinal instability, or anxiety around animals.18,24

Regulations.

AHA offers a Clinical Specialty Certification for therapists demonstrating advanced knowledge and experience in the practice of hippotherapy. Physical therapists, occupational therapists, and speech-language pathologists must have been practicing in their profession for 3 years (6000 hours) and have had 100 hours of hippotherapy practice within the 3 years prior to application. Certification is valid for 5 years; once applicants pass a multiple choice test they are entitled to used the designation HPCS.22,25

Evidence and clinical implications.

Research and studies concerning the use of hippotherapy and THR are limited but expanding. At the time of publication of this text, there have been no large, well designed, randomized controlled trials investigating the use of hippotherapy or THR. There have been several fair-quality randomized controlled trials and many nonrandomized trials that do support the use of hippotherapy in children with cerebral palsy. One systematic review investigating the use of hippotherapy and THR found improved gross motor function; normalization of pelvic motion; improvements in weight shifting, postural and equilibrium responses, muscle control, and joint stability; improved recovery from perturbations; and improved dynamic postural stabilization.21 Studies have supported that hippotherapy can improve postural stability in individuals with multiple sclerosis (MS) and can assist in treatment of balance disorders.26,27 Hippotherapy has also been shown to reduce lower-extremity spasticity in patients with spinal cord injury.28 Support for hippotherapy has been shown by improvements in the areas of muscle symmetry, gross motor function (as measured by valid and reliable tools), energy expenditure, and postural control. Researchers suggest that hippotherapy will lead to improved head righting and equilibrium reactions and dynamic postural control, normalization of abnormal muscle tone or symmetry, improved muscle control, and better endurance. In addition, hippotherapy has the potential to contribute to psychosocial well-being and improved motivation by allowing interaction and acceptance with another living being and the opportunity to be mobile while astride the horse; being positioned high up on a horse gives the child the chance to be at eye level with his or her peers, and the fun of riding encourages participation and enjoyment of the therapy sessions. Continued research into hippotherapy and THR using larger, randomized controlled studies that investigate specific outcomes and account for the variations within a variety of neuromusculoskeletal conditions will be necessary to conclusively determine all potential benefits that exist.

Feldenkrais method of somatic education

The Feldenkrais method is about learning the following:

I do not treat patients. I give lessons to help people learn about themselves. Learning comes from the experience. I tell them stories [and give them experiences of movement] because I believe learning is the most important thing for a human being” (p. 117).29 [parentheses added by the author].

Development of the feldenkrais method.

As a boy in Palestine, Moshe Feldenkrais developed a method of hand-to-hand combat that was used by settlers for self-defense. Later, as a student in Paris where he trained in physics at the Sorbonne, he studied judo and became the first person in Europe to receive a black belt. When he injured his knee playing soccer, he relearned pain-free walking on his own. Later he studied with F. M. Alexander, Elsa Gindler, and Gurdieff. He also studied psychology, progressive relaxation, bioenergetics, and the hypnosis methods of Milton Erickson. And he was familiar with the physiology of his day: Sherrington, Magnus, Fulton, and Schilder. With this background, Feldenkrais developed two approaches to facilitating learning that are now known as Awareness Through Movement (ATM) and Functional Integration (FI).30

Feldenkrais was ultimately interested in the development of human potential. He saw that, although all people encounter trauma and difficulty in their lives, those who are most successful develop new, adaptive behaviors to overcome those difficulties. He proposed that a type of learning that reconnected the brain to the control of the musculoskeletal system would be the most effective way to approach this problem of adaptation. His initial thinking in this area is set out in his first book, Body and Mature Behavior: A Study of Anxiety, Sex, Gravitation, and Learning.31

Background theory—dynamical systems theory.

For Feldenkrais, learning was an organic process in which cognitive and somatic aspects were completely integrated and interactive. Presented first in 1949, this idea prefigured our current sense of dynamic systems functioning of the brain and body.32 The learning should proceed at its own pace in an individualized way following the learner’s intention and guided by the learner’s perception that the performance of the task, movements of the body, and interaction with the environment become easier.31 This interactive cycle of action and perception has been described well by the motor learning model proposed by Newell.33

Learning is a complex process with overlays from the intention of the learner, interference from environmental distraction, misperception of the task and the body, desire related to self-image, fear of injury, or incorrect performance. Thus it is possible to learn poorly, incorrectly, or in such a way as to interfere with performance and not improve it. This kind of process has been suggested by Byl and co-workers34 as the underlying cause of focal dystonia. One of the definitions Feldenkrais gave for learning took this process into account: “Learning is the acquisition of the skill to inhibit parasitic action (components of the action unrelated to the intention behind an action but resulting from a secondary intention) and the ability to direct clear motivations as a result of self-knowledge.”31 An adult engaged in learning to walk again after a stroke with a fear-related reluctance to bear weight on the involved limb would be an example of such a secondary intention.

The process of learning proposed by Feldenkrais is one of discovery. The outcome desired is one of increased awareness. Vereijken and Whiting35 have proposed that discovery learning, in which learners are free to explore any range of solutions in learning to perform a task in any way that they want, is as effective as or more effective than any formal approach to motor learning involving controlled schedules of practice or feedback. This process of discovery has the added dimension of allowing learners to focus on the perceptual understanding of the body/task/environment as a component of the learning process. In the Feldenkrais method this discovery and perceptual learning process is explicit.

Our understanding of how experience and learning restructure almost all areas of the CNS is expanding rapidly.36 A large focus of current thinking in rehabilitation is how to translate neuroplasticity concepts into more effective techniques for rehabilitation.37–39 The method developed by Feldenkrais and practiced by people around the world who are trained in this method is clearly explained by these new principles, creating new approaches to rehabilitation.

Approaches to feldenkrais method.

The two approaches to facilitating learning created by Feldenkrais, ATM and FI, are similar in principle and process although they differ in practice. They are essentially two methods for communicating a sensory experience that the client can consider and act on. The first requirement of the process is to create an environment that is comfortable, safe, and conducive to learning, whether the learner is being moved passively or creating the movement experience voluntarily. The second requirement is that the amount of effort associated with making the movements be reduced greatly so that it is possible to make fine discriminations about the effects of force acting on the system from outside, from inside, or both. The goal is to develop a rich understanding of changes throughout the system produced by small perturbations. This understanding becomes the basis for creating new solutions to movement problems as the client progressively approaches functional movements that she or he desires to perform.40

In FI the practitioner will manually introduce small perturbations into the learner’s system after placing the learner into a safe position closely approximating some desired activity to be learned. Here the practitioner is providing the force inputs and the client is asked to attend to the changes created in response to the perturbation. For example, the practitioner might press gently into the bottom of the client’s foot and ask the client to notice where in the body movement and pressure are felt as a result. This will be repeated a number of times and then some other forces or movements will be introduced. The guiding idea for the practitioner might be to build sensory experiences in the body that are associated with a particular movement, such as rolling. This goal is rarely explicitly expressed to the client and is left to emerge in the client’s understanding of the experience: “Oh, now I am rolling,” or “This feels like rolling to me.” Also there is no strict expectation by the practitioner about what specific movement might emerge. Thus it is possible to create novel and unexpected outcomes of how a particular task might be best performed by this particular person at this time. This allows for a process of assessment that is continually evolving as the intervention is unfolding.40

In practice with an individual client, it is common to move back and forth between ATM and FI during the same session. The session is usually focused on the development of understanding and performing a specific function: turning, rolling, standing, stepping, and so on. ATM is a verbal process in which clients perform their own movements; thus a practitioner can work with many individuals simultaneously. At the same time individuals within the learning group are free to respond differently from one another in ways that may be appropriate only for them as individuals.41 Because ATM is under the active control of the client, this method is often a more effective tool in reestablishing voluntary control (Case Study 39-1).

Evidence of effectiveness.

The theory underlying the Feldenkrais method predicts that there should be changes in perception of the body or body image. Although there have not been a lot of studies in this area, there are several that support this prediction. Elgelid42 reported positive changes in body perception, as evaluated by the semantic differentiation scale in a group of four subjects after a series of ATM lessons. Dunn and colleagues43 reported that subjects who had had a unilateral sensory imagery ATM lesson perceived their experimental sides to be longer and lighter and demonstrated increased forward flexion on that side, linking the changes in perception to changes in motor control. Batson and co-workers44 have shown that ability to image movement is improved in people poststroke after a series of ATM lessons, and furthermore that there is a high positive correlation between the Movement Imagery Questionnaire (MIQ) score and improvements in balance assessed by the Berg Balance Scale.

There is not a lot of literature evaluating the efficacy of the Feldenkrais method in general and even less specifically for people with neurological diagnoses, as a result of the complexity of the problems and the multiple system involvement of the individuals. Evidence-based studies on effectiveness are more easily identified. In a review, Stephens and Miller40 divided the literature into four different areas: pain management, postural and motor control, functional mobility, and psychological and quality-of-life impact. Much of the literature is in case report format. A small amount of the literature is controlled study format, with some of that using randomized control groups. The work on pain management suggests that the Feldenkrais method may be especially effective in treating pain that is biomechanical in origin. This concept may be applied to work with pain in patients with neurological diagnoses, especially pain caused by biomechanical malalignment. No research has been done in this area with neurological patients. Hall and colleagues45 found improvements in balance (Berg Balance Scale [BBS]), mobility (Timed Up-and-Go Test [TUG]), functional activity (Frenchay, Short Form 36 [SF-36]), and vitality (SF-36) in a large group of elderly women compared with control subjects as a result of a 16-week ATM intervention. These results have been confirmed by Vrantsidis and colleagues46 and Connors,47 also using ATM with a group of elderly women. In the areas of psychological and quality-of-life impact, Kerr and colleagues48 have shown decrease in state anxiety in subjects who participated in ATM lessons, and Laumer and colleagues,49 working with young women with eating disorders, have demonstrated positive changes in self-concept, self-confidence, and behavior resulting from participation in ATM lessons. Many of these findings are beginning to be reproduced in clinical populations with neurological diagnoses. Most of the studies to date have been done with people with MS. Colleagues are beginning to look at ATM effectiveness in patients after a stroke (cerebrovascular accident [CVA]).

Research

Multiple sclerosis.

The initial study, done in Germany in 1994, looked qualitatively at the effects of a 30-day ATM experience on a group of people with MS. The investigators concluded that ATM improved overall well-being, resulted in greater self-reliance of the participants, and led to better self-acceptance and a more positive self-image.50 After that, Johnson and colleagues51 studied the effects of FI in people with MS. Although they did not find any significant mobility changes, they did report a decrease in perceived stress in the FI compared with the massage controls. Stephens and colleagues41 reported the cases of four individuals who participated in the same ATM classes over a period of 10 weeks. Three of four reported large improvements in their Index of Well-Being score. All subjectively reported improvements in gait. However, there were no measures of gait that consistently improved across the group. Instead, it was found that changes were appropriate to the participant’s individual needs and resulted in a greater sense of control. In a follow-up to this study, using a randomized controlled group design, Stephens and colleagues52 found improvements in postural control and balance confidence measures, along with a strong tendency toward an increase in self-efficacy and decreased falling. It was also found53 that the ATM group had significant improvements in memory of recent events and perception of positive social support. It is interesting to note that they also had a decrease in pain effects.

Cerebrovascular accident.

The original publication in this area is the classic work, The Case of Nora, in which Feldenkrais explained his work in great detail and described improvements in sensation, perception, and mobility of a woman several years after a right-sided CVA.54 More recently, results from pilot studies are just beginning to be reported in patients with diagnoses of CVA. Connors and Grenough55 reported a decrease in spatial neglect as measured by line and star cancellation tests in a patient after a series of ATM lessons. Nair and colleagues56 reported the recovery of upper-extremity function and the return to playing golf in a 68-year-old man after an 8-week program of ATM and FI. This Feldenkrais program was begun only after a 9-month program of traditional rehabilitation had left him with a nonfunctional hand. The Feldenkrais program included mental imagery and bimanual activities. This subject was also studied before, during, and after the Feldenkrais program with functional magnetic resonance imaging. The magnetic resonance imaging analysis showed that there was a return to higher activity in the involved contralateral primary motor cortex with activity of the right hand compared with higher activity in the ipsilateral M1 and SMA that has been shown in other reports of CVA recovery57 before the Feldenkrais sessions began. This finding suggests a return to more normal brain function even after a period of 1 year after the stroke. A small pilot study (three subjects)58 found an average 33% decrease in movement times on the Wolf Motor Function Test. In another pilot with four subjects, Batson59 found significant improvements in Dynamic Gait Index (P = .033, 55% average) and the BBS score (P = .034, 11% average) and a 35% improvement on the Stroke Impact Scale (SIS). A larger study is in progress to further assess these findings.

Other medical diagnoses.

There are some preliminary findings with other neurological diagnoses. Shelhav-Silberbush60 reported improvements in motor, sensory, kinesthetic, perceptual, and learning functions in two case studies of children with cerebral palsy. Shenkman and colleagues61 reported improvements in balance, gait, and functional movement in two people with Parkinson disease as a result of interventions that were based partly on a Feldenkrais approach. Gilman and Yaruss62 have reported significant improvements in several young children who had problems with stuttering. Ofir63 reported improvements in flexibility, mobility, and level of dependence in two young women who had sustained traumatic brain injuries.

Conclusion.

The Feldenkrais method, in its two forms, embodies a process of somatic learning that aims to develop the perceptual capabilities of clients as it underlies the control of movement. Recent literature suggests that predicted results of improved body perception and motor control are supported in work with people with neurological diagnoses. These findings are encouraging and suggest that the Feldenkrais method will make positive contributions to our understanding and methods of rehabilitation. However, we must approach these findings with caution because many are from case studies or pilot studies done with a small number of people. Research continues to substantiate these claims at a higher evidence-based level. Refer to Box 39-1.

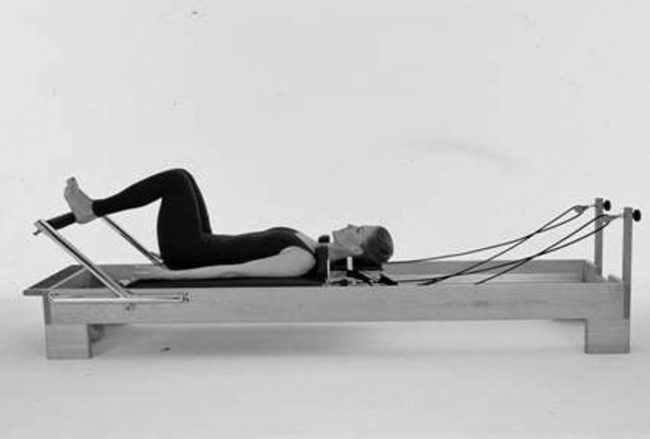

The pilates method

Almost a century later, the Pilates method has gained popularity within the rehabilitation setting because of its assistive nature in restoring functional movement. Rehabilitation practitioners are currently using the method in a variety of fields including orthopedics,64–67 pain management, women’s health,68 neurological rehabilitation, geriatrics, pediatrics,69,70 and even acute care. Most Pilates exercises in the rehabilitation setting are performed on specifically designed apparatus: the Reformer (Figure 39-1), the Cadillac table (Figure 39-2), the Wunda Chair (Figure 39-3), and the Ladder Barrel (Figure 39-4). The apparatus regimen evolved from Joseph Pilates’s original mat work, which was shown to be too difficult for many injured individuals. On the apparatus, springs and orientation to gravity are modified to assist an injured individual to successfully complete movements that would otherwise be difficult or limited. Ultimately, by altering the spring tension or increasing the challenge of gravity, an individual may progress toward functional movement safely, efficiently, and without pain.

The Reformer apparatus used in Pilates.

The Reformer apparatus used in Pilates.

The Cadillac table apparatus used in Pilates.

The Cadillac table apparatus used in Pilates.

The Wunda Chair apparatus used in Pilates.

The Wunda Chair apparatus used in Pilates.

The Ladder Barrel apparatus used in Pilates.

The Ladder Barrel apparatus used in Pilates.Pilates principles.

Joseph Pilates espoused only three guiding principles according to the Pilates Method Alliance: (1) Whole Body Healthy, (2) Whole Body Commitment, and (3) Breath. A number of the first-generation Pilates practitioners known as the Elders expanded Pilates principles to include concentration, control, precision/coordination, isolation/integration, centering, flowing movement, breathing, and routine. Polestar Pilates has modified the eight first-generation principles into six principles that have a greater practicality in the rehabilitation environment and stronger scientific support than the classic principles. The six Polestar Pilates principles include breathing, core control and axial elongation, spine articulation, efficiency of movement, alignment, and movement integration.*

Breathing.

Faulty breath patterns can be associated with complaints of pain and movement dysfunction.71 Pilates movements create an environment where breath facilitates improved air exchange, breath capacity, and posture. During Pilates exercise, breathing is used to facilitate stability and mobility of the spine and extremities. Because of the movement of the rib cage on the thoracic spine, inhalation can promote spinal extension while exhalation can promote spinal flexion. Breath may or may not facilitate movement based on where the breath is occurring. If accessory breath were to occur while attempting spine extension, it would not have a positive movement on the spine articulating into extension. It is then important to realize that the direction of movement in the ribs facilitated by breath determines whether or not breath facilitates movement or not. Likewise, breath may assist with stability of the spine through the coordinated contraction of the diaphragm and the lower abdominal muscles, which both attach to the lumbar spine and pelvis.72,73

Core control and axial elongation.

Core control is the optimal recruitment of the trunk musculature required to perform a given task in relation to the anticipated load. The transversus abdominis, internal abdominal obliques, external abdominal obliques, multifidi, erector spinae, diaphragm, and pelvic floor muscles are key organizational muscles that work together during movement in healthy individuals.74–76 Motor control studies indicate that the coordinated, subthreshold contraction of these local and global stabilization muscles modulate the level of spinal stability required to safely perform activities of daily living.77

Axial elongation is the proper alignment of the head, spine, and pelvis that provides optimal joint spacing during movement. Correct joint spacing avoids working or resting at the end of range, which can place undue stress on the inert and contractile structures of the trunk and extremities.78,79 Through emphasis on axial elongation of the spine and maintaining appropriate joint spacing, soft tissue surrounding the joint can move more freely and the risk of injury can be minimized. Recent discussion has challenged the Pilates approach to core control, attempting to minimize its benefit. As yet, there have been no studies that show that the use of the local stabilizing muscles interferes with or minimizes core stability compared with increasing the intraabdominal pressure by pushing out into the abdominal wall and the hypertrophy of the musculature inside the thoracolumbar fascia. This is more likely to represent rigidity and stability and might serve a population lifting severely heavy weights.

Spine articulation.

Spine articulation is the equal distribution of movement throughout the cervical, thoracic, and lumbar spine. As a motor control principle, spine articulation is where distribution of movement equals distribution of force. It has been suggested that repetitive movement at a hypermobile spinal segment may result in microtrauma or macrotrauma.80–82 Hypermobility is often a result of a lack of movement in a neighboring segment or joint.83 Pilates exercise attempts to facilitate a change in movement strategy during functional tasks. Patients are trained to distribute movement in the spine over a greater number of spinal segments, thereby decreasing potentially harmful forces at the hypermobile segment. The ability to segmentally move the spine decreases unwanted stress and shear of the spinal segments and increases the efficiency and fluidity of movement. The clinical findings of decreased low back pain as a result of Pilates exercise may be due to changed strategy that reduces the stress afforded to the pathological segment.

Efficiency of movement.

Efficiency of movement is the minimization of unnecessary muscle contractions that tend to interfere with healthy movement. The excessive recruitment of antagonist muscles is obstructive and significantly increases the amount of energy required to perform a task.84,85 This principle can be applied to functional movement skills as well as performance skills. Inefficient motor recruitment can often be recognized by the amount of tension or faulty posture in the head, face, neck, and shoulder girdle, in relation to the thoracic spine and trunk.

Alignment and weight bearing of extremities.

Alignment and posture are concepts often incorporated in the field of rehabilitation. The Pilates principle of alignment refers to the most energy-efficient posture (static or dynamic) of the body for a given task. Proper postural organization can significantly decrease energy expenditure during daily activities by improving mechanical advantage.86,87 Faulty alignment in the extremities and the spine can be a source of decreased ROM, loss of joint congruency, early fatigue of muscle groups, or abnormal stresses on inert structures and may potentially cause degeneration and injury.88,89

Pilates provides a closed chain environment that facilitates compression and decompression forces on the axial skeleton and extremities through a full ROM. Adjusting the spring resistance or patient’s orientation to gravity can alter the amount of load. The ability to regulate load on the basis of an individual’s physiological limits, set by age or pathological condition, allows practitioners to more safely and effectively stress the skeletal and soft tissue systems. Theoretically, these forces can help stimulate osteoblastic activity and provide nutrition to a larger surface area of the joint and its surrounding connective tissue.90–92

Movement integration.

Many forms of rehabilitation focus on treating limitations of anatomical structures and neglect the neuromuscular reeducation required to learn to regain the motor control necessary to perform a complex task. Pilates provides a more holistic approach by emphasizing the synthesis of mind (motor control) and body (physical strength and flexibility) to achieve fluid movement. Mobility, control, and coordination of the extremities with the trunk and the trunk with the extremities are examined and trained through motor learning and repetition of practice. In addition to the physical and mental capacity to complete a task, the environment in which a task is performed can greatly affect the success of movement organization.93,94 Pilates provides an environment that can be modified on the basis of a patient’s impairments and limitations, providing a safe, successful, and pain-free movement experience.

Clinical application.

Within the Pilates environment, faulty movement strategies are broken down into components and addressed through task-oriented interventions. By adaptation of the environmental constraints, such as gravity, assistance, and BOS, the degrees of freedom that must be controlled by the nervous system are reduced.95 The successful manipulation of the environment can hasten the functional reeducation process and allow exercises to be safely progressed until the desired outcome is achieved. Pilates practitioners are also trained to be able to modify any exercise so it is pain free for the patient. It has been suggested that successful, pain-free movement, in addition to enhancing physical attributes, helps to alleviate anxiety.96,97 By decreasing anxiety levels and improving self-efficacy, the development of chronic pain and dysfunction related to the injury may be prevented.98–100

One problem often encountered in the rehabilitation setting is flawed movement progression. On a spectrum of movement progression, practitioners often jump from passive movement to resistive movement too quickly. Through facilitation of assistive movement, a pattern can be practiced without irritating the lesion. Assisted movement with the use of springs can allow for a decrease in unwanted muscle activity or guarding that is often associated with pain, weakness, or abnormal tone. As the pattern progresses and symptoms decrease, assistance decreases and dynamic stabilization can be emphasized to challenge the newly acquired mobility or stability in a more functional and gravity-dependent position. Resistive movements are introduced only after adequate dynamic stability of the trunk is demonstrated through controlled movements that prevent excessive loading of the injured tissue. The five environmental conditions in Pilates that are altered to allow a therapist to facilitate motor changes are the following93,101:

Summary.

Pilates is an effective exercise system that works well in conjunction with traditional PT and OT practice. The Pilates-evolved apparatuses allow patients to safely perform exercises that improve strength, flexibility, balance, coordination, and motor control in an environment that can be easily progressed as they advance in their rehabilitation process. In addition, Pilates is thought to address the psychosocial components of an injury that lead to chronic pain or disability by decreasing anxiety and improving self-efficacy.98,99 Early return of functional movement after an injury helps to physically and mentally empower individuals with regard to the demands of life and is crucial in the long-term success of patient outcomes. The Pilates environment is a clinical tool that can be used by practitioners to provide patients with a safe, successful, and pain-free way of restoring function and quality of life.

Tae kwon do

Clinton Robinson, Jr., 9th Degree, Grand Master

Poomsee.

Poomsee is a prearranged dance of defensive and offensive techniques against an imaginary opponent. The practice of poomsee increases the practitioner’s memory, coordination, balance, and body awareness. All poomsee components have predetermined patterns of movements with a proper beginning and ending point that include various stances, along with hand and kicking techniques. The complexity and difficulty of these forms increase as the student progresses. Simple movements and combinations of patterns challenge beginners, and appropriate levels of complex patterns challenge the highest-ranking black belts. Thus all individuals studying TKD are challenged to be in a state of growth and learning.155

Kyorugi.

Kyorugi is actual sparring between two people using both defensive and offensive techniques learned through fundamental TKD practice. Kyorugi can be further broken down into two types. (1) In one-step sparring, practitioners take turns initiating a prearranged attack—one person attacks while the other defends. This allows the practitioners to engage each other without risk of injury to either party. It also allows them to practice proper distancing and execution of the techniques. This develops confidence in the ability to use the techniques properly if the need arises. (2) In free sparring, neither opponent knows what the other is going to do. Although free sparring may appear dangerous to one untrained in TKD, it is a relatively safe activity. Free sparring requires respect for your partner and absolutely controlled motions at all times. It is an exercise in which the aim is for all involved to increase their skill level.156 It develops the practitioner’s quick motor responses, confidence in his or her abilities, and overall awareness as well as a cooperative learning environment.

Although both offensive and defensive techniques are viewed as equally important, all training is begun with blocking techniques to indicate that TKD never allows any initial offensive attack in its technique. Blocking techniques are practiced diligently so that they may function equally as offensive techniques. This way one can defeat an opponent, whether in the classroom or in real life, without either suffering or inflicting serious injuries. This builds self-confidence and replaces a perception of the “role of a victim.”157 Defensive techniques are not only power against power but truly reflect power of the attacker and deflection by the opposition. This deflection can stop the attacker, redirect the power back onto the attacker, or incapacitate the attacker in order for the opposition to get away. The skill in redirecting the force and intent of an attacker is not too different from redirecting a patient’s motor pattern into a direction that would be functional as a motor program. The TKD practitioner and the therapist are working with the pattern of movement presented to them. The intent of the TKD student would be to disempower the attacker, and the intent of the therapist would be to empower the patient.158–160

In TKD training, all students begin in the same place. There is no concern for one’s status in life. The white belt is used to denote the beginning student. With all students beginning at that level, it allows another aspect of training that is critical to all students and individualized. Training encompasses setting and achieving goals or empowering oneself toward excellence and to one’s own quality of life. In TKD, there is a belt ranking system, and the object is to progress through the various levels of proficiency, culminating in attainment of the black belt. Everyone, regardless of social status or physical skill, has the same opportunity to advance in TKD. Students who persevere and obtain a first-degree black belt learn that they have only begun their circle of growth and learning. With additional years of training, students may advance in black belt ranks that should reflect a greater understanding and acceptance of those initial tenets. The circle of growth will always lead to further integration of mind, body, and spirit and an inner peace and balance.161 The balance of mind, body, and spirit is the core of other complementary therapy paradigms and ultimately seems to be an element linked to health and healing.162

Tae kwon do and complementary therapy.154,161,163–167

Although TKD is a martial arts style whose original intent was not to heal a body system condition or to allow one to regain a functional movement activity lost after some acute health care crisis, the concepts and procedures learned, repetitively practiced, and transformed into life behavior have established the foundation for health and healing in individuals. Most students in TKD fall within a health and wellness model of life. Their choice to participate is not based on a bodily system problem as often seen in a PT or OT clinic. These individuals are looking to participate from a wellness perspective and expect that Tae Kwon Do will enhance their balance and their cardiopulmonary and musculoskeletal systems through exercise. Yet many individuals have experienced some aspect of musculoskeletal system problems during their lives. These individuals, as a result of life activities, have forced the CNS to adapt and accommodate to prior bodily system problems such as ligament tears or physical or emotional trauma from bullying in school. These experiences create change whether the deficits are motor, cognitive, or affective.168,169 Similarly, with identified chronic motor limitations that have caused functional activity restriction after a birth trauma, an external head trauma, or an internal insult, TKD can help maintain existing motor function, cognitive integrity, emotional balance, and a feeling of self-worth in the face of a long-term and possibly progressive neurological problem. All these components encourage an individual to participate in life and base advancement not only on the standards of TKD but also the individual goals set by each student.

During warmup, a student stretches and builds up power, using specific movement, balance, timing, concentration, and cardiopulmonary functions that set the stage for the remainder of the class. When doing the forms, the student will need to work on balance, postural tone, the state of the motor generator, synergistic patterns of movement, trajectory, speed, force, directionality, sequencing, reciprocal patterns, and the context within which the movement is being done. Similarly, memory of the specific pattern, movement sequences, and direction of the movements requires concentration. As the student progresses in rank, the specific patterns become more and more complex, increase in number of specific movements, and frequently change from quick movements to slow, controlled patterns. This repetition of practice and increase in difficulty leads to higher skill and cortical representation.170,171 If other students are also practicing in class, then each individual needs to be aware of the total environment to respect the space of all other students. This unique individual experience during a group activity allows for variance during each class and thus should lead to greater motor learning and cortical representation.171,172

When students are learning and practicing either one-step sparring or free sparring, they are not only working on learning combinations of movement patterns and how they interact or conflict with those of their partners, but they are also learning how to control their emotional responses to threatening situations. Little in life is worth hurting another—a basic principle of TKD. During sparring, the potential for injury is directly correlated with the control over the force and direction of movement of each individual. That control can be dramatically affected by emotion (see Chapter 5). Once students learn to control the emotional aspect, their skill and techniques become procedural, which allows their cognitive analytical ability to drive responses (see Chapter 6). The student is then ready to begin study of the mind, body, emotional, and spiritual connections that need to intertwine and become harmonious if the student is to learn the true meaning of TKD. Sparring should be a controlled situation in which injury or damage to another person is never acceptable. Research over the last 10 years has pointed out the danger a student faces during TKD competition. Mistakes both in techniques themselves and in emotional force placed behind the techniques do create a potential danger to students.173–178 Therefore safety gear is required at all TKD competitive events for color belt students. Mouth guards are always required no matter the level of the student. As in other contact sports, injuries do happen, but fortunately most are minor, and a quick recovery the result. During class the instructor is never to spar above the skill level of the student, nor is the student to enter into a sparring match with the intent to show the teacher or another student just how good he or she is. In reality, when a student does take that emotional stance, the motor skills reflect only just how much more that student needs to learn. Feedback from others is a powerful learning tool for students at all levels. It is the teacher’s responsibility to help redirect students’ emotional stances and help to teach that TKD represents control, not lack thereof. Board and brick breaking is the activity in which a student can demonstrate force production as it interlocks with trajectory, speed, and position in space. If any of these perceptual or motor variables are incorrect, the student will not succeed at going through the obstacle. These skills are taught and practiced not to damage or destroy the wood or brick, but rather to learn to go beyond or through the obstacle. Once the specific body part used as a trajectory goes beyond the obstacle, it no longer remains an obstacle and the student feels great satisfaction. In reality, to be successful at these tasks, the hand, elbow, or foot that is used to go through the brick or wood is only an extension of the body. Success is based on the learner’s ability to tie the entire body’s motor response, its rotation, its balance, its trajectory, its force, and its speed into a motor program that will project through one or more obstacles as a knife cuts butter. If the student, emotionally, believes that the obstacle will not break, it will not! The student will stop the movement before completing the task and often empower the wood or brick as a successful obstacle versus empowering herself or himself to overcome that obstacle as if it were not there. This concept is a critical element of TKD. It is also a critical component of any client’s learning of any motor program, turning the program into a functional activity, and improving one’s quality of life and ability to participate in that life’s adventure. If a patient’s CNS is convinced that the movement is not possible, then that individual will fail. Without internal motivation by an individual to accept the possibility of success, acceptance of failure is embraced. This internal environment plays a key role in any individual’s overcoming what he or she perceives as an obstacle in life.179 It is the role of the TKD teacher and the therapist teacher to empower the student to the possibility of success while creating an external environment that will enhance the probability of that success.155,170 To ask TKD students to perform motor skills above their level of competence can lead to injury and the embracing of failure. Failure often stops the motivation to continue to learn. Patients in a therapeutic environment are no different. They need an environment that creates safety, promotes success, and empowers the individual to overcome life obstacles.

Those who respond best to TKD training to maintain motor function are individuals who are motivated to move, enjoy interactions with others, have cognitive integrity, and have some control over their motor system. When instructing a TKD club of individuals who had all had traumatic head injuries, the teacher, a TKD instructor and therapist who had worked for more than 25 years in the area of neurological rehabilitation, found that using therapeutic skills through TKD movement patterns augmented the students’ learning and helped them to regain motor function through guided activities without the students ever realizing there had been any kind of therapeutic intervention. To those students, they were learning and advancing in a martial arts style, were tested and judged according to their development of skills, and felt accomplished as adults participating in an adult activity. Carryover and improvement in balance, postural integrity, reciprocal patterns of movement, and control of trajectory, force, and speed, as well as development of emotional stability and confidence, could be easily identified and evaluated by the use of standard objective measurement tools if so desired. Expected outcomes would be improvement in those areas of motor control just mentioned. As long as the student continued training, improvement would be expected and carryover into other life activities anticipated. These are the principles of neuroplasticity and have meaning both within the predisease or wellness model as seen in TKD37,180 and after acute injury, disease, or insult to the CNS.181–185 Whether sequential movements are taught as new movements as in TKD or require relearning of functional movements taught by physical and occupational therapists, the end result leads to an individual participating in a life activity.

As therapists, we want individuals who have been discharged to continue with movement activities that encourage their participating in life as a whole individual. TKD provides an excellent movement-based activity that leads to physical fitness186–192 and has been studied in relation to changes in vitamin and hormonal levels in elite athletes.193–196 One systematic review studied martial arts training, looking at a variety of martial arts styles including TKD and tai chi. Both styles lead to an increase in health status of participating individuals.197

When considering the elderly population, a group frequently referred to both PT and OT for movement and balance disorders, TKD training has been shown to improve balance, walking abilities, and somatosensory organization in standing.198,199 Owing to immobility, muscle weakness, and decrease in balance in standing, the elderly population certainly presents a fall risk within the community. Falls obviously can lead to hip fractures and months of medical and therapeutic interventions. Looking at a martial art that encourages participants to stretch to their respective limits of stability both with fast and slow movement patterns, a valid question must be asked: “Would TKD be harmful to this population, especially if the participants had osteoporosis?” Two research studies investigated that question and determined that training in martial arts such as TKD can teach fall training, prevent hip fractures, and be safe for individuals with osteoporosis.200,201 Literature has shown that accelerated patterns of the head and pelvis during upright walking can lead to falling in community-dwelling elderly people.202 Individuals with Parkinson disease show evidence of body system problems causing impaired head and trunk control, thus increasing their risk of falling.203 During TKD practice as a beginner or advanced student, individuals learn to use the head and hips in rotational patterns while maintaining an upright posture and moving their upper extremities.204,205 It has also been shown that as students increase their skill with practice and time, they also increase their “neural efficiency,” which increases their reaction time and the ability of their brains to make spatial judgments.206 All these components should help maintain the physical capabilities of an elderly individual while providing a social environment in which to practice.

TKD not only affects the physical and mental capabilities of the learner, but it also has the benefit of changing one’s mood to a more positive feeling.207 This emotional response helps to motivate all students to return to practice and once again regain that positive reaction. This drive becomes deeper and deeper as an individual advances from a white belt to degrees within the black belt ranks.

Over the last decade many research articles have been written that look at one aspect of TKD training, whether it be strength, balance, coordination, motivation, cardiac fitness, emotional self-control, or the effect on the many other bodily systems that interact during a TKD workout. The reader must understand that it is all those elements that make up a TKD student, teacher, or master. In the future, more research will identify this martial art as a potential form of physical exercise for all populations of individuals who have comorbidities after CNS injury (Case Study 39-2). Physicians and therapists should consider recommending this martial art as an exercise activity for individuals who wish to maintain or regain their abilities to participate in life activities.198 Until then, students of all ages will be welcomed into TKD studios and encouraged to reach beyond their perceived potential. The age ranges of TKD students now include the elderly population, with classes focusing on strength, balance, and core work without the need for strenuous sparring or board breaking.208 A TKD instructor will modify each senior’s class experience to allow each individual to reach his or her potential without injury or trauma.

Yoga

Yoga is an ancient Indian mind-body practice that has been around for more than 2000 years.209 It focuses on a combination of meditation, mindfulness, self-exploration, breathing control, and body movement to improve flexibility, focus, balance, and strength. The two types of yoga popular in the United State are Hatha and Iyengar. Hatha involves holding the body in particular postures known as asanas for periods of time while controlling breathing rate and focus.210 Iyengar yoga uses the aid of supports, props, and belts to allow better control to perform the asanas.211,212 Although yoga has been accepted in other countries for centuries, the evolution in the United States has been a recent phenomenon. Research on the effect of yoga in the musculoskeletal areas is promising,212–214 yet research in the neurological population is still in its infancy and in need of larger randomized clinical trials. This section will present a general analysis of the benefits and efficacy of yoga for individuals with a variety of common neurological issues.

Carpal tunnel syndrome.

Physical and occupational therapists treat carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS), an upper-limb neuropathy caused by compression of the median nerve. Symptoms involve numbness, tingling, and pain from repetitive movements that respond to a variety of treatments.215,216 Two studies specifically explored the use of yoga to treat subjects with CTS. A yoga trial with 42 individuals (median age 52, range 24 to 77 years) tested the effectiveness of a yoga regimen on CTS symptoms. Those in the experimental yoga group were given 11 postures designed to stretch and strengthen the upper limbs, along with relaxation techniques, twice a week for 8 weeks at a local geriatric center. A control group was given wrist splints or no treatment at all.217 Significant improvements in grip strength, pain reduction, and Phalen sign were noted. However, no statistically significant change was recorded in sleep improvement, Tinel sign, or median nerve conduction. Participants showed improvements in pain and function 4 weeks later.217 A second study investigated the impact of yoga in patients with osteoarthritis. Twenty-six patients (52 to 79 years) performed 1-hour yoga sessions each week for 8 weeks. Subjects reported significant improvement in joint and hand pain during activity.218 Larger randomized clinical trials could provide definitive evidence for patients with CTS.

Stroke and hemiparesis.

Strokes are the number one cause of adult disability in the United States and Europe, with 4.7 million individuals in the United States living with the sequelae of stroke. Extreme difficulties encountered while performing simple movements result in a sedentary lifestyle in this population. Resultant muscle atrophy further potentiates fall risk.219

A pilot study with four subjects observed the impact of yoga as a treatment for impairments poststroke. Baseline measurements included the BBS, Timed Movement Battery (TMB), and SIS version 2.0. Three of the four participants in this study had statistically improved BBS scores indicating improved balance, improved self-selected speed on the TMB indicating improved ability to perform everyday tasks, and positive changes in quality of life based on the SIS.219

Other factors may have affected the outcome of this pilot study, including differing adherence to the home exercise program with varying participation levels, degree of impairment, and fear of pain, which reduce participation with certain asanas. This preliminary study showed that those who adhered to the program improved more than those who did not follow it as closely. Yoga appears to have some level of positive impact on function in poststroke patients; however, future research is needed to confirm these findings.219

Multiple sclerosis.

Individuals with MS can suffer from virtually any neuropathy, fatigue, ataxia, and chronic or acute pain. Cognitive, digestive, visual, and speech problems may also occur. Although there is no cure for MS, patients have life expectancies similar to those unaffected by the disease, and yoga may be an option to manage the various impairments encountered through the years.220 It is interesting to note that 65% of those diagnosed with MS use some CAM, with yoga being the most popular.221 Perhaps the best study to date was a 6-month study that compared Iyengar yoga and exercise interventions. Participants underwent multiple cognitive assessment tests such as the Stroop Color and Word Test and the Cambridge Neuropsychological Test Automated Battery to test reaction times in performance of certain tasks that are difficult for individuals with MS. These tests measure attention and visual and auditory abilities to determine the impact of cognitive abilities. Alertness, mood, fatigue, and quality of life were also measured using tests such as the Profile of Mood States (POMS), the SF-36, electroencephalography, and physical activities such as a timed walk.220 Of those who completed the study, both the exercise and yoga intervention groups had greater quality of life based on data from self-assessment forms (SF-36), a reported increase in vitality and energy, and a decrease in fatigue.220 This is the first study on the use of yoga for patients with MS, and the findings need to be confirmed using larger randomized controlled trials.220

Epilepsy.

Yoga, as well as other mind-body practices, has shown promise in helping control seizures. One yoga meditation trial reported a 62% decrease in seizure occurrence at 3 months, 86% at 6 months, and 40% of the subjects becoming seizure free.221,222 The patients in this study had hyperventilation-related epilepsy caused by anxiety, so the meditation and controlled breathing exercises along with the asanas may have led to a better understanding of how the subjects could control their diaphragm, resulting in the high success rates. In this study, electroencephalographic data recorded a large shift in frequency from 0 to 8 Hz to 8 to 20 Hz, with an increase in A-band power and a decrease in D-band power. These results showed improvement in control and power of breathing. It is hypothesized that the yogic meditation regulates the limbic system, providing better control over endocrine secretions and lowering the chance of over-firing neurons.222 Another investigation tested the use of yogic meditation for 1 year versus a control of no meditation in patients with drug-resistant epilepsy.223 Data showed significant differences between the experimental and control groups, with the experimental group having significantly lower seizure activity over the observation period.222

A study done in an epilepsy care center in 2006 assessed the efficacy of yoga meditation protocol (YMP) as an adjunctive treatment in patients with drug-resistant chronic epilepsy.224 It was a supervised trial based on the frequency of complex partial seizures, which was assessed after 3, 6, and 12 months. There were 20 patients, who sat in a relaxed position with legs crossed (sukhasana) and focused on deep, slow, controlled breathing (pranayama) for 5 to 7 minutes, followed by silent meditation.224 Patients were instructed to perform YMP daily for 20 minutes in the morning and evening at home and at supervised sessions.224 Individuals with greater than or equal to a 50% reduction in the rate of monthly seizures were classified as responders, whereas patients with less than this percentage in seizure reduction were classified as nonresponders.224 After the first 3 months there was a reduction in the frequency of seizures in all but one patient. Fourteen patients continued the YMP for 6 months or more and were tested again. Of these, six had been seizure free for a 3-month period, and three had been seizure free for 6 months.224 The authors of this study concluded that yoga was a less expensive and an adverse effect–free way to treat patients with drug-resistant forms of epilepsy.

Human immunodeficiency virus.

A pilot study examined the use of a yoga intervention for individuals with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection who experienced pain and anxiety.225 Results indicated a decrease in pain and anxiety symptoms and a reduction in amount of pain medication after an 8-week yoga program.

Another study examined the effect of yoga practice that included breathing, movement, and meditation techniques for 47 participants with HIV disease. Positive changes were noted in mental health on the Mental Health Index (MHI), and general physical health on the Medical Outcomes Study HIV Health Survey (MOS-HIV).226 The Daily Stress Inventory showed a decrease in stress after the yoga program. Improvements in activities of daily living were reported by all yoga participants.

Fear of falling and insufficient balance.

A recent study investigated the use of a 12-week yoga practice for adults over the age of 65 years old with fear of falling and balance problems. Sessions of yoga postures and breathing exercises were completed in sitting and standing.227 Fear of falling was measured using the Illinois Fear of Falling Measure and balance was captured with the BBS before and after the yoga intervention. Results showed a 6% decrease in fear of falling, 4% increase in static balance, and 34% increase in lower-body flexibility.227